{PDF EPUB} the Desperate Hours by Joseph Hayes the Desperate Hours by Joseph Hayes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Functional Music of Gail Kubik: Catalyst for the Concert Hall

The Functional Music of Gail Kubik: Catalyst for the Concert Hall Alfred W. Cochran From the late 1930s through the mid-1960s, three composers for the concert hall profoundly influenced American music and exerted a strong influence upon music in the cinema-Virgil Thomson (1896-1989), Aaron Copland (1900-90), and Gail Kubik (1914-84). Each won the Pulitzer prize in music, and two of those awards, Thomson's and Kubik's, were derived from their film scores. 1 Moreover, both Thomson and Copland earned Academy Awards for their film work. 2 All three men drew concert works from their film scores, but only Kubik used functional music as a significant progenitor for other pieces destined for the concert hall. An examination of his oeuvre shows an affinity for such transformations. More common, perhaps, was the practice of composers using ideas derived from previously composed works when writing a film score. In Kubik's case, the opposite was true; his work for radio, films, and television provided the impetus for a significant amount of his nonfunctional music, including chamber pieces and orchestral works of large and small dimension. This earned well-deserved praise, including that of Nadia Boulanger, who was Kubik's teacher and steadfast friend. Kubik was a prodigy-the youngest person to earn a full scholarship to the Eastman School of Music, its youngest graduate (completing requirements in both violin and composition), a college teacher at nineteen, the MacDowell Colony'S youngest Fellow, and the youngest student admitted to Harvard University'S doctoral program in music. In 1940, he left the faculty of Teachers College, Columbia University and became staff composer and music program advisor for NBC. -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Funny Games and the History of Hostage Noir

ANN NO STOCKS SAVAGE NO SPORTS TRIBUTE ™ ALL NOIR www.noircity.com www.filmnoirfoundation.org VOL. 4 NO. 1 CCCC**** A PUBLICATION OF THE FILM NOIR FOUNDATION BIMONTHLY 2 CENTS MARCH / APRIL 2009 BLACK AND WHITE AND READ ALL OVER IN MEMORIAM DAHL, DEADLINES ANN SAVAGE DOMINATE NC7 By Haggai Elitzur Special to the Sentinel n e l or January, San Francisco’s weather was l A . unusually warm and sunny, but the atmos- M d phere was dark and desperate indoors at the i v F a Castro Theatre, as it always is for the NOIR CITY D film festival. On this, the festival’s seventh outing, Eddie Muller and Arlene Dahl onstage at the Castro most of the selections fell into the theme of news- paper noir. tive MGM when Warner Bros. was tardy in re- upping her contract. Arlene Dahl: Down-to-Earth Diva Dahl described meeting a large group of This year’s special guest was the still-beauti- friendly stars, including Gary Cooper, on her very ful redhead Arlene Dahl, whose two 1956 features first day on the Warner Bros. lot. She also offered screened as a double bill. Wicked as They Come some brief details about her two-year involvement By Eddie Muller was a British production featuring Dahl as a social with JFK, which was set up by Joe Kennedy him- Special to the Sentinel climber seducing her way across Europe. Slightly self. It was a spellbinding interview with a great Scarlet, a Technicolor noir filmed by John Alton, star; Dahl made it clear that she loved the huge ANN SAVAGE CHANGED MY LIFE . -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

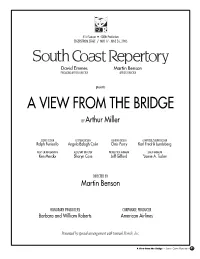

A View from the Bridge

41st Season • 400th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / MAY 17 - JUNE 26, 2005 David Emmes Martin Benson PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR presents A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE BY Arthur Miller SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN COMPOSER/SOUND DESIGN Ralph Funicello Angela Balogh Calin Chris Parry Karl Fredrik Lundeberg FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER Ken Merckx Sharyn Case Jeff Gifford *Jamie A. Tucker DIRECTED BY Martin Benson HONORARY PRODUCERS CORPORATE PRODUCER Barbara and William Roberts American Airlines Presented by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. A View from the Bridge • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Alfieri ....................................................................................... Hal Landon Jr.* Eddie ........................................................................................ Richard Doyle* Louis .............................................................................................. Sal Viscuso* Mike ............................................................................................ Mark Brown* Catherine .................................................................................... Daisy Eagan* Beatrice ................................................................................ Elizabeth Ruscio* Marco .................................................................................... Anthony Cistaro* Rodolpho .......................................................................... -

(XXXVIII:10) Michael Cimino: the DEER HUNTER (1978, 183 Min.) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

April 9, 2019 (XXXVIII:10) Michael Cimino: THE DEER HUNTER (1978, 183 min.) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. DIRECTOR Michael Cimino WRITING Michael Cimino, Deric Washburn, Louis Garfinkle, and Quinn K. Redeker developed the story, and Deric Washburn wrote the screenplay. PRODUCED BY Michael Cimino, Michael Deeley, John Peverall, and Barry Spikings CINEMATOGRAPHY Vilmos Zsigmond MUSIC Stanley Myers EDITING Peter Zinner At the 1979 Academy Awards, the film won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Film Editing, Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and Best Sound, and it was nominated for Oscars for Best Actor in a Leading Role, Best Actress in a Supporting Role, Best Writing, and Best Cinematography. CAST Robert De Niro...Michael John Cazale...Stan John Savage...Steven Christopher Walken...Nick was the first of a “spate of pictures. .articulat[ing] the effect on Meryl Streep...Linda the American psyche of the Vietnam war” (The Guardian). George Dzundza...John Cimino won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Directing and was Chuck Aspegren...Axel nominated for Best Writing for The Deer Hunter. The film was Shirley Stoler...Steven's Mother such an artistic and critical accomplishment that he was given Rutanya Alda...Angela carte blanche from United Artists to make his next film, the Pierre Segui...Julien western Heaven’s Gate* (1980). This decision was a serious Mady Kaplan...Axel's Girl blow to Cimino’s directorial career, and it brought about the Amy Wright... Bridesmaid downfall of United Artists, forcing its sale to MGM in 1981 (The Mary Ann Haenel...Stan's Girl Guardian). -

Cazador Cazado

CAZADOR CAZADO Michael Cimino. El año del dragón, 1985. on estudios en arquitectura y pintura, Mi- brece, sin llegar a eclipsar, los méritos de un en su versión original logró seducir a la crítica, Cchael Cimino (Nueva York, 1943), graduado fi lme clásico. en mucho debido a la elegante fotografía de Vil- de la Universidad de Yale, se inició fi lmando a- Con el estatus que confi ere la distinción de mos Zsigmond que incluye atractivos virados en nuncios publicitarios y posteriormente colaboró obtener el Oscar a mejor película y mejor direc- sepia. en la elaboración del guión de Naves misteriosas tor, Cimino persuadió a la casa productora Uni- Señalado por la industria del cine, Cimino (Silent Running, 1971), del creador de los efectos ted Artist para que le cumplieran todas sus exi- que en cuatro años tocó el cielo con sus manos especiales de 2001: Odisea del espacio (2001: gencias de producción para rodar el sofi sticado y se despeñó en el infi erno del fracaso, se man- A Space Odyssey, 1968), Douglas Trumbull. En western histórico La puerta del cielo (Heaven’s tuvo fi rme en sus convicciones y continuó de 1973 escribió junto a John Milius el guión de Mag- Gate, 1980), cinta subestimada por el gran pú- manera discreta ofreciendo muestras de su ca- num 44 (Magnum Force) segunda parte de la blico y vapuleada por la crítica, que tuvo que ser pacidad en cintas como El año del dragón (Year saga de Harry el sucio (Dirty Harry, 1971). sometida a un recorte obligado de 149 minutos, of the Dragon, 1985), Horas de angustia (Despe- Cimino convence a Clint Estwood para que pero ni aún así fue comercialmente atractiva. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

October 2016 at Bamcinématek

October 2016 at BAMcinématek The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. SEP 29—OCT 6 (8 Days, 9 Films) DESPERATE HOURS: THE FILMS OF MICHAEL CIMINO “In Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, The Deer Hunter and Heaven’s Gate we can see the work of a real American artist: ambitious, passionate, historically engaged – and magnificent.” – Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian Of all the titan-auteurs to emerge during the legendary New Hollywood of the 1970s, none was more audacious and controversial than the late Michael Cimino. In his too few films, Cimino explored American myths, rituals, and masculinity with an unrivaled sense of epic grandeur and an often breathtaking visual style. The series comprises a complete Cimino retrospective—including Heaven’s Gate (1980), The Deer Hunter (1978), Year of the Dragon (1985), The Sunchaser (1996), Desperate Hours (1990), The Sicilian (1987), and his directorial debut, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)—in addition to Silent Running (1972) and Magnum Force (1973), for which he wrote the screenplays. OCT 7—9 (3 Days, 5 Films) NILSSON SCHMILSSON On the 75th anniversary of Harry Nilsson’s birth, BAMcinématek looks back at a selection of the Brooklyn native’s ingenious film compositions Possessed of a sweetly guileless voice and a knack for hummable melodies, offbeat pop genius Harry Nilsson eschewed the trappings of rock stardom to follow his own eccentric vision. Like The Beatles—who famously named Nilsson as their favorite American recording artist and whom he later befriended—their careers included detours into the world of cinema. The series includes Popeye (Altman, 1980), Skidoo (Preminger, 1968), Son of Dracula (Francis, 1975), The Point (Wolf, 1971), and Midnight Cowboy (Schlesinger, 1969). -

IBDB Matching Assignment

MATCHING GAME: Broadway Musicals For each song title, write the letter that corresponds with the Broadway musical it comes from. You can use the Internet Broadway Database (www.ibdb.com) as a resource. The first one has been done for you as an example. Song Title Musical Answer Choices (Musicals) 1. The Song of Purple Summer R A. Annie 2. On My Own B. Anything Goes 3. I Could Have Danced All C. Billy Elliot the Musical Night 4. Popular D. Bye Bye Birdie 5. You Can’t Stop the Beat E. Chicago 6. Luck Be a Lady F. A Chorus Line 7. Seventy Six Trombones G. Guys and Dolls 8. One H. Hairspray 9. All That Jazz I. Jersey Boys 10. La Vie Boheme J. Les Miserables 11. Think of Me K. Mamma Mia! 12. Money, Money, Money L. Mary Poppins 13. Tonight M. The Music Man 14. It’s the Hard Knock Life N. My Fair Lady 15. Can’t Take My Eyes Off of O. Phantom of the Opera You 16. Feed the Birds P. Pirates of Penzance 17. I Get a Kick Out of You Q. Rent 18. Solidarity R. Spring Awakening 19. Put on a Happy Face S. West Side Story 20. I Am the Very Model of a T. Wicked Modern Major General “Best Play” Tony Award Winners 1950-1969 For each play, match the author and the year it won the Tony award for Best Play. You can use the Internet Broadway Database (www.ibdb.com) as a resource. The first one has been done for you. -

Shaw Purnell SAG/AFTRA

SAG/AFTRA AEA Shaw Purnell www.shawpurnell.com imdb.me/shawpurnell.com Representation: Liz Fuller, Citizen Skull Management (323) 302-4242 x129 Neil Kreppel, Commercial Talent Agency, (818)505-1431 Commercial Becca Thomas, Lauren Rosen, CTA, (818) 505-1431 Theatrical TELEVISION: Rebel, ABC Co-star Wendy Stanzler Single Parents, ABC Co-star Natalia Anderson FILM: Rejoice supporting Justin Dearing, AFI Loqueesha supporting Jeremy Saville, The Best Movie The Somnium lead Jingyu Liu, Chapman University I See You supporting Manjari Makijany, AFI DWW Welcome to Willowsbrook lead Merissa Jane Lee, USC Thesis Film In the Privacy of Your Own Home supporting Will Galprin, Galprin Productions INTERNET The Harvey Weinstein Trial: Unfiltered Podcast The Unreported Story Society Rubber Chicken Cards Company Steve Rotblatt THEATER: Last Swallows Elizabeth Kiff Scholl, director Villain Evelyn Hollywood Fringe 2018 Deathtrap Myra Sierra Madre Theater, Sierra Madre, Ca. The Fisherman’s Wife Wife The Blank Theater, Los Angeles, Ca. Death of a Miner Bonnie Jean American Place Theater Off Broadway Never Say Die Liz Classic Theater, Off Broadway The Wake of Jamey Foster Katty Capital Repertory Company, Albany The Sorrows of Stephen Christine Capital Repertory Company, Albany The Dining Room Actress #3 Portland Stage Company, Maine Holiday Julia Portland Stage Company, Maine The Hot l Baltimore Suzy Lexington Conservatory Theater The Philanthropist Celia Lexington Conservatory Theater The Country Wife Ms. Squeamish Lexington Conservatory Theater Summerfolk Varvara People’s Light and Theater, Pa, The Misanthrope Eliante People’s Light and Theater, Pa. The Importance of Being Ernest Gwendolen Barter Theater, Abingdon, Va. The Royal Family Gwen Barter Theater, Abingdon, Va. -

P37 Layout 1

lifestyle MONDAY, JULY 4, 2016 FEATURES ‘Deer Hunter’ director Michael Cimino dead at 77 ichael Cimino, who directed the Oscar- characters played by Robert De Niro and winning Vietnam War film “The Deer Christopher Walken, held prisoner by the MHunter” but then saw his career fade North Vietnamese army, playing Russian with a big-money box office flop, died Saturday roulette against each other. “The Deer Hunter” at the age of 77. Besides his grim, moving tale received nine Oscar nominations and won five, of the Vietnam War, Cimino will be remembered including best picture and best director. At the for the budget-busting failure “Heaven’s Gate” time, the Times review called it “a big, awk- released not long thereafter in the 1980s. ward, crazily ambitious, sometimes breathtak- Cimino’s death, first reported by Cannes film ing motion picture that comes as close to festival director Thierry Fremaux and the New being a popular epic as any movie about this York Times, was confirmed by Lt. B. Kim of the country since ‘The Godfather.’” In a statement Los Angeles County coroner’s office. Saturday De Niro said, “Our work together is Kim told AFP that Cimino was found dead something I will always remember. He will be in his Beverly Hills home and that the cause of death is pending. The Times quoted the direc- In this Feb 22, 1979 file photo, tor’s friend and former lawyer Eric Weissmann American movie director Michael as saying Cimino’s body was found at his Cimino listens during a press confer- home after friends were unable to reach him ence in Berlin.