How the Pandemic Has Reshaped the Global Order.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chinese Civil War (1927–37 and 1946–49)

13 CIVIL WAR CASE STUDY 2: THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR (1927–37 AND 1946–49) As you read this chapter you need to focus on the following essay questions: • Analyze the causes of the Chinese Civil War. • To what extent was the communist victory in China due to the use of guerrilla warfare? • In what ways was the Chinese Civil War a revolutionary war? For the first half of the 20th century, China faced political chaos. Following a revolution in 1911, which overthrew the Manchu dynasty, the new Republic failed to take hold and China continued to be exploited by foreign powers, lacking any strong central government. The Chinese Civil War was an attempt by two ideologically opposed forces – the nationalists and the communists – to see who would ultimately be able to restore order and regain central control over China. The struggle between these two forces, which officially started in 1927, was interrupted by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, but started again in 1946 once the war with Japan was over. The results of this war were to have a major effect not just on China itself, but also on the international stage. Mao Zedong, the communist Timeline of events – 1911–27 victor of the Chinese Civil War. 1911 Double Tenth Revolution and establishment of the Chinese Republic 1912 Dr Sun Yixian becomes Provisional President of the Republic. Guomindang (GMD) formed and wins majority in parliament. Sun resigns and Yuan Shikai declared provisional president 1915 Japan’s Twenty-One Demands. Yuan attempts to become Emperor 1916 Yuan dies/warlord era begins 1917 Sun attempts to set up republic in Guangzhou. -

Brazilian Images of the United States, 1861-1898: a Working Version of Modernity?

Brazilian images of the United States, 1861-1898: A working version of modernity? Natalia Bas University College London PhD thesis I, Natalia Bas, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Abstract For most of the nineteenth-century, the Brazilian liberal elites found in the ‘modernity’ of the European Enlightenment all that they considered best at the time. Britain and France, in particular, provided them with the paradigms of a modern civilisation. This thesis, however, challenges and complements this view by demonstrating that as early as the 1860s the United States began to emerge as a new model of civilisation in the Brazilian debate about modernisation. The general picture portrayed by the historiography of nineteenth-century Brazil is still today inclined to overlook the meaningful place that U.S. society had from as early as the 1860s in the Brazilian imagination regarding the concept of a modern society. This thesis shows how the images of the United States were a pivotal source of political and cultural inspiration for the political and intellectual elites of the second half of the nineteenth century concerned with the modernisation of Brazil. Drawing primarily on parliamentary debates, newspaper articles, diplomatic correspondence, books, student journals and textual and pictorial advertisements in newspapers, this dissertation analyses four different dimensions of the Brazilian representations of the United States. They are: the abolition of slavery, political and civil freedoms, democratic access to scientific and applied education, and democratic access to goods of consumption. -

Queimadas No Pantanal Batem Recorde

nº 158 5/10/2020 a 26/10/2020 TOS DA L RA EIT ET U R R A • L P I O I M Ê R P C A T E G O R I A M Í D A I Eleições 2020 Começa a campanha para os candidatos a prefeito e vereador • Pág. 3 Covid-19 na Europa Aumento de casos no continente leva a novas medidas de restrição • Pág. 4 Repórter mirim Entrevista com uma voluntária nos testes da vacina contra o novo coronavírus • Pág. 10 Ponte sobre rio seco no Pantanal, em área atingida pelas queimadas em Poconé, Mato Grosso, em 26 de setembro Queimadas no Pantanal batem recorde Confira as últimas notícias sobre os incêndios na região e em outros pontos do Brasil e depoimentos de quem atua para diminuir os impactos do fogo • Págs. 6 e 7 Crédito: Buda Mendes/Getty Images Crédito: PARTICIPE DO JOCA. Mande sugestões para: [email protected] e confira nosso portal: www.jornaljoca.com.br. BRASIL Confira as raças mais PoPulares De CaChorros e gatos no site Do JoCa: JornalJoCa.Com.br. 53% das casas brasileiras têm ao EM PAUTA menos um animal de estimação, Estudantes organizam homenagens pelo aponta pesquisa Dia dos Professores Por Helena Rinaldi o Brasil, mais da meta- r aça Dos CaChorros de das residências têm Dos DomiCílios Com o Dia Dos Professores che- Nao menos um bicho de brasileiros gando, em 15 de outubro, alunos de di- estimação (cão, gato ou outros), versas escolas estão se organizando segundo pesquisa divulgada em 5% para fazer homenagens, mesmo a dis- 17 de setembro pela Comissão tância. -

2011 Annual Report New England Electric Railway Historical Society Seashore Trolley Museum the National Collection of American S

New England Electric Railway Historical Society Seashore Trolley Museum 2011 Annual Report The National Collection of American Streetcars New England Electric Railway Historical Society Founded in 1939 by Theodore F. Santarelli de Brasch About the Society The New England Electric Railway Historical Society is a nonprofit educational organization which owns and operates the Seashore Trolley Museum in Kennebunkport, Maine and the National Streetcar Museum at Lowell. The Seashore Trolley Museum is the oldest and largest in the world dedicated to the preservation and operation of urban and interurban transit vehicles from the United States and abroad. It has a large volunteer membership and small full-time staff devoted to preserving and restoring the collection, conducting educational programs, and interpreting and exhibiting the collection for the public. Donations are tax deductible under chapter 501(c)3 of the Internal Revenue Service code. Front Cover Upper: A group of students from Thornton Academy in Saco volunteered during Pumpkin Patch. Here they are monitoring the “patch” that had been moved inside Riverside Carhouse due to soggy conditions outside. Pumpkins are “growing” on the step of Sydney, Australia tram No. 1700. PM Lower: Washington DC PCC car No. 1304 was dedicated in 2011 after a largely volunteer restoration that stretched over a number of years. The car operated under its own power in streetcar configuration on May 25, almost exactly 50 years since it left Washington for General Electric’s plant in Erie, PA where it was used for some years to test automated control systems for future generations of rapid transit cars. JS Contents Letter to Members 1 2011 Annual Report Library Report 5 EDITOR PHOTOGRAPHS Conservation Report 6 James D. -

October Term, 1950 Statistics

: : OCTOBER TERM, 1950 STATISTICS Miscel- C\t\ (Tin o 1 X O tjdil laneous Number of cases on dockets _ 13 783 539 1,335 Cases disposed of _ _ 5 687 524 1, 216 Remaining on dockets 8 96 15 119 Cases disposed of—Appellate Docket By written opinions 114 By per curiam opinions 74 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merit cases) 4 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 495 Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket By written opinions 0 By per curiam opinions 3 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 386 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 121 By transfer to Appellate Docket 14 Number of written opinions 91 Number of petitions for certiorari granted 106 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or post- poned 28 Number of admissions to bar (including 531 at Special Term) _ 1, 339 REFERENCE INDEX Page Murphy, J., resolutions of the bar presented 140 Kutledge, J., resolutions of the bar presented 175 Special term held September 20th, during meeting of American Bar Association, as a convenience to attorneys desiring to avail themselves of opportunity to be admitted 1 Conference room sessions 69, 134, 196 Attorney—Motion for a member of the English Bar to partici- pate in oral argument, pro hac vice, granted. (He did not appear.) Motion to postpone argument denied. An indi- vidual statement was filed by one of the Justices (336) . See 340 U. S. 887 72 Attorney—Withdrawal of membership (John Locke Green) __ 236 908025—51 73 : II reference index—continued Page Disbarment—In the matter of Lewis E. -

Projeto Mi Casa, Tu Casa • Minha Casa, Sua Casa

nº 174 9/8/2021 a 23/8/2021 TOS DA L RA EIT ET U R R A • L P I O I M Ê R P C A T E G O R I A M Í D A I Onda de frio Entenda por que as temperaturas foram tão baixas em algumas regiões brasileiras • P á g . 3 A pandemia e a variante delta Órgão dos Estados Unidos alerta para a capacidade de transmissão desta mutação do novo coronavírus • Pág. 4 Jovem venezuelana O Brasil na com uma das obras Tóquio 2020 doadas por crianças País termina e adolescentes de todo Olimpíada na melhor o Brasil posição na história de sua participação nos Jogos • Pág. 11 Projeto Mi Casa, Tu Casa • Minha Casa, Sua Casa inaugura primeiras bibliotecas Dois abrigos para venezuelanos em Boa Vista, Roraima, receberam mais de 6 mil livros • Págs. 6 e 7 ACNUR_Camila Crédito: PARTICIPE DO JOCA. Mande sugestões para: [email protected] e confira nosso portal: www.jornaljoca.com.br. BRASIL raio X doS animaiS de eStimação adquiridoS na pandemia EM PAUTA primeiro pet 23% dos entrevistados adquiriram A vida com o primeiro cão ou gato durante a os pets em pandemia. Desse total: quarentena Estudo mostra adquiriram 38% Somente cãeS Por Helena Rinaldi que pandemia Crédito: Getty Images/Bloomberg Creative Photos levou donos de animais adquiriram Se para oS humanoS a pan- 7% cãeS e gatoS demia do novo coronavírus dimi- de estimação a passar nuiu a interação com outras pes- mais tempo com eles adquiriram soas, para os pets a realidade foi Somente bem diferente: eles passaram a 55% gatoS conviver com seus donos quase o Brasil, 73% dos continuar próximos de o tempo todo. -

The Future of Transpacific Services – United’S Longest Route Gives a Taste of Things to Come Contents

connecting the world of travel The future of transpacific services – United’s longest route gives a taste of things to come Contents United’s longest route gives a taste of things to come 3 US west coast to Asia today 3 The Singapore market – can it work for United? 7 Transpacific manoeuvres – where next? 8 2 © 2016 OAG Aviation Worldwide Limited. All rights reserved United’s longest route gives a taste of things to come With the news at the end of January 2016 that United Airlines plans to operate non-stop flights from San Francisco to Singapore from June, subject to government approval, and using a 252-seat B787-900 aircraft, we consider the wider west coast US-to-Asia market and the implications for transit points in Asia and for other carriers in the market. US west coast to Asia today Based on the first week in March, there are just over 142,000 weekly seats between the six primary airports on the West Coast of the US – Los Angeles (LAX), San Francisco (SFO), San Jose (SJC), San Diego (SAN), Portland (PDX) and Seattle (SEA) - and Asia. Half of all capacity from these airports is on aircraft operated out of LAX with much of the remaining capacity operating from SFO. Asian carriers operate more than two seats for every one operated by an American airline with the split of seats 71% to 29% between Asian and American airlines. WEST COAST US – ASIA CAPACITY Source: schedules analyser LAX SFO SEA SJC SAN US Carriers Asian Carriers PDX 0 20,000 40,000 60,000 80,000 Departing seats per week 3 The future of transpacific services WEST COAST US – ASIA WEEKLY SEATS 1% 1% 1% Source: schedules analyser 10% LAX SFO SEA SJC 50% PDX SAN 37% WEST COAST US – ASIA CAPACITY BY CARRIER Source: schedules analyser United Eva Air Delta Cathay Pacific Korean Airlines Asiana Airlines Air China All Nippon China Airlines Singapore Airlines China Southern Japan Airlines LAX China Eastern PDX Philippine Airlines SAN SEA American SFO Hainan Airlines SJC Air India 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 Departing seats per week 4 © 2016 OAG Aviation Worldwide Limited. -

“Open Veins of Latin America” by Eduardo Galeano

OPEN VEINS OF LATIN AMERICA 1 also by EDUARDO GALEANO Days and Nights of Love and War Memory of Fire: Volume I, Genesis Volume II, Faces and Masks Volume III, Century of the Wind The Book of Embraces 2 Eduardo Galeano OPEN VEINS of LATIN AMERICA FIVE CENTURIES OF THE PILLAGE 0F A CONTINENT Translated by Cedric Belfrage 25TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION FOREWARD by Isabel Allende LATIN AMERICA BUREAU London 3 Copyright © 1973,1997 by Monthly Review Press All Rights Reserved Originally published as Las venas abiertas de America Latina by Siglo XXI Editores, Mexico, copyright © 1971 by Siglo XXI Editores Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publishing Data Galeano, Eduardo H., 1940- [Venas abiertas de America Latina, English] Open veins of Latin America : five centuries or the pillage of a continent / Eduardo Galeano ; translated by Cedric Belfrage. — 25th anniversary ed. / foreword by Isabel Allende. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-85345-991-6 (pbk.:alk.paper).— ISBN 0-85345-990-8 (cloth) 1. Latin America— Economic conditions. 1. Title. HC125.G25313 1997 330.98— dc21 97-44750 CIP Monthly Review Press 122 West 27th Street New York, NY 10001 Manufactured in the United States of America 4 “We have maintained a silence closely resembling stupidity”. --From the Revolutionary Proclamation of the Junta Tuitiva, La Paz, July 16, 1809 5 Contents FOREWORD BY ISABEL ALLENDE ..........................................................IX FROM IN DEFENSE OF THE WORD ........................................................XIV ACKNOWLEDGEMENT… … ..........................................................................X INTRODUCTION: 120 MILLION CHILDRENIN THE EYE OF THE HURRICANE .....................................................… ...........1 PART I: MANKIND'S POVERTY AS A CONSEQUENCE OF THE WEALTH OF THE LAND 1. -

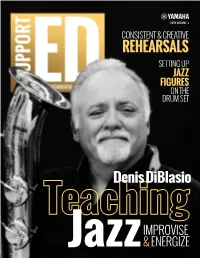

Rehearsals Setting up Jazz Figures on the Drum Set

2019 VOLUME 3 CONSISTENT & CREATIVE REHEARSALS SETTING UP JAZZ FIGURES ON THE DRUM SET Denis DiBlasio IMPROVISE Jazz & ENERGIZE EDITOR’S NOTE SupportED 2019 Volume 3 Young, Talented and Full of Promise PHO une is one of my favorite times of T O Jthe year because it’s when we host BY 4 Navigating Troubled Waters JO the Yamaha Young Performing Artists LESC What are the moral and legal obligations of music educators when (YYPA) Celebration at the Music for H PHO dealing with distressed students? All Summer Symposium at Ball State T O University in Muncie, Indiana. This year’s GRAP YYPA winners were among the most H 6 The Magic of Rehearsal Management Y Capture your students’ attention by creating consistent inspiring and promising artists we have classroom routines as well as applying some sparks of ingenuity. ever worked with. They were humble, open-minded and rose to the occasion in every professional workshop, rehearsal 9 The Inside Scoop: J. Dash and especially during their performances Rapper, songwriter, producer and multi-instrumentalist in front of a cheering crowd of almost his third year at Rutgers University and won it the most. This act takes humility and J. Dash has a genuine passion and commitment to help young 2,000 music students and teachers at the first place in the ITF solo jazz competition. a deep sense of caring and commitment people realize success through the arts. symposium. The talent, enthusiasm and All three are brilliant trombone players, for what is best for the student. camaraderie showcased at the Summer and all three won the YYPA title early in Have you ever had an especially gifted Symposium were remarkable! their careers. -

Hibridizando As Aulas De Língua Inglesa Com O Whatsapp

Bruno Cesar Vieira Maria Edite Resende Vieira HIBRIDIZANDO AS AULAS DE LÍNGUA INGLESA COM O WHATSAPP Caderno com sugestões para atividades de compreensão e produção oral mediadas por tecnologias digitais HIBRIDIZANDO AS AULAS DE LÍNGUA INGLESA COM O WHATSAPP Bruno Cesar Vieira Maria Edite Resende Vieira HIBRIDIZANDO AS AULAS DE LÍNGUA INGLESA COM O WHATSAPP 1ª Edição Rio de Janeiro, 2020 COLÉGIO PEDRO II PRÓ-REITORIA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO, PESQUISA, EXTENSÃO E CULTURA BIBLIOTECA PROFESSORA SILVIA BECHER CATALOGAÇÃO NA FONTE M332 Maria, Bruno Cesar Vieira Hibridizando as aulas de língua inglesa com o Whatsapp: Caderno com sugestões para atividades de compreensão e produção oral mediadas por tecnologias digitais / Bruno Cesar Vieira Maria; Edite Resende Vieira. 1.ed. – Rio de .Janeiro, 2020. 56 f. Bibliografia: p. 51-55. ISBN: 978-65-5930-095-2. 1. Língua inglesa – Estudo e ensino. 2. Língua inglesa (Ensino fundamental). 3. Proficiência oral. 4. WhatsApp (Aplicativo de mensagens) I. Viera, Edite Resende. II. Colégio Pedro II. III. Título. CDD: 428 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Bibliotecária Simone Alves – CRB7 5692. RESUMO O ensino da oralidade constitui um grande desafio para os professores de língua inglesa da rede pública de ensino em função das dificuldades enfrentadas nesse setor. Atualmente, porém, a Internet, à qual tem sido acessada especialmente por meio de dispositivos móveis como o celular, tem proporcionado aos aprendizes maior contato com exemplos de uso do idioma. Assim, esta pesquisa se propôs a investigar o desenvolvimento da oralidade com a integração de tecnologias digitais e foi norteada pelo seguinte problema: em que medida o uso do aplicativo WhatsApp pode propiciar o desenvolvimento de habilidades orais nas aulas de língua inglesa? Traçou-se como objetivo geral investigar as contribuições da utilização do WhatsApp para o desenvolvimento de habilidades orais na língua inglesa de uma turma de 9° ano do Ensino Fundamental. -

Inside Spain 22

Inside Spain 23 William Chislett Foreign Policy Spain pulls troops out of Haiti… Spain pulled its 200 troops out of Haiti despite a request by the United Nations to stay there until the country’s stalled electoral process is completed. They were replaced by Uruguayan soldiers. The government said last June it would reconsider its participation in the Brazilian-led 9,000-strong UN mission unless there was substantial progress in the disbursement of pledged funds for Haiti. The western hemisphere’s poorest country has so far received only slightly more than half of the US$1 billion promised after rebels forced President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to flee the country in February 2004. Few analysts believe this is the real reason for the pull out. The Ministry of Defence prefers to participate in NATO operations than in UN peacekeeping operations, according to a senior UN official, and there have been ‘endless quarrels’ between this ministry and the Foreign Ministry (which has been very supportive of maintaining the troops in Haiti). The UN would have liked Spain to stay until after the completion of the electoral cycle (second round of parliamentary and local/municipal elections still to be held). This led Juan Gabriel Valdés, the head of the mission, to visit Madrid in March and Kofi Annan, the UN Secretary General, to send a letter to José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the Prime Minister. Although the Spanish withdrawal created operational problems and is one of the factors for putting back the parliamentary elections from April 12 to 21, the UN is grateful to Madrid as it is the only EU contributor to the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) and thus a tangible expression of European concern for Haiti. -

Francesco De Pinedo's 1925 Flight from Europe to Australia

Race, technological modernity, and the Italo-Australian condition: Francesco De Pinedo's 1925 flight from Europe to Australia Author Lee, Christopher, Kennedy, Claire Published 2020 Journal Title Modern Italy Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/mit.2020.17 Copyright Statement © 2020 Cambridge University Press. This is the author-manuscript version of this paper. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/397355 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Race, technological modernity, and the Italo-Australian condition: Francesco De Pinedo's 1925 flight from Europe to Australia Christopher Lee (Griffith University) and Claire Kennedy (Griffith University) Abstract Writing about fascism and aviation has stressed the role technology played in Mussolini's ambitions to cultivate fascist ideals in Italy and amongst the Italian diaspora. In this article we examine Francesco De Pinedo's account of the Australian section of his record-breaking 1925 flight from Rome to Tokyo. Our analysis of De Pinedo's reception as a modern Italian in a British Australia, and his response to that reception, suggests that this Italian aviator was relatively unconcerned with promoting fascist greatness in Australia. De Pinedo was interested in Australian claims to the forms of modernity he had witnessed in the United States and which the fascists were attempting to incorporate into a new vision of Italian destiny. Flight provided him with a geographical imagination which understood modernity as an international exchange of progressive peoples.