1 Qing Military Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manchus: a Horse of a Different Color

History in the Making Volume 8 Article 7 January 2015 Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color Hannah Knight CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Knight, Hannah (2015) "Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color," History in the Making: Vol. 8 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol8/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Manchus: A Horse of a Different Color by Hannah Knight Abstract: The question of identity has been one of the biggest questions addressed to humanity. Whether in terms of a country, a group or an individual, the exact definition is almost as difficult to answer as to what constitutes a group. The Manchus, an ethnic group in China, also faced this dilemma. It was an issue that lasted throughout their entire time as rulers of the Qing Dynasty (1644- 1911) and thereafter. Though the guidelines and group characteristics changed throughout that period one aspect remained clear: they did not sinicize with the Chinese Culture. At the beginning of their rule, the Manchus implemented changes that would transform the appearance of China, bringing it closer to the identity that the world recognizes today. In the course of examining three time periods, 1644, 1911, and the 1930’s, this paper looks at the significant events of the period, the changing aspects, and the Manchus and the Qing Imperial Court’s relations with their greater Han Chinese subjects. -

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: the Great Qing and the Maritime World

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultüt der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Chung-yam PO Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kurtz Datum: 28 June 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgments 3 Emperors of the Qing Dynasty 5 Map of China Coast 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 43 Chapter 2 Modeling the Sea Space 62 Chapter 3 The Dragon Navy 109 Chapter 4 Maritime Customs Office 160 Chapter 5 Writing the Waves 210 Conclusion 247 Glossary 255 Bibliography 257 1 Abstract Most previous scholarship has asserted that the Qing Empire neglected the sea and underestimated the worldwide rise of Western powers in the long eighteenth century. By the time the British crushed the Chinese navy in the so-called Opium Wars, the country and its government were in a state of shock and incapable of quickly catching-up with Western Europe. In contrast with such a narrative, this dissertation shows that the Great Qing was in fact far more aware of global trends than has been commonly assumed. Against the backdrop of the long eighteenth century, the author explores the fundamental historical notions of the Chinese maritime world as a conceptual divide between an inner and an outer sea, whereby administrators, merchants, and intellectuals paid close and intense attention to coastal seawaters. Drawing on archival sources from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the West, the author argues that the connection between the Great Qing and the maritime world was complex and sophisticated. -

Did the Imperially Commissioned Manchu Rites for Sacrifices to The

religions Article Did the Imperially Commissioned Manchu Rites for Sacrifices to the Spirits and to Heaven Standardize Manchu Shamanism? Xiaoli Jiang Department of History and Culture, Jilin Normal University, Siping 136000, China; [email protected] Received: 26 October 2018; Accepted: 4 December 2018; Published: 5 December 2018 Abstract: The Imperially Commissioned Manchu Rites for Sacrifices to the Spirits and to Heaven (Manzhou jishen jitian dianli), the only canon on shamanism compiled under the auspices of the Qing dynasty, has attracted considerable attention from a number of scholars. One view that is held by a vast majority of these scholars is that the promulgation of the Manchu Rites by the Qing court helped standardize shamanic rituals, which resulted in a decline of wild ritual practiced then and brought about a similarity of domestic rituals. However, an in-depth analysis of the textual context of the Manchu Rites, as well as a close inspection of its various editions reveal that the Qing court had no intention to formalize shamanism and did not enforce the Manchu Rites nationwide. In fact, the decline of the Manchu wild ritual can be traced to the preconquest period, while the domestic ritual had been formed before the Manchu Rites was prepared and were not unified even at the end of the Qing dynasty. With regard to the ritual differences among the various Manchu clans, the Qing rulers took a more benign view and it was unnecessary to standardize them. The incorporation of the Chinese version of the Manchu Rites into Siku quanshu demonstrates the Qing court’s struggles to promote its cultural status and legitimize its rule of China. -

Sample File Miquelet Ferguson Mfg: Greek 1790 to 1850 Mfg: English 1776 to 1778 .65 Cal .60 Cal Muzzle Velocity: 800 Fps Weight: 13 Lb

Recoil Action: Firearm action that uses the force of the recoil to provide energy to cycle the action. Roller-delayed Blowback: A type of fi rearm action where rollers on the sides of the bolt are driven inward against a tapered bolt carrier extension. This forces the bolt carrier rearward at a higher velocity and delays movement of the bolt head. Rolling Block Action: A fi rearm action where the breech is seeled with a specially shaped breechblock able to rotate on a pin. The breechblock is locked in place by the hammer preventing the cartridge from moving backwards when fi red. Cocking the weapon allows the breechblock to be rotated to reload the weapon. Short Recoil Action: Action where the barrel and slide recoil together a short distance before they unlock and separate. The barrel stops quickly, and the slide continues rearward, compressing the recoil spring and performing the automated extraction and feeding process. During the last portion of its forward travel, the slide locks into the barrel and pushes the barrel back into battery. Slide Action: A fi rearm action where the handgrip is moved back and forth along the barrel in order to eject a spent cartridge and chamber a new one. This type of action is most common in shotguns and is also used in some rifl e designs. It is also called pump action. Snaphance: A method of fi ring a gun that uses a fl int set in the hammer that when the trigger is pulled causes the fl int to strike the frizzen to create a shower of sparks to ignite the priming powder. -

Updates on Chinese Port Information During COVID-19 Outbreak - 10.03.2020

Moir Alistair From: Harris Guy Sent: 12 March 2020 15:40 To: Group - IR Subject: FW: Huatai Info-Updates on Chinese Port Information during COVID-19 outbreak - 10.03.2020 Importance: High trProcessed: Sent From: 北京海事 <[email protected]> Sent: 10 March 2020 13:26 To: Chan Connie <[email protected]> Subject: Huatai Info-Updates on Chinese Port Information during COVID-19 outbreak. - Mar 10th, 2020 Dear Sirs/Madams, With the improvement of the epidemic situation, work resumption is taking place across China except for Hubei province, the hardest-hit region. With the increase of overseas COVID-19 cases, ports are becoming the front line of the battle against the epidemic. Most protective measures implemented by port authorities are still in force and we suggest shipowners to keep on following the notice we made in our previous Huatai Info to avoid any problems. Please note that to date our Huatai offices have come back to normal operating condition. Though some of our staff continues to work from home, they can be reached by email and mobile phone as normal. Besides the daily case handling, we shall keep collecting relevant information on COVID-19 related policy as well as latest port situation to protect Club/Members’ best interests. At the end of this Info we hereby provide the updated port information collected from local parties concerned (port authorities, survey firms, etc.) to help Club/Members make the best arrangement when your good vessel facing any potential claims during calling at Chinese ports. We really appreciate all your thoughtfulness and concern about our situation during Covid-19 epidemic. -

THE JACOB RIFLE and ITS EXPLODING PROJECTILE an Approach to Evaluating Historically Attributed Firearms and a Request for ASAC Help

THE JACOB RIFLE AND ITS EXPLODING PROJECTILE An Approach to Evaluating Historically Attributed Firearms and a Request for ASAC Help By Bob Carlson Figure 1: The Jacob rifle with bayonet, by Swinburn & Son. One of the most intriguing, unusual firearms, perhaps worthy of inclusion in Winant’s “Firearms Curiosa”, is the Jacob rifle! Be- sides having double 24-inch barrels, as well as a single barreled variant, it fired both solid and explosive bullets, designed to blow up mutinous Indian artillery caissons at long range, perhaps up to 1,400 yards (or as some feel, to the 2,000 yards to which its 5-inch- long ladder sight is graduated )! The appearance of a twenty-four- inch double barreled, deeply rifled firearm mounted with a huge bayonet with its 30-inch blade and Scottish-highland type cut-out basket guard, is bizarre and incongruous indeed (Figure 1). The “Perfected” Jacob Rifle The final design of this very unusual and innovative English rifle was completed by the quixotic General (then Major) John Ja- cob (Figure 2) in 1857, by the time of the Indian Mutiny to arm Figure 2. Engraving of Brig. General John Jacob by Thomas Lewis his special battalion of native Indian riflemen, the “Jacob Rifles” Atkinson, 1859 (Left). This marble bust resides at Taunton Shrine (eventually the 36th Jacob’s Horse). Englishman John Jacob, like Hall (right). The pedestal reads: Born at Somerset, January 11, 1812, Sir Joseph Whitworth, was renowned as a mathematician and en- he was dauntless, indefatigable, and unselfish, a born General, a gineer as well as a courageous soldier. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Wood, Christopher Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Original Citation Wood, Christopher (2013) Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/19501/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Were the developments in 19th century small -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries. -

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment for the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire

China’s policy towards South Korea: 1961-2017 by Yin Xuan PENG A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire October 2020 1 2 Abstract In the realm of Chinese foreign policy, the majority of scholars and pundits analyze China’s policy towards South Korea from the perspective of China’s rational diplomatic thinking that caters to China’s national interest maximization. However, I argue that China’s diplomacy with South Korea from the late Mao Ze- dong era to the early Xi Jin-ping era should be considered as a combination of the influence of China’s national interest calculation, the Chinese leadership’s diplomatic thinking, the factional struggle among Chinese cadres. The thesis of mine, thereby, attempts to make a contribution to explanation of China’s policy towards South Korea from aspects of Mao’s pursuit of ‘pure’ communism and Deng’s success in the campaign against the Chinese radicals, even though the Sino-South Korean relationship has been viewed as an interest-oriented bilateral diplomacy. China’s new approach towards South Korea emerged from the year of 1961 as Park Chung-hee (1961-1979) became the de facto paramount political leader, as prepared to use developmental policies to promote its modernization programme – the “Miracle on the Han River”, which laid a foundation for a new economic relationship between China and South Korea. Deng Xiao-ping (1978- 1992) did not put forward the “Four Modernization Programme” (“四个现代化” – sige xiandaihua) until the Chinese reformists returned to power, which enabled China to promote secret business dealings with South Korea in the 1980s. -

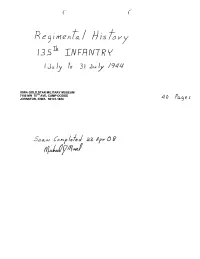

Re 9J Me11 T / )-)Is Tovy

( Re 9 j me 11 t / )-) is to vy 1JSIb. INFANTRt( / Ju I)' to 31 Ju!y /941.1 IOWA GOLD STAR MILITARY MUSEUM TH 7105 NW 70 AVE, CAMP DODGE 4 0 Pc e s JOHNSTON, IOWA 50131-1824 a.:;1 (~ ( R F GI MEN TAL HIS Tan Y MontL of JUL 19H ._". .-.- - ...,. -.': .:;;;:~.~~.:::.;::;.;--:~~•. -.. --.:·::·:~: .. ·:~-= .. ~-:.7:==::·;::·::::~-.-.:-.-.~·.:. M.·.· __ ·· · . ..-'.)'-'.-. .' '.'--".r-' , / SBC'l.'ION IT , r -:T::1rrant Enlisted Dc:. te Officers Officers Nen " /i 1 July 154 5 4007 2 153 5 3998 3 153 5 3991 4 136 5 .3492 ~ 5 135 :J 3366 6 137 5 3324 7 137 5· 3314 8 1.36 5 3287 9 1.37 5 3267 10 136 . 5 3246 11 134- 5 32~ J 12 134 5 3335 13 132 5 3327 JJ 111 t",. 134 5 3292 vJ I,.t- 15 134 5 32<;) ~ 16 135 5 32713 -+ 17 134 5 3208 f 18 128 5 3236 1'---\ ; 19 128 5 3218 20 130 5 3298 1\-'1 21 129 5 3319 , 22 r--, ·12,g 5 3313 ,/ [ 23 128 5 3307 JJ~l 24 127 5 3325 25 126 5 3326 v [ 26 .> 124 5 3332 ~! 27 126 5 33611 28 126 5 3371 ) ! 29 ·.126 5 3379 o ! 30 130 5 3405 l 31 132 5 3420 - lrJ I, - I t r t fti G 1 'A;'1'j.. .J • \ \-\(l ....._.. - -- ~ --.~._-- ... -- --.~.----__.---_... -- ,./ - ., SECTION 1[1- STATION LIST July 1, - July 31, 1944 • 1--------'---------------- 1 July 194.4 135th Inf•. 22;175 2 J'J:l 1944 negtl Hq 161212 Hq Co "161212 AT Co II Cannon Co II Mad Det II 1st Bn It 2nd En It 3rd Bn II I 4 July 1944 t Regtl Hq' 150290 Hq Co J.67212 SaM Co 210230 AT Co 150290 Cannon Co II I-!ed Det 161212 1st En 15029- II 2nd Bn " ;rd Bn II' I 8 July 1944 J SeM-Co 16822(' ,. -

History, Background, Context

42 History, Background, Context The history of the Qing dynasty is of course the history of hundreds upon hundreds of millions of people. The volume, density, and complexity of the information contained in this history--"history" in the sense of the totality of what really happened and why--even if it were available would be beyond the capacity of any single individual to comprehend. Thus what follows is "history" in another sense--a selective recreation of the past in written form--in this case a sketch of basic facts about major episodes and events drawn from secondary sources which hopefully will provide a little historical background and allow the reader to place Pi Xirui and Jingxue lishi within a historical context. While the history of the Qing dynasty proper begins in 1644, history is continuous. The Jurchen (who would later call themselves Manchus), a northeastern tribal people, had fought together with the Chinese against the Japanese in the 1590s when the Japanese invaded Korea. However in 1609, after a decade of increasing military strength, their position towards the Chinese changed, becoming one of antagonism. Nurhaci1 努爾哈赤 (1559-1626), a leader who had united the Jurchen tribes, proclaimed himself to be their chieftain or Khan in 1616 and also proclaimed the 1See: ECCP, p.594-9, for his biography. 43 founding of a new dynasty, the Jin 金 (also Hou Jin 後金 or Later Jin), signifying that it was a continuation of the earlier Jurchen dynasty which ruled from 1115-1234. In 1618, Nurhaci led an army of 10,000 with the intent of invading China.