Occurrence of the House Sparrow in Alaska Daniel D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer Domesticus

46 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 46--47 Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer domesticus NEIL SHELLEY 16 Birdrock Avenue, Mount Martha, Victoria 3934 (Email: [email protected]) Summary This note describes an incidental observation of House Sparrows Passer domesticus foraging for insects trapped within the engine bay of motor vehicles in south-eastern Australia. Introduction The House Sparrow Passer domesticus is commensal with man and its global range has increased significantly recently, closely following human settlement on most continents and many islands (Long 1981, Cramp 1994). It is native to Eurasia and northern Africa (Cramp 1994) and was introduced to Australia in the mid 19th century (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999). It is now common in cities and towns throughout eastern Australia (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999, Barrett et al. 2003), particularly in association with human habitation (Schodde & Tidemann 1997), but is decreasing nationally (Barrett et al. 2003). Observation On 13 January 2003 at c. 1745 h Eastern Summer Time, a small group of House Sparrows was observed foraging in the street outside a restaurant in Port Fairy, on the south-western coast of Victoria (38°23' S, 142°14' E). Several motor vehicles were angle-parked in the street, nose to the kerb, adjacent to the restaurant. The restaurant had a few tables and chairs on the footpath for outside dining. The Sparrows appeared to be foraging only for food scraps, when one of them entered the front of a parked vehicle and emerged shortly after with an insect, which it then consumed. -

An Annotated List of Birds Wintering in the Lhasa River Watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China

FORKTAIL 23 (2007): 1–11 An annotated list of birds wintering in the Lhasa river watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China AARON LANG, MARY ANNE BISHOP and ALEC LE SUEUR The occurrence and distribution of birds in the Lhasa river watershed of Tibet Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China, is not well documented. Here we report on recent observations of birds made during the winter season (November–March). Combining these observations with earlier records shows that at least 115 species occur in the Lhasa river watershed and adjacent Yamzho Yumco lake during the winter. Of these, at least 88 species appear to occur regularly and 29 species are represented by only a few observations. We recorded 18 species not previously noted during winter. Three species noted from Lhasa in the 1940s, Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata, Solitary Snipe Gallinago solitaria and Red-rumped Swallow Hirundo daurica, were not observed during our study. Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis (Vulnerable) and Bar-headed Goose Anser indicus are among the more visible species in the agricultural habitats which dominate the valley floors. There is still a great deal to be learned about the winter birds of the region, as evidenced by the number of apparently new records from the last 15 years. INTRODUCTION limited from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. By the late 1980s the first joint ventures with foreign companies were The Lhasa river watershed in Tibet Autonomous Region, initiated and some of the first foreign non-governmental People’s Republic of China, is an important wintering organisations were allowed into Tibet, enabling our own area for a number of migratory and resident bird species. -

Виктор Гаврилюк (1928–2005) И Его Вклад В Исследование Чукотки Viktor Gavrilyuk (1928–2005) and His Input in the Study of Chukotka

Растительность России. СПб., 2018. Vegetation of Russia. St. Petersburg, 2018. № 34. С. 147–153. N 34. P. 147–153. https://doi.org/10.31111/vegrus/2018.34.147 ИсторИя наукИ Виктор ГаВрилюк (1928–2005) и его вклад в исследоВание Чукотки VIKTOR GAVRILYUK (1928–2005) AND HIS INPUT IN THE STUDY OF CHUKOTKA © О. В. СВистун¹, Г. А. Чорна², т. В. МаМЧур¹, М. И. Парубок¹ O. V. SVYSTUN, G. A. CHORNA, T. V. MAMCHUR, M. I. PARUBOK ¹Уманский национальный университет садоводства. 20300, Украина, Умань, ул. Интернациональная, 1. Uman National University of Horticulture (Uman city, Ukraine) E-mail: [email protected] ²Уманский государственный педагогический университет им. Павла Тычины. 20300, Украина, Умань, ул. Садовая, 2. Uman State Pedagogical University named after Pavlo Tychyna (Uman city, Ukraine) «…Впереди природа — с которой я никогда не расстанусь; впереди леса, поля — дорогие и милые места; впереди — мои любимые цветы; впереди много людей — моих товарищей… …O, Erd, o, Sonne, o, Glück, o, Lust¹!» Из «Дневника записей событий, в жизни моих происхоящих». В. А. Гаврилюк Начало ХХІ столетия ознаменовалось в ботанической науке под- ведением итогов ряда исследований. Современники по достоинству оценивают труды предшественников, с особым почтением отдавая должное тем ученым-натуралистам, которые по крупицам добыва- ли сведения о растительном мире суровых краев (Полежаев, Череш- нев, 2008; Матвеева, 2014; Мамчур и др., 2017). Итоги изучения растительного покрова Крайнего Севера, в том числе и Чукотки, сотрудниками Ботанического института им. В. Л. Комарова РАН были подведены Надеждой Васильевной Мат- веевой (2014). Она поименно вспомнила более 130 человек, кото- рые в той или иной степени связали свою жизнь с Арктикой. Есть в этом списке и имя Виктора Антоновича Гаврилюка, скромного уманского ботаника, впоследствии подготовившего не одно поколе- ние агрономов для ряда регионов бывшего Советского Союза. -

International Studies on Sparrows

1 ISBN 1734-624X INSTITUTE OF BIOTECHNOLOGY & ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION, UNIVERSITY OF ZIELONA GÓRA INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR ECOLOGY WORKING GROUP ON GRANIVOROUS BIRDS – INTECOL INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ON SPARROWS Vol. 30 University of Zielona Góra Zielona Góra 2 Edited by Working Group on Granivorous Birds – INTECOL Editor: Prof. Dr. Jan Pinowski (CES PAS) Co-editors: Prof. Dr. David T. Parkin (Queens Med. Centre, Nottingham), Dr. hab. Leszek Jerzak (University of Zielona Góra), Dr. hab. Piotr Tryjanowski (University of Poznań) Ass. Ed.: M. Sc. Andrzej Haman (CES PAS) Address to Editor: Prof. Dr. Jan Pinowski, ul. Daniłowskiego 1/33, PL 01-833 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected] “International Studies on Sparrows” since 1967 Address: Institute of Biotechnology & Environmental Protection University of Zielona Góra ul. Monte Cassino 21 b, PL 65-561 Zielona Góra e-mail: [email protected] (Financing by the Institute of Biotechnology & Environmental Protection, University of Zielona Góra) 3 CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................. 5 1. Andrei A. Bokotey, Igor M. Gorban – Numbers, distribution, ecology of and the House Sparrow in Lvov (Ukraine) ...................... 7 2. J. Denis Summers-Smith – Changes in the House Sparrow population in Britain ...................................................................... 23 3. Marcin Bocheński – Nesting of the sparrows Passer spp. in the White Stork Ciconia ciconia nests in a stork colony in Kłopot (W Poland) .................................................................... 39 5 PREFACE The Institute of Ecology of the Polish Academy of Science has financed the journal “International Studies on Sparrow”. Unfortunately, publica- tion was liquidated for financial reasons. The Editing Board had prob- lems continuing with the last journal. Thanks to a proposal for editing and financing the “ISS” from the Institute of Biotechnology and Environmental Protection UZ, the journal will now be edited by University of Zielona Góra beginning in 2005. -

House Sparrow

House Sparrow Passer domesticus Description FUN FACTS The House Sparrow is a member of the Old World sparrow family native to most of The House Sparrow is part of the weaver Europe and Asia. This little bird has fol- finch family of birds which is not related lowed humans all over the world and has to North American native sparrows. been introduced to every continent ex- cept Antarctica. In North America, the birds were intentionally introduced to the These birds have been in Alberta for United States from Britain in the 1850’s as about 100 years, making themselves at they were thought to be able to help home in urban environments. with insect control in agricultural crops. Being a hardy and adaptable little bird, the House Sparrow has spread across the continent to become one of North Amer- House Sparrows make untidy nests in ica’s most common birds. However, in many different locales and raise up to many places, the House Sparrow is con- three broods a season. sidered to be an invasive species that competes with, and has contributed to the decline in, certain native bird spe- These birds usually travel, feed, and roost cies. The males have a grey crown and in assertive, noisy, sociable groups but underparts, white cheeks, a black throat maintain wariness around humans. bib and black between the bill and eyes. Females are brown with a streaked back (buff, black and brown). If you find an injured or orphaned wild ani- mal in distress, please contact the Calgary Wildlife Rehabilitation Society hotline at 403- 214-1312 for tips, instructions and advice, or visit the website for more information www.calgarywildlife.org Photo Credit: Lilly Hiebert Contact Us @calgarywildlife 11555—85th Street NW, Calgary, AB T3R 1J3 [email protected] @calgarywildlife 403-214-1312 calgarywildlife.org @Calgary_wildlife . -

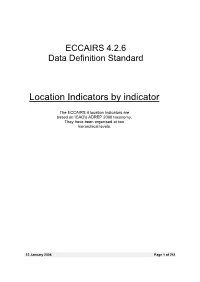

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034 -

Natural Epigenetic Variation Within and Among Six Subspecies of the House Sparrow, Passer Domesticus Sepand Riyahi1,*,‡, Roser Vilatersana2,*, Aaron W

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2017) 220, 4016-4023 doi:10.1242/jeb.169268 RESEARCH ARTICLE Natural epigenetic variation within and among six subspecies of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus Sepand Riyahi1,*,‡, Roser Vilatersana2,*, Aaron W. Schrey3, Hassan Ghorbani Node4,5, Mansour Aliabadian4,5 and Juan Carlos Senar1 ABSTRACT methylation is one of several epigenetic processes (such as histone Epigenetic modifications can respond rapidly to environmental modification and chromatin structure) that can influence an ’ changes and can shape phenotypic variation in accordance with individual s phenotype. Many recent studies show the relevance environmental stimuli. One of the most studied epigenetic marks is of DNA methylation in shaping phenotypic variation within an ’ DNA methylation. In the present study, we used the methylation- individual s lifetime (e.g. Herrera et al., 2012), such as the effect of sensitive amplified polymorphism (MSAP) technique to investigate larval diet on the methylation patterns and phenotype of social the natural variation in DNA methylation within and among insects (Kucharski et al., 2008). subspecies of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus. We focused DNA methylation is a crucial process in natural selection on five subspecies from the Middle East because they show great and evolution because it allows organisms to adapt rapidly to variation in many ecological traits and because this region is the environmental fluctuations by modifying phenotypic traits, either probable origin for the house sparrow’s commensal relationship with via phenotypic plasticity or through developmental flexibility humans. We analysed house sparrows from Spain as an outgroup. (Schlichting and Wund, 2014). -

Download Report

BTO Research Report 384 The London Bird Project Authors Dan Chamberlain, Su Gough, Howard Vaughan, Graham Appleton, Steve Freeman, Mike Toms, Juliet Vickery, David Noble A report to The Bridge House Estates Trust January 2005 © British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 British Trust for Ornithology The London Bird Project BTO Research Report No. 384 Dan Chamberlain, Su Gough, Howard Vaughan, Graham Appleton, Steve Freeman, Mike Toms, Juliet Vickery, David Noble Published in January 2005 by the British Trust for Ornithology The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU, UK Copyright © British Trust for Ornithology 2005 ISBN 1-904870-18-X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables .........................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures........................................................................................................................................5 List of Appendices.................................................................................................................................7 Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................9 -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

Correspondence Seen on 31 January 2020, During the Annual Bird Census of Pong Lake (Ranganathan 2020), and Eight on 16 February 2020 (Sharma 2020)

150 Indian BIRDS VOL. 16 NO. 5 (PUBL. 26 NOVEMBER 2020) photographs [142]. At the same place, 15 Sind Sparrows were Correspondence seen on 31 January 2020, during the Annual Bird Census of Pong Lake (Ranganathan 2020), and eight on 16 February 2020 (Sharma 2020). About one and a half kilometers from this place (31.97°N, 75.89°E), I recorded two males and one female Sind The status of the Sind Sparrow Passer pyrrhonotus, Sparrow, feeding on a village road, on 09 March 2020. When Spanish Sparrow P. hispaniolensis, and Eurasian Tree disturbed they took cover in nearby Lantana sp., scrub [143]. Sparrow P. montanus in Himachal Pradesh On 08 August 2020, Piyush Dogra and I were birding on the Five species of Passer sparrows are found in the Indian opposite side of Shah Nehar Barrage Lake (31.94°N, 75.91°E). Subcontinent. These are House Sparrow Passer domesticus, We saw and photographed three Sind Sparrows, sitting on a wire, Spanish Sparrow P. hispaniolensis, Sind Sparrow P. pyrrhonotus, near the reeds. Russet Sparrow P. cinnamomeus, and Eurasian Tree Sparrow P. montanus (Praveen et al. 2020). All of these, except the Sind Sparrow, have been reported from Himachal Pradesh (Anonymous 1869; Grimmett et al. 2011). The Russet Sparrow and the House Sparrow are common residents (den Besten 2004; Dhadwal 2019). In this note, I describe my records of the Sind Sparrow (first for the state) and Spanish Sparrows from Himachal Pradesh. I also compile other records of these three species from Himachal Pradesh. Sind Sparrow Passer pyrrhonotus On 05 February 2017, I visited Sthana village, near Shah Nehar Barrage, Kangra District, Himachal Pradesh, which lies close to C. -

The Use of Nest-Boxes by Two Species of Sparrows (Passer Domesticus and P

Intern. Stud. Sparrows 2012, 36: 18-29 Andrzej WĘGRZYNOWICZ Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Science Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warsaw e-mail: [email protected] THE USE OF NEST-BOXES BY TWO SPECIES OF SPARROWS (PASSER DOMESTICUS AND P. MONTANUS) WITH OPPOSITE TRENDS OF ABUNDANCE – THE STUDY IN WARSAW ABSTRACT The occupation of nest-boxes by House- and Tree Sparrow in Warsaw was investigated in 2005-2009 and in 2012 . Riparian forests, younger and older parks in downtown, and housing estates were included in the study as 4 types of habitats corresponding to the urbanization gradient of Warsaw . 1035 inspections of nest-boxes suitable for both spe- cies (type A) were carried out during the breeding period and 345 nest-boxes of other types were inspected after the breeding period . In order to determine the importance of nest-boxes for both species on different plots, obtained data were analyzed using Nest-box Importance Coefficient (NIC) . This coefficient describes species-specific rate of occupation of nest-boxes as well as the contribution of the pairs nesting in them . Tree Sparrow occupied a total of 33% of A-type nest-boxes, its densities were positively correlated with the number of nest-boxes, and seasonal differences in occupation rate were low for this species . The NIC and the rate of nest-box occupation for Tree Sparrow decreased along an urbanization gradient . House Sparrow used nest-boxes very rarely, only in older parks and some housing estates . Total rate of nest-box occupation for House Sparrow in studied plots was 4%, and NIC was relatively low . -

Insubation Behavior of the Dead Sea Sparrow

340 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS W. Weller for their helpful suggestions in revising JOHNSGARD,P. A., AND J. KEAR. 1968. A review of the manuscript. parental carrying of young by waterfowl. Living Bird 7:89-102. LITERATURE CITED KEAR, J. 1970. The adaptive radiation of paren- tal care in waterfowl, p. 357-392. In J. H. Crook BERGMAN, R. D., AND D. V. DERKSEN. 1977. Ob- Led.], Social behaviour in birds and mammals__I. servations on Arctic and Red-throated Loons at Academic Press, London. Storkersen Point, Alaska. Arctic 30:41-51. KLOPFER. P. H. 1959. The develonment of sotmA-ALU COLLIAS, N. E., A~TII E. C. COLLIAS. 1956. Some signal preferences in ducks. Wilson Bull. 71: mechanisms of family integration in ducks. Auk 262-266. 73 :378-400. LENSINK, C. J. 1967. Arctic Loon predation on GOTTLIED, G. 1965. Imprinting in relation to pa- ducklings. Murrelet 48:41. rental and species identification by avian neo- nates. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 59:345-356. Department of Biology, Queens’ University, Kingston, H~~HN, E. 0. 1972. Arctic Loon breeding in Al- Ontario K7L 3N6, Canada. Accepted for publication berta. Can. Field-Nat. 86:372. 16 February 1978. Condor, 80:340-343 @ The Cooper Ornithological Society 1978 INCUBATION BEHAVIOR OF THE temperatures (Ta) during the incubation period DEAD SEA SPARROW (April-August) can exceed 45°C at noon, and rela- tive humidity (RH) may fall to less than 10% (Ros- nan 1956, Mendelssohn 1974). Their large, covered Y. YOM-TOV nest is generally built on dead branches of tamarisk A. AR trees, and its exterior is totally exposed to solar radia- AND tion.