Download Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Study Report Re-Accreditation-Third Cycle

SELF-STUDY REPORT RE-ACCREDITATION-THIRD CYCLE Submitted to NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL SHRIMATHI DEVKUNVAR NANALAL BHATT VAISHNAV COLLEGE FOR WOMEN (AUTONOMOUS) Chromepet, Chennai-600044 (Affiliated to University of Madras, Re-accredited with “A” Grade by NAAC ) MARCH 2016 NAAC-Self Study Report (III Cycle) SHRIMATHI DEVKUNVAR NANALAL BHATT VAISHNAV COLLEGE FOR WOMEN (Autonomous) Affiliated to University of Madras NAAC Re-Accreditation – Third Cycle 2011 – 2016 STEERING COMMITTEE Chair Person: Dr.V.Varalakshmi Principal Members: Dr.G Rani, Former Principal (2011 – 2015) & Academic Advisor Dr. C.P.Sumathi, NAAC Coordinator (Aided Stream) Associate Professor & Head, Department of Computer Science Mrs.R.Vijaya, NAAC Coordinator (Aided Stream) Associate Professor & Head, Department of Mathematics Dr.C.S.Vijaya, NAAC Coordinator (Self-Supporting Stream) Assistant Professor & Head i/c, Department of Commerce Dr.C.Victoria Priscilla, NAAC Coordinator (Self-Supporting Stream) Assistant Professor & Head i/c, Department of Computer Science Dr.R.Malathi, IQAC Coordinator (2012 – 2015) Associate Professor & Head i/c, Department of Statistics Dr.G.Vijayasree, IQAC Coordinator (2015 – till date) Assistant Professor, Department of Statistics Mrs.S.Saraswathi, IQAC Member (Aided Stream) Associate Professor, Department of History & Tourism Dr.K.Kanthimathi, IQAC Member (Aided Stream), Assistant Professor, Department of English Shrimathi Devkunvar Nanalal Bhatt Vaishnav College for Women NAAC-Self Study Report (III Cycle) Dr.V.G.Shanthi, IQAC Member (Aided Stream) Assistant Professor, Department of Mathematics Mrs.M.Mahadevi, NAAC Member (Self-Supporting) Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science Mrs.Sudha Senthil, NAAC Member (Self-Supporting) Assistant Professor, Department of Mathematics Mrs.S.Kamakshi, NAAC Member (Self-Supporting) Assistant Professor, Department of B.Com. -

The Way Ahead in Sri Lanka

ch ar F se o e u R n r d e a v t r i e o s n b O ORF Discourse Vol.1 ● No.2 ● November 2006 Published by Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi The Way Ahead in Sri Lanka Summary of an interaction organised by ORF (Chennai) on September 2, 2006 f the stalemated war produced a truce, the stalemated victories in conventional warfare. SLAF is no longer a peace ever since the Sri Lankan Government and ‘ceremonial army’ and its soldiers are ‘children of war’, Ithe Liberation Tigers Tamil Elam signed a cease-fi re and trained in that environment. The LTTE, on the other agreement (CFA) in February 2002 has contributed to the hand, may already be facing cadre-shortage, mainly due revival of violence in the island-nation. The deteriorating to the ‘Karuna rebellion’ in the East and, possibly, because ground situation has been accompanied by repeated calls of large-scale migration of ‘Jaffna Tamils’ ever since the from the Sri Lankan parties for greater Indian involvement ‘ethnic war’ began in the early Eighties. in the peace-making efforts. On the political side, President Mahinda Rajapakse To evaluate the developments, the Chennai Chapter has shown signs of working for a ‘Southern consensus’, of the Observer Research Foundation (ORF-C), which which is a pre-requisite for any peace plan to succeed. is specialising in ‘Sri Lanka Studies, among other issues, The Opposition United National Party (UNP), although it organised a seminar on September 2, 2006 in which rejected his offer for a national government, has offered to participants and discussants focussed on the military cooperate with the `Southern consensus’ initiative. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Jaffna's Media in the Grip of Terror

Fact-finding report by the International Press Freedom Mission to Sri Lanka Jaffna’s media in the grip of terror August 2007 Since fighting resumed in 2006 between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the Tamil-populated Jaffna peninsula has become a nightmare for journalists, human rights activists and the civilian population in general. Murders, kidnappings, threats and censorship have made Jaffna one of the world’s most dangerous places for journalists to work. At least seven media workers, including two journalists, have been killed there since May 2006. One journalist is missing and at least three media outlets have been physically attacked. Dozens of journalists have fled the area or abandoned the profession. None of these incidents has been seriously investigated despite government promises and the existence of suspects. Representatives of Reporters Without Borders and International Media Support visited Jaffna on 20 and 21 June as part of an international press freedom fact-finding mission to Sri Lanka. They met Tamil journalists, military officials, civil society figures and the members of the national Human Rights Commission (HRC). This report is also based on the day-by-day press freedom monitoring done by Reporters Without Borders and other organisations in the international mission. For security reasons, the names of most of the journalists and other people interviewed are not cited here. Since the attack on 2 May last year on the offices of the Jaffna district’s most popular daily paper, Uthayan, local journalists have lived and worked in fear. One paper shut down after its editor was murdered and only three dailies are now published. -

Why Celebrate Chennai?

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/18-20 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/18-20 Publication: 1st & 16th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) INSIDE Short ‘N’ Snappy Museum Theatre gate Mesmerism in Madras Tamil Journalism Thrilling finale www.madrasmusings.com WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI Vol. XXIX No. 8 August 1-15, 2019 Why celebrate Chennai? every three minutes that places by The Editor us ahead of Detroit? When it comes to leather exports did we Our THEN is a sketch by artiste Vijaykumar of old Woodlands here we go again, ask- other to the problems it faces. know that Chennai and Kan- hotel, Westcott Road, where Krishna Rao began the first of his ing everyone to celebrate This is where we ply our trade, pur are forever neck-to-neck T restaurant chain in the 1930s. Our NOW is Saravana Bhavan Chennai, for Madras Week is educate our children, practise for reaching the top slot? And (Courtesy: The Hindu) also equally significant in Chennai’s food just around the corner. The our customs, celebrate our our record in IT is certainly history but whose owner died earlier this month being in the news cynics we are sure, must be individuality and much else. impressive. If all this was not till the end for wrong reasons. already practising their count- Chennai has given us space for enough, our achievements in er chorus beginning with the all this and we must be thankful enrolment for school education usual litany – Chennai was not for that. -

Moving Forward EU-India Relations. the Significance of the Security

Moving Forward EU-India Relations The Significance of the Security Dialogues edited by Nicola Casarini, Stefania Benaglia and Sameer Patil Edizioni Nuova Cultura Output of the project “Moving Forward the EU-India Security Dialogue: Traditional and Emerging Issues” led by the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) in partnership with Gate- way House: Indian Council on Global Relations (GH). The project is part of the EU-India Think Tank Twinning Initiative funded by the European Union. First published 2017 by Edizioni Nuova Cultura for Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Via Angelo Brunetti 9 – I-00186 Rome – Italy www.iai.it and Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations Colaba, Mumbai – 400 005 India Cecil Court, 3rd floor Copyright © 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations (ch. 2-3, 6-7) and Istituto Affari Internazionali (ch. 1, 4-5, 8-9) ISBN: 9788868128531 Cover: by Luca Mozzicarelli Graphic composition: by Luca Mozzicarelli The unauthorized reproduction of this book, even partial, carried out by any means, including photocopying, even for internal or didactic use, is prohibited by copyright. Table of Contents Abstracts .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 15 1. Maritime Security and Freedom of Navigation from the South China Sea and Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: -

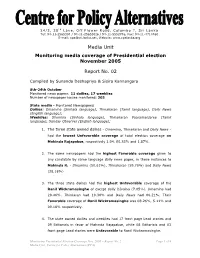

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

Media Freedom in Post War Sri Lanka and Its Impact on the Reconciliation Process

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford MEDIA FREEDOM IN POST WAR SRI LANKA AND ITS IMPACT ON THE RECONCILIATION PROCESS By Swaminathan Natarajan Trinity Term 2012 Sponsor: BBC Media Action Page 1 of 41 Page 2 of 41 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I would like to thank James Painter, Head of the Journalism Programme and the entire staff of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism for their help and support. I am grateful to BBC New Media Action for sponsoring me, and to its former Programme Officer Tirthankar Bandyopadhyay, for letting me know about this wonderful opportunity and encouraging me all the way. My supervisor Dr Sujit Sivasundaram of Cambridge University provided academic insights which were very valuable for my research paper. I place on record my appreciation to all those who participated in the survey and interviews. I would like to thank my colleagues in the BBC, Chandana Keerthi Bandara, Charles Haviland, Wimalasena Hewage, Saroj Pathirana, Poopalaratnam Seevagan, Ponniah Manickavasagam and my good friend Karunakaran (former Colombo correspondent of the BBC Tamil Service) for their help. Special thanks to my parents and sisters and all my fellow journalist fellows. Finally to Marianne Landzettel (BBC World Service News) for helping me by patiently proof reading and revising this paper. Page 3 of 41 Table of Contents 1 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Challenges to Press Freedom -

PDF995, Job 7

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara First week from nomination: 8th-15th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 94 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); • The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.14, 00% and 1.82%. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda Rajapakse. - Dinamina (43.56%), Thinakaran (56.21%) and Daily News (29.32%). • The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe, of any daily news paper. Dinamina had 28.82%. Thinkaran had 8.67% and Daily News had 12.64%. • Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe, was 10.75%, 5.10% and 11.13% respectively. • The state owned dailies and weeklies had 04 front page Lead stories and 02 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 02 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. State media coverage of two main candidates (in sq.cm% of total election coverage) Mahinda Rajapakshe Ranil W ickramasinghe Newspaper Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable Dinamina 43.56 1.14 10.75 28.88 Silumina 28.82 10.65 18.41 30.65 Daily news 29.22 1.82 11.13 12.64 Sunday Observer 23.24 00 12.88 00.81 Thinakaran 56.21 00 03.41 00.43 Thi. -

Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu

Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu John Harriss with Andrew Wyatt Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 50/2016 | March 2016 Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 50/2016 2 The Simons Papers in Security and Development are edited and published at the School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University. The papers serve to disseminate research work in progress by the School’s faculty and associated and visiting scholars. Our aim is to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the series should not limit subsequent publication in any other venue. All papers can be downloaded free of charge from our website, www.sfu.ca/internationalstudies. The series is supported by the Simons Foundation. Series editor: Jeffrey T. Checkel Managing editor: Martha Snodgrass Harriss, John and Wyatt, Andrew, Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 50/2016, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, March 2016. ISSN 1922-5725 Copyright remains with the author. Reproduction for other purposes than personal research, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), the title, the working paper number and year, and the publisher. Copyright for this issue: John Harriss, jharriss (at) sfu.ca. School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Suite 7200 - 515 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6B 5K3 Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu 3 Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu Simons Papers in Security and Development No. -

An Imperative for Sri Lanka!

ANMEEZAN ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL COMPRISING SCHOLARLY AND STUDENT ARTICLES 53RD EDITION EDITED BY: Shabna Rafeek Shimlah Usuph Shafna Abul Hudha All rights reserved, The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis Sri Lanka Law College Cover Design: Arqam Muneer Copyrights All material in this publication is protected by copyright, subject to statutory exceptions. Any unauthorized of the Law Students’ Muslim Majlis, may invoke inter alia liability for infringement of copyright. Disclaimer All views expressed in this production are those of the respective author and do not represent the opinion of the Law Students’ Muslim Majlis or Sri Lanka Law College. Unless expressly stated, the views expressed are the author’s own and are not to be attributed to any instruction he or she may present. Submission of material for future publications The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis welcomes previously unpublished original articles or manuscripts for publication in future editions of the “Meezan”. However, publication of such material would be at the discretion of the Law Students’ Muslim Majlis, in whose opinion, such material must be worthy of publication. All such submissions should be in duplicate accompanied with a compact disk and contact details of the contributor. All communication could be made via the address given below. Citation of Material contained herein Citation of this publication may be made due regard to its protection by copyright, in the following fashion: 2019, issue 53rd Meezan, LSMM Review, Responses and Criticisms The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis welcome any reviews, responses and criticisms of the content published in this issue. The President, The Law Students’ Muslim Majlis Sri Lanka Law College, 244, Hulftsdorp Street, Colombo 12 Tel - 011 2323759 (Local) - 0094112323749 (International) Email - [email protected] EVENT DETAILS The Launch of the 53rd Edition of the Annual Law Journal -MEEZAN- Chief Guest Hon. -

Islamaphobia and Anti-Muslim Hate in Sri Lanka Note

Islamaphobia and anti-Muslim hate in Sri Lanka Note: The structure of this submission follows the guiding questions raised in the concept note for the online consultation. It provides a synopsis of concepts and a snap shot of issues and includes a number of references to more detailed information and analysis. Definitions Islamaphobia is used in Sri Lanka mainly by Muslim commentators, scholars, a few Islamic scholars and a handful of non-Muslim intellectuals to describe the hatred and fear of Islam by non-Muslims and/or as one of the root causes of anti-Muslim hatred. It is often used in online platforms though not limited to it. Anti- Muslim hate is used to refer to hate campaigns and messaging by non-Muslims targeting Muslims. There is more usage of the term anti-Muslim hate than Islamaphobia and the latter is at times used to describe the former. Historical/political context affecting usage of terms: There are number of factors that influence and affect the usage of these terms. They include: a) Muslim’s historical ethnic claims – pre-independence Muslim political representatives fearing they would be a ‘minority within a minority’ fought hard to establish their own ethnic identity. The British enabled this through a problematic and weak classification titled ‘Moor’ (Ceylon and Coastal). There were also other Muslim ethnic groups such as the Malays. Based on weak ethnic markers (Arab origin, distinct culture) and as they were conversant in both local languages (Tamil and Sinhalese), Muslims became less ethnically distinctive and more commonly identified as a religious group, or as ‘Muslims.’ Nevertheless, claiming an identity distinct from the two larger ethnic groups and seeking recognition as a separate group remains critically important to community representatives and leaders.1 Consequentially, both from outside and inside the community hate, attacks and violence are framed as against ‘Muslims’ rather than ‘Islam’ and renders to the more frequent reference of ‘anti-Muslim’ violence/hate/attacks over Islamaphobia.