Midcentury SW Churches Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archdiocesan Information About Diocesan Priests the Following Is the Most Recent List Abita Springs Marrero Rev

New Orleans CLARION HERALD 6 October 1, 2005 Archdiocesan information about diocesan priests The following is the most recent list Abita Springs Marrero Rev. Joe Palermo, Baton Rouge (Sept. 27) of archdiocesan priests who have Rev. Joseph Cazenavette, St. Edward the Msgr. Larry Hecker, Holy Family, Port Rev. Paul Passant, Destrehan reported to the Department of Clergy their Confessor, Metairie Allen, La. Rev. Wayne Paysse, St. Louis King of present locations: Rev. Beau Charbonnet, St. Anselm, Msgr. Ken Hedrick, St. Angela Merici, France, Baton Rouge Madisonville Metairie Rev. Denver Pentecost, Florida Rev. Harry Adams, St. Joachim, Marrero Msgr. Joseph Chotin, Mandeville Rev. Carroll Heffner, Our Lady of the Pines, Rev. Denzil Perera, Safe Rev. Edmund Akordor, Holy Family, Rev. John Cisewski, St. Hubert, Garyville Chatawa Rev. Nick Pericone, Most Blessed Sacra- Natchez, Miss. Rev. Victor Cohea, Oakvale, Miss. Rev. Luis Henao, St. Margaret Mary, ment, Baton Rouge Rev. Ken Allen, St. Joan of Arc, LaPlace Rev. Patrick Collum, St. Paul, Brandon, Slidell Rev. Anton Perkovic, St. Joseph Abbey Rev. G Amaldoss, St. Pius X, Crown Point Miss. Rev. John Hinton, Safe Rev. John Perino, Holy Family, Luling Rev. Jaime Apolinares, California Rev. Warren Cooper, Immaculate Concep- Msgr. Howard Hotard, Covington Rev. Dr. Tam Pham, St. Anthony, Baton Rev. John Arnone, Holy Name of Mary, tion, Marrero Archbishop Alfred Hughes, Our Lady of Rouge New Orleans Rev. Desmond Crotty, Metairie Mercy, Baton Rouge Rev. Tuan Pham, St. Peter, Reserve Rev. John Asare-Dankwah, Holy Family, Rev. Cal Cuccia, Our Lady of Divine Provi- Rev. Dominic Huyen, California Rev. Anton Ba Phan, Safe Natchez, Miss. -

Cloister Chronicle

THE CLOISTER CHRONICLE ST. JOSEPH'S PROVINCE Condolences The Fathers and Brothers of the Province extend their sympathy and prayers to the Rev . ]. F. Whittaker, O.P., on the death of his mother; to Rev . ]. T. Carney, O.P., on the death of his brother; and to the Very Rev. C. L. Davis, O.P., on the death of his sister; to the Rev. ]. J. Jurasko and S. B. Jurasko on the death of their father. Ordinations On the evening of September 29, at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, Washington, D . C., the following Brothers received the Clerical Tonsure from the Most Rev. Philip Hannan, D.D., Auxiliary Bishop of W ashington: Vincent Watson, Mannes Beissel, Michael Hagan, Cornelius Hahn, D amian Hoesli, Peter Elder, Albert Doshner, Louis Mason Christopher Lozier, Robert Reyes (for the Province of the Netherlands), Joachim Haladus, Raymond Cooney, John Rust and Aquinas Farren. On the following morning, these same Brothers received the Minor Orders of Porter, Lector, Exorcist and Acolyte from Bishop Hannan. On October 1, during a Pontifical Low Mass in the Crypt Church of the Na tional Shrine, Bishop Hannan ordained the following Brothers to the Subdiaconate: Joseph Payne, Paul Philibert, Humbert Gustina, Urban Sharkey, Anthony Breen and Dominic Clifford. Bishop Hannan ordained the following Brothers to the Diaconate on Oct. 2: Magin Borrajo-Delgardo (for the Province of the Most Holy Rosary), Eugene Cahouet, Stephen Peterson, John Dominic Campbell, Brian Noland, Leonard Tracy, Daniel Hickey, Francis Bailie and David D ennigan. Professions On the 16th of August, the Very Rev. -

Alterations and Extensions Supplementary Planning Document

Lewisham local plan Alterations and Extensions Supplementary planning document Draft December 2017 Foreword “The Council is committed to supporting development that allows everyone in Lewisham the opportunity to make the most of their property in a positive way, not just for them but for their neighbours and the community as a whole. Currently there is great local interest in the don’t move - improve approach and the Council wishes to help residents stay in their properties by accommodating their changing needs. Well designed extensions and alterations can increase the amount and quality of accommodation and enhance the appearance of buildings. The improvement and conversion of existing buildings also makes effective use of urban land and makes good environmental sense. Poorly considered proposals can cause harm to the amenities and characteristics of our borough. Through carefully considered alterations and extensions, we have the potential to improve and enhance our community to make Lewisham the best place to live, work and learn in London.” CONTENTS FOREWORD ....................................................................................2 01 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 4 1.1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................5 1.2 WHAT IS A SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENT?............................5 1.3 WHY HAVE AN SPD? ....................................................................................5 -

ORANGES to Hold to Its Stand That Admis- U.N

>- ** V V - m m T W E S t T MONDAY, NOVE^ER > ‘ ilm trl|[^ r lEttrnfns A fin m ItafljrNetiPnHM Ron Vint Om Vedz BMe« The Past NMmn’s Aaaoda- Garbage and refuse, pickup Harold Buckley of the Hart- AIMS * H i e ' mt Town tlon of Temple Chapter, OBS, complaints for the week ending ford Social Security Agency, IT'S MIGlifY iv will meet Wednesday at 8 pjn. Nov. 6 fell to one of the lowest who was scheduled to speak last WViliBigfii Qunera Club will at the home of Mrs. John Trot totals in recent years. Public Tuesday, will apeak on "Medi- iB 40i; mfilt WtdMikIhy at 8 p.m. at First 14,581 ter, 8S Dale Rd. Hostesses will Works Director Walter Fuss re- care” at a meeting of the Man- NICE . TO inotpow, blgl^ tn ^ " m i cJ' :• tb^^BUlMop Hooaa, Vaterana ICe- M be Mrs. W. Sydney' Harrison ported that only 2S calls were Chester Rotary Club tomorrow O R E E M i i n o ^ Z*ark, Ibtat Hartford. and Mrs. R a il Loveland. Mem received for miscellaneous com- at 6:30 p.m. at the Manchester National IS T A M P S i - V' Maneheettsr^A City of ViSk^Chtf^ Ja^ Englert o t the Baatman SAVE TWICE bers are reminded to notify a plaints. Country Club. VOL. LXXXV, NO. 40 (EIGHTEEN PA6ES1 Koidak Co. will preaent a lec hostess If unable to attend. MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 1966 (CbuMlfled AOverOalag « i Pag« 18) ture entitled "Super 8 — llie S to re s Bright New Ijo d k in 8 mm." Holy Family Mothers Circle Manchester WA'TES will meet The Manchester Chapter .of will meet Wednesday at 6:46 tomorrow at the ItaUan Ameri- Verplanck School PTA wUl SPESSQSA will meet tonight p.m. -

As Seen Here in These Pictures of Ranch Houses in Just One Small Community. T

1 Ranch Houses in Georgia: A Guide to Architectural Styles May 2010 Richard Cloues, Ph.D. 2 Ranch Houses in Georgia come in a wide variety – as seen here in these pictures of Ranch Houses in just one small community. 3 Their diversity is extreme -- more so than any other kind of historic house -- and sometimes perplexing. 4 And yet there are recurring patterns of outward appearances and underlying forms. 5 The outward appearances are indicative of different architectural styles applied to Ranch Houses. 6 The variations in the underlying forms of Ranch Houses reveal different Ranch House types (or sub- types). 7 This presentation is about architectural styles. (A complementary presentation discusses the various types of Ranch Houses in Georgia.) 8 It builds upon the residential architectural styles first identified in the 1991 Georgia's Living Places report. In that report, architectural style is defined in two ways: 9 (1) the decoration or ornamentation that has been put on a house in a systematic pattern or arrangement to create a specific visual effect; and/or (2) the overall design of a house including proportions, scale, massing, symmetry or asymmetry, and the relationship among parts such as solids and voids or height, depth, and width. 10 With this definition of architectural style in mind, let’s get our Ranch House identification kit and look at the different architectural styles found on Georgia's Ranch Houses. 11A Four architectural styles predominate: Contemporary the Contemporary (or Eichleresque "California" Contemporary), Rustic (Western) the Eichleresque (or Colonial Revival "Eichler"), the Rustic (or "Western"), and the Colonial Revival. -

Catalogue of an Exhibition of Drawings from the Queensland Architecturalarchive in the Fryer Memorial Library University of Queensland

Catalogue of an Exhibition of Drawings from the Queensland ArchitecturalArchive in the Fryer Memorial Library University of Queensland Published with the assistance of the Friends of the Fryer Library University of Queensland Library St. Lucia 1988 Catalogue of an exhibition Held at the Brisbane City Hall ArtGallery and Museum 1-29 June 1988 ISBN 0 �71 10 6 Researchedand written by Don Watson and FionaGardinet. 2 FOREWORD In April1986the University of Queensland Library submittedto the DesignBoard of the AustraliaCouncil a proposal for assistance in a project to collect Queensland architecturalrecords. The decision to supportthe development of architectural collectionswas made by the Library for a numberof reasons. New interestin the nation's history had led to greater appreciationof the significanceof buildingsas social and culturalrecords. Two collections of records were already held in the Fryer Library- one from the firm A.B. and R.M. Wilson, established inBrisbane in1884, and the other fromthe architect I<arl Langer. The use made of these collections by architects,social historians and students of the finearts attested to their research value. Two years previously, in1984, the Library had published 'A Directory of Queensland Architectsto 1940'by DonaldWatson and Judith McKay. Through this project it was aware of the existence of valuable collectionsof architecturalrecords. No organisation was systematically collecting in this area and there was the need to ensure that thisimportant part of Queensland's heritage was preserved for future research. As a result of the grant received from the Design Board,the Fryer Library has acquired a fine collection of architectural records. The collectiondates fromthe last two decades of the nineteenth century but is particularlystrong in the period between the two world wars. -

Architectural Styles/Types

Architectural Findings Summary of Architectural Trends 1940‐70 National architectural trends are evident within the survey area. The breakdown of mid‐20th‐ century styles and building types in the Architectural Findings section gives more detail about the Dayton metropolitan area’s built environment and its place within national architectural developments. In American Architecture: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, Cyril Harris defines Modern architecture as “A loosely applied term, used since the late 19th century, for buildings, in any of number of styles, in which emphasis in design is placed on functionalism, rationalism, and up‐to‐date methods of construction; in contrast with architectural styles based on historical precedents and traditional ways of building. Often includes Art Deco, Art Moderne, Bauhaus, Contemporary style, International Style, Organic architecture, and Streamline Moderne.” (Harris 217) The debate over traditional styles versus those without historic precedent had been occurring within the architectural community since the late 19th century when Louis Sullivan declared that form should follow function and Frank Lloyd Wright argued for a purely American expression of design that eschewed European influence. In 1940, as America was about to enter the middle decades of the 20th century, architects battled over the merits of traditional versus modern design. Both the traditional Period Revival, or conservative styles, and the early 20th‐century Modern styles lingered into the 1940s. Period revival styles, popular for decades, could still be found on commercial, governmental, institutional, and residential buildings. Among these styles were the Colonial Revival and its multiple variations, the Tudor Revival, and the Neo‐Classical Revival. As the century progressed, the Colonial Revival in particular would remain popular, used as ornament for Cape Cod and Ranch houses, apartment buildings, and commercial buildings. -

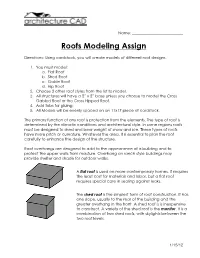

Roofs Modeling Assign

Name: __________________________ Roofs Modeling Assign Directions: Using cardstock, you will create models of different roof designs. 1. You must model: a. Flat Roof b. Shed Roof c. Gable Roof d. Hip Roof 2. Choose 2 other roof styles from the list to model. 3. All structures will have a 2” x 2” base unless you choose to model the Cross Gabled Roof or the Cross Hipped Roof. 4. Add tabs for gluing. 5. All Models will be evenly spaced on an 11x17 piece of cardstock. The primary function of any roof is protection from the elements. The type of roof is determined by the climatic conditions and architectural style. In some regions roofs must be designed to shed and bear weight of snow and ice. These types of roofs have more pitch or curvature. Whatever the area, it is essential to plan the roof carefully to enhance the design of the structure. Roof overhangs are designed to add to the appearance of a building and to protect the upper walls from moisture. Overhang on ranch style buildings may provide shelter and shade for outdoor walks. A flat roof is used on more contemporary homes. It requires the least cost for materials and labor, but a flat roof requires special care in sealing against leaks. The shed roof is the simplest form of roof construction. It has one slope, usually to the rear of the building and the greater overhang in the front. A shed roof is is inexpensive to construct. A variety of the shed roof is the monitor. It is a combination of two shed roofs, with skylights between the two roof levels. -

FORMING FAITH Inspiring Excellence a TRADITION of EXCELLENCE

ARCHBISHOP HANNAN HIGH SCHOOL FORMING FAITH Inspiring excellence A TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE Catholic. Coed. College Prep. Located in Covington, Louisiana. At Archbishop Hannan High School, we take inspiration from the life and ministry of Archbishop Philip Hannan to foster faith, inspire academic excellence and develop character. Founded in 1987 in St. Bernard Parish, Archbishop Hannan Celebrating 30 Years of relocated to Covington in 2008 after Hurricane Katrina Catholic Education and Formation devastated the original campus. Today, we’re big enough (grades 8-12, enrollment 613) to offer a broad curriculum and lots of extracurriculars, yet small enough to feel like a warm and loving family. A family that encourages each student to grow spiritually, intellectually, physically and creatively. FAST A View from Above ... FACTS 613 Current enrollment students from 12 local communities 44% 56% boys girls 24 acre campus 13:1 student/teacher ratio 1:1 8 Our Mission IPad straight years of continuous Archbishop Hannan High School forms men and women of faith, character and scholarship by 21 developing the whole student. Through an academically rigorous education and Christ-centered Program ACT Improvement formation, we prepare and inspire our students to think critically, act with compassion and integrity, Average Class Size and respond as leaders to the needs of a complex and diverse world. Charity Leads FORMING to Perfection Archbishop Philip M. Hannan left an indelible imprint on the city of New Orleans. FAITH Installed as the 11th Archbishop of New Orleans in 1965, he found an archdiocese heavily damaged by Hurricane Betsy. He battled racism, poverty and hunger; founded a television station; even hosted Pope John Paul II’s Apostolic Visit to New Orleans. -

2013-2014 Donors

2013-2014 Donors A. G. Consulting Services, LLC A. P. Keller, Inc. Aaron's Rent to Own Store AARP Belle Chasse Chapter 4034 Ms. Connie M. Abadie Dr. and Mrs. Francis R. Abadie Ms. Jeanne Abadie Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd J. Abadie, Sr. Mr. and Mrs. Robert J. Abadie Mr. and Mrs. William C. Abadie, Sr. Ms. Yvonne C. Abadie Mr. and Mrs. Jose A. Abadin, Jr. Mr. and Mrs. Peter V. Abate Ms. Miriam L. Abate Mr. and Mrs. Rodney J. Abele, Jr. Mr. Keith R. Abide Mrs. Patricia F. Abide Mr. Desmond Ables Mr. and Mrs. Herman J. Abry Academy of Our Lady Deceased 2013-2014 Donors Academy of the Sacred Heart Ms. Mary F. Achary Mr. and Mrs. Michael A. Ackal, Jr. Ms. Danna M. Acker Acme Oyster House Ms. Greta M. Acomb Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Acomb, Jr. Mr. Bernard R. Acosta Mr. Casamere J. Acosta, Jr. Mr. and Mrs. Donald F. Acosta, Sr. Mrs. Linda Acosta Mrs. Dora J. Adair Mr. and Mrs. Byron A. Adams, Jr. Mr. Dale T. Adams Mr. and Mrs. Ellis W. Adams Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth W. Adams Mr. Lon G. Adams Ms. Marguerite L. Adams and Mr. Thomas K. Foutz Mr. Mark W. Adams Ms. Mary L. Adams Deceased 2013-2014 Donors Dr. Yvonne S. Adler and Mr. David V. Adler Mr. and Mrs. Joseph A. Adoue Adventure Quest Laser Tag Ms. Denise Ady John J. Aertker, Jr. Company AFP Greater Northshore Chapter Mr. David Aguilar Mr. Frank Aguilar, Jr. Ms. Maria Aguilar Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd J. -

Aprilmayjune 2006 3-14-06 B

Publication of the National Service Committee of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal PPENTECOSTENTECOSTTodayToday October/November/December 2007 Life in Community Acts 4, St. John’s Bible, see page 9 The ministry of Magnificat p. 3 Charisms & community p. 8 Strengthening ecclesial maturity p. 4 Where do we go from here? p. 10 Blocks to maturity p. 6 Charism of word of wisdom p. 12 Renewing the grace of Pentecost in the life and mission of the church. Chairman’s Editor’s Desk Corner ○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○ by Sr. Martha Jean by Aggie Neck McGarry them more fully to do these very The Renewal as well as other groups things” (Novo Millennio Ineunte, 52). and movements in the Church have A new zeal Tbeen encouraged by Pope John Paul I think that asking for a new zeal is a II to strive for ecclesial maturity. am certain that if we questioned 100 good way to start. It does take a heart Maturity is not always something people on what they think “ecclesial that has zeal for the Lord and the fire with which we wish to deal. Remem- Imaturity” is, we would get 100 an- of the Holy Spirit to begin the task, bering that growth often causes some swers. For me ecclesial maturity is com- but also to bring it to completion. pain we tend to turn a deaf ear to ing to know the truth of the gospel, any encouragement “to grow up.” How- the hope that is in it and living and In order to know the Lord and mature ever, growing can be fun. -

In This Issue

VOL. 24, NO. 9 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE DIOCESE OF VICTORIA IN TEXAS January 2011 Texas Death sentences, Pope Benedict XVI arrives in St. Peter’s Square to visit the Nativity scene after In This Issue . leading a vespers service on New Year’s Eve at the Vatican Dec. 31. (CNS photo/ executions drop Paul Haring) Commitment to in 2010 Pope begins new year with call for Marriage Statement, AUSTIN — Death sentences in Texas have dropped more than 70% since 2003, religious freedom, end to violence p. 2 reaching a historic low in 2010 according By Carol Glatz East. to the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Roman Catholic News Service In particular, the pope condemned an Penalty’s (TCADP) new report, Texas VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Opening attack Jan. 1 against Orthodox Christians Missal Death Penalty Developments in 2010: 2011 with a strong call for religious liberty, in Egypt, calling it a “despicable gesture of The Year in Review. TCADP, an Austin- changes Pope Benedict XVI condemned deadly death.” A bomb that exploded as parishio- based statewide, grassroots advocacy attacks against Christians and announced ners were leaving a church in Alexandria, to affect organization, releases this annual report a new interfaith meeting next fall in As- Egypt, left 25 people dead and dozens music each December in conjunction with the sisi, Italy. more injured. anniversary of the resumption of execu- ministers, At a Mass Jan. 1 marking the World The pope said the attack was part of tions in Texas in 1982. Day of Peace and a blessing the next day, a “strategy of violence that targets Chris- p.