An Evening with Alan Bennett – in Conversation with Michael Stewart and Script Yorkshire – Friday 10 September 2010 – Carriageworks Theatre, Leeds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masterpiece Theatre – the First 35 Years – 1971-2006

Masterpiece Theatre The First 35 Years: 1971-2006 Season 1: 1971-1972 The First Churchills The Spoils of Poynton Henry James The Possessed Fyodor Dostoyevsky Pere Goriot Honore de Balzac Jude the Obscure Thomas Hardy The Gambler Fyodor Dostoyevsky Resurrection Leo Tolstoy Cold Comfort Farm Stella Gibbons The Six Wives of Henry VIII ▼ Keith Michell Elizabeth R ▼ [original for screen] The Last of the Mohicans James Fenimore Cooper Season 2: 1972-1973 Vanity Fair William Makepeace Thackery Cousin Bette Honore de Balzac The Moonstone Wilkie Collins Tom Brown's School Days Thomas Hughes Point Counter Point Aldous Huxley The Golden Bowl ▼ Henry James Season 3: 1973-1974 Clouds of Witness ▼ Dorothy L. Sayers The Man Who Was Hunting Himself [original for the screen] N.J. Crisp The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club Dorothy L. Sayers The Little Farm H.E. Bates Upstairs, Downstairs, I John Hawkesworth (original for tv) The Edwardians Vita Sackville-West Season 4: 1974-1975 Murder Must Advertise ▼ Dorothy L. Sayers Upstairs, Downstairs, II John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Country Matters, I H.E. Bates Vienna 1900 Arthur Schnitzler The Nine Tailors Dorothy L. Sayers Season 5: 1975-1976 Shoulder to Shoulder [documentary] Notorious Woman Harry W. Junkin Upstairs, Downstairs, III John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Cakes and Ale W. Somerset Maugham Sunset Song James Leslie Mitchell Season 6: 1976-1977 Madame Bovary Gustave Flaubert How Green Was My Valley Richard Llewellyn Five Red Herrings Dorothy L. Sayers Upstairs, Downstairs, IV John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Poldark, I ▼ Winston Graham Season 7: 1977-1978 Dickens of London Wolf Mankowitz I, Claudius ▼ Robert Graves Anna Karenina Leo Tolstoy Our Mutual Friend Charles Dickens Poldark, II ▼ Winston Graham Season 8: 1978-1979 The Mayor of Casterbridge ▼ Thomas Hardy The Duchess of Duke Street, I ▼ Mollie Hardwick Country Matters, II H.E. -

A Cream Cracker Under the Settee Talking Heads ->->->-> DOWNLOAD

A Cream Cracker Under The Settee Talking Heads ->->->-> DOWNLOAD 1 / 3 Cream Cracker Under the settee, Bed Among the Lentils and . Need essay sample on Cream Cracker Under the settee . Talking Heads broke new dramatic .A Cream Cracker Under the Settee by Alan Bennett. Doris, a widow, lives alone. His television series Talking Heads has become a modern-day classic, .Cream Cracker Under the Settee Audition Piece One I was glad when shed gone, dictating. I sat for a bit looking up at me and Wilfred on the wedding photo.Alan Bennett's A Cream Cracker Under the Settee . as in the Talking Heads series of monologues that was first . PROJECT ON GARNIER FAIRNESS CREAM Prepared by .A Cream Cracker Under The Settee is a dramatic monologue written by Alan Bennett in 1987 for television, as part of his Talking Heads series for the BBC.How does Alan Bennett Create Sympathy for Doris in A cream cracker under the Settee.'Cream Cracker under the Settee', written by Alan Bennett comes from a series of 1980s monologues called 'Talking Heads'.Cream Cracker Under the Settee: All about Doris A handy resource helping to develop understanding of the ways in which we are encouraged to feel empathy for Doris.A Cream Cracker Under The Settee has 12 ratings and 0 reviews: Published February 13th 2014 by Samuel French Ltd, 11 pages, PaperbackMonologue Of The Cracker Under The Settee. Print . is significant is the cream cracker under the settee. explore is when Doris starts talking about .Sue Wallace, who is currently making audiences go from out-loud laughter to profound sadness in 'A Cream Cracker under the Settee', has worked on Alan Bennet.A Cream Cracker Under the Settee by Alan Bennett. -

Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro Zone)

edition ENGLISH n° 284 • the international DANCE magazine TOM 650 CFP) Pina Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro zone) € 4,90 9 10 3 4 Editor-in-chief Alfio Agostini Contributors/writers the international dance magazine Erik Aschengreen Leonetta Bentivoglio ENGLISH Edition Donatella Bertozzi Valeria Crippa Clement Crisp Gerald Dowler Marinella Guatterini Elisa Guzzo Vaccarino Marc Haegeman Anna Kisselgoff Dieudonné Korolakina Kevin Ng Jean Pierre Pastori Martine Planells Olga Rozanova On the cover, Pina Bausch’s final Roger Salas work (2009) “Como el musguito en Sonia Schoonejans la piedra, ay, sí, sí, sí...” René Sirvin dancer Anna Wehsarg, Tanztheater Lilo Weber Wuppertal, Santiago de Chile, 2009. Photo © Ninni Romeo Editorial assistant Cristiano Merlo Translations Simonetta Allder Cristiano Merlo 6 News – from the dance world Editorial services, design, web Luca Ruzza 22 On the cover : Advertising Pina Forever [email protected] ph. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Bluebeard in the #Metoo era (+39) 011.19.58.20.38 Subscriptions 30 On stage, critics : [email protected] The Royal Ballet, London n° 284 - II. 2020 Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo Hamburg Ballet: “Duse” Hamburg Ballet, John Neumeier Het Nationale Ballet, Amsterdam English National Ballet Paul Taylor Dance Company São Paulo Dance Company La Scala Ballet, Milan Staatsballett Berlin Stanislavsky Ballet, Moscow Cannes Jeune Ballet Het Nationale Ballet: “Frida” BALLET 2000 New Adventures/Matthew Bourne B.P. 1283 – 06005 Nice cedex 01 – F tél. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Teac Damse/Keegan Dolan Éditions Ballet 2000 Sarl – France 47 Prix de Lausanne ISSN 2493-3880 (English Edition) Commission Paritaire P.A.P. -

Bed Among the Lentils’

Études de stylistique anglaise 3 | 2011 Contexte(s) “Instant contextualisation” and readerly involvement in Alan Bennett’s ‘Bed among the Lentils’ Manuel Jobert Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/esa/1605 DOI: 10.4000/esa.1605 ISSN: 2650-2623 Publisher Société de stylistique anglaise Printed version Date of publication: 31 December 2011 Number of pages: 45-58 ISSN: 2116-1747 Electronic reference Manuel Jobert, « “Instant contextualisation” and readerly involvement in Alan Bennett’s ‘Bed among the Lentils’ », Études de stylistique anglaise [Online], 3 | 2011, Online since 27 November 2018, connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/esa/1605 ; DOI : 10.4000/esa.1605 Études de Stylistique Anglaise “INSTANT CONTEXTUALISATION” AND READERLY INVOLVEMENT IN ALAN BENNETT’S ‘BED AMONG THE LENTILS’1 Manuel Jobert Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 – CREA - EA 370 Résumé : Cet article entend montrer la manière dont Alan Bennett parvient à donner vie à des mondes fictionnels de manière concise et efficace. Les lecteurs / spectateurs des monologues se trouvent d’emblée plongés dans un univers qui leur semble familier. Deux stratégies narratives centrales semblent expliquer ce type de réception. L’auteur a en effet recours à ce que je propose d’appeler des « îlots narratifs », c’est-à-dire des saynètes qui permettent de sympathiser avec le narrateur. L’expérience des lecteurs est en outre sollicitée par Alan Bennett : des schèmes mentaux sont renforcés, d’autres modifiés ou précisés et certaines constructions lexico- syntaxiques sont utilisées afin de suggérer un sens implicite. Mots-clés : contexte, îlots narratifs, schèmes, réception, constructions syntaxiques Introduction Talking heads is a series of twelve monologues written by Alan Bennett (1988 / 1998) and filmed for BBC television. -

Curriculum Vitae

Ginny Schiller CDG 9 Clapton Terrace London E5 9BW Casting Director Tel: 020 8806 5383 Mob: 07970 517667 [email protected] curriculum vitae I am an experienced casting director with nearly 20 years in the industry. My casting career began at the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1997 and I went freelance in 2001. I have collaborated on hundreds of productions with dozens of directors, producers and venues, and although my main focus has always been theatre, I have also cast for television, film, radio and commercials. I have been an in-house casting director for Chichester Festival Theatre, Rose Theatre Kingston, English Touring Theatre and Soho Theatre and returned to the RSC in 2005/6 to lead the casting for the Complete Works Season. I currently work closely with Danny Moar on many of the shows for Theatre Royal Bath Productions and with Laurence Boswell at the Ustinov Studio Theatre. I have cast for independent commercial producers as well as the subsidised sector, for the touring circuit, regional, fringe and West End venues, including the Almeida, Arcola, ATG, Birmingham Rep, Bolton Octagon, Bristol Old Vic, City of London Sinfonia, Clwyd Theatr Cyrmu, Frantic Assembly, Greenwich Theatre, Hampstead Theatre, Headlong, Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse, Lyric Theatre Belfast, Marlowe Studio Canterbury, Menier Chocolate Factory, New Wolsey Ipswich, Norfolk & Norwich Festival, Northampton Royal & Derngate, Oxford Playhouse, Plymouth Theatre Royal and Drum, Regent's Park Open Air Theatre, Shared Experience, Sheffield Crucible, Sonia Friedman Productions, Theatre Royal Haymarket, Touring Consortium, Young Vic, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Yvonne Arnaud and Wilton’s Music Hall. I am currently on the committee of the Casting Directors’ Guild, and actively involved in discussions with Equity regarding the casting process and diversity issues across the media. -

Apr-Jun 2018

Theatre Music Art Film Word Heritage APR-JUN 2018 www.thecornhall.co.uk DATE & TIME CATEGORY EVENT PAGE 29 Mar-28 Apr, Exhibition in the 10am-4pm Upper Gallery Test and Measure – Optical Curiosities 4 Weds 4 Apr, 10.30am Matinee 7.30pm Evening Film Paddington 2 (PG) 4 11 Apr-25 May, 10am-4pm Art Exhibition Tony Casement – Breaking News 4 Weds 11 Apr, 10.30am Film Toddler screening – Thomas the Tank Engine 5 Weds 11 Apr, 7.30pm Evening Film Mimosas (15) 5 Thurs 12 Apr, 7pm Screen Arts NT Live – Julius Caesar (15) 5 Sat 14 Apr, 11am Family Saturday Club – Sourpuss 6 Sat 14 Apr, 7.30pm Music Jimmy Aldridge & Sid Goldsmith 6 Weds 18 Apr, 10.30am Matinee 7.30pm Evening Film Loving Vincent (12A) 6 Fri 20 Apr, 7.30pm Music The Jive Aces 7 Sat 21 Apr, 7.30pm Theatre Open Space – Dancing at Lughnasa 7 Weds 25 Apr, 10.30am Matinee 7.30pm Evening Film Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool (15) 7 Thur 26 Apr, 7.30pm Music Keith James – The Songs of Leonard Cohen 8 Fri 27 Apr, 8pm Comedy Corn Hall Comedy Club 8 2 May-2 Jun, Art Exhibition in Harleston & Waveney Art Trail Collective 10am-4pm the Upper Gallery – The Waveney Revisited 9 Weds 2 May, 7.30pm Evening Film Call Me By Your Name (15) 9 Thurs 3 May, 7.30pm Theatre Eastern Angles – Guesthouse 9 Sat 5 May, 7.30pm Music The Bootleg Shadows 10 Tues 8 May, 8pm Theatre Fat Rascal Theatre – Tom & Bunny Save the World 10 Weds 9 May, 7.30pm Evening Film Get Out (15) 10 Thurs 10 May, 7.30pm Music Diss Jazz Club – Ben Holder: Spirit of Stéphane 11 Sat 12 May, 11.30am Family Saturday Club – The Water Babies -

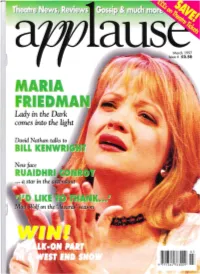

Applause Magazine (Subscriptions), Address

March 1997 ~ -,.~.......... Issue 6 £2.50 Lady in the Dark comes into the light David Nathan talks to I New face I II '" 0] 9 771]64 76]009 I Editor's Letter ime was when new Irish plays, regardless of their quality, rarely performed well at theatre box ulfices in England. Great reviews did not necessarily guarantee great audiences and mounting a new Irish play was something of a high-risk venture. But not anymore. The air is alive with the .J of quolity Blarney as an impressive crop of Iris h dramatists, following in the colourful tradition of " &'ucicault, JB Keane, Oscar Finga l O'Flahertie Wills Wilde, Sean O 'Casey, J M Synge and Samuel =-=_',;<,[( have become de rigueur. The problems of an oppressed, rebellious country, divided both religiously and politically, have for _=: ~J _: been angril y, and poetically expressed by dramatists whose passionate fl air for words is apparent u, -h contemporary Irish pl aywrights as Billy Roche, Tom Murphy, Marina Carr, Frank McGuinness, : ["":b tian Barry, Brian Friel and, the new boy on the block, Martin McDonagh, whose Th e Beauty Q ueen . Lu·"" ne and The CripJlie of Inishmaan have been hits at the Royal Court and the Royal National :-he:Mre respectively. Later in the year the Royal C ourt will be mounting the prolific McDonagh's Connemara trilogy (of ...h lC h Leenane was the first), to be staged in conjunction with the Druid Theatre of Galway; while the " ~ !ll> nal are following lnishmaan with parrs twO and three of their own McDonagh trilogy. -

FRANCES HANNON Make-Up Artist and Hair Designer

FRANCES HANNON Make-Up Artist and Hair Designer AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS Academy Awards - Won - Best Achievement in Make-Up and Hairstyling -- THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL Guild Awards - Won - Best Period and/or Character Hair Styling -- THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL Guild Awards - Won - Best Period and/or Character Make-Up -- THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL British Academy of Film and Television Award - Won - Best Make-Up and Hair Design -- THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL British Academy of Film and Television Award - Nominee - Best Make-Up and Hair Design -- THE KINGS SPEECH British Academy of Film and Television Award - Won - Best Make-Up and Hair Design – THE GATHERING STORM Emmy Award - Nominee – Best Make-Up - CONSPIRACY British Academy of Film and Television Award - Won - Best Make-Up and Hair Designer – THE SINGING DETECTIVE Royal Television Society Award - Won - Best Make-Up and Hair Designer -- THE SINGING DETECTIVE FILM (Selected Credits) ETERNALS Make- Up and Hair Designer Marvel Studios Director: Chloé Zhao Shooting September 2019 ON THE ROCKS P ersonal Make- Up Artist to Bill Murray A24 Director: Sofia Coppola UNTITLED WES ANDERSON PROJECT Make- Up, Hair and Prosthetics Designer TFD Productions Director: Wes Anderson DETECTIVE PIKACHU Make- Up and Hair Designer Universal Pictures Director: Rob Letterman Cast: Ryan Reynolds, Justice Smith, Kathryn Newton JURASSIC WORLD: FALLEN KINGDOM Make- Up, Hair and Prosthetics Designer Universal Pictures Director: J.A Bayona Cast: Chris Pratt, Bryce Dallas Howard, Rafe Spall, Jeff Goldblum, Justice Smith BOURNE 5 Make- Up, Hair and Prosthetics Designer Universal Pictures Director: Paul Greengrass Cast: Matt Damon, Alicia Vikander, Tommy Lee Jones INFERNO (aka HEADACHE) Make- Up and Hair Designer Imagine Entertainment Director: Ron Howard Cast: Tom Hanks, Felicity Jones NOW YOU SEE ME 2 Make- Up and Hair Designer Lionsgate Director: Jon M. -

Eight of Alan Bennett's Talking Heads Come to the Stage in a Series of Unique Double Bills, All of Them with the Same Leading

PRESS BRIEFING ALAN BENNETT’S T A L K I N G H E A D S Following the television broadcast in June this year, eight of Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads monologues will be perFormed in repertoire at the Bridge Theatre. The perFormance schedule can be found below. During April and May, while the Bridge Theatre was closed, the London Theatre Company worked with the BBC to produce Alan Bennett’s landmark Talking Heads monologues. They were broadcast on BBC One in June. Eight of Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads come to the stage in a series of unique double bills, all of them with the same leading actors whose perFormances were universally acclaimed on television. Each of the short plays is a perfectly distilled masterpiece, sometimes disturbing, often hilarious and always profoundly humane. Monica Dolan in The Shrine directed by Nicholas Hytner Tamsin Greig in Nights in the Gardens of Spain directed by Marianne Elliott Lesley Manville in Bed Among the Lentils directed by Nicholas Hytner Lucian Msamati in Playing Sandwiches directed by Jeremy Herrin Maxine Peake in Miss Fozzard Finds Her Feet directed by Sarah Frankcom Rochenda Sandall in The Outside Dog directed by Nadia Fall Kristin Scott Thomas in The Hand of God directed by Jonathan Kent Imelda Staunton in A Lady oF Letters directed by Jonathan Kent Designs are by Bunny Christie, with lighting by Jon Clark, video designs by Luke Halls, sound by Gareth Fry and music by George Fenton. Alan Bennett has been one oF our leading dramatists since the success oF Beyond the Fringe in the 1960s. -

You Didn't Read Our LOCKDOWN UPDATE No.5

'LOCKDOWN UPDATE' no.5 BBC & London Theatre Co. remaking Alan Bennett's Talking Heads with a stellar lockdown cast There can't be many amateur theatre companies that haven't produced their own series of Talking Heads shows... This week, filming began today on new productions of Alan Bennett’s critically acclaimed and multi-award-winning monologues, which first aired on BBC Television in 1988 and 1998. Ten of the original pieces will be re-made with the addition of two new ones written by Bennett last year. They are produced by Nicholas Hytner’s London Theatre Company and Kevin Loader, and will air in the coming months on BBC One. As the British public service broadcaster, the BBC has a key role to play in continuing to offer new programming for our audience at this time of national crisis. The contained nature of Bennett's monologues allowed the opportunity to tell timely and relevant stories while following the latest government guidelines on safe working practices during Covid-19. Alan Bennett told Sardines: "In such difficult circumstances, that the BBC should choose to remount both series of Talking Heads, and produce two entirely new ones, is a comfort and a huge compliment. I hope a new generation of actors will get and give as much pleasure as we did twenty and thirty years ago." The televised monologues will star the cream of today's acting establishment such as Jodie Comer (Killing Eve), Martin Freeman (Sherlock Holmes), Tamsin Greig (Episodes), Maxine Peake (Silk) and Imelda Staunton (Flesh and Blood) to name just five. -

Alan Bennett Writer

Alan Bennett Writer Alan Bennett has been one of our leading dramatists since the success of "Beyond the Fringe" in the 1960s. His television series "Talking Heads" has become a modern-day classic, as have many of his works for the stage, including "Forty Years On", "The Lady In The Van", "A Question of Attribution", "The Madness of George III" (together with the Oscar-nominated screenplay "The Madness of King George") and an adaptation of Kenneth Grahame's "The Wind in the Willows". At the National Theatre, "The History Boys" won Evening Standard, Critics' Circle and Olivier awards, and the South Bank Award. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Publications Fiction Publication Notes Details United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] THE Had the dogs not taken exception to the strange van parked in the royal grounds, UNCOMMON the Queen might never have learnt of the Westminster travelling library’s weekly READER visits to the palace. But finding herself at its steps, she goes up to apologise for 2007 all the yapping and ends up taking out a novel by Ivy Compton-Burnett, last Faber & Faber borrowed in 1989. Duff read though it proves to be, upbringing demands she finish it and, so as not to appear rude, she withdraws another. This second, more fortunate choice of book awakens in Her Majesty a passion for reading so great that her public duties begin to suffer. -

Brotherton Collection MS 20C Theatre West Yorkshire Playhouse

Handlist 123 LEEDS UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Brotherton Collection MS 20c Theatre West Yorkshire Playhouse FROM THE LEEDS PLAYHOUSE TO THE WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE STAGE I In the 1960s, Leeds was the largest City in the country without a regional theatre - a professional producing management presenting plays in its own theatre. A small but enthusiastic group of local people had started a campaign in 1964 for a permanent Repertory Theatre (the full story of the campaign is told in Doreen Newlyn's book "Theatre Connections"). Planning permission had been obtained for a site near the Town Hall but spending cuts led to the postponement of the original plan and in 1969, the Leeds Theatre Trust Ltd (incorporated in 1968) decided to search for existing premises which could be transformed into a temporary theatre. After many disappointments, the University of Leeds agreed to lend the Trust, rent-free, the site of a proposed sports hall which cutbacks had forced them to postpone building. The conditions were that the Trust would build the shell and put the Theatre in it in such a way that it could all be removed at the end of a ten year period, whereupon the University would convert the building into a sports hall. The Theatre, designed by Bill Houghton Evans, was built for £150,000 and after six years of persistence, finally opened on Thursday 16th September 1970 with the world premiere of Alan Plater's "Simon Says". Throughout the campaign, there was tremendous support from members of the acting profession including Peter O'Toole, Dame Diana Rigg, Michael Hordern, Rodney Bewes, Dame Sybil Thorndike, Dame Judi Dench and James Mason.