Autonomy Statute 6 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North-South Divide in Italy: Reality Or Perception?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk EUROPEAN SPATIAL RESEARCH AND POLICY Volume 25 2018 Number 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.25.1.03 Dario MUSOLINO∗ THE NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE IN ITALY: REALITY OR PERCEPTION? Abstract. Although the literature about the objective socio-economic characteristics of the Italian North- South divide is wide and exhaustive, the question of how it is perceived is much less investigated and studied. Moreover, the consistency between the reality and the perception of the North-South divide is completely unexplored. The paper presents and discusses some relevant analyses on this issue, using the findings of a research study on the stated locational preferences of entrepreneurs in Italy. Its ultimate aim, therefore, is to suggest a new approach to the analysis of the macro-regional development gaps. What emerges from these analyses is that the perception of the North-South divide is not consistent with its objective economic characteristics. One of these inconsistencies concerns the width of the ‘per- ception gap’, which is bigger than the ‘reality gap’. Another inconsistency concerns how entrepreneurs perceive in their mental maps regions and provinces in Northern and Southern Italy. The impression is that Italian entrepreneurs have a stereotyped, much too negative, image of Southern Italy, almost a ‘wall in the head’, as also can be observed in the German case (with respect to the East-West divide). Keywords: North-South divide, stated locational preferences, perception, image. 1. INTRODUCTION The North-South divide1 is probably the most known and most persistent charac- teristic of the Italian economic geography. -

Bavaria & the Tyrol

AUSTRIA & GERMANY Bavaria & the Tyrol A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Austria at a Glance ................................................................. 22 Germany at a Glance ............................................................. 26 Packing List ........................................................................... 31 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour ComboCombo,, Munich PrePre----TourTour Extension and Salzbug PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. -

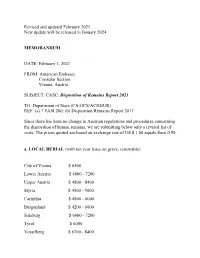

Disposition of Remains Report 2021

Revised and updated February 2021 New update will be released in January 2024 MEMORANDUM DATE: February 1, 2021 FROM: American Embassy Consular Section Vienna, Austria SUBJECT: CASC: Disposition of Remains Report 2021 TO: Department of State (CA/OCS/ACS/EUR) REF: (a) 7 FAM 260; (b) Disposition Remains Report 2017 Since there has been no change in Austrian regulations and procedures concerning the disposition of human remains, we are submitting below only a revised list of costs. The prices quoted are based on exchange rate of US $ 1.00 equals Euro 0.90. a. LOCAL BURIAL (with ten year lease on grave, renewable) City of Vienna $ 6500 Lower Austria $ 4800 - 7200 Upper Austria $ 4800 - 8400 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 6000 Salzburg $ 6000 - 7200 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 6700 - 8400 b. PREPARATION OF REMAINS FOR SHIPMENT TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 6000 Lower Austria $ 6000 - 8900 Upper Austria $ 6000 - 8400 Styria $ 6000 - 8400 Carinthia $ 4800 - 6000 Burgenland $ 4800 - 7200 Salzburg $ 6000 Tyrol $ 6000 Vorarlberg $ 8900 c. COST OF SHIPPING PREPARED REMAINS TO THE UNITED STATES East Coast $ 2900 South Coast $ 2900 Central $ 2900 West Coast $ 3200 Shipping costs are based on an average weight of the casket with remains to be 150 kilos. d. CREMATION AND LOCAL BURIAL OF URN Vienna $ 5800 Lower Austria $ 9000 Upper Austria $ 3400 - 6700 Styria $ 4200 - 5000 Carinthia $ 5000 Burgenland $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (city) $ 4200 - 5900 Salzburg (province) $ 5500 Tyrol $ 5900 Vorarlberg $ 8400 e. CREMATION AND SHIPMENT OF URN TO THE UNITED STATES Vienna $ 3600 Lower Austria $ 4800 Upper Austria $ 3600 Styria $ 3600 Carinthia $ 4800 Burgenland $ 4800 Salzburg $ 3600 Tyrol $ 4200 Vorarlberg $ 6000 e. -

Fascist Legacies: the Controversy Over Mussolini’S Monuments in South Tyrol

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 2013 Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol Gerald Steinacher University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Steinacher, Gerald, "Fascist Legacies: The Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol" (2013). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 144. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/144 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Gerald Steinacher* Fascist Legacies:1 Th e Controversy over Mussolini’s Monuments in South Tyrol2 Th e northern Italian town of Bolzano (Bozen in German) in the western Dolomites is known for breathtaking natural landscapes as well as for its medieval city centre, gothic cathedral, and world-famous mummy, Ötzi the Iceman, which is on dis- play at the local archaeological museum. At the same time, Bolzano’s more recent history casts a shadow over the town. Th e legacy of fascism looms large in the form of Ventennio fascista-era monuments such as the Victory Monument, a mas- sive triumphal arch commissioned by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and located in Bolzano’s Victory Square, and the Mussolini relief on the façade of the former Fascist Party headquarters (now a tax offi ce) at Courthouse Square, which depicts il duce riding a horse with his arm raised high in the Fascist salute. -

Architecture and Nation. the Schleswig Example, in Comparison to Other European Border Regions

In Situ Revue des patrimoines 38 | 2019 Architecture et patrimoine des frontières. Entre identités nationales et héritage partagé Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions Peter Dragsbo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/21149 DOI: 10.4000/insitu.21149 ISSN: 1630-7305 Publisher Ministère de la culture Electronic reference Peter Dragsbo, « Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions », In Situ [En ligne], 38 | 2019, mis en ligne le 11 mars 2019, consulté le 01 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/21149 ; DOI : 10.4000/insitu.21149 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. In Situ Revues des patrimoines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other Europe... 1 Architecture and Nation. The Schleswig Example, in comparison to other European Border Regions Peter Dragsbo 1 This contribution to the anthology is the result of a research work, carried out in 2013-14 as part of the research program at Museum Sønderjylland – Sønderborg Castle, the museum for Danish-German history in the Schleswig/ Slesvig border region. Inspired by long-term investigations into the cultural encounters and mixtures of the Danish-German border region, I wanted to widen the perspective and make a comparison between the application of architecture in a series of border regions, in which national affiliation, identity and power have shifted through history. The focus was mainly directed towards the old German border regions, whose nationality changed in the wave of World War I: Alsace (Elsaβ), Lorraine (Lothringen) and the western parts of Poland (former provinces of Posen and Westpreussen). -

Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites

NO SINGLE SUPPLEMENT for Solo Travelers LAND SMALL GROUP JO URNEY Ma xi mum of 24 Travele rs Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites Undiscovered Italy Inspiring Moments > Be captivated by the extraordinary beauty of the Dolomites, a canvas of snow- dusted peaks, spectacular rock formations and cascading emerald vineyards. > Discover an idyllic clutch of pretty piazzas, INCLUDED FEATURES serene parks and an ancient Roman arena in the setting for Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary romantic Verona, – 7 nights in Trento, Italy, at the first-class Day 1 Depart gateway city Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.” Grand Hotel Trento. Day 2 Arrive in Verona and transfer > Cruise Lake Garda, ringed by vineyards, to hotel in Trento lemon gardens and attractive harbors. Extensive Meal Program > From polenta to strudel to savory bread – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 3 Trento including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 4 Lake Molveno | Madonna di dumplings known as canederli, dine on tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Campiglio | Adamello-Brenta traditional dishes of northeastern Italy. with dinner. Nature Park > Relax over a delicious lunch at a chalet Day 5 Verona surrounded by breathtaking vistas. Your One-of-a-Kind Journey > Explore the old-world charm of Bolzano, – Discovery excursions highlight the local Day 6 Ortisei | Bolzano culture, heritage and history. Day 7 Limone sul Garda | Lake Garda | with its enticing blend of German and Italian cultures. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Malcensine enhance your insight into the region. Day 8 Trento > Experience two UNESCO World Heritage sites. – AHI Sustainability Promise: Day 9 Transfer to Verona airport We strive to make a positive, purposeful and depart for gateway city impact in the communities we visit. -

SOUTH TYROL in COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE1 Stefan Wolff I. Introduction the Instituti

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN COMPLEX POWER SHARING AS CONFLICT RESOLUTION: SOUTH TYROL IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE1 Stefan Wolff I. Introduction Th e institutional arrangements for South Tyrol draw on several traditional con- fl ict resolution techniques but also incorporate features that were novel in 1972 and have remained precedent-setting since then. First of all, South Tyrol can be described as a case of territorial self-governance; that is, “the legally entrenched power of ethnic or territorial communities to exercise public policy functions (legislative, executive and adjudicative) independently of other sources of author- ity in the state, but subject to the overall legal order of the state”.2 Th e forms such regimes can take include a wide range of institutional structures from enhanced local self-government to full-fl edged symmetrical or asymmetrical federal arrange- ments, as well as non-territorial (cultural or personal) autonomy. South Tyrol, in its specifi c Italian context, falls into the category of asymmetric arrangements in its relationship with the central government in Rome when compared to other Italian regions and provinces. However, it also comprises elements of non-territo- rial autonomy internally, especially in relation to the education system. Th ese non-territorial autonomy regimes fl ow from the application to South Tyrol of another well-known and relatively widely used confl ict resolution mechanism—consociational power sharing. Apart from the feature of ‘segmental autonomy’ (i.e., non-territorial autonomy for the two major ethnic groups in the province, primarily in the fi eld of education), South Tyrol also displays other 1 In this chapter I draw on previously published and ongoing research, including Stefan Wolff , “Territorial and Non-territorial Autonomy as Institutional Arrangements for the Settlement of Ethnic Confl icts in Mixed Areas”, in Andrew Dobson and Jeff rey Stanyer (eds.), Contemporary Political Studies 1998, Vol. -

Developments and Effects in South Tyrol and the Alps

Snow DOSSIER Developments and effects in South Tyrol and the Alps Michael Matiu Snow Snow defines the winter landscape, provides vital water resources for ecosystems and agriculture and creates jobs. But climate change is threatening snow. How has snow changed in South Tyrol and the rest of the Alps? What is expected in the future and what will the consequences be? Michael Matiu, Institute for Earth Observation, with the help of Giacomo Bertoldi, Claudia Notarnicola, and Marc Zebisch The intricate beauty of snow crystals is created as they travel through the atmosphere - environmental conditions determine their final shape. (Foto: Bresson Thomas) What is snow? Snow is the most common form of solid precipitation. It consists of ice crystals that are first formed in the atmosphere then grow further while falling. Their final size and shape depend on atmospheric conditions, especially temperature, humidity, and wind. On the ground, snow accumulates to form the snow cover. The texture, size and shape of the snow grains change over time depending on surrounding conditions, such as temperature which causes melting and refreezing, wind transport or subsequent snowfall causing compression. Over the winter season, the snow cover accumulates a complex multi-layer structure, reflecting the weather conditions during and after each snowfall. The snowpack is a complex structure, its layers tell the story of the winter from the first to the most recent snowfall. (Foto: David Newman) When does it snow? Snow feeds on moisture and cold temperatures in the atmosphere. Snow reaches the ground if surface temperatures are below 0°C. In a few specific cases snow can also reach the ground in temperatures of up to +5°C. -

Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites

NO SINGLE SUPPLEMENT for Solo Travelers LAND SMALL GROUP JO URNEY Ma xi mum of 24 Travele rs Trentino, South Tyrol & the Dolomites Undiscovered Italy Inspiring Moments > Be captivated by the extraordinary beauty of the Dolomites, a canvas of snow- dusted peaks, spectacular rock formations and cascading emerald vineyards. > Discover an idyllic clutch of pretty piazzas, INCLUDED FEATURES serene parks and an ancient Roman arena in the setting for Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary romantic Verona, – 7 nights in Trento, Italy, at the first-class Day 1 Depart gateway city Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.” Grand Hotel Trento. Day 2 Arrive in Verona and transfer > Cruise Lake Garda, ringed by vineyards, to hotel in Trento lemon gardens and attractive harbors. Extensive Meal Program > From polenta to strudel to savory bread – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 3 Trento including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 4 Lake Molveno | Madonna di dumplings known as canederli, dine on tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Campiglio | Adamello-Brenta traditional dishes of northeastern Italy. with dinner. Nature Park > Relax over a delicious lunch at a chalet Day 5 Verona surrounded by breathtaking vistas. Your One-of-a-Kind Journey > Explore the old-world charm of Bolzano, – Discovery excursions highlight the local Day 6 Ortisei | Bolzano culture, heritage and history. Day 7 Limone sul Garda | Lake Garda | with its enticing blend of German and Italian cultures. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Malcensine enhance your insight into the region. Day 8 Trento > Experience two UNESCO World Heritage sites. – AHI Sustainability Promise: Day 9 Transfer to Verona airport We strive to make a positive, purposeful and depart for gateway city impact in the communities we visit. -

Pergher Cover

MAX WEBER PROGRAMME EUI Working Papers MWP 2009/08 MAX WEBER PROGRAMME BORDERLINES IN THE BOR DERLANDS: DEFINING DIFFERENCE THROUGH HISTORY, RACE , AND " " CITIZENSHIP IN FASCIST ITALY Roberta Pergher EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE , FLORENCE MAX WEBER PROGRAMME Borderlines in the Borderlands: Defining difference through history, “race”, and citizenship in Fascist Italy ROBERTA PERGHER EUI W orking Paper MWP 2009/08 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. The author(s)/editor(s) should inform the Max Weber Programme of the EUI if the paper is to be published elsewhere, and should also assume responsibility for any consequent obligation(s). ISSN 1830-7728 © 2009 Roberta Pergher Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract The paper discusses the colony in Libya and the province of South Tyrol under Fascism. It focuses on their status as “borderlands” and what that meant in terms of defining the difference between the native populations on the one hand and the immigrant Italian population on the other. In particular, the paper analyzes the place afforded to the Libyan and the South Tyrolean populations in Italian ideology and legislation. It discusses the relevance of the myth of Rome for Italy’s expansion and analyzes various taxonomies of difference employed in the categorization of the “other,” in particular racial and religious markers of difference. -

The South Tyrol Model: Ethnic Pacification in a Nutshell Written by Roland Benedikter

The South Tyrol Model: Ethnic Pacification in a Nutshell Written by Roland Benedikter This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The South Tyrol Model: Ethnic Pacification in a Nutshell https://www.e-ir.info/2021/07/19/the-south-tyrol-model-ethnic-pacification-in-a-nutshell/ ROLAND BENEDIKTER, JUL 19 2021 Avoiding the return of tribal politics – and political tribes – by institutionalizing group diversity has become one priority in the age of re-globalization and populism. The unique diversity arrangement of the small autonomous area of South Tyrol, in the midst of the European Alps, provides a much sought-after counter-model to the return of political tribalism in the clothes of ethnonationalism. This model of ethnicity-inclusive territorial autonomy is not dependent on the daily goodwill of politicians and citizens as many others are but is institutionalized through the anchorage in the national Italian constitution and thus has the ability to impose “tolerance by law”. The international framework could not be more timely to make this model an example. The current trend of re- nationalization favors the return of mono-narratives of identity and ethnic belonging not only in Europe but on a global scale. Yet Europe, as the continent which over the past half-century has found some of the most successful models of politically and juridically arranging ethnic diversity and cultural difference, is particularly challenged by such a trend. -

The South Tyrol Question, 1866–2010 10 CIS ISBN 978-3-03911-336-1 CIS S E I T U D S T Y I D E N T I Was Born in the Lower Rhine Valley in Northwest Germany

C ULTURAL IDENT I TY STUD I E S The South Tyrol Question, CIS 1866–2010 Georg Grote From National Rage to Regional State South Tyrol is a small, mountainous area located in the central Alps. Despite its modest geographical size, it has come to represent a success story in the Georg Grote protection of ethnic minorities in Europe. When Austrian South Tyrol was given to Italy in 1919, about 200,000 German and Ladin speakers became Italian citizens overnight. Despite Italy’s attempts to Italianize the South Tyroleans, especially during the Fascist era from 1922 to 1943, they sought to Question, 1866–2010 Tyrol South The maintain their traditions and language, culminating in violence in the 1960s. In 1972 South Tyrol finally gained geographical and cultural autonomy from Italy, leading to the ‘regional state’ of 2010. This book, drawing on the latest research in Italian and German, provides a fresh analysis of this dynamic and turbulent period of South Tyrolean and European history. The author provides new insights into the political and cultural evolution of the understanding of the region and the definition of its role within the European framework. In a broader sense, the study also analyses the shift in paradigms from historical nationalism to modern regionalism against the backdrop of European, global, national and local historical developments as well as the shaping of the distinct identities of its multilingual and multi-ethnic population. Georg Grote was born in the Lower Rhine Valley in northwest Germany. He has lived in Ireland since 1993 and lectures in Western European history at CIS University College Dublin.