UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk Kunstner Listen

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk kunstner Listen Stacy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/stacy-3503566/albums The Idan Raichel Project https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/the-idan-raichel-project-12406906/albums Mig 21 https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mig-21-3062747/albums Donna Weiss https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/donna-weiss-17385849/albums Ben Perowsky https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ben-perowsky-4886285/albums Ainbusk https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ainbusk-4356543/albums Ratata https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ratata-3930459/albums Labvēlīgais Tips https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/labv%C4%93l%C4%ABgais-tips-16360974/albums Deane Waretini https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/deane-waretini-5246719/albums Johnny Ruffo https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/johnny-ruffo-23942/albums Tony Scherr https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/tony-scherr-7823360/albums Camille Camille https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/camille-camille-509887/albums Idolerna https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/idolerna-3358323/albums Place on Earth https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/place-on-earth-51568818/albums In-Joy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/in-joy-6008580/albums Gary Chester https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/gary-chester-5524837/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums -

Efficacy of a Novel Thoracopelvic Orthosis in Reducing Lumbar Spine Loading and Muscle Fatigue in Flexion: a Study with Weighted Garments

Efficacy of a Novel Thoracopelvic Orthosis in Reducing Lumbar Spine Loading and Muscle Fatigue in Flexion: A Study with Weighted Garments by Daniel D. Johnson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Mechanical Engineering) in the University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Albert J. Shih, Co‐Chair Professor James A. Ashton‐Miller, Co‐Chair Professor Thomas J. Armstrong Assistant Professor Paul Park from: Iron Man Vol. 1, No. 300, Jan. 1994 (pp. 39-42) New York: Marvel Comics For my parents and students …Oh, and Sheamus ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank all those who have supported and assisted me along the way to completing the work for my doctoral program, including: Leah Buechley, Adam Brzezinski, Robert Coury, Alicia Davis (and the orthotists at the University of Michigan Orthotics & Prosthetics Center), Robert Dodde, Toby Donajkowski, Patrick Hughes, Jennifer Keller, Janet Kemp, Anne Kirkpatrick, Achin Masli, Ronald McCarty, Connor Moelmann, Hannah Perner‐ Wilson, Mary Ramirez, Corwin Stout, and Grace Wu…not to mention all of my long‐suffering test subjects. I also owe a special thanks to Massimo Banzi (and the entire team behind the ArduinoTM platform), as well as SparkFun® Electronics: two pioneers of open‐source hardware design. iii Table of Contents Dedication .................................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. -

Halloween Magazine

Shelagh National School HALLOWEEN NEWSLETTER Welcome to our Halloween Magazine. We hope that you enjoy reading about us and that you do all the puzzles and quizzes in our mag. Hannah Montana is one of my favourite celebrities. Her real name is Miley Cyrus but that’s not her real name her real name is Destiny Hope Cyrus. She was in ‘Hannah Montana The Movie’. Leona Lewis is cool and she won the ‘ X Factor ’ in 2007. She has a song called ‘ Keep Bleeding ’ it is my favourite song of hers. The Sugarbabes has a lot of songs. The names of the ‘ Sugarbabes ‘ are Amelle Berrabah, Keisha Buchanan and Heidi Range. They have sold lots of songs, my favourite song is ‘ About you Now ’. The Saturdays are cool. They have millions of songs, One of there songs is called “I just can’t get enough”. Their names are Una Healy, Frankie Sand- ford, Rochelle Wiseman, Mollie King and Vanessa White. By Chloe This Magazine has been published by senior class in Shelagh NS. Dundalk Halloween Issue Articles for next edition to snsoffice @eircom.net before Dec 8th I was swimming in the pool one day. Trying to hold my breathe under the water. I started swimming with my eyes closed. Then I banged into this boy and kissed him. My face went red. I was so embarrassed. From Oppsy Daisy. We were all queuing for a concert. I was so excited that I needed to go to the toilet. I stood up after I was done. I tripped and fell out the door with my underwear around my ankles. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

CONTENTS Introduction John R. Gallagher and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss 3 SECTION 1: GETTING STARTED: INVENTING, BRAINSTORMING, AND MANAGING 1 Love, Beauty, and Truth: On Finding a Dissertation Topic Lynn Z. Bloom 13 2 Sit Down and Write, Get Up and Move Gesa E. Kirsch 17 3 Double Dipping Andrea Abernethy Lunsford 21 4 The Importance of Stories Nancy G. Barrón 25 5 Overcoming the Clinandrium Conundrum Carrie Strand Tebeau 28 6 YouCOPYRIGHTED Can Do That in Rhetoric and CompositionMATERIAL Byron Hawk 32 NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION 7 What’s Interesting? Originality and Its Discontents John Trimbur 35 8 Start with What You Know Ashanka Kumari 38 9 Believe in Yourself and in Your Ability to Join Public and Scholarly Conversations Heidi A. McKee 41 viii CONTENTS 10 Refine Your Rhetorical Exigence Naomi Silver 45 11 Be a Content Strategist Michael J. Faris 49 12 Storyboarding Your Writing Projects Chris M. Anson 53 13 Invention and Arrangement while Driving: Writing for the Commute Jim Ridolfo 57 14 Chip Away Cruz Medina 60 15 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Research Hour Ellen Barton 62 16 Keeping with and Thinking Through: On Maintaining a Daily Work Log Jody Shipka 66 17 Timing Matters: Focus on Achievable Tasks Michael Baumann 69 18 A WPA/First- Time Mom’s Guide to Producing the First BookCOPYRIGHTED for Tenure MATERIAL Staci Perryman-NOT Clark FOR 72 DISTRIBUTION 19 Community Writing: From Classroom to Workplace and Back Stephen A. Bernhardt 77 20 Not a Draft but Materials Joseph Harris 82 21 You Will Not Be Able to Stay Home: Quantitative Research in Writing Studies Norbert Elliot 84 Contents ix 22 Practicing WHIMSY Jenn Fishman 90 23 Trust the Process Kathleen Blake Yancey 96 SECTION 2: GETTING FEEDBACK: SHARING DRAFTS, COLLABORATING, AND (RE)DEVELOPING 24 Writing Is/as Communal Trixie G. -

Sugababes Catfights and Spotlights Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sugababes Catfights And Spotlights mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul / Pop Album: Catfights And Spotlights Released: 2008 Style: Soul, Ballad, Synth-pop, House MP3 version RAR size: 1492 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1821 mb WMA version RAR size: 1701 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 539 Other Formats: MMF MP3 TTA AUD MP1 MIDI FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Girls Alto Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone – Scott GarlandArranged By [Brass] – James TreweekEngineer – Dave PalmerKeyboards, Programmed By – Si Hulbert, Si 1 3:11 HulbertMixed By – Tom ElmhirstMixed By [Assistant] – Dan Parry*Producer – Melvin Kuiters, Si HulbertProducer [Vocals] – Mike StevensTrumpet – Graham Russell Written-By – Anna McDonald, Keisha Buchanan, Nicole Jenkinson You On A Good Day Arranged By, Producer – Klas ÅhlundBass, Guitar, Percussion, Piano, Programmed By – Klas ÅhlundEngineer [Vocals, Assistant] – Werner FreistätterHorns – Per 2 3:26 "Ruskträsk" Johansson, Viktor BrobackeMixed By – Jeremy WheatleyMixed By [Assistant] – Richard EdgelerProgrammed By [Additional] – "Phat" Fabe*Written-By – Keisha Buchanan, Klas Åhlund No Can Do Bass, Guitar – George AstasioEngineer [Brass] – Spencer DewingEngineer [Vocals, Assistant] – Xavier StephensonEngineer [Vocals] – Matt LawrenceKeyboards, Programmed By – Jason Pebworth, Jon Shave, Si HulbertKeyboards, Programmed By, 3 3:10 Producer [Additional] – Melvin KuitersMixed By – Jeremy WheatleyMixed By [Assistant] – Richard EdgelerProducer – Si Hulbert, The Invisible MenSaxophone – Jim HuntTrombone – Nichol Thompson*Trumpet -

Welcome to the New Carnegie Reporter

VOLUME 7 / NUMBER 5 / FALL 2015 CARNEGIE REPORTER WELCOME TO THE NEW CARNEGIE REPORTER n 2000, Carnegie Corporation of New York published the first issue of the Reporter. It was meant to be “a magazine simply about ideas…a hub for foundation ideas in the United States and abroad.” Today’s Reporter has a brand-new look—it’s bigger, with more room for colorful illustrations and striking photographs—and Imore readable, with generous white space and a seamless flow from story to story. Yet its intention is the same as on day one—the sharing of important ideas. Our cover story takes you to the Arab world, to learn how courageous social scientists are conducting groundbreaking research in a tumultuous time. Fifty years after the signing of the Voting Rights Act we assess the impact of Shelby v. Holder and see what the Corporation’s grantees are doing to make voting easier and less restrictive. Our education story shows how more effective math courses are helping community college students get ahead. There’s a dramatic photo essay on Russia; and the latest issue of Carnegie Results, bound into this issue, tells the story of a successful workshop series aimed at advancing Jewish-Muslim engagement. A letter from Vartan Gregorian, President of Carnegie Corporation, is featured in every Reporter. In this issue he writes about the negative impact of data overload on knowledge acquisition. Fifteen years ago, introducing the magazine, he wrote, “We hope it will help you understand Carnegie Corporation and its philosophies on education, democracy, international peace…the areas in which we currently concentrate our grantmaking. -

Flyer News, Vol. 62, No. 10

TUESDAY, NOV. 11, 2014 NEWS // UD alumnus, Vietnam vet- A&E // Cincy-based rock band re- OPINIONS // What makes something SPORTS // Women’s soccer wins VOL. 62 NO. 10 eran remembered by family, friends, leases new album, pg. 19. art? pg. 7. A-10 championship at Baujan, pg. 20. jacket, pg. 5. RudyFlyer is ready to rally for basketball sea- son. Photo by Zoey Xia/ FLYER NEWS Staff Photographer CHRIS BENDEL Sports Editor 2014–2015 Editor’s Note: Page numbers (pg.) indicate where in-depth coverage can be found on the topic in the compre- BASKETBALL hensive preview located on pgs. 9-16. Like any coach coming off of a successful season, University PREVIEW of Dayton head men’s basketball coach Archie Miller draws a line in the sand between the past and the present. Last year, the Flyers finished ranked No. 18 in the final USA Today Coaches Poll, fresh off of an Elite Eight run and a Cinderella story told around the nation. Campus ex- ploded during the historic, postsea- son run uniting students, alumni and the greater Dayton area. The team’s 26 wins were the third-most in school history (pg. 14). For Miller and the Flyers, the accolades from last season will not have any bearing on the success of this current group of Flyers. How- ever, Miller hopes for one important Sophomore guard Scoochie Smith, pictured leading the charge Saturday, will command the UD offense this season. Chris Santucci/Photo Editor thread from last year’s magical run to carry over: student passion. ple are going to say [UD] throws a lot UD opened the season with a 96- giate possessions. -

Das Internet Als Informationsmittel Für Popmusik – Ein Vergleich Ausgewählter Websites

Das Internet als Informationsmittel für Popmusik – ein Vergleich ausgewählter Websites Diplomarbeit im Fach Musikbibliotheken Studiengang Öffentliche Bibliotheken der Fachhochschule Stuttgart – Hochschule der Medien Monika Höfig Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Krueger Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Manfred Nagl Bearbeitungszeitraum: 15. Juli 2002 bis 15.Oktober 2002 Stuttgart, Oktober 2002 Kurzfassung 2 Kurzfassung Die vorliegende Diplomarbeit befasst sich mit dem Thema „Das Internet als In- formationsmittel für Popmusik“. Es werden Bewertungskriterien aufgestellt, nach denen man Internetseiten untersuchen kann. Danach werden exempla- risch vier Websites mit allgemeinen Informationen betrachtet. Anschließend werden Homepages mehrerer Bands und Einzelkünstler der Popmusik unter- sucht. Hierbei wird die offizielle Homepage einer Fansite gegenübergestellt. Es folgt eine Bewertung der gesichteten Websites und eine Schlussbemerkung. Schlagwörter: Internet, Informationsvermittlung, Popmusik, Untersuchung, Bewertung Abstract This thesis deals with the topic „The Internet as information resource for pop music“. Some assessment criteria for the evaluation of internet pages are set up. Following this, four web sites offering general information will be considered. Subsequently we will examine the home pages of several pop music bands and single artists, and we will contrast their official home page to a fan site. The the- sis concludes with a rating of the sighted web sites and a final remark. Keywords: Internet, reference service, pop music, analysis, -

Stargate | Oddity Central - Collecting Oddities

Stargate | Oddity Central - Collecting Oddities http://www.odditycentral.com/tag/stargate Home About Advertise Contact Contribute Disclaimer Privacy policy Search for: Pics News Videos Travel Tech Animals Funny Foods Auto Art Events WTF Architecture Home Father And Son Build Awesome Backyard Stargate By Spooky onJune 16th, 2010 Category: Pics , Tech Comments Off Back in 2005, when Stargate was the coolest sci-fi series around, sg1archive user ‘mango’ teamed up with his father to build a sweet replica of the stargate . 2 The project began in AUTOCAD, where the first blueprints were drawn. Since they didn’t have access to a plotter, plans had to be printed on A4 paper and stuck together, in a circle. The small details of the gate had to Tweet be drawn up from scratch, using photos and video footage. The skeleton of the gate is made up of 18 X-shaped pieces, and the spinning part is made from small planks. 89 The intricate stargate symbols had to be painstakingly carved, from wood, and chevrons first had to be carved from Styrofoam. The back of the stargate, though painted in gray, is totally fake, but the front looks realistic enough, with chevrons locking and everything. Thanks to an inner track, it even spins. Mango wasn’t too satisfied with the paint-job, but all in all this is a geeky masterpiece, just like the Stargate Share home-cinema . Be sure to check the video Mango made, at the bottom of the post. .. Subscribe via Rss Via Email Follow our Tweets on Twitter! 1 of 3 7/11/2012 9:54 PM Stargate | Oddity Central - Collecting Oddities http://www.odditycentral.com/tag/stargate Oddity Central on Facebook Like 8,667 people like Oddity Central . -

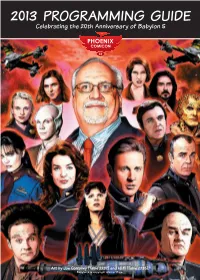

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20Th Anniversary of Babylon 5

2013 PROGRAMMING GUIDE Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of Babylon 5 Art by Joe Corroney (Table 2237) and Hi Fi (Table 2235). Babylon 5 is copyright Warner Bros. 2 PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM PHOENIX COMICON 2013 • PROGRAMMING GUIDE • PHOENIXCOMICON.COM 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Hyatt Regency Map .....................................................6 Renaissance Map ...........................................................7 Exhibitor Hall Map .................................................. 8–9 Programming Rooms ........................................... 10–11 Phoenix Comicon Convention Policies .............12 Exhibitor & Artist Alley Locations .............14-15 Welcome to Phoenix Comicon, Guest Locations...........................................................16 Guest Bios .............................................................. 18–22 the signature pop-culture event of Programming Schedule ................................. 24–35 the southwest! Gaming Schedule ..............................................36–42 If you are new to us, or have never been to a “comicon” before, we welcome you. Programming Descriptions.........................44–70 This weekend is the culmination of efforts by over seven hundred volunteers over the past twelve months all with a singular vision of putting on the most fun convention you’ll attend. Festivities kick off Thursday afternoon and continue throughout the weekend. Spend the day checking out the exhibitor hall, meeting actors and writers, buying that hard to -

Minutes of the Special Meeting, Public Hearing And

MINUTES OF THE SPECIAL MEETING, PUBLIC HEARING AND WORKSHOP OF THE HYDE PARK TOWN BOARD VIRTUAL MEETING HELD VIA ZOOM AND LIVE STREAMED ON YOUTUBE ON NOVEMBER 16, 2020 AT 6:00 PM PRESENT: SUPERVISOR AILEEN ROHR COUNCILMAN NEIL KRUPNICK COUNCILMAN DAVID RAY COUNCILMAN JOSEPH MARRINE COUNCILMAN KENNETH SCHNEIDER ATTORNEY TO THE TOWN WARREN S. REPLANSKY TOWN CLERK DONNA McGROGAN Supervisor Rohr: Well good evening everyone. And welcome to the virtual meeting of the Hyde Park Town Board today is Monday, November 16th. And I hope everyone is well and preparing for a quiet Thanksgiving. Please join me. While we pledge Allegiance to the Flag. I Pledge Allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands one nation under God, indivisible with Liberty and Justice for all. Supervisor Rohr: It reminded me of how my family sings happy birthday, so, okay, well good. So, may I have a motion to accept the minutes of the November 2nd meeting? MOTION: Councilman Schneider: SECOND: Councilman Ray VOICE VOTE: ALL IN FAVOR: 5 ALL OPPOSED: 0 CARRIED Supervisor Rohr: Okay, So, we do have a couple of adjustments to our agenda tonight and I'd like to seek a motion to amend Resolution number three because we are taking out what are we taking out Ken? Pipe cleaning? Councilman Schneider: We are taking out number three, we're going to remove the base and pipe cleaning from the resolution. Supervisor Rohr: This as per the request of the Highway Super. And then we are also adding Resolutions 13 and 14. -

Empowering Congress on Nuclear Security: Blueprints for a New Generation July 2018

An Arms Control Association and Partnership for a Secure America Report Empowering Congress on Nuclear Security: Blueprints for a New Generation July 2018 Jack Brosnan, Andrew Semmel, Nathan Sermonis, and Kingston Reif A Forum on the Arms Trade Report An Arms Control Association and Partnership for a Secure America Report Empowering Congress on Nuclear Security: Blueprints for a New Generation July 2018 Jack Brosnan, Andrew Semmel, Nathan Sermonis, and Kingston Reif About the Authors Jack Brosnan is a Program Associate at Partnership for a Secure America. His focus includes non-proliferation, nuclear security, and the nexus of transnational smuggling and terrorism. Prior to joining PSA Jack spent several years at MIX working to improve delivery of financial services in developing countries. He has also worked as a researcher with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the School of International Service at American University, focusing on projects in corruption, transnational crime, terrorism, and international security. He holds an M.A. in International Affairs from American University’s School of International Service, and a B.A. in Political Science from the University of Massachusetts Boston. Dr. Andrew Semmel is the Chairman of the Board of Directors of Partnership for a Secure America. Since January 2008, Dr. Semmel has been a private consultant at AKS Consulting. Dr. Semmel joined the Department of State in Spring 2003 as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Nuclear Nonproliferation in the Department’s Bureau of Nonproliferation and continued in that role in the newly formed Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation. From September 2001 to January 2003, he served as the Executive Director of the U.S.-China Security Review Commission.