Editorial Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crop Area, Condition and Stage

Foreword The Government of Zimbabwe has continued to exhibit its commitment for reducing food and nutrition insecurity in Zimbabwe. Evidence include the culmination of ZimASSET’s Food and Nutrition Security Cluster and the multi-sector Food and Nutrition Security Policy (FNSP). Recognising the vagaries of climate variabilities and the unforeseeable potential livelihood challenges, Government put in place structures whose mandates are, among other things to provide early warning information for early actioning. The Food and Nutrition Council, through the ZimVAC, is one of such structures which strives to fulfil the aspirations of the FNSP’s commitment number 6 of providing food and nutrition early warning information. In response to the advent of the El Nino phenomena which has resulted in the country experiencing long dry spells, the ZimVAC undertook a rapid assessment focussing on updating the ZimVAC May 2015 results. The lean season monitoring focused on the relevant food and nutrition security parameters. The process followed a 3 pronged approach which were, a review of existing food and nutrition secondary data, qualitative district Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and for other variables a quantitative household survey which in most cases are representative at provincial and national level. This report provides a summation of the results for the 3 processes undertaken and focuses on the following thematic areas: the rainfall season quality, 2015/16 agricultural assistance, crop and livestock condition, food and livestock markets, gender based violence, household income sources and livelihoods strategies, domestic and production water situation, health and nutrition, food assistance and a review of the rural food security projections. -

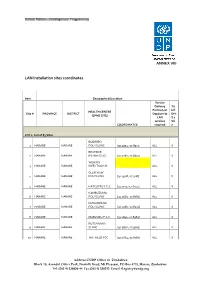

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

February 2011

Zimbabwe Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin Number 102 Epidemiological week 10 (week ending 13 March) March 2011 Highlights Malaria outbreaks in Kadoma and Makoni Figure 1: Cumulative Cholera Cases since 1 January 2011 Cholera cases reported in Chiredzi Contents Chipinge 133 A. General context Mutare 86 B. Epidemic prone diseases C. Events of public health concern in the region Buhera 66 D. Preparedness Chiredzi E. Timeliness and completeness of data 42 F. Recommendations for action/follow up Bikita 42 Annex 1: National summary of cases/deaths by condition District Murewa 5 by week Annex 2: Standard case definitions and alert/action Chimanimani 4 epidemic thresholds Kadoma 2 Mutasa 1 A. General context 0 50 100 150 Cholera cases Cholera continues to be reported in week 10 of 2011, having spilled over from 2010. Since week 45 of Figure 2: Zimbabwe Cholera Epicurve, Week 5, 2010 to Week 10, 2011 2010, no new outbreaks of measles have been reported, although the situation is being closely 200 monitored. We are amidst the malaria season and 180 malaria outbreaks are now being reported. Within the C 160 region, suspected Rift Valley fever has been reported h 140C in South Africa. o 120a l 100s B. Epidemic prone diseases e e80 r 60s Cholera 40 a 20 Nine out of the 62 districts, namely: Bikita, Buhera, 0 17 33 5 9 13 21 25 29 37 41 45 49 1 5 9 Chimanimani, Chipinge, Chiredzi, Kadoma,Murewa, 1 Mutare and Mutasa have reported cases since the start of 2011. There were 381 cumulative cases: 324 2010 2011 suspected cases, 57 laboratory confirmed cases and 7 Epidemiological Week Number by year th deaths reported by the 13 March 2011. -

John H. Peterson, Jr., Professor, Department of Sociology And

BOTTOM UP DEVELOPMENT IN DECENTRALIZED COMMON PROPERTY REGIMES: THE EXPERIENCES OF TWO DISTRICT COUNCILS IN SOUTHEASTERN ZIMBABWE John H. Peterson, Jr., Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, PO Drawer C, Mississippi State, MS 39762; Fulbright Visiting Lecturer 1990-1991, Centre for Applied Social Science, University of Zimbabwe, PO Box MP 167, Mount Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe Paper presented at the International Association for the Study of Common Property, Common Property Conference, Winnipeg, Canada, September 26 - 29, 1991 The Communal Areas Management Program for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) in Zimbabwe seeks to substitute decentralized management and control of natural resources, especially wildlife, for centralized ownership and control. The preservation and utilization of Zimbabwe's natural resources through the CAMPFIRE program involves some important issues in addition to decentralization including conservation through utilization, and sustained development. A fifteen minute presentation can not begin to cover even one of these issues. I am focusing on decentralization because I was struck by the frequency with which leaders at the national and even district level continue to question the degree to which people at the community level are competent to made decisions about common property resources. Decentralization of common property resources raises the question of how far and to whom. There are no simple answers. But there are many potential recipients for decentralized control, each with a case for maintaining controls at particular levels or within some existing institutions. The greatest devolution of management would be to socio- governmental units with the least formal structures - the village and the ward. These people are most familiar with the wildlife and the practical realities of its management. -

Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report

20 16 Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report '' CARG members in Chipinge meet for drug refill in the community. Photo Credits// FHI 360 Zimbabwe'' This study is made possible through the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID.) The contents are the sole responsibility of the Zimbabwe HIV care and Treatment (ZHCT) Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. FOREWORD The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) through the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is committed to strengthening the linkages between public health facilities and communities for HIV prevention, care and treatment services provision in Zimbabwe. The Ministry acknowledges the complementary efforts of non-governmental organisations in consolidating and scaling up community based initiatives towards achieving the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ targets aimed at ending AIDS by 2030. The contribution by Family Health International (FHI360) through the Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment (ZHCT) project aimed at increasing the availability and quality of care and treatment services for persons living with HIV (PLHIV), primarily through community based interventions is therefore, lauded and acknowledged by the Ministry. As part of the multi-sectoral response led by the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ), we believe the input of the ZHCT project will strengthen community-based service delivery, an integral part of the response to HIV. The Ministry of Health and Child Care however, has noted the paucity of data on the cascade of HIV treatment and care services provided at community level and the ZHCT baseline and mapping assessment provides valuable baseline information which will be used to measure progress in this regard. -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital Hunyani Casembi Key Location Chikafa Chidodo Muzeza Musengezi Mine Mushumbi Musengezi Pools Chadereka Mission Mbire Mukumbura Place of Local Importance Hoya Kaitano Kamutsenzere Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Muzarabani Mavhuradonha Village Bakasa St. St. Gunganyama Pachanza Centenary Alberts Alberts Nembire Road Network Kazunga Chawarura Dotito Primary Chironga Rushinga Mount Rushinga Mukosa Guruve Karanda Rusambo Marymount Chimanda Secondary Marymount Shinje Darwin Rusambo Centenary Nyamatikiti Guruve Feeder azowe MashonalandMount M River Goromonzi Darwin Mudindo Dindi Kafura Bure Nyamanyora Railway Line Central Goora Kondo Madombwe Chistungo Mutepatepa Dendera Nyamapanda International Boundary Madziwa Borera Chiunye Kotwa Nyakudya Shinga Bradley Jester Mvurwi Madziwa Vanad Kasimbwi Institute Masarakufa Nzvimbo Madziwa Province Boundary Feock Mutawatawa Mudzi Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mudzi Mutorashanga Charewa Chikwizo Howard District Boundary Nyota Shamva Nyamatawa Gozi Institute Bindura Chindengu Kawere Muriel Katiyo Rwenya Freda & Mont Dor Caesar Nyamuzuwe River Mazowe Rebecca Uzumba Nyamuzuwe Katsande Makaha River Shamva Mudzonga Makosa Trojan Shamva Nyamakope Fambe Glendale BINDURA MarambaKarimbika Sutton Amandas Uzumba All Nakiwa Kapondoro Concession Manhenga Kanyongo Souls Great Muonwe Mutoko PfungweMuswe Dyke Mushimbo Chimsasa Lake/Waterbody Madamombe Jumbo Bosha Nyadiri Avila Makumbe Mutoko Jumbo Mazowe Makumbe Parirewa Nyawa Rutope Conservation Area -

Manicaland-Province

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Manicaland Buhera BANGURE ZVAVAHERA VILLAGE WARD 19 CHIEF NYASHANU BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera BETERA HEADMAN BETERA CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera BHEGEDHE BHEGEDHE VILLAGE CHIEF CHAMUTSA Secondary Manicaland Buhera BIKA KWARAMBA VILLAGE WARD 16 CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera BUHERA GAVA VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIEF MAKUMBE BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHABATA MUVANGIRWA VILLAGE WARD 29 Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHANGAMIRE MATSVAI VILLAGE WARD 32 NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAPANDUKA CHAPANDUKA VILLAGE CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAPWANYA CHAPWANYA HIGH SCHOOL WARD 2 BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAWATAMA CHAWATAMA VILLAGE WARD 31 CHIEF MAKUMBE Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIMBUDZI MATASVA VILLAGE WARD 32 CHIEF NYASHANU CHINHUWO VILLAGE CHIWENGA TOWNSHIP CHIEF Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHINHUWO NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIROZVA CHIROZVA VILLAGE Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIURWI CMAKUVISE VILLAGE WARD 32 Secondary Manicaland Buhera DEVULI NENDANDA VILLAGE CHIEF CHAMUTSA WARD 33 Secondary Manicaland Buhera GOSHO SOJINI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIEF MAKUMBE Secondary Manicaland Buhera GOTORA GOTORA VILLAGE WARD 22 CHIEF NYASHANU BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GUNDE MABARA VILLAGE WARD 9 CHIEF CHITSUNGE BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GUNURA CHIEF CHAMUTSA NEMUPANDA VILLAGE WARD 30 BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GWEBU GWEBU SECONDARY GWEBU VILLAGE Secondary Manicaland Buhera HANDE KARIMBA VILLAGE -

Drought and COVID-19 Response Update 18 Aug 2020

Drought and COVID-19 response update 18 Aug 2020 Key Highlights Total funding Number of children Number of children with Number of children 6-59 Number of caregivers of received – with SAM admitted for SAM successfully months who received children under 2 reached nutrition specific treatment treated Vitamin A with IYCF-e counselling 3.6K 19% 11,183 59% 6,254 45% 614,040 62% 952k 167% Background Operational presence Map Widespread economic shocks and the drought, have left over 1.1 million children and women in need of humanitarian nutrition assistance. Approximately 95,000 children under age 5 are suffering from acute malnutrition, with the national global acute malnutrition (GAM) prevalence at 3.6 percent (ZimVAC rural 2019). Pockets of increased cases of malnutrition particularly in Epworth and Gutu and Mutare districts remain a concern. The advent of COVID-19 and its restrictions had socio-economic negative impacts limiting access to nutritious foods by families. The Pandemic has also negatively impacted the supply and demand of essential Health and nutrition services. According to recent global estimates, these effects would translate into a 15 percent increase in acute malnutrition (14,250 children being malnourished in Partner presence Zimbabwe) resulting from increased food insecurity. Pellagra CERF funded cases have been on the rise in the country with double the cases being recorded from Jan to June 2020 as compared to Partner presence other the same time in 2019. funding sources Plans by partners to Nutrition response expand into these The nutrition response focused on groups that are most vulnerable to malnutrition, including pregnant and lactating No partners women, children under age 5, and people living with HIV in the 56 hardest-hit districts and three urban and peri-urban Response activities areas. -

Health Cluster Bulletin 11Ver2

Zimbabwe Health Cluster bulletin Bulletin No 11 1-15 April 2009 Highlights: Cholera outbreak situation update • About 96, 473 cases and 4,204 deaths, CFR 4.4% Following a 9 week decline trend in cholera cases, an upsurge was reported during epidemi- • Sustained decline of ological week 15. Batch reporting in three districts may have contributed to this slight in- the outbreak crease. • Cholera hotspots in The cumulative number of Mashonaland west, Cholera in Zimbabwe reported cholera cases was Harare and Chitungwiza 17 Aug 08 to 11th April 09 96, 473 and 4204 deaths with 10,000 cities cumulative Case Fatality Rate 8,000 Cases Deaths (CFR) as of 4.4 as of 15 April. During week 15, a 17% de- 6,000 crease in cases and 5% in- 4,000 crease in deaths was re- Number ported. The crude CFR is 2.7% 2,000 compared to 2.9% of week 14 0 while the I-CFR is 1.8% com- pared to 2.7% of week 14. The w2 w4 w6 w8 w36 w38 w40 w42 w44 w46 w48 w50 w52 w10 w12 w14 CFR has been steadily de- weeks clined although the proportion of deaths in health facilities has increased compared to Cholera in Zimbabw e from 16 Nov 08 to 11th A pril 09 those reported in the commu- W eekly c rude and institutional c ase-fatality ratios 10 nity. CFR 9 This is probably an indication Inside this issue: 8 iCFR 7 of more people accessing 6 treatment and/or the increas- Cholera situation 1 5 ing role of other co- 4 morbidities presenting along- ORPs in cholera 2 3 management percent side cholera. -

The Case of Action Faim Community Garden in Gutu, Ward 10, Zimbabwe

European Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 6 No. 6, 2018 ISSN 2056-5429 NON- GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: THE CASE OF ACTION FAIM COMMUNITY GARDEN IN GUTU, WARD 10, ZIMBABWE Cephas Chimire & Leonard Chitongo Department of Rural and Urban Development, Great Zimbabwe University, P.O. BOX 1235 Masvingo Zimbabwe Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Gutu rural area is hard hit by food insecurity that is partly caused by erratic rainfall received in the area. Thus adopting livelihood diversification strategies as either adaptive or coping mechanisms. The area has attracted humanitarian intervention in the form of Action Faim community garden in order to cushion the problem. The paper identifies the livelihoods brought by Action Faim. Data were obtained through the use of questionnaires, interviews, focus group discussions and observation. A sample of 30 respondents were randomly selected. Key informants were drawn from Gutu Rural District Council, Agritex Gutu and Action Faim. The researcher concluded that the community garden in Gutu Ward 10 has managed to reduce vulnerability and improved livelihood outcomes of beneficiaries. Despite the challenges of wild animal invasion, pest and diseases, poor markets, theft and financing. Therefore the researcher recommends increased capitalisation in research and extension services. Keywords: Non-Governmental Organisations, Sustainability, Development. INTRODUCTION Most if not all rural areas in Sub Saharan Africa are crippled with persistent food shortage (Chitongo, 2013a). According to World Bank (2000) 80% of people in rural areas of developing countries are currently facing food insecurity and are failing to cope with harsh climatic changes to secure their livelihoods. Climate change has rendered the environment not conducive for sustainable agriculture harvest, coupled with this is the governments’ inability to provide inputs, social welfare services and reduced commitment to rural development programs and projects (Makumbe, 1996). -

Manicaland Province

USAID Zimbabwe USAID RESEARCH TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE CENTER February 2020 Zimbabwe Stakeholder Mapping Report: Manicaland Province Dominica Chingarande and Prosper Matondi This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of contract no. 7200AA18C00057, which supports the Research Technical Assistance Center (RTAC). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of RTAC and NORC at the University of Chicago and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Month Year Acknowledgments The Research team expresses its gratitude to stakeholders participating in this study. Special appreciation to members of the District Food and Nutrition Committee and the District Drought Relief Committee, as well as to various nongovernmental organizations and private sector players who provided invaluable information about food security in Manicaland province. Research Technical Assistance Center The Research Technical Assistance Center is a network of academic researchers generating timely research for USAID to promote evidence-based policies and programs. The project is led by NORC at the University of Chicago in partnership with Arizona State University, Centro de Investigación de la Universidad del Pacífico (Lima, Peru), Davis Management Group, the DevLab@Duke University, Forum One, the Institute of International Education, the Pulte Institute for Global Development at the University of Notre Dame, Population Reference Bureau, the Resilient Africa Network at Makerere University (Kampala, Uganda), the United Negro College Fund, the University of Chicago, and the University of Illinois at Chicago. Suggested Citation Chingarande, D. and Matondi, P. 2020. Zimbabwe Stakeholder Mapping Report: Manicaland Province. -

Seismic Observation and Seismicity of Zimbabwe Mr

Seismic Observation and Seismicity of Zimbabwe Mr. Innocent Gibbon Tirivanhu MASUKWEDZA (2016 Global Seismology course) Meteorological Services Department of Zimbabwe 1. Introduction The Seismology section falls under the Meteorological Services Department of Zimbabwe. Currently, the department is functional under the Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate as a result of its main purpose being to contribute towards the safety of both life and property of Zimbabwe inhabitants. 2. Historical Background of Seismicity Measurements The need to monitor the seismicity of Zimbabwe came about by the construction of the Kariba dam as a way to monitor reservoir induced seismicity, but the idea was further expanded to include natural earthquakes. By then, the seismological station network composed of four analogue stations namely Bulawayo, Karoi, Mt Darwin and Chiredzi and these operated up to early 1990s. Although the dam construction began early in the 1950’s, seismograph stations were not deployed to monitor seismic activity until 1959, the year the dam was impounded. Since then, seismic activity in and around Zimbabwe has continuously been monitored. For the period 1959 to date, over 4,000 earthquakes in and around the country have been recorded. The largest earthquake recorded is that of magnitude 6.1 which occurred at Lake Kariba on September 23, 1963. The instruments to measure the seismicity of the country were issued to St George’s School (located in the city of Bulawayo) and later transferred to the Lawley Road site (situated in the same city) in 1903 with the arrival of Father Goetz. The main historical events after the arrival of Father Goetz are: 1950 – Dam wall construction of Lake Kariba and the sudden need for a seismological station.