Multi-Sector Programming at the Sub-National Level: a Case Study of Chipinge and Chiredzi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report

Conserving Our Land, Producing our Food – Sustainable Management of Land and Forests in Malawi & Zimbabwe “An evaluation of the Zimbabwe program component” FINAL REPORT Conservation Agriculture Farmer in Zvimba (Fieldwork Picture) Prepared by April 2015 “Conserving Our Land, Producing our Food – Sustainable Management of Land and Forests in Malawi & Zimbabwe” External Independent End of Term Evaluation Final Report – April 2015 DISCLAIMER This evaluation was commissioned by the Progressio / CIIR and independently executed by Taonabiz Consulting. The views and opinions expressed in this and other reports produced as part of this evaluation are those of the consultants and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Progressio, its implementing partner Environment Africa or its funder Big Lottery. The consultants take full responsibility for any errors and omissions which may be in this document. Evaluation Team Dr Chris Nyakanda / Agroforestry Expert Mr Tawanda Mutyambizi / Agribusiness Expert P a g e | i “Conserving Our Land, Producing our Food – Sustainable Management of Land and Forests in Malawi & Zimbabwe” External Independent End of Term Evaluation Final Report – April 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS On behalf of the Taonabiz consulting team, I wish to extend my gratitude to all the people who have made this report possible. First and foremost, I am grateful to the Progressio and Environment Africa staff for their kind cooperation in providing information as well as arranging meetings for field visits and national level consultations. Special thanks go to Patisiwe Zaba the Progressio Programme Officer and Dereck Nyamhunga Environment Africa M&E Officer for scheduling interviews. We are particularly indebted to the officials from the Local Government Authorities, AGRITEX, EMA, Forestry Commission and District Councils who made themselves readily available for discussion and shared their insightful views on the project. -

Mashonaland Central Province Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (Zimvac) 2020 Rural Livelihoods Assessment Report Foreword

Mashonaland Central Province Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) 2020 Rural Livelihoods Assessment Report Foreword The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) under the coordination of the Food and Nutrition Council, successfully undertook the 2020 Rural Livelihoods Assessment (RLA), the 20th since its inception. ZimVAC is a technical advisory committee comprised of representatives from Government, Development Partners, UN, NGOs, Technical Agencies and the Academia. In its endeavour to ‘promote and ensure adequate food and nutrition security for all people at all times’, the Government of Zimbabwe has continued to exhibit its commitment for reducing food and nutrition insecurity, poverty and improving livelihoods amongst the vulnerable populations in Zimbabwe through operationalization of Commitment 6 of the Food and Nutrition Security Policy (FNSP). As the country is grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, this assessment was undertaken at an opportune time as there was an increasing need to urgently collect up to date food and nutrition security data to effectively support the planning and implementation of actions in a timely and responsive manner. The findings from the RLA will also go a long way in providing local insights into the full impact of the Corona virus on food and nutrition security in this country as the spread of the virus continues to evolve differently by continent and by country. In addition, the data will be of great use to Government, development partners, programme planners and communities in the recovery from the pandemic, providing timely information and helping monitor, prepare for, and respond to COVID-19 and any similar future pandemics. Thematic areas covered in this report include the following: education, food and income sources, income levels, expenditure patterns and food security, COVID-19 and gender based violence, among other issues. -

Assessment of the Zimbabwe Assistance Program in Malaria April 2020

Assessment of the Zimbabwe Assistance Program in Malaria April 2020 Assessment of the Zimbabwe Assistance Program in Malaria April 2020 This publication was produced with the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of the Data for Impact Data for Impact (D4I) associate award University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 7200AA18LA00008, which is implemented by 123 West Franklin Street, Suite 330 the Carolina Population Center at the Chapel Hill, NC 27516 USA University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in Phone: 919-445-9350 | Fax: 919-445-9353 [email protected] partnership with Palladium International, LLC; http://www.data4impactproject.org ICF Macro, Inc.; John Snow, Inc.; and Tulane University. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. TRE-20-29 D4I ISBN 978-1-64232 -258 -3 Assessment of the Zimbabwe Assistance Program in Malaria 2 Acknowledgments This assessment was undertaken by Data for Impact (D4I), funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), in collaboration with the Zimbabwe National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) and the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI)/Zimbabwe. The following people were involved in the assessment: Agneta Mbithi, Yazoumé Yé, Andrew Andrada, Cristina de la Torre, Logan Stuck, Joshua Yukich, Erin Luben, and Jessica Fehringer (D4I); and Brian Maguranyanga and Jaqueline Kabongo (M-Consulting Group). The assessment team thanks the people who generously shared their time, experiences, and ideas for the assessment, including the NMCP, led by its director, Dr. Joseph Mberikunashe; the provincial, district, and facility teams; the Zimbabwe Assistance Program in Malaria team; malaria implementing partners (IPs); and the outpatient and antenatal care patients at the health facilities visited. -

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

Promotion of Climate-Resilient Lifestyles Among Rural Families in Gutu

Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts | Zimbabwe Sahara and Sahel Observatory 26 November 2019 Promotion of climate-resilient lifestyles among rural families in Gutu Project/Programme title: (Masvingo Province), Mutasa (Manicaland Province) and Shamva (Mashonaland Central Province) Districts Country(ies): Zimbabwe National Designated Climate Change Management Department, Ministry of Authority(ies) (NDA): Environment, Water and Climate Development Aid from People to People in Zimbabwe (DAPP Executing Entities: Zimbabwe) Accredited Entity(ies) (AE): Sahara and Sahel Observatory Date of first submission/ 7/19/2019 V.1 version number: Date of current submission/ 11/26/2019 V.2 version number A. Project / Programme Information (max. 1 page) ☒ Project ☒ Public sector A.2. Public or A.1. Project or programme A.3 RFP Not applicable private sector ☐ Programme ☐ Private sector Mitigation: Reduced emissions from: ☐ Energy access and power generation: 0% ☐ Low emission transport: 0% ☐ Buildings, cities and industries and appliances: 0% A.4. Indicate the result ☒ Forestry and land use: 25% areas for the project/programme Adaptation: Increased resilience of: ☒ Most vulnerable people and communities: 25% ☒ Health and well-being, and food and water security: 25% ☐ Infrastructure and built environment: 0% ☒ Ecosystem and ecosystem services: 25% A.5.1. Estimated mitigation impact 399,223 tCO2eq (tCO2eq over project lifespan) A.5.2. Estimated adaptation impact 12,000 direct beneficiaries (number of direct beneficiaries) A.5. Impact potential A.5.3. Estimated adaptation impact 40,000 indirect beneficiaries (number of indirect beneficiaries) A.5.4. Estimated adaptation impact 0.28% of the country’s total population (% of total population) A.6. -

Crop Area, Condition and Stage

Foreword The Government of Zimbabwe has continued to exhibit its commitment for reducing food and nutrition insecurity in Zimbabwe. Evidence include the culmination of ZimASSET’s Food and Nutrition Security Cluster and the multi-sector Food and Nutrition Security Policy (FNSP). Recognising the vagaries of climate variabilities and the unforeseeable potential livelihood challenges, Government put in place structures whose mandates are, among other things to provide early warning information for early actioning. The Food and Nutrition Council, through the ZimVAC, is one of such structures which strives to fulfil the aspirations of the FNSP’s commitment number 6 of providing food and nutrition early warning information. In response to the advent of the El Nino phenomena which has resulted in the country experiencing long dry spells, the ZimVAC undertook a rapid assessment focussing on updating the ZimVAC May 2015 results. The lean season monitoring focused on the relevant food and nutrition security parameters. The process followed a 3 pronged approach which were, a review of existing food and nutrition secondary data, qualitative district Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and for other variables a quantitative household survey which in most cases are representative at provincial and national level. This report provides a summation of the results for the 3 processes undertaken and focuses on the following thematic areas: the rainfall season quality, 2015/16 agricultural assistance, crop and livestock condition, food and livestock markets, gender based violence, household income sources and livelihoods strategies, domestic and production water situation, health and nutrition, food assistance and a review of the rural food security projections. -

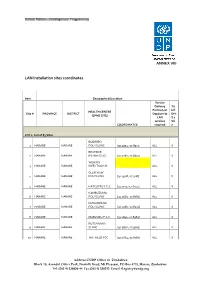

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

TREATMENT SITES Southern Africa HIV and AIDS Information LISTED by PROVINCE and AREA Dissemination Service

ARV TREATMENT SITES Southern Africa HIV and AIDS Information LISTED BY PROVINCE AND AREA Dissemination Service MASVINGO · Bulilima: Plumtree District hospital: · Bikita: Silveira Mission Hospital: Tel: (038)324 Tel. (019) 2291; 2661-3 · Chiredzi: Hippo Valley Estates Clinic: · Gwanda: Gwanda OI Clinic: Tel: (084)22661-3: Tel: (031)2264 - Mangwe: St. Annes Brunapeg: · Chiredzi: Colin Saunders Hosp. Tel: (082) 361/466 AN HIV/AIDS Tel: (033)6387:6255 · Kezi-Matobo: Tshelanyemba Mission Hosp: · Chiredzi: Chiredzi District Hosp.: Tel: (033) Tel: (082) 254 · Gutu: Gutu Mission Hosp: · Maphisa District Hosp: Tel. (082) 244 Tel: (030)2323:2313:2631:3229 · Masvingo: Morgenster Mission Hosp: MIDLANDS Tel: (039)262123 · Chivhu General Hosp: Tel: (056):2644:2351 TREATMENT - Masvingo Provincial Hosp: · Chirumhanzu: Muvonde Hosp: Tel: (032)346 Tel: (039)263358/9; 263360 · Mvuma: St Theresas Mission Hosp: - Masvingo: Mukurira Memorial Private Hospital: Tel: (0308)208/373 Tel. (039) 264919 · Gweru: Gweru Provincial Hospital: ROADMAP FOR · Mwenezi: Matibi Mission Hospital: Tel. (0517) 323 Tel: (054) 221301:221108 · Zaka: Musiso Mission Hosp: · Gweru: Gweru City Hospital: Tel: (054) Tel: (034)2286:2322:2327/8 221301:221108 - Gweru: Mkoba 1 Polyclinic, Tel. MATEBELELAND NORTH - Gweru: Lower Gweru Rural Health Clinic: · Hwange: St Patricks Mission Hosp: Tel: (054) 227023 Tel: (081)34316-7 · Kwekwe: Kwekwe General Hospital: ZIMBABWE · Lupane: St Lukes Mission Hosp: Tel: (055)22333/7:24828/31 Tel: (0898)362:549:349 · Mberengwa: Mnene Mission Hospital: · Tsholotsho: Tsholotsho District Hosp: Tel. (0518) 352/3 Tel: (0878) 397/216/299 A guide for accessing anti- PRIVATE DOCTORS retroviral treatment in MATEBELELAND SOUTH For a list of private doctors who have special Zimbabwe: what it is, where · Beitbridge: Beitbridge District Hosp: training in ARV treatment and counselling, ask Tel.(086) 22496-8 your own doctor or contact SAfAIDS. -

“Operation Murambatsvina”

AN IN -DEPTH STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF OPERATION MUR AMBATSVINA/RESTORE ORDER IN ZIMBABWE “Primum non Nocere”: The traumatic consequences of “Operation Murambatsvina”. ActionAid International in collaboration with the Counselling Services Unit (CSU), Combined Harare Residents’ Association (CHRA) and the Zimbabwe Peace Project (ZPP) Novemberi 2005 PREFACE The right to govern is premised upon the duty to protect the governed: governments are elected to provide for the security of their citizens, that is, to promote and protect the physical and livelihood security of their citizens. In return for such security the citizens agree to surrender the powers to govern themselves by electing representatives to govern them. This is the moral contract between those who govern and those who are governed. For any government to knowingly and deliberately undermine the security of its citizens is a breach of this contract and the principle of democracy. Indeed, it removes the very foundation upon which the legitimacy of government is based. Just as there is an injunction upon health workers not to harm their patients - ‘primum non nocere”, “first do no harm” - so there must be an injunction upon governments that they ensure that any action that they take or policy that they implement will not be harmful. This is the very reason why there was formed in 2001 the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty of the United Nations promulgating the “Responsibility to Protect”: States have an obligation to protect their citizens, and the international community has an obligation to intervene when it is evident that a state cannot or will not protect its people. -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland Central Karanda Chimandau Guruve MukosaMukosa Guruve Kamusasa Karanda Marymount Matsvitsi Marymount Mary Mount Locations ShinjeShinje Horseshoe Nyamahobobo Ruyamuro RUSHINGA CentenaryDavid Nelson Nyamatikiti Nyamatikiti Province Capital Nyakapupu M a z o w e CENTENARY Mazowe St. Pius MOUNT DARWIN 2 Chipuriro Mount DarwinZRP NyanzouNyanzou Mt Darwin Chidikamwedzi Town 17 GoromonziNyahuku Tsakare GURUVE Jingamvura MAKONDE Kafura Nyamhondoro Place of Local Importance Bepura 40 Kafura Mugarakamwe Mudindo Nyamanyora Chingamuka Bure Katanya Nyamanyora Bare Chihuri Dindi ARDA Sisi Manga Dindi Goora Mission M u s e n g e z i Nyakasoro KondoKondo Zvomanyanga Goora Wa l t o n Chinehasha Madziwa Chitsungo Mine Silverside Donje Madombwe Mutepatepa Nyamaruro C o w l e y Chistungo Chisvo DenderaDendera Nyamapanda Birkdale Chimukoko Nyamapanda Chindunduma 13 Mukodzongi UMFURUDZI SAFARI AREA Madziwa Chiunye KotwaKotwa 16 Chiunye Shinga Health Facility Nyakudya UZUMBA MARAMBA PFUNGWE Shinga Kotwa Nyakudya Bradley Institute Borera Kapotesa Shopo ChakondaTakawira MvurwiMvurwi Makope Raffingora Jester H y d e Maramba Ayrshire Madziwa Raffingora Mvurwi Farm Health Scheme Nyamaropa MUDZI Kasimbwi Masarakufa Boundaries Rusununguko Madziva Mine Madziwa Vanad R u y a Madziwa Masarakufa Shutu Nyamukoho P e m b i Nzvimbo M u f u r u d z i Madziva Teacher's College Vanad Nzvimbo Chidembo SHAMVA Masenda National Boundary Feock MutawatawaMutawatawa Mudzi Rosa Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mutorashanga Madimutsa Chiwarira -

February 2011

Zimbabwe Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin Number 102 Epidemiological week 10 (week ending 13 March) March 2011 Highlights Malaria outbreaks in Kadoma and Makoni Figure 1: Cumulative Cholera Cases since 1 January 2011 Cholera cases reported in Chiredzi Contents Chipinge 133 A. General context Mutare 86 B. Epidemic prone diseases C. Events of public health concern in the region Buhera 66 D. Preparedness Chiredzi E. Timeliness and completeness of data 42 F. Recommendations for action/follow up Bikita 42 Annex 1: National summary of cases/deaths by condition District Murewa 5 by week Annex 2: Standard case definitions and alert/action Chimanimani 4 epidemic thresholds Kadoma 2 Mutasa 1 A. General context 0 50 100 150 Cholera cases Cholera continues to be reported in week 10 of 2011, having spilled over from 2010. Since week 45 of Figure 2: Zimbabwe Cholera Epicurve, Week 5, 2010 to Week 10, 2011 2010, no new outbreaks of measles have been reported, although the situation is being closely 200 monitored. We are amidst the malaria season and 180 malaria outbreaks are now being reported. Within the C 160 region, suspected Rift Valley fever has been reported h 140C in South Africa. o 120a l 100s B. Epidemic prone diseases e e80 r 60s Cholera 40 a 20 Nine out of the 62 districts, namely: Bikita, Buhera, 0 17 33 5 9 13 21 25 29 37 41 45 49 1 5 9 Chimanimani, Chipinge, Chiredzi, Kadoma,Murewa, 1 Mutare and Mutasa have reported cases since the start of 2011. There were 381 cumulative cases: 324 2010 2011 suspected cases, 57 laboratory confirmed cases and 7 Epidemiological Week Number by year th deaths reported by the 13 March 2011.