A Teacher's Resource Guide to Galapagos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galapagos Islands Fact Sheet Galapagos Islands Fact Sheet

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS FACT SHEET GALAPAGOS ISLANDS FACT SHEET INTRODUCTION The Galapagos Islands are located west of Ecuador and are renowned for being the home to a vast array of fascinating species of wildlife, including lava lizards, the giant tortoise as well as red and blue-footed boobies. They are one of the world’s foremost destinations for wildlife viewing, many of the plant and animal species being found nowhere else in the world. Located at the confluence of three ocean currents and surrounded by a marine reserve, the islands abound with marine species. The Galapagos Islands, of which there are 19 main islands, are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Pacific Ocean. They lay either side of the Equator and 1,000km west of the South American continent and mainland Ecuador of which they are a part. The islands were formed as a result of processes caused by volcanic and seismic activity. These processes along with the isolation of the islands resulted in the development of unusual animal life. Charles Darwin’s visit to the islands in 1835 was the inspiration for his theory of evolution by natural selection. The largest island Isabela, measures 5,827 square kilometres and accounts for nearly three quarters of the total land area of the Galapagos. Volcan Wolf on Isabela is the highest point of the Galapagos at 1,707m above sea level. GALAPAGOS ISLANDS FACT SHEET CLIMATE The Galapagos Islands have a subtropical and dry climate with comfortable temperatures year-round. The warmest months are usually from December to June (high season) and this is the recommended time to visit. -

Galapagos News

GALAPAGOS NEWS Fall-Winter 2015 NEW GIANT Flamingo Origins TORTOISE Disappearing SPECIES Opuntia Cacti NAMED! PROJECT UPDATES: Tortoises on Santa Fe Plans for Tortoises in 2016 Education for Sustainability PHOTOGRAPHING GALAPAGOS PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS! GALAPAGOS GIFTS ON SALE: GALAPAGOS CALENDAR 2016 www.galapagos.org Johannah Barry and a Galapagos National Park ranger, Freddy Villalva, watch feeding time for baby tortoises that reside at the Tortoise Center on Santa Cruz. © Ros Cameron, Galapagos Conservancy FROM THE PRESIDENT Johannah Barry CONTENTS nce again, we are delighted to share big news about big tortoises! With support from 3 GC Membership OGalapagos Conservancy, our colleagues at Yale University have embarked on an Galapagos Guardians ambitious program of genetic testing and identification of previously unidentified Galapagos 4-5 Galapagos News tortoises. That painstaking work was rewarded with the discovery of a new species of 6-7 The Mystery of the Galapagos tortoise — the Eastern Santa Cruz tortoise. Dr. Gisella Caccone, the study’s senior Disappearing Opuntia author, named the tortoise Chelonoidis donfaustoi after Fausto Llerena Sanchez, or "Don 8-9 In the Pink: Flamingos Fausto" as he is known by his friends. His 43-year history as a Galapagos National Park ranger 10-11 A Photographer's View also included a long relationship with Lonesome George as his primary keeper. This naming honors Don Fausto and celebrates the important work of the keepers and Park rangers whose from the Crater Rim work is indispensable to protecting and preserving Galapagos. 12-13 Galapagos Updates: We are pleased to highlight the work of long-time Galapagos scientists, Frank Sulloway Photo Contest, Desktop and Bob Tindle, whose seminal work on cactus ecology and flamingo population health have Wallpaper, SETECI, BBB spanned four decades. -

Darwin's Galapagos Islands

DARWIN’S GALAPAGOS ISLANDS THE FLORA & FAUNA OF ECUADOR MARCH 12 TH - 22 ND, 2019 $5,915 LAND COST* The Minnesota Landscape Arboretum in conjunction with Knowmad Adventures is proud to announce an incredible Ecuador & Galapagos experience: “Darwin’s Galapagos Islands and Flora and Fauna of Ecuador.” This 11-day trip from March 12th to 22nd will highlight the spectacular gardens and diverse ecosystems of mainland Ecuador and includes a luxurious 5-day cruise around Darwin’s Galapagos Islands, which are full of fascinating endemic species and beautiful volcanic landscapes. Join Director of Operations of the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, Alan Branhagen, along with excellent local and naturalist guides on this once-in-a-lifetime adventure. Have unique cultural interactions, explore the cloud forest’s plants, orchids and over 132 hummingbird species, stand amongst giant tortoises, colonies of iguanas, blue-footed boobies and much more! Call Knowmad Adventures at 612.315.2894 (ext. 105 for Renee) for more information and to register. This trip will likely sell out and space is limited. HIGHLIGHTS OF THE TRIP • Cruise the Galapagos Islands aboard a luxury class boat with less than 100 passengers • Enjoy expert naturalist-led excursions to discover myriad of endemic species, spectacular wildlife with no fear of humans, and unique landscapes • Walk through palo santo forests full of iguanas; explore the most pristine of the Galapagos Islands, Fernandina island, where you’ll fnd the lava cactus; visit the Charles Darwin Research station where -

WILDLIFE CHECKLIST Reptiles the Twenty-Two Species of Galapagos

WILDLIFE CHECKLIST Reptiles The twenty-two species of Galapagos reptiles belong to five families, tortoises, marine turtles, lizards/iguanas, geckos and Clasifications snakes. Twenty of these species are endemic to the * = Endemic archipelago and many are endemic to individual islands. The Islands are well-known for their giant tortoises ever since their R = Resident discovery and play an important role in the development of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. The name "Galapagos" M = Migrant originates from the spanish word "galapago" that means saddle. * Santa Fe land Iguana Conolophus pallidus Iguana Terrestre de Santa Fe * Giant Tortoise (11 Geochelone elephantopus Tortuga Gigante subspecies) M Pacific Green Sea Chelonia mydas Tortuga Marina Turtle * Marine Iguana * (7 Amblyrhynchus cristatus Iguana Marina subspecies) * Galapagos land Conolophus subcristatus Iguana Terrestre Iguana * Lava lizard (7 species) Tropidurus spp Lagartija de Lava Phyllodactylus * Gecko (6 species) Gecko galapagoensis * Galapagos snake (3 Culebras de Colubridae alsophis species) Galapagos Sea Birds The Galapagos archipelago is surrounded by thousands of miles of open ocean which provide seabirds with a prominent place in the fauna of the Islands . There are 19 resident species (5 are endemic), most of which are seen by visitors. There may be as many as 750,000 seabirds in Galapagos, including 30% of the world's blue-footed boobies, the world's largest red- footed booby colony and perhaps the largest concentration of masked boobies in the world (Harris, -

Lüttge-2010-Ability of Crassulacean Acid Metabolism Plants to Overcome

AoB PLANTS http://aobplants.oxfordjournals.org/ Open access – Review Ability of crassulacean acid metabolism plants to overcome interacting stresses in tropical environments Ulrich Lu¨ttge* Institute of Botany, Technical University of Darmstadt, Schnittspahnstrasse 3-5, D-64287 Darmstadt, Germany Received: 26 January 2010; Returned for revision: 16 March 2010; Accepted: 10 May 2010; Published: 13 May 2010 Citation details:Lu¨ttge U. 2010. Ability of crassulacean acid metabolism plants to overcome interacting stresses in tropical environments. AoB PLANTS 2010: plq005, doi:10.1093/aobpla/plq005 Abstract Background and Single stressors such as scarcity of waterand extreme temperatures dominate the struggle for life aims in severely dry desert ecosystems orcold polar regions and at high elevations. In contrast, stress in the tropics typically arises from a dynamic network of interacting stressors, such as availability of water, CO2, light and nutrients, temperature and salinity. This requires more plastic spatio- temporal responsiveness and versatility in the acquisition and defence of ecological niches. Crassulacean acid The mode of photosynthesis of crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) is described and its flex- metabolism ible expression endows plants with powerful strategies for both acclimation and adaptation. Thus, CAM plants are able to inhabit many diverse habitats in the tropics and are not, as com- monly thought, successful predominantly in dry, high-insolation habitats. Tropical CAM Typical tropical CAM habitats or ecosystems include exposed lava fields, rock outcrops of insel- habitats bergs, salinas, savannas, restingas, high-altitude pa´ramos, dry forests and moist forests. Morphotypical and Morphotypical and physiotypical plasticity of CAM phenotypes allow a wide ecophysiological physiotypical amplitude of niche occupation in the tropics. -

The Systematics and Genetics of Tomatoes on the Galápagos Islands (Solanum, Solanaceae)

The systematics and genetics of tomatoes on the Galápagos Islands (Solanum, Solanaceae) By Sarah Catherine Darwin A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at University College London August 2009 Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment University College London 1 Declaration I, Sarah Darwin confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Chapter 2 is a reprint from a paper on the taxonomy of the tomatoes of the Galápagos Islands published in Systematics and Biodiversity in 2003. This was a collaborative project, and the authors were Sarah Darwin, Sandra Knapp and Iris Peralta. I was the lead author as this was part of my thesis work, and I carried out most of the work towards the paper. Below I list the contributions of each author for Chapter 2. Morphological analysis I undertook the analysis of the herbarium specimens, with particular guidance from Sandy Knapp and Iris Peralta for the S. lycopersicum and S. pimpinellifolium collected from the mainland of South America. Morphometrics Morphological characters were selected by all of us based on my experience from fieldwork, Dr Peralta’s experience from greenhouse grown accessions and Dr Knapp’s experience from herbarium specimens. I undertook the measurement of the living plants and herbarium specimens with the assistance/guidance of Drs Peralta and Knapp Statistics I and Dr Peralta undertook the PCA, with advice from Drs Claudio Galmarini and Clive Moncrieff. Taxonomic treatment Dr Knapp and Dr Norman Robson wrote the Latin for the taxonomic treatment. -

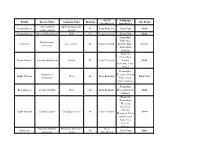

Family Species Name Common Name Endemic IUCN Classification Galapagos Distribution Life Form Amaranthaceae Alternanthera Echinoc

IUCN Galapagos Family Species Name Common Name Endemic Life Form Classification Distribution Alternanthera Spiny-headed chaff Amaranthaceae Yes Data Deficient Santa Cruz Shrub echinocephala flower Amaranthaceae Alternanthera filifolia N/A Yes Least Concern Santa Cruz Shrub Femandina, Genovesa, Brachycereus Cactaceae Lava cactus Yes Least Concern Isabela, Pinta, Cactus nesioticus Santa Cruz, Santiago Espanola, Fernandina, Simaroubaceae Castela galapageia Castela Yes Least Concern Isabela, Shrub Marchena, Pinta, Pinzon Fernandina, Chamaesyce Floreana, Isabela, Euphorbiaceae N/A Yes Data Deficient Small Tree galapageia Pinta, Santa Cruz, Santiago Fernardina, Boraginaceae Cordia resoluta N/A Yes Data Deficient Floreana Isabela, Shrub Santiago Espanola, Fernandina, Floreana, Genovesa, Isabela, Euphorbiaceae Croton scouleri Galápagos croton Yes Least Concern Shrub Marchena, Pinta, San Cristobal, Santa Cruz, Santa Fe, Santiago Darwiniothamnus Thin leafed Darwin's Near Asteraceae Yes Santa Cruz Shrub tenuifolius shrub Threathened Gossypium Floreana, Isabela, Malvaceae Juss. barbadense var. N/A Yes Least Concern San Cristobal, Shrub darwinii Santa Cruz Espanola, Fernandina, Floreana, Isabela, Malvaceae Gossypium darwinii Darwin's cotton Yes Least Concern Marchena, Pinta, Shrub Pinzon, San Cristobal, Santa Cruz, Santiago Espanola, Floreana, Genovesa, Convolvulaceae Ipomoea habeliana Lava morning glory Yes Least Concern Isabela, Plant Marchena, Pinta, Pinzon, Santa Cruz, Santiago Floreana, Isabela, Jasminocereus Cactaceae Candelabra cactus Yes Least Concern -

Gálapagos Islands and Darwin's Theory of Evolution

GENERAL ARTICLE Gálapagos Islands and Darwin’s Theory of Evolution K R Shivanna The Gálapagos Islands are closely associated with Darwin’s name because the animals and plants living on these islands provided clues to Darwin to formulate his theory of evolution by means of natural selection. Gálapagos is a group of 19 vol- canic, Pacific islands on the equator, about 1000 km west of Ecuador of South America. Being volcanic, there was no life on them when they were formed; all organisms presently liv- ing on the islands are the descendants of those that came from the South American mainland. Darwin visited these islands K R Shivanna after retiring in 1835 during his voyage around the world in HMS Beagle from the Department of and stayed for five weeks, studying and collecting plants, ani- Botany, University of Delhi, mals, and rock samples from the islands. His detailed studies has been associated with of the collections upon his return to London, particularly on Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the tortoises, mockingbirds, and finches, revealed that all these Environment, Bengaluru as species living on the Gálapagos were endemic to the island INSA Honorary Scientist. His anddidnotoccuranywhereelseintheworld,butallofthem major interests are the closely resembled the species present on the South Ameri- structural and functional aspects of reproductive can mainland. This realization made him speculate that the biology of flowering plants. Gálapagos inhabitants, after they arrived from the mainland, evolved into different species over the years, shaped by the en- vironment of the islands. He visualized evolutionary changes as a result of the competition amongst individuals under chan- ged environmental conditions, which acted as a selective agent. -

Wildlife Travel Galapagos 2019

WILDLIFE TRAVEL Galapagos 2019 Galapagos & Ecuador, 13th to 26th March 2019, Trip Report Leader Philip Precey Wildlife Travel [email protected] # DATE LOCATIONS & NOTES 1 13th Travel. Arrive in Guayaquil 2 14th Cerro Blanco and Parque Lago 3 15th Guayaquil to Baltra. North Seymour zodiac cruise. 4 16th Sullivan Bay (Santiago) and Rabida 5 17th Punta Espinosa (Fernandina) and Elizabeth Bay (Isabela) 6 18th Isabela: Urbina Bay and Tagus Cove 7 19th Puerto Egas (Santiago) and Bartholome 8 20th Sombrero Chino and Cerro Dragon (Sta Cruz) 9 21st Santa Cruz: Los Gemelos, Manzanillo Ranch, Charles Darwin Research Station, Puerto Ayora 10 22nd North Seymour and Puerto Ayora 11 23rd Santa Cruz: Manzanillo Ranch and German Bay 12 24th flight back to Guayaquil 13 25th Guayaquil city tour: Iguana Park, Malecon and Santa Ana hill Flight back to Europe 14 26th Amsterdam and return to UK A galley of some of Philip’s photos from this trip can be seen on our Flickr site, at www.flickr.com/photos/wildlifetravel/albums/72157704276740232 An (ever-evolving) collection of photos from all Philip’s previous visits to the islands can be seen at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/wildlifetravel/collections/72157704276768482/ 2 Galapagos & Ecuador, 13th to 26th March 2019, Trip Report DIARY 14th March: Cerro Blanco and Parque Lago We spent our first Ecuadorean day in the company of Daniel and Fernando, who took us first into the dry forest at Cerro Blanco, where we enjoyed some colourful butterflies and a sleepy sloth alongside the introduction to the Tumbesian birdlife, and then to the Water Hyacinth-covered reservoir at Parque Lago, with its Snail Kites and noisy Limpkins. -

Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands

Ecuador and The Galapagos Islands Naturetrek Tour Report 10th – 29th February 2020 Nazca Booby Magnificent Frigatebird Compiled by Jane Collins, Siobhan Dawson and Dawn Thomas Photos courtesy of Colin Brown, Mike Jones, Alex Lewicka and David Rowe . Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Ecuador and The Galapagos Islands Day 1 Monday 10th February Up early for flight to Amsterdam. 1.5 hrs on the tarmac due to storm Ciara, just caught flight to Quito which was held for us. Long flight but uneventful. We were met at Quito airport by Raoul and also our fellow travellers (15 in all) and were taken to our Hotel Mercure Almada. Day 2 Tuesday 11th February Quito Met at 09.00 and had city tour of ‘old’ Quito which was very interesting. The old style colonial buildings and the gargoyles on the cathedral, all Galapagos fauna, were the highlight. Inside, the stained-glass windows were beautiful. Also stunning was La Iglesias de la Compania de Jesus, the Gold Church, with a baroque interior. Went up the hill to the statue of the virgin standing on a dragon, overlooking Quito. The view is amazing, with the old Inca capital city and the new town beyond, surrounded by several active snow-capped volcanoes, including Cotopaxi. Some of the group went back to the hotel, while the rest of us walked to the Botanic Gardens. We stopped at a cafe for lunch by the garden entrance. -

Galapagos Educator Guide

Teacher’s Resource Guide Teacher’s Resource Guide to Acknowledgments A Teacher’s Resource Guide to Galapagos was cre SCIENCE AND CURRICULUM ADVISORS: ated by the National Science Teachers Dr. Carole Baldwin, Smithsonian Institution, Association, Special Publications, 1840 Wilson Washington, DC Blvd., Arlington, VA 22201-3000, with funding Sue Cassidy, Bishop McNamara High School, generously provided by the National Science Forestville, MD Foundation and the Smithsonian Institution. Dr. Robert Hoffmann, Smithsonian Institution, This material copyright © 2000 Smithsonian Washington, DC Institution and Imax Ltd. All rights reserved. Sue Mander, Imax Ltd., Toronto, Canada IMAX® and AN IMAX EXPERIENCE® are registered trademarks of Imax Corporation. Laura McKie, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC WRITER: Richard Benz, Wickliffe High School, Dr. David Pawson, Smithsonian Institution, Wickliffe, OH Washington, DC EDITOR: Erin Miller, National Science Teachers Sharon Radford, Paideia School, Atlanta, GA Association Dr. Irwin Slesnick, Western Washington DIRECTOR OF SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS: University, Bellingham, WA Shirley Watt Ireton, National Science Teachers Dr. John Weld, Oklahoma State University, Association Stillwater, OK Dr. Don Wilson, Smithsonian Institution, Table of Contents Washington, DC Sponsored by America Online Inc., the Introduction for Teachers . 3 Smithsonian Institution and Imax Ltd. present in Film Synopsis . 3 association with the National Science Foundation, Pre-Screening Discussion . 3 a Mandalay Media Arts production Galapagos. Where in the World? . 4 Adventuring in the Archipelago . 5 EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS: Laurence P. Adventuring in Your Own Backyard . 8 O’Reilly, Andrew Gellis, Peter Guber, Barry Clark How Did Life Get to the Galápagos? . 10 PRODUCERS/DIRECTORS: Al Giddings and Current Events in the Ocean . 11 David Clark Hot Side Hot, Cool Side Cool . -

Ecuador & the Galapagos Islands

Ecuador & The Galapagos Islands Naturetrek Tour Report 30 July - 21 August 2007 Galapagos Sea-lion and pup Crossing equator Land Iguana Lava Heron Report Compiled by Jenny Willsher Photographs by John Willsher Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Ecuador & The Galapagos Islands Tour leaders: Juan Manuel Salcedo (local guide) Jenny Willsher (Naturetrek) Participants: Marie Dodson Pauline Francis Hugh Tottle Susan Littlewood Graeme and Anne Robertson Bill Spurrell Jenna Spurrell Roger and Pauline Bingham John and Jan Jones Bren Robson John Willsher “Cachalote” crew: Hose – Captain Richard – Barman and waiter Pedro – Cook Pedro – Engineer Jimmy – Helmsman Danny – Helmsman Mainland personnel: Gloria and Esteban Gustavo Canas Marcelo Andy If there was ever a place where one runs out of superlatives, this is it! The uniqueness of the wildlife is one thing but the opportunity to get up close and personal to most of it just takes your breath away. From sea lion pups snuffling at your feet, Blue-footed Booby chicks, balls of white fluff, looking up at you from their grubby nests on the ground, the courtship ritual of the Waved Albatross, or a pair of Humpback Whales, Great and Magnificent Frigate Birds in mixed groups puffing up their bright red throat patches, to amazing aerial displays from these sky pirates, the Galapagos Islands did not disappoint. The intriguing diversity and the magic of ‘adaptive radiation’ of many of the islands flora and fauna, kept us attentive and fascinated, in large part due to the knowledge, passion and dedication of our local naturalist, Juan Manuel Salcedo.