Pressiqn Ist Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BROWNIE the Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet

BROWNIE The Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet Dan Morgenstern Grammy Award for Best Album Notes 1990 Disc 1 1. DELILAH 8:04 Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: (V. Young) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 2. DARN THAT DREAM 4:02 Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (De Lange - V. Heusen) (ds) 3. PARISIAN THOROUGHFARE 7:16 (B. Powell) 4. JORDU 7:43 (D. Jordan) 5. SWEET CLIFFORD 6:40 (C. Brown) 6. SWEET CLIFFORD (CLIFFORD’S FANTASY)* 1:45 1~3: Los Angeles, August 2, 1954 (C. Brown) 7. I DON’T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANCE* 3:03 4~8: Los Angeles, August 3, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 8. I DON’ T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANC E 7:19 9~12: Los Angeles, August 5, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 9. STOMPIN’ AT TH E SAVOY 6:24 (Goodman - Sampson - Razaf - Webb) 10. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 7:36 (C. Porter) 11. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* 8:29 * Previously released alternate take (C. Porter) 12. I’ LL STRING ALONG WITH YOU 4:10 (Warren - Dubin) Disc 2 1. JOY SPRING* 6:44 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: 2. JOY SPRING 6:49 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 3. MILDAMA* 3:33 (M. Roach) Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (ds) 4. MILDAMA* 3:22 (M. Roach) Los Angeles, August 6, 1954 5. MILDAMA* 3:55 (M. Roach) 6. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

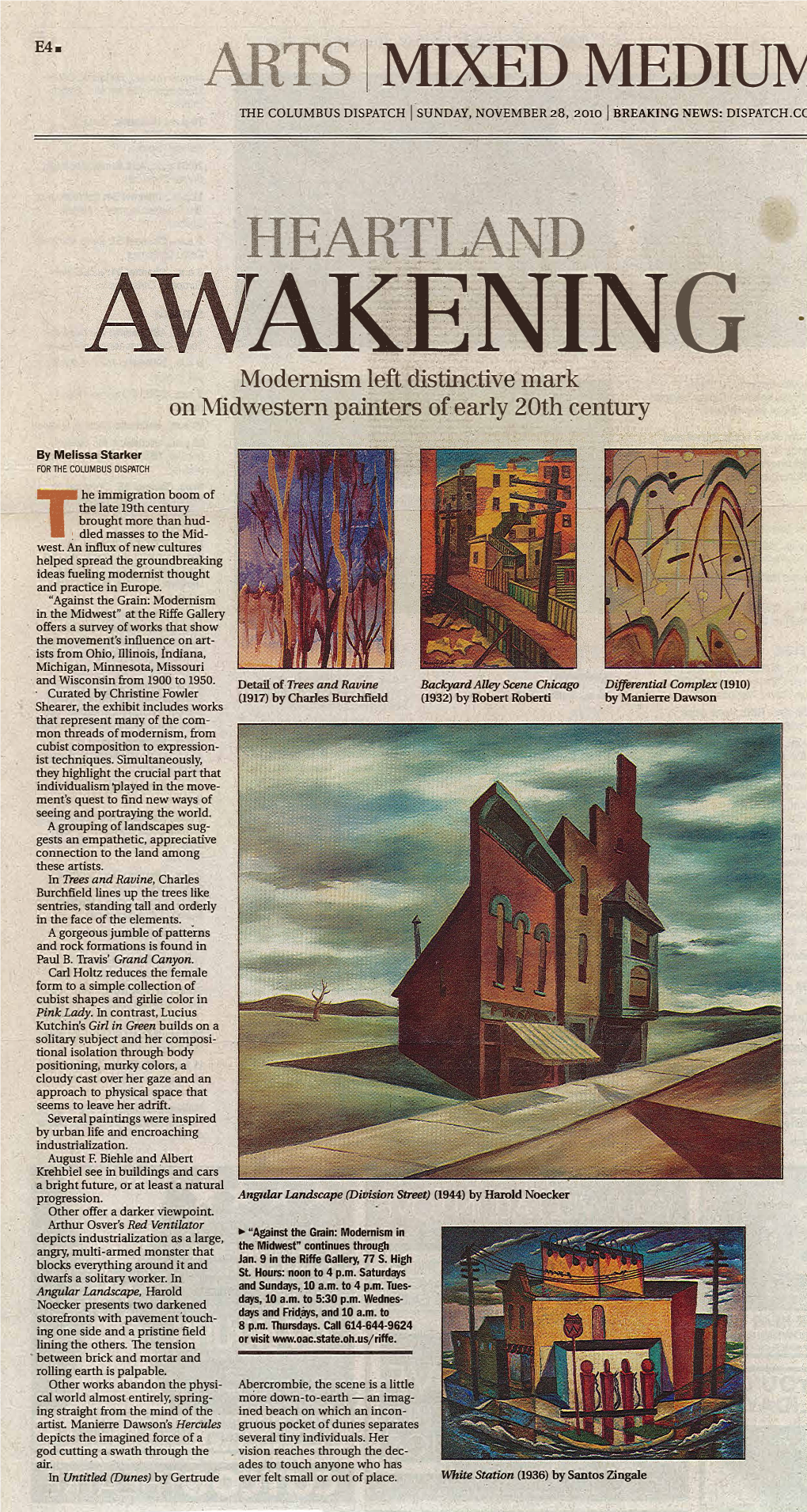

Gertrude Abercrombie

University Galleries’ Permanent Collection EDUCATOR RESOURCE Gertrude Abercrombie ABOUT THE ARTIST: Gertrude Abercrombie (b. 1909, Austin, Texas — d. 1977, Chicago) was a Chicago-based oil painter most known for her Surrealist/ Magical Realist portraits and landscapes. The life of the party and lover of jazz, Abercrombie was known in Chicago as the “queen of bohemian artists” (Seaman, 2017. Pg. 28). She was the daughter of traveling opera singers Lula Janes and Tom Abercrombie, who eventually settled in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois, where Abercrombie remained for most of her adult life. Abercrombie earned a bachelor’s degree in Romance Languages from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. She briefly studied figure drawing at the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as commercial art at the American Academy of Art in Chicago. After her death on July 3, 1977, much of Abercrombie’s work was donated to museums and other not-for-profit organizations per her last will and testament (Weininger & Smith, 1991. Pg. 34). Abercrombie's work is included in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Illinois State Museum, Springfield, Lewistown, Lockport; The Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Contem- porary Art, Chicago; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; and Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee (Karma, n.d.). ABOUT THE ARTWORK: Abercrombie’s paintings are open-ended and ambiguous, rendering familiar objects mysterious and bizarre. Regularly revisited motifs—a vast and desolate landscape, the full moon, a solitary woman, sparse interior spaces, cats, a single dead tree, doors leading to nowhere—weave an allegorical web of Abercrombie’s physiological and psychological experiences. -

A Finding Aid to the Gertrude Abercrombie Papers, Circa 1880-1986, Bulk 1935-1977, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Gertrude Abercrombie papers, circa 1880-1986, bulk 1935-1977, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines July 31, 2007 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1902-1976..................................................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, circa 1935-1977............................................................ 7 Series 3: Artist files, circa 1935-1977...................................................................... 8 Series 4: Writings and Notes, -

Julia Thecla: Undiscovered Worlds Joanna Gardner-Hugget

Via Sapientiae: Masthead Logo The nI stitutional Repository at DePaul University DePaul Art Museum Publications Academic Affairs 1-1-2006 Julia Thecla: Undiscovered Worlds Joanna Gardner-Hugget Louise Lincoln Recommended Citation Gardner-Hugget, Joanna and Lincoln, Louise, "Julia Thecla: Undiscovered Worlds" (2006). DePaul Art Museum Publications. 11. https://via.library.depaul.edu/museum-publications/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Affairs at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Art Museum Publications by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JULIA THECLA undiscovered worlds DEPAUL UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM JULIA THECLA undiscovered worlds DEPAUL UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM Julia Thecla Undiscovered Worlds September 14 - November 22, 2006 DePaul University Art Museum Chicago, Illinois Copyright © 2006 DePaul University ISBN-13: 978-0-9789074-1-9 ISBN-10: 0-9789074-1-8 Cover image: Julia Thecla. In the Clouds, 1960. Oil on canvas. DePaul University (cat. no. 26) Photo on page 5: Season’s Greetings, about 1945. Photomechanical reproduction. Courtesy of Barton Faist Studio and Gallery, Chicago Photo on page 42: Julia Thecla at an Art Institute of Chicago opening, about 1936. Courtesy of Barton Faist Studio and Gallery, Chicago ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We acknowledge with deep gratitude the generosity of individual lenders to the exhibition: Harlan Berk, River Forest, Illinois; John Corbett, Chicago; Leon and Marian Aschuler Despres, Chicago; Maximilienne Ewalt, San Francisco; Barton Faist, Chicago; Brenda Faist, Chicago; Daniel and Elizabeth McMullen, Naperville, Illinois; Edward Mogul, Chicago; and Montserrat Wassam, San Francisco, California. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 1 2 Annual Report 2005 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 www.mam.org 1 2 Annual Report 2005 Contents Board of Trustees . 4 Committees of the Board of Trustees . 4 President and Chairman’s Report . 6 Director’s Report . 9 Curatorial Report . 11 Exhibitions, Traveling Exhibitions . 14 Loans . 14 Acquisitions . 16 Publications . 35 Attendance . 36 Membership . 37 Education and Public Programs . 38 Year in Review . 39 Development . 43 Donors . 44 Support Groups . 51 Support Group Officers . 55 Staff . 58 Financial Report . 61 Financial Statements . 63 OPPOSITE: Ludwig Meidner, Self-Portrait (detail), 1912. See listing p. 16. PREVIOUS PAGE: Milwaukee Art Museum, Quadracci Pavilion designed by Santiago Calatrava as seen looking east down Wisconsin Avenue. www.mam.org 3 Board of Trustees As of August 30, 2005 BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEES OF Earlier European Arts Committee Jean Friedlander AND COMMITTEES THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jim Quirk Milton Gutglass George T. Jacobi MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair David Ritz Sheldon B. Lubar Sheldon B. Lubar Martha R. Bolles Helen Weber Chairman Chair Vice Chair and Secretary Barry Wind Andrew A. Ziegler Christopher S. Abele Barbara B. Buzard EDUCATION COMMITTEE President Donald W. Baumgartner Joanne Charlton Lori Bechthold Margaret S. Chester Christopher S. Abele Donald W. Baumgartner Frederic G. Friedman Stephen Einhorn Chair Vice President, Past President Terry A. Hueneke George A. Evans, Jr. Kim Abler Mary Ann LaBahn Eckhart Grohmann Frederic G. Friedman John Augenstein Marianne Lubar Frederick F. Hansen Assistant Secretary and James Barany P. M ichael Mahoney Avis M. Heller Legal Counsel José Chavez Betty Ewens Quadracci Arthur J. Laskin Terrence Coffman Mary Ann LaBahn James H. -

Gertrude Abercrombie Organized with Dan Nadel August 9–September 16, 2018 Opening Reception: Thursday, August 9, 2018, 6–8Pm

Gertrude Abercrombie Organized with Dan Nadel August 9–September 16, 2018 Opening reception: Thursday, August 9, 2018, 6–8pm Karma is pleased to present Gertrude Abercrombie’s first exhibition in New York since 1952. Abercrombie (1909–1977), a key figure in mid-century American Surrealism, was a sui generis artist who, from the late 1930s until her death, painted images populated by objects of personal significance — including moons, towers, cats, a barren tree, owls, hats, pennants, winding paths, grapes, bridges, Victorian furniture, shells, snails, and doors — to create allegories for her own often perilous emotional and psychological states. Often residing over these symbols was Gertrude herself, who appears in numerous pictures as proud observer, defiant actor, and witchy caricature. This exhibition, comprised of loans from institutions and private collections, is the most comprehensive look at Abercrombie’s artwork in nearly three decades. Abercrombie, the only daughter of Opera singer parents, grew up in Texas, Germany, and Aledo, Illinois, before settling in 1916 in Hyde Park, Chicago, where she spent the rest of her life. Aledo and its hills, ruins, and trees — the distinctly midwestern landscape she adored most — remained a constant in her work. She took art classes at the American Academy of Art and the School of the Art Institute. In 1933 she was appointed to the Public Works of Art Project (the first of the government supported arts programs), which gave her the time to find her subject matter and approach. Abercrombie exhibited in Art Institute Annuals and galleries in both Chicago and New York in the 1940s and 50s and became the center of several overlapping circles of Chicago and midwestern culture. -

Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture

ILLINOIS Liahy^BY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN AnoMiTEGTURE t/livMwir Of kill NOTICE: Return or renew all Library Materialsl The Minimum Fee for each Lost BooK is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN ^^ RPR^ ^ a:C 2 1998 L161—O-1096 LJj^«-*v Umermfi Paintm^ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS / 1^ m II IK WA.NUKRKKS Jovii- 1 iciin.m UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING College of Fine and Applied Arts Architecture Building Sunday, March 4, through Sunday, April 15, 1951 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS, URBANA IHtUSRARYOfTHt MAn G .j51 OHivERSirr OF laiNois COPYRIGHT 1951 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS MANUFACTURED IN 1 UK UNITED STATES ( )l AMIRKA (jV-/vtXv RICKER LIBRARY ARCHITECTURE is, L>- UNIVERSJT^ OF lUINfUS -t-^ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING GEORGE D. STODDARD President of the University DEAN REXFORD NEWCOMB Chairman, Festival of Contemporary Arts OPERATING COMMITTEE N. Britsky H. A. Schultz J. D. Hogan A. S. Weller J. W. Kennedy N. V. Ziroli E. C. Rae C. \'. Dono\an, Chairman STAFF COMMITTEE MEMBERS L. F, Bailey J. H. G. Lynch E. H. Betts M. B. Martin C. E. Bradbury R. Perlman E. J. Bransby A. J. Pulos C. W. Briggs J. W. Raushenberger L. R. -

1185 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board

1185 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board Meeting December 19, 2013 Trustees Room Louis Stokes Wing 12:00 Noon Present: Mr. Corrigan, Ms. Rodriguez, Mr. Seifullah, Mr. Parker, Mr. Hairston (arrived, 12:24 p.m.), Mr. Werner (arrived, 12:27 p.m.) Absent: Ms. Butts Mr. Corrigan called the meeting to order at 12:13 p.m. Approval of the Minutes MINUTES OF REGULAR BOARD Mr. Seifullah moved approval of the minutes for the MEETING OF 11/21/13 Regular Board Meeting; and the 11/19/13 Finance 11/21/13; FINANCE Committee Meeting. Mr. Parker seconded the motion, COMMITTEE which passed unanimously by roll call vote. MEETING OF 11/19/13 Presentation: Anne Marie Warren, Friends of the Approved Cleveland Public Library Before introducing Anne Marie Warren, Executive Director, Friends of the Cleveland Public Library, Mr. Corrigan stated that he recently attended the Friends Annual Meeting where he and Director Thomas became Ex- Offico board members. Ms. Warren congratulated the Library on the success of the passage of the levy and stated that the Friends was proud to be a partner in that major initiative. Ms. Warren acknowledged that in their 50 year history, the Friends provided $1,000,000 in financial support to the Library and look forward to continuing that support annually. Ms. Warren introduced the following new members of the Friends of the Cleveland Public Library: Aaron O’Brien, Baker & Hostetler LLP and John Siemborski, Ernst & Young. Mr. Corrigan thanked Ms. Warren for her presentation and expressed appreciation to the Friends for their partnership and support. -

The Great Depression the Great Depression of the Thirties Began in the United States with "Black Tuesday." on That Day, October 29, 1929, the Stock Market Crashed

WPA Prints - An Essay The WPA Prints constitute one of the many collections in the Kelvin Smith Library's Special Collections Research Center. This area of the library was specifically designed to provide a protective and controlled environment for rare books, manuscripts, and special collections, which, because of their rarity, value, fragility, ephemeral nature, or because they are part of a distinctive subject or author collection, require special care and handling. Among the Center's holdings, besides rare books, early imprints, and manuscripts, there are separate collections such as the E.J. Bohn papers and the Karal Ann Marling Collection, as well as reference books and bibliographies relating to them. Ernest J. Bohn was an important pioneer — locally, nationally, and internationally — in the field of public housing. In fact, he was directly responsible for the Ohio Public Housing Act, the very first in the nation. When Case art history professor Karal Marling donated her papers to the library, she wished that they join those of Mr. Bohn, who had assisted her research and allowed her free access to the WPA prints and to his entire collection. Mr. Bohn's papers contain records of his participation, as director of the Metropolitan Housing Authority, in the original federal New Deal art programs. On the library website are the Prints from the WPA, beautifully digitized and arranged alphabetically by artist. Additionally, there are two digital exhibits: African American Artists in the WPA Collection and Women Artists in the WPA Collection. Both of these focus on the work of particular artists and provide interesting biographical information on them. -

Cleveland Art School Exhibit Notes Copy

The Cleveland School Watercolor and Clay December 1, 2012 - March 10, 2013 The Cleveland School: Watercolor and Clay Exhibition Essay by William Robinson Northeast Ohio has produced a remarkable tradition of achievement in watercolor painting and ceramics. The artists who created this tradition are often identified as members of the Cleveland School, but that is only a convenient way of referring to a diverse array of painters and craftsmen who were active in a region that stretches out for hundreds of miles until it begins to collide with the cultural orbit of Toledo, Columbus, and Youngstown. The origins of this “school” are sometimes traced to the formation of the Cleveland Art Club in 1876, but artistic activity in the region predates that notable event. Notable artists were resident in Cleveland by at least the 1840s, supplying the growing shipping and industrial center with portraits, city views, and paintings to decorate domestic interiors. As the largest city in the region, Cleveland functioned like a magnet, drawing artists from surrounding communities to its art schools, museums, galleries, and thriving commercial art industries. Guy Cowan moved to Cleveland from East Liverpool, a noted center of pottery production, located on Ohio River, just across the Pennsylvania border. Charles Burchfield came from Salem and Viktor Schreckengost from Sebring, both for the purpose of studying at the Cleveland School of Art. To be sure, the flow of talent and ideas moved in multiple directions. Leading painters in Cleveland, such as Henry Keller and Auguste Biehle, established artists’ colonies in rural areas to west and south. William Sommer, although employed as a commercial lithographer in Cleveland, established a studio-home in the Brandywine Valley that drew other modernists to the country.