Metaphors in Jhumpa Lahiri's Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Parenting, Identity and Culture in an Era of Migration and Globalization: How Bangladeshi Parents Navigate and Negotiate Child-Rearing Practices in the Usa

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses October 2018 PARENTING, IDENTITY AND CULTURE IN AN ERA OF MIGRATION AND GLOBALIZATION: HOW BANGLADESHI PARENTS NAVIGATE AND NEGOTIATE CHILD-REARING PRACTICES IN THE USA Mohammad Mahboob Morshed University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the International and Comparative Education Commons Recommended Citation Morshed, Mohammad Mahboob, "PARENTING, IDENTITY AND CULTURE IN AN ERA OF MIGRATION AND GLOBALIZATION: HOW BANGLADESHI PARENTS NAVIGATE AND NEGOTIATE CHILD-REARING PRACTICES IN THE USA" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1373. https://doi.org/10.7275/12682074 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1373 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARENTING, IDENTITY AND CULTURE IN AN ERA OF MIGRATION AND GLOBALIZATION: HOW BANGLADESHI PARENTS NAVIGATE AND NEGOTIATE CHILD-REARING PRACTICES IN THE USA A Dissertation Presented by MOHAMMAD MAHBOOB MORSHED Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2018 College of Education © Copyright by Mohammad Mahboob Morshed 2018 All Rights Reserved PARENTING, IDENTITY AND CULTURE IN AN ERA OF MIGRATION AND GLOBALIZATION: HOW BANGLADESHI PARENTS NAVIGATE AND NEGOTIATE CHILD-REARING PRACTICES IN THE USA A Dissertation Presented by MOHAMMAD MAHBOOB MORSHED Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ Jacqueline R. -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

TIWARI-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf

Copyright by Bhavya Tiwari 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Bhavya Tiwari Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South Committee: Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Supervisor David Damrosch Martha Ann Selby Cesar Salgado Hannah Wojciehowski Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South by Bhavya Tiwari, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Dedication ~ For my mother ~ Acknowledgements Nothing is ever accomplished alone. This project would not have been possible without the organic support of my committee. I am specifically thankful to my supervisor, Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, for giving me the freedom to explore ideas at my own pace, and for reminding me to pause when my thoughts would become restless. A pause is as important as movement in the journey of a thought. I am thankful to Martha Ann Selby for suggesting me to subhead sections in the dissertation. What a world of difference subheadings make! I am grateful for all the conversations I had with Cesar Salgado in our classes on Transcolonial Joyce, Literary Theory, and beyond. I am also very thankful to Michael Johnson and Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski for patiently listening to me in Boston and Austin over luncheons and dinners respectively. I am forever indebted to David Damrosch for continuing to read all my drafts since February 2007. I am very glad that our paths crossed in Kali’s Kolkata. -

Voting Rights and Election Administration in America”

Testimony of John C. Yang President and Executive Director Asian Americans Advancing Justice – AAJC For Hearing on “Voting Rights and Election Administration in America” US House of Representatives Committee on House Administration Subcommittee on Elections October 17, 2019 Introduction The language barrier is one of the biggest impediments to the Asian American vote. Lagging behind non-Hispanic whites in voter participation, ensuring effective language assistance is paramount to closing that consistent gap. While the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) has been vital to ensuring language access and assistance to Asian Americans in national and local elections, and for increasing the community’s access to the ballot, more can be done to improve access to the ballot for limited English proficient Asian American voters. This testimony will detail the Asian American electorate and the language barriers facing Asian Americans as well as recommendations and best practices to providing language assistance. While Asian Americans are the nation’s fastest growing racial group and are quickly becoming a significant electoral force, the community will not be able to maximize its political power without access to the ballot. Organizational Information Asian Americans Advancing Justice – AAJC (Advancing Justice – AAJC) is a member of Asian Americans Advancing Justice (Advancing Justice), a national affiliation of five civil rights nonprofit organizations that joined together in 2013 to promote a fair and equitable society for all by working for civil and human rights and empowering Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and other underserved communities. The Advancing Justice affiliation is comprised of our nation’s oldest Asian American legal advocacy center located in San Francisco (Advancing Justice – ALC), our nation’s largest Asian American advocacy service organization located in Los Angeles (Advancing Justice – LA), the largest national Asian American policy advocacy organization located in Washington D.C. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Celebrates Rabindranath Tagore in Song Music & Dance

International Centre Goa and Information and Resource Center, Singapore Celebrates Rabindranath Tagore in Song Music & Dance Building a Better Asia In honour of the Visiting Delegates from various Asian countries 7.15 pm AT THE INTERNATIONAL CENTER GOA Dona Paula The Nippon Group of Foundations PROGRAMME 7:15 pm Inauguration of the Musical Evening with felicitation of artists at the hands of Smt. Vijayadevi Rane , Chairperson, Bal Bhavan 7:25 pm Welcome song by young artists from Goa 7: 30 pm Tagore songs by Smt. Swastika Mukhopadhyay Sangeet Bhavan, Viswa Bharati Univeristy, Shantiniketan 8:00 pm Recitation of Tagore’s Poem in English 8:05 pm Theme Dance – Ritu Ranga by Shri. Arup Mitra, Smt. Sujata Mitra, Smt. Anusuya Das & Shri. Saikat Mukherjee Viswa Bharati Univeristy, Shantiniketan Music Director: Swastika Mukhopadhyay Choreographer: Arup Mitra 8:50 pm Recitation of Tagore’s Poem in English 9:00 pm Sitar Recital & Fusion Music by Shri Manab Das , Goa College of Music, Goa Accompanied by Shri Vishu Shirodkar, Shri Mayuresh Vast, Shri Prakash Amonkar & Shri Prakash Khutwalkar 9:30 pm End of the programme The programme is presented by the Information & Resource Center and the International Centre Goa with the cooperation of PRATIDHWANI – A Bengali cultural group of artists from Bengal and Goa. BABA 2008 Goa “BUILDING A BETTER ASIA: FUTURE LEADERS’ DIALOGUE” 2007-08 Theme “BUILDING THE COMMON GOOD IN ASIA” 16-24 February, 2008 (Goa, India) www.buildingabetterasia.com The ultimate objective of the Building a Better Asia: Future Leaders’ Dialogue is to nurture future leaders for Asia so that they can contribute to the building of a better Asia in the future. -

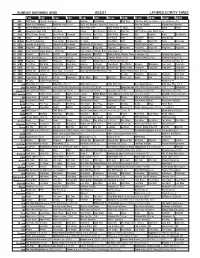

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by -

Studies in the History of Prostitution in North Bengal : Colonial and Post - Colonial Perspective

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST - COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TAMALI MUSTAFI Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR ANITA BAGCHI DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHUNPUR DARJEELING, PIN - 734013 WEST BENGAL SEPTEMBER, 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled ‘STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST - COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE’ has been prepared by me under the guidance of Professor Anita Bagchi, Department of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Date: 19.09.2016 Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohunpur Darjeeling, Pin - 734013 West Bengal CERTIFICATE I certify that Tamali Mustafi has prepared the thesis entitled ‘STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF PROSTITUTION IN NORTH BENGAL : COLONIAL AND POST – COLONIAL PERSPECTIVE’, of the award of Ph.D. degree of the University of North Bengal, under my guidance. She has carried out the work at the Department of History, University of North Bengal. Date: 19.09.2016 Department of History University of North Bengal Raja Rammohunpur Darjeeling, Pin - 734013 West Bengal ABSTRACT Prostitution is the most primitive practice in every society and nobody can deny this established truth. Recently women history is being given importance. Writing the history of prostitution in Bengal had already been started. But the trend of those writings does not make any interest to cover the northern part of Bengal which is popularly called Uttarbanga i.e. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism.