Writing Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin Spelling and Pronunciation 1 Latin Spelling and Pronunciation

Latin spelling and pronunciation 1 Latin spelling and pronunciation Latin spelling or orthography refers to the spelling of Latin words written in the scripts of all historical phases of Latin, from Old Latin to the present. All scripts use the same alphabet, but conventional spellings may vary from phase to phase. The Roman alphabet, or Latin alphabet, was adapted from the Old Italic alphabet to represent the phonemes of the Latin language. The Old Italic alphabet had in turn been borrowed from the Greek alphabet, itself adapted from the Phoenician alphabet. Latin pronunciation continually evolved over the centuries, making it difficult for speakers in one era to know how Latin was spoken in prior eras. A given phoneme may be represented by different letters in different periods. This article deals primarily with modern scholarship's best reconstruction of Classical Latin's phonemes (phonology) and the pronunciation and spelling used by educated people in the late Ancient Roman inscription in Roman square capitals. The words are separated by Republic, and then touches upon later engraved dots, a common but by no means universal practice, and long vowels are changes and other variants. marked by apices. Letters and phonemes In Latin spelling, individual letters mostly corresponded to individual phonemes, with three main exceptions: 1. Each vowel letter—⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨y⟩—represented both long and short vocalic phonemes. As for instance mons /ˈmoːns/ has long /oː/, pontem /ˈpontem/ short /o/. The long vowels were distinguished by apices in many Classical texts (móns), but are not always reproduced in modern copy. -

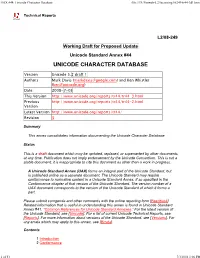

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Europe-II 8 Ancient and Other Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 12.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2019 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 12.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-22-1 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode12.0.0/) 1. -

Issues in the Representation of Pointed Hebrew in Unicode Third Draft, Peter Kirk, August 2003

Issues in the Representation of Pointed Hebrew in Unicode Third draft, Peter Kirk, August 2003 1. Introduction The Hebrew block of the Unicode Standard (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0590.pdf) is intended to include all of the characters needed for proper representation of Hebrew texts from all periods of the Hebrew language, including fully pointed and cantillated ancient texts such as that of the Hebrew Bible. It is also intended to cover other languages written in Hebrew script, including Aramaic as used in biblical and other religious texts1 as well as Yiddish and a few other modern languages. In practice there are a number of issues and minor deficiencies in the Hebrew block as currently defined, in version 4.0 of the Unicode Standard (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode4.0.0/), which affect its usefulness for representation of pointed Hebrew texts and of Hebrew script texts in some other languages. Some of these simply require clarification and agreed guidelines for implementers. Others require further discussion and decision, and possibly additions to the Unicode standard or other action by the Unicode Technical Committee. The conclusion reached in this paper is that two new Unicode characters should be proposed; other issues can be resolved by use of suitable sequences of existing characters, provided that such use is generally agreed by content providers and rendering systems. Several of these issues relate to different typographical conventions for publishing of Hebrew texts. It seems that a particular set of conventions is used for general publications in Hebrew, especially in Israel, but various other conventions, in which more fine distinctions are made, are used mainly for quality editions of biblical and other religious texts. -

The Twenty-Nine Enclitics of Meskwaki

The Twenty-Nine Enclitics of Meskwaki IVES GODDARD Smithsonian Institution INTRODUCTION Enclitics in Algonquian languages have received some attention (e.g., Bloom¿eld 1957:7, 131–132; Bloom¿eld 1962:459–462; Jolley 1984; Valentine 2001:72–73, 150–152; Goddard 2008:262–270; Quinn 2010; LeSourd 2011), but they are often classed with other particles and not explicitly labeled (Szabó 1981).1 Meskwaki enclitics will be of interest because they are clearly identi¿able as a formal class, and because it appears likely that Meskwaki has by far the largest repertoire of any language in the family. The present paper is perforce only a preliminary survey of the Meskwaki enclitics and their many interesting features. After the summary introduction there is a complete inventory followed by sections on idiomatic enclitic combinations, other idioms that include enclitics, multiple enclitics, and cognates and etymologies.2 The Meskwaki enclitics are particles (uninÀected words) of no more than three syllables that always attach to a preceding word (the host); in phonemic transcription they are separated from the host by a double hyphen (or equals sign: =) and this is also used to mark an enclitic when it is cited as a word. The questions of de¿nition and identi¿cation that dominate the recent general literature on enclitics thankfully do not arise. Meskwaki enclitics are 1. Of course, the terms enclitic and clitic have also sometimes been applied to af¿xes that are not enclitics, as in Szabó (1981). 2. The entries for the enclitics and other topical entries are numbered in parentheses and cross-referred to by non-italic numbers in parentheses (even within parentheses). -

IDEOGRAMS and SUPPLEMENTALS and REGIONAL INTERACTION AMONG AEGEAN and CYPRIOTE SCRIPTS* in This Paper I Wish to Discuss Several

IDEOGRAMS AND SUPPLEMENTALS AND REGIONAL INTERACTION AMONG AEGEAN AND CYPRIOTE SCRIPTS * In this paper I wish to discuss several major mysteries which still surround the development and spread of scripts in the middle A preliminary version of this article was delivered as a paper at the 6th International Colloquium on Aegean Prehistory which met in Athens August 30-Sepcember 5, 1987. I thank Jean-Pierre Olivier, lngo Pini and Edith Porada for reading the penultimate ve rsion and for making suggestions and corrections, parricularly in regard to the sign repertories of Linear A and B and the discussion of seals and sealings in notes 4 and 6, which have improved this final version. I am solely responsible for any shortcomings which remain. Ellen Davis kindly arranged for me to receive clear copies of photos of objects in the Cesnola Collection of the Metropolitam Museum of Art in New York. Nicolle Hirschfeld supplied a new, more accurate drawing of Enkomi 16.63, as part of her current work on Cypro-Minoan pottery marks. She also confirmed that Enkomi 4025 is a true osrrakon insc ription. We both thank Ors. Vassos Karageorghis and !no Nicolaou for permitting and facilitating this work. I use the following references and abbreviations: 2 Cesnola Atlas III : L. Palma di Cesnola, A Descriptive Atlas of the Cesnola Collection of Cypn·ote Antiquities in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2 III , New York 1894 ; CM = Cypro-Minoan; CS = Cypriote Syllabic Script ; Cyprominoica: E. Masson, Cyprominoica, SIMA 31:2, Goteborg 1974 ; Cyprus-Crete. Acts of the International Archaeological Symposium «The Relations between Cyprus and Crete, ca. -

A New Paradigm for Punctuation Albert Edward Krahn University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2014 A New Paradigm for Punctuation Albert Edward Krahn University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Linguistics Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Krahn, Albert Edward, "A New Paradigm for Punctuation" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 465. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/465 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW PARADIGM FOR PUNCTUATION by Albert E. Krahn A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2014 ABSTRACT A NEW PARADIGM FOR PUNCTUATION by Albert E. Krahn The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Fred R. Eckman This is a comprehensive study of punctuation, particularly the uses to which it has been put as writing developed over the centuries and as it gradually evolved from an aid to oral delivery to its use in texts that were read silently. The sudden need for standardization of punctuation which occurred with the start of printing spawned some small amount of interest in determining its purpose, but most works after printing began were devoted mainly to helping people use punctuation rather than try to discover why it was being used. Gradually, two main views on its purpose developed: it was being used for rhetorical purposes or it was needed to reveal the grammar in writing. -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N4178r L2/12-002

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4178R L2/12-002 2012-01-26 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for additions and corrections to Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform Source: UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project) Authors: Michael Everson and Steve Tinney Status: Liaison Contribution Date: 2012-01-26 The encoding of Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform in Unicode is a multi-phase process. In the first phase, the principal focus was signs from 2100 BCE onwards, with earlier material covered to the extent that it was clearly understood. This document adds signs that were inadvertently omitted from Phase 1, usually because they were not listed in the standard published sign lists. An exhaustive online sign-list is being prepared at http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/ogsl/, and the characters listed here are included in that list. 1. Signs omitted from the initial Cuneiform repertoire. CUNEIFORM SIGN KAP ELAMITE CUNEIFORM SIGN GA2 TIMES ASH2 CUNEIFORM SIGN KA TIMES ANSHE CUNEIFORM SIGN KA TIMES GUD CUNEIFORM SIGN KA TIMES SHUL CUNEIFORM SIGN LU2 SHESHIG TIMES BAD CUNEIFORM SIGN NU11 ROTATED NINETY DEGREES CUNEIFORM SIGN U U CUNEIFORM SIGN UR2 INVERTED CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN ONE QUARTER GUR CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN ONE HALF GUR CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN ELAMITE ONE THIRD CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN ELAMITE TWO THIRDS CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN ELAMITE FORTY CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN ELAMITE FIFTY CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN ELAMITE SIXTY CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN FOUR U VARIANT FORM CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN FIVE U VARIANT FORM CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN SIX U VARIANT FORM CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN SEVEN U VARIANT FORM CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN EIGHT U VARIANT FORM CUNEIFORM NUMERIC SIGN NINE U VARIANT FORM CUNEIFORM PUNCTUATION SIGN DIAGONAL QUADCOLON Page 1 2. -

Word Division in Bilingual Texts

Word division in bilingual texts Book or Report Section Published Version Dickey, E. (2017) Word division in bilingual texts. In: Nocchi Macedo, G. and Scappaticcio, M. C. (eds.) Signes dans les textes, textes sur les signes. Papyrologica Leodiensia (6). Presses universitaires de Liège, Liège, Belgium, pp. 159-175. ISBN 9782875621191 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/68827/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Presses universitaires de Liège All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Collection Papyrologica Leodiensia 6 Signes dans les textes, textes sur les signes Érudition, lecture et écriture dans le monde gréco-romain Actes du colloque international (Liège, 6–7 septembre 2013) Textes rassemblés et édités par Gabriel NOCCHI MACEDO et Maria Chiara SCAPPATICCIO Presses Universitaires de Liège 2017 Word Division in Bilingual Texts Eleanor DICKEY University of Reading Word division is normally considered to be one of the clear advantages that our civilization has over those of the ancients1. Because words are now divided at the time of writing, reading is for us a faster, easier, and more accurate process than it was in antiquity; indeed our heavily writing-dependent culture, which requires a nearly universal literacy rate, would arguably be impossible without word division. -

The Writing Revolution

9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iii The Writing Revolution Cuneiform to the Internet Amalia E. Gnanadesikan A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Amalia E. Gnanadesikan Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Amalia E. Gnanadesikan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

Document Title: AK-2688 Manuscript Title: <Ki Ya Mo We Wa . E Ne Se Ko Tti

Document title: AK-2688 Manuscript title: <ki ya mo we wa . e ne se ko tti . wi sa ke a ni .> (“When the cannibal giant was killed by Wisahkeha”) Manuscript date: 1911-1938 Manuscript location: National Anthropological Archives, Truman Michelson ms. #2688 Written by: Alfred Kiyana Written for: Truman Michelson Transcribed by: Ives Goddard Edited by: Ives Goddard Translated by: Ives Goddard Help with translation provided to Ives Goddard by: Adeline Wanatee (1990, 1991), Everett Kapayou (2001) Abbreviations: AK, K = Alfred Kiyana. TM = Truman Michelson. IG = Ives Goddard. AW = Adeline Wanatee. The original manuscript of this text is in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Anthropological Archives in the Museum Support Center, Suitland, Maryland (http://www.nmnh.si.edu/naa/). It consists of 51 pages of Meskwaki syllabary (“papepipo”). It was written by AK sometime between the years of 1911 and 1918. There is no contemporary translation. A version of IG’s translation was published in Brian Swann, ed., Voices from Four Directions: Contemporary Translations of the Native Literatures of North America, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 2004; this includes a discussion of some aspects of the story. This story is a winter story. Anyone observing traditional Meskwaki customs should be careful to read it aloud only when snow is on the ground. In the edition, Meskwaki is written in a phonemic transcription (one that writes all the distinct sounds consistently). There are eight phonemic vowels: i, i·, e, e·, a, a·, o, o·. There are eleven phonemic consonants: p, t, č, k, s, š, h, m, n, w, y.