The Twenty-Nine Enclitics of Meskwaki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin Spelling and Pronunciation 1 Latin Spelling and Pronunciation

Latin spelling and pronunciation 1 Latin spelling and pronunciation Latin spelling or orthography refers to the spelling of Latin words written in the scripts of all historical phases of Latin, from Old Latin to the present. All scripts use the same alphabet, but conventional spellings may vary from phase to phase. The Roman alphabet, or Latin alphabet, was adapted from the Old Italic alphabet to represent the phonemes of the Latin language. The Old Italic alphabet had in turn been borrowed from the Greek alphabet, itself adapted from the Phoenician alphabet. Latin pronunciation continually evolved over the centuries, making it difficult for speakers in one era to know how Latin was spoken in prior eras. A given phoneme may be represented by different letters in different periods. This article deals primarily with modern scholarship's best reconstruction of Classical Latin's phonemes (phonology) and the pronunciation and spelling used by educated people in the late Ancient Roman inscription in Roman square capitals. The words are separated by Republic, and then touches upon later engraved dots, a common but by no means universal practice, and long vowels are changes and other variants. marked by apices. Letters and phonemes In Latin spelling, individual letters mostly corresponded to individual phonemes, with three main exceptions: 1. Each vowel letter—⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨y⟩—represented both long and short vocalic phonemes. As for instance mons /ˈmoːns/ has long /oː/, pontem /ˈpontem/ short /o/. The long vowels were distinguished by apices in many Classical texts (móns), but are not always reproduced in modern copy. -

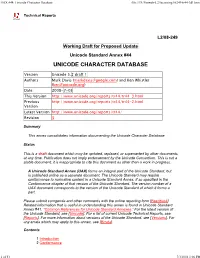

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

American-Indian-Place-Names-In

Classroom Activity—American Indians of Wisconsin Indian Place Names in Waukesha County Objective: Students will learn the prevalence of American Indian place names in Waukesha County and the meanings they carry. Students will use mapping skills in their identification of these places. Materials: • American Indian Place Names in Waukesha County sheet • Map of Waukesha County ONLINE UW-Libraries • Writing utensil Backstory: Many American Indian place names can be found in Waukesha County. Many of the communities and places within Waukesha County were established along or over the ancient trails and former villages of American Indian tribes. These place names throughout the county reflect this American Indian past. Activity • Pass out the American Indian Place Names in Waukesha County & Map of Waukesha County sheets and review the materials together. Have them guess if their town is derived from an American Indian name. • Have the students work on the Map of Waukesha County worksheet individually or in groups. • Discuss the answers together American Indian Place Names – Waukesha County TEACHER GUIDE Native Name Place Name & Meaning Location Potawatomi word meaning “fox.” Wauk-tsha was the Wauk-tsha name of the leader of the village, called Tchee-gas-cou-tak meaning “burnt” or “fire land.” Derived from the Ojibwe word meaning “Wild Rice Menomonee People”. Origins in the Potawatomi work maw-kwa and the Mawkwa or Ojibwe word makwanagoing. Both words mean “bear” Makwanagoing or “place of bears.” Derived from the Potawatomi word for the area, -

Cd109 IL16.Pdf

Livingston Fort MUKWONAGO Big NORTH Atkinson COLD SPRING Palmyra Bend LANCASTER LIBERTY CLIFTON IOWA Eagle JEFFERSON Mukwonago Muskego LINDEN Lake Koshkonong WAUKESHA PALMYRA VERNON Mineral Point MOSCOW EAGLE MIFFLIN KOSHKONONG Eagle Spring Lake Lancaster WALDWICK Brooklyn Rewey Edgerton Whitewater Lake Beulah MINERAL POINT Tichigan Lake Wind NEW GLARUS Potter Wind Lake Lake Lake ELLENBORO LIMA 109th Congress of the United States Waterford YORK New Glarus EXETER BROOKLYN LA GRANGE North SOUTH MILTON LANCASTER Blanchardville UNION PORTER LIMA TROY FULTON NORWAY BLANCHARD WHITEWATER East Evansville Troy WATERFORD Milton BELMONT Green Lake EAST TROY FAYETTE Water- WILLOW SPRINGS Whitewater Lake ford KENDALL Monticello North Lake LAFAYETTE ROCHESTER Platteville Belmont POTOSI HARRISON Rochester RICHMOND RACINE DOVER GRANT JOHNSTOWN SUGAR CREEK SPRING PRAIRIE LAMONT Tennyson Eagle PLATTEVILLE MOUNT Albany WALWORTH Browns Lake Argyle CENTER Lake ELK GROVE ARGYLE ADAMS WASHINGTON PLEASANT ALBANY JANESVILLE HARMONY Potosi Darlington MAGNOLIA Footville Elkhorn Burlington PARIS SEYMOUR DELAVAN W DARLINGTON Janesville GENEVA I SMELSER MONROE SPRING VALLEY S WIOTA JORDAN SYLVESTER DECATUR BURLINGTON C PLYMOUTH DARIEN Delavan LYONS BRIGHTON IOWA O LA PRAIRIE Dickeyville Brodhead Orfordville ROCK BRADFORD Delavan N Lake F Delavan Como o S Cuba Bohners Lake x Darien Lake R I City i Monroe v e N BENTON r LAFAYETTE Lake Como SHULLSBURG Browntown WHEATLAND Gratiot Benton Shullsburg Williams PERU JAMESTOWN Bay Lake GREEN Geneva Lake GRATIOT South Wayne -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Europe-II 8 Ancient and Other Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 12.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2019 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 12.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-22-1 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode12.0.0/) 1. -

Issues in the Representation of Pointed Hebrew in Unicode Third Draft, Peter Kirk, August 2003

Issues in the Representation of Pointed Hebrew in Unicode Third draft, Peter Kirk, August 2003 1. Introduction The Hebrew block of the Unicode Standard (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0590.pdf) is intended to include all of the characters needed for proper representation of Hebrew texts from all periods of the Hebrew language, including fully pointed and cantillated ancient texts such as that of the Hebrew Bible. It is also intended to cover other languages written in Hebrew script, including Aramaic as used in biblical and other religious texts1 as well as Yiddish and a few other modern languages. In practice there are a number of issues and minor deficiencies in the Hebrew block as currently defined, in version 4.0 of the Unicode Standard (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode4.0.0/), which affect its usefulness for representation of pointed Hebrew texts and of Hebrew script texts in some other languages. Some of these simply require clarification and agreed guidelines for implementers. Others require further discussion and decision, and possibly additions to the Unicode standard or other action by the Unicode Technical Committee. The conclusion reached in this paper is that two new Unicode characters should be proposed; other issues can be resolved by use of suitable sequences of existing characters, provided that such use is generally agreed by content providers and rendering systems. Several of these issues relate to different typographical conventions for publishing of Hebrew texts. It seems that a particular set of conventions is used for general publications in Hebrew, especially in Israel, but various other conventions, in which more fine distinctions are made, are used mainly for quality editions of biblical and other religious texts. -

Woodland Ways Folk Arts Apprenticeships Among Wisconsin Indians 1983–1993

WOODLAND WAYS FOLK ARTS APPRENTICESHIPS AMONG WISCONSIN INDIANS 1983–1993 Janet C. Gilmore & Richard March this manuscript is being mounted online in accordance with the fair use provisions of United States Copyright Act of 1976 (Title 17 of the United States Code). Section 107 of the Copyright Act expressly permits the fair use of copyrighted materials for teaching, scholarship, and research. DEDICATION To all of the Woodland Indian people whose masterful skills and insightful vision created the beautiful expressive works discussed herein. Thank you for your willingness to share your work and its meaning, your fervor to perpetuate the traditions, and your patience to acquaint me, an ignorant outsider, with your perspectives and ways. The Woodland ways embody an approach to art from which all artists can benefit and a spirit everyone needs to understand. — Rick March CONTENTS FOLK ARTS APPRENTICESHIPS Introduction 3 The Focus on Traditional Wisconsin Indian Arts 5 Outreach among the Indian Peoples 11 WISCONSIN’S WOODLAND INDIAN ARTISTS Wisconsin’s Indians 15 Ho-Chunks 19 Menominees 23 Ojibwas 27 Potawatomis 31 Oneidas 33 Stockbridge-Munsees 37 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 39 FOLK ARTS APPRENTICESHIPS INTRODUCTION n 1983, when I assumed the new position of the cultural groups involved. Cultural conservation Wisconsin’s Traditional and Ethnic Arts Coordinator, goes beyond the standard documentary techniques II learned of a pilot project sponsored by the Folk of interviewing tradition bearers, recording their Arts division of the National Endowment for the Arts expressions, and contributing the resulting reports, to create ten state-based apprenticeship programs. photographs, audiotapes, and sometimes traditionally- The apprenticeship idea fit my mission: to enhance made objects to archives and museums for study and appreciation for Wisconsin’s traditional and ethnic arts preservation. -

NEU Master Spreadsheet.Xlsx

Final NEU List Deadline of 9/30 has now passed State of Illinois Non‐Entitlement Units (NEUs) Receiving Payments from ARPA's Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery (“CLFR”) Fund NEU Recipient Population For Total First Tranche Second Tranche Non‐Entitlement Unit (NEU) County Number Allocation Allocation Allocation Allocation Claim Status Abingdon city IL2721 Knox 3,051 $414,765.78 $207,382.89 $207,382.89 Allocation claimed, portal complete Addieville village IL7414 Washington 238 $32,354.72 $16,177.36 $16,177.36 Allocation claimed, portal complete Addison village IL3876 Dupage 36,482 $4,959,516.65 $2,479,758.32 $2,479,758.33 Allocation claimed, portal complete Adeline village IL4885 Ogle 80 $10,875.54 $5,437.77 $5,437.77 Community non‐responsive, funds will be reallocated Albany village IL3258 Whiteside 863 $117,319.85 $58,659.93 $58,659.92 Allocation claimed, portal complete Albers village IL1924 Clinton 1,135 $154,296.68 $77,148.34 $77,148.34 Allocation claimed, portal complete Albion city IL8746 Edwards 1,899 $258,158.05 $129,079.03 $129,079.02 Allocation claimed, portal complete Aledo city IL7753 Mercer 3,432 $466,560.53 $233,280.26 $233,280.27 Allocation claimed, portal complete Alexis village IL2404 Warren 777 $105,628.65 $52,814.33 $52,814.32 Allocation claimed, portal complete Algonquin village IL4471 McHenry 30,897 $4,200,268.24 $2,100,134.12 $2,100,134.12 Allocation claimed, portal complete Alhambra village IL2750 Madison 650 $88,363.74 $44,181.87 $44,181.87 Allocation claimed, portal complete Allendale village IL3056 Wabash 477 $64,845.39 $32,422.69 $32,422.70 Allocation claimed, portal complete Allenville village IL5053 Moultrie 141 $19,168.13 $9,584.07 $9,584.06 Allocation claimed, portal complete Allerton village IL5230 Vermilion 266 $36,161.16 $18,080.58 $18,080.58 Allocation claimed, portal complete Alma village IL4214 Marion 303 $41,191.10 $20,595.55 $20,595.55 Allocation claimed, portal complete Alorton village see Cahokia Heights n/a St. -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers. -

IDEOGRAMS and SUPPLEMENTALS and REGIONAL INTERACTION AMONG AEGEAN and CYPRIOTE SCRIPTS* in This Paper I Wish to Discuss Several

IDEOGRAMS AND SUPPLEMENTALS AND REGIONAL INTERACTION AMONG AEGEAN AND CYPRIOTE SCRIPTS * In this paper I wish to discuss several major mysteries which still surround the development and spread of scripts in the middle A preliminary version of this article was delivered as a paper at the 6th International Colloquium on Aegean Prehistory which met in Athens August 30-Sepcember 5, 1987. I thank Jean-Pierre Olivier, lngo Pini and Edith Porada for reading the penultimate ve rsion and for making suggestions and corrections, parricularly in regard to the sign repertories of Linear A and B and the discussion of seals and sealings in notes 4 and 6, which have improved this final version. I am solely responsible for any shortcomings which remain. Ellen Davis kindly arranged for me to receive clear copies of photos of objects in the Cesnola Collection of the Metropolitam Museum of Art in New York. Nicolle Hirschfeld supplied a new, more accurate drawing of Enkomi 16.63, as part of her current work on Cypro-Minoan pottery marks. She also confirmed that Enkomi 4025 is a true osrrakon insc ription. We both thank Ors. Vassos Karageorghis and !no Nicolaou for permitting and facilitating this work. I use the following references and abbreviations: 2 Cesnola Atlas III : L. Palma di Cesnola, A Descriptive Atlas of the Cesnola Collection of Cypn·ote Antiquities in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2 III , New York 1894 ; CM = Cypro-Minoan; CS = Cypriote Syllabic Script ; Cyprominoica: E. Masson, Cyprominoica, SIMA 31:2, Goteborg 1974 ; Cyprus-Crete. Acts of the International Archaeological Symposium «The Relations between Cyprus and Crete, ca.