Cyclic Transit Probabilities of Long-Period Eccentric Planets Due to Periastron Precession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

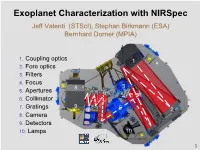

Exoplanet Characterization with Nirspec

Exoplanet Characterization with NIRSpec Jeff Valenti (STScI), Stephan Birkmann (ESA) Bernhard Dorner (MPIA) 1. Coupling optics 1 2. Fore optics 3. Filters 4. Focus 8 3 5. Apertures 6 4 6. Collimator 9 7. Gratings 7 5 2 8. Camera 9. Detectors 10. Lamps 10 1 NIRSpec Apertures Aperture Spectral Spatial S1600 1.6” 1.6” S400 0.4” 3.65” S200 0.2” 3.2” IFU 36 x 0.1” 3.6” MSA 2 x 95” 2 x 87” The S1600 aperture was designed for exoplanet observations 2 Noise Due to Jitter 1σ Jitter Jitter of 7 mas causes relative noise of 4 x 10-5 From PhD thesis Bernhard Dorner 3 NIRSpec Optical Configurations Grating Filter Wavelengths Resolution PRISM CLEAR 0.6 – 5.0 30 – 300 “100” F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 500 – 850 G140M F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “1000” G235M F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 700 – 1300 G395M F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 F070LP 0.7 – 1.2 1300 – 2300 G140H F100LP 1.0 – 1.8 “2700” G235H F170LP 1.7 – 3.0 1900 – 3600 G395H F290LP 2.9 – 5.0 4 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances 5 6 http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/jwst/nirspec-performances Example of High-Resolution Model Spectra G395H Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 7 Thermal Emission from a Hot Jupiter Adapted from Figure 4b of Burrows, Budaj, & Hubeny (2008) 8 Integrations and Exposures " An “exposure” is a sequence of integrations. " An “integration” is a sequence of groups, sampled up-the-ramp " One or more resets between integrations, but no other overheads " Currently using pixel-by-pixel resets, but row-by-row possible 9 Subarrays NX NY Frame time (s) Notes 2048 512 10.74 Full frame, 4 amps 2048 256 5.49 -

THE MASS of KOI-94D and a RELATION for PLANET RADIUS, MASS, and INCIDENT FLUX∗

The Astrophysical Journal, 768:14 (19pp), 2013 May 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/768/1/14 C 2013. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE MASS OF KOI-94d AND A RELATION FOR PLANET RADIUS, MASS, AND INCIDENT FLUX∗ Lauren M. Weiss1,12, Geoffrey W. Marcy1, Jason F. Rowe2, Andrew W. Howard3, Howard Isaacson1, Jonathan J. Fortney4, Neil Miller4, Brice-Olivier Demory5, Debra A. Fischer6, Elisabeth R. Adams7, Andrea K. Dupree7, Steve B. Howell2, Rea Kolbl1, John Asher Johnson8, Elliott P. Horch9, Mark E. Everett10, Daniel C. Fabrycky11, and Sara Seager5 1 B-20 Hearst Field Annex, Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] 2 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 3 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 4 Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, 275 Interdisciplinary Sciences Building (ISB), Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 5 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 6 Department of Astronomy, Yale University, P.O. Box 208101, New Haven, CT 06510-8101, USA 7 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 8 California Institute of Technology, 1216 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA 91106, USA 9 Southern Connecticut State University, Department of Physics, 501 Crescent St., New Haven, CT 06515, USA 10 National Optical Astronomy Observatory, 950 N. Cherry Ave, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA 11 The Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 S. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

A&A 562, A92 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201321493 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics Li depletion in solar analogues with exoplanets Extending the sample, E. Delgado Mena1,G.Israelian2,3, J. I. González Hernández2,3,S.G.Sousa1,2,4, A. Mortier1,4,N.C.Santos1,4, V. Zh. Adibekyan1, J. Fernandes5, R. Rebolo2,3,6,S.Udry7, and M. Mayor7 1 Centro de Astrofísica, Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] 2 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, C/ Via Lactea s/n, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 3 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 4 Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal 5 CGUC, Department of Mathematics and Astronomical Observatory, University of Coimbra, 3049 Coimbra, Portugal 6 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC, Spain 7 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland Received 18 March 2013 / Accepted 25 November 2013 ABSTRACT Aims. We want to study the effects of the formation of planets and planetary systems on the atmospheric Li abundance of planet host stars. Methods. In this work we present new determinations of lithium abundances for 326 main sequence stars with and without planets in the Teff range 5600–5900 K. The 277 stars come from the HARPS sample, the remaining targets were observed with a variety of high-resolution spectrographs. Results. We confirm significant differences in the Li distribution of solar twins (Teff = T ± 80 K, log g = log g ± 0.2and[Fe/H] = [Fe/H] ±0.2): the full sample of planet host stars (22) shows Li average values lower than “single” stars with no detected planets (60). -

Sunqm-1S2: Comparing to Other Star-Planet Systems, Our Solar System Has a Nearly Perfect {N,N} QM Structure 1

Yi Cao, SunQM-1s2: Comparing to other star-planet systems, our Solar system has a nearly perfect {N,n} QM structure 1 SunQM-1s2: Comparing to other star-planet systems, our Solar system has a nearly perfect {N,n//6} QM structure Yi Cao Ph.D. of biophysics, a citizen scientist of QM. E-mail: [email protected] © All rights reserved The major part of this work started from 2016. Abstract The Solar QM {N,n//6} structure has been successful not only for modeling the Solar system from Sun core to Oort cloud, but also in matching the size of white dwarf, neutron star and even black hole. In this paper, I have used this model to further scan down (and up) in our world. It is interesting to find that on the small end, the r(s) of hydrogen atom, proton and quark match {-12,1}, {-15,1} and {-17,1} respectively. On the large end, our Milky way galaxy, the Virgo super cluster have their r(s) match {8,1}, and {10,1} respectively. In a second estimation, some elementary particles like electron, up quark, down quark, … may have their {N,n} QM structures match {-17,1}, {-17,2}, {-17,3} … respectively. In a third estimation, the r(s) of super-massive black hole of Andromeda galaxy and Milky way galaxy match {2,1} and {1,1} respectively. However, so far the Solar QM {N,n} structure has not been re-produced in other exoplanetary systems (like TRAPPIST-1, HD 10180, Kepler-90, Kelper-11, 55-Cacri). -

![Arxiv:2105.11583V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 2 Jul 2021 Keck-HIRES, APF-Levy, and Lick-Hamilton Spectrographs](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2105-11583v2-astro-ph-ep-2-jul-2021-keck-hires-apf-levy-and-lick-hamilton-spectrographs-364203.webp)

Arxiv:2105.11583V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 2 Jul 2021 Keck-HIRES, APF-Levy, and Lick-Hamilton Spectrographs

Draft version July 6, 2021 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 The California Legacy Survey I. A Catalog of 178 Planets from Precision Radial Velocity Monitoring of 719 Nearby Stars over Three Decades Lee J. Rosenthal,1 Benjamin J. Fulton,1, 2 Lea A. Hirsch,3 Howard T. Isaacson,4 Andrew W. Howard,1 Cayla M. Dedrick,5, 6 Ilya A. Sherstyuk,1 Sarah C. Blunt,1, 7 Erik A. Petigura,8 Heather A. Knutson,9 Aida Behmard,9, 7 Ashley Chontos,10, 7 Justin R. Crepp,11 Ian J. M. Crossfield,12 Paul A. Dalba,13, 14 Debra A. Fischer,15 Gregory W. Henry,16 Stephen R. Kane,13 Molly Kosiarek,17, 7 Geoffrey W. Marcy,1, 7 Ryan A. Rubenzahl,1, 7 Lauren M. Weiss,10 and Jason T. Wright18, 19, 20 1Cahill Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 2IPAC-NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 4Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 5Cahill Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 6Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Pennsylvania State University, 525 Davey Lab, University Park, PA 16802, USA 7NSF Graduate Research Fellow 8Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 9Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 10Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai`i, -

A Super-Earth Transiting a Naked-Eye Star

A Super-Earth Transiting a Naked-Eye Star The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Winn, Joshua N. et al. “A SUPER-EARTH TRANSITING A NAKED-EYE STAR.” The Astrophysical Journal 737.1 (2011): L18. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2041-8205/737/1/l18 Publisher IOP Publishing Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/71127 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ ACCEPTED VERSION,JULY 6, 2011 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 11/10/09 A SUPER-EARTH TRANSITING A NAKED-EYE STAR⋆ JOSHUA N. WINN1, JAYMIE M. MATTHEWS2,REBEKAH I. DAWSON3 ,DANIEL FABRYCKY4,5 , MATTHEW J. HOLMAN3, THOMAS KALLINGER2,6,RAINER KUSCHNIG6,DIMITAR SASSELOV3,DIANA DRAGOMIR5,DAVID B. GUENTHER7, ANTHONY F. J. MOFFAT8 , JASON F. ROWE9 ,SLAVEK RUCINSKI10,WERNER W. WEISS6 ApJ Letters, in press ABSTRACT We have detected transits of the innermost planet “e” orbiting55Cnc(V =6.0), based on two weeks of nearly continuous photometric monitoring with the MOST space telescope. The transits occur with the period (0.74 d) and phase that had been predicted by Dawson & Fabrycky, and with the expected duration and depth for the +0.051 crossing of a Sun-like star by a hot super-Earth. Assuming the star’s mass and radius to be 0.963−0.029 M⊙ and 0.943 ± 0.010 R⊙, the planet’s mass, radius, and mean density are 8.63 ± 0.35 M⊕,2.00 ± 0.14 R⊕, and +1.5 −3 5.9−1.1 g cm . -

![Arxiv:1904.05358V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 10 Apr 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1935/arxiv-1904-05358v1-astro-ph-ep-10-apr-2019-481935.webp)

Arxiv:1904.05358V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 10 Apr 2019

Draft version April 12, 2019 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX62 The Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Survey: Giant Planet and Brown Dwarf Demographics From 10{100 AU Eric L. Nielsen,1 Robert J. De Rosa,1 Bruce Macintosh,1 Jason J. Wang,2, 3, ∗ Jean-Baptiste Ruffio,1 Eugene Chiang,3 Mark S. Marley,4 Didier Saumon,5 Dmitry Savransky,6 S. Mark Ammons,7 Vanessa P. Bailey,8 Travis Barman,9 Celia´ Blain,10 Joanna Bulger,11 Jeffrey Chilcote,1, 12 Tara Cotten,13 Ian Czekala,3, 1, y Rene Doyon,14 Gaspard Duchene^ ,3, 15 Thomas M. Esposito,3 Daniel Fabrycky,16 Michael P. Fitzgerald,17 Katherine B. Follette,18 Jonathan J. Fortney,19 Benjamin L. Gerard,20, 10 Stephen J. Goodsell,21 James R. Graham,3 Alexandra Z. Greenbaum,22 Pascale Hibon,23 Sasha Hinkley,24 Lea A. Hirsch,1 Justin Hom,25 Li-Wei Hung,26 Rebekah Ilene Dawson,27 Patrick Ingraham,28 Paul Kalas,3, 29 Quinn Konopacky,30 James E. Larkin,17 Eve J. Lee,31 Jonathan W. Lin,3 Jer´ ome^ Maire,30 Franck Marchis,29 Christian Marois,10, 20 Stanimir Metchev,32, 33 Maxwell A. Millar-Blanchaer,8, 34 Katie M. Morzinski,35 Rebecca Oppenheimer,36 David Palmer,7 Jennifer Patience,25 Marshall Perrin,37 Lisa Poyneer,7 Laurent Pueyo,37 Roman R. Rafikov,38 Abhijith Rajan,37 Julien Rameau,14 Fredrik T. Rantakyro¨,39 Bin Ren,40 Adam C. Schneider,25 Anand Sivaramakrishnan,37 Inseok Song,13 Remi Soummer,37 Melisa Tallis,1 Sandrine Thomas,28 Kimberly Ward-Duong,25 and Schuyler Wolff41 1Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 2Department of Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 4NASA Ames Research Center, Mountain View, CA 94035, USA 5Los Alamos National Laboratory, P.O. -

Exoplanet.Eu Catalog Page 1 # Name Mass Star Name

exoplanet.eu_catalog # name mass star_name star_distance star_mass OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L b 13.6 OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L 4500.0 0.048 11 Com b 19.4 11 Com 110.6 2.7 11 Oph b 21 11 Oph 145.0 0.0162 11 UMi b 10.5 11 UMi 119.5 1.8 14 And b 5.33 14 And 76.4 2.2 14 Her b 4.64 14 Her 18.1 0.9 16 Cyg B b 1.68 16 Cyg B 21.4 1.01 18 Del b 10.3 18 Del 73.1 2.3 1RXS 1609 b 14 1RXS1609 145.0 0.73 1SWASP J1407 b 20 1SWASP J1407 133.0 0.9 24 Sex b 1.99 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 24 Sex c 0.86 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 2M 0103-55 (AB) b 13 2M 0103-55 (AB) 47.2 0.4 2M 0122-24 b 20 2M 0122-24 36.0 0.4 2M 0219-39 b 13.9 2M 0219-39 39.4 0.11 2M 0441+23 b 7.5 2M 0441+23 140.0 0.02 2M 0746+20 b 30 2M 0746+20 12.2 0.12 2M 1207-39 24 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1207-39 b 4 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1938+46 b 1.9 2M 1938+46 0.6 2M 2140+16 b 20 2M 2140+16 25.0 0.08 2M 2206-20 b 30 2M 2206-20 26.7 0.13 2M 2236+4751 b 12.5 2M 2236+4751 63.0 0.6 2M J2126-81 b 13.3 TYC 9486-927-1 24.8 0.4 2MASS J11193254 AB 3.7 2MASS J11193254 AB 2MASS J1450-7841 A 40 2MASS J1450-7841 A 75.0 0.04 2MASS J1450-7841 B 40 2MASS J1450-7841 B 75.0 0.04 2MASS J2250+2325 b 30 2MASS J2250+2325 41.5 30 Ari B b 9.88 30 Ari B 39.4 1.22 38 Vir b 4.51 38 Vir 1.18 4 Uma b 7.1 4 Uma 78.5 1.234 42 Dra b 3.88 42 Dra 97.3 0.98 47 Uma b 2.53 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma c 0.54 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma d 1.64 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 51 Eri b 9.1 51 Eri 29.4 1.75 51 Peg b 0.47 51 Peg 14.7 1.11 55 Cnc b 0.84 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc c 0.1784 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc d 3.86 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc e 0.02547 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc f 0.1479 55 -

The Spitzer Search for the Transits of HARPS Low-Mass Planets II

A&A 601, A117 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201629270 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics The Spitzer search for the transits of HARPS low-mass planets II. Null results for 19 planets? M. Gillon1, B.-O. Demory2; 3, C. Lovis4, D. Deming5, D. Ehrenreich4, G. Lo Curto6, M. Mayor4, F. Pepe4, D. Queloz3; 4, S. Seager7, D. Ségransan4, and S. Udry4 1 Space sciences, Technologies and Astrophysics Research (STAR) Institute, Université de Liège, Allée du 6 Août 17, Bat. B5C, 4000 Liège, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] 2 University of Bern, Center for Space and Habitability, Sidlerstrasse 5, 3012 Bern, Switzerland 3 Cavendish Laboratory, J. J. Thomson Avenue, Cambridge CB3 0HE, UK 4 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 Chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 5 Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742-2421, USA 6 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85478 Garching bei München, Germany 7 Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Received 8 July 2016 / Accepted 15 December 2016 ABSTRACT Short-period super-Earths and Neptunes are now known to be very frequent around solar-type stars. Improving our understanding of these mysterious planets requires the detection of a significant sample of objects suitable for detailed characterization. Searching for the transits of the low-mass planets detected by Doppler surveys is a straightforward way to achieve this goal. Indeed, Doppler surveys target the most nearby main-sequence stars, they regularly detect close-in low-mass planets with significant transit probability, and their radial velocity data constrain strongly the ephemeris of possible transits. -

The HARPS Search for Southern Extra-Solar Planets

The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets. III. Three Saturn-mass planets around HD 93083, HD 101930 and HD 102117 C. Lovis, M. Mayor, François Bouchy, F. Pepe, D. Queloz, N. C. Santos, S. Udry, W. Benz, Jean-Loup Bertaux, C. Mordasini, et al. To cite this version: C. Lovis, M. Mayor, François Bouchy, F. Pepe, D. Queloz, et al.. The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets. III. Three Saturn-mass planets around HD 93083, HD 101930 and HD 102117. Astronomy and Astrophysics - A&A, EDP Sciences, 2005, 437 (3), pp.1121-1126. 10.1051/0004- 6361:20052864. hal-00017981 HAL Id: hal-00017981 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00017981 Submitted on 17 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A&A 437, 1121–1126 (2005) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20052864 & c ESO 2005 Astrophysics The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets III. Three Saturn-mass planets around HD 93083, HD 101930 and HD 102117 C. Lovis1, M. Mayor1, F. Bouchy2,F.Pepe1,D.Queloz1,N.C.Santos3,1, S. Udry1,W.Benz4, J.-L. Bertaux5, C.