Oil Prices and Stock Markets: a Review of the Theory and Empirical Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTRONIC, ELECTRICAL & SYSTEMS ENGINEERING Beng Final Year Project (EE3P) Ahmed Zaidi 1153609 Forecasting Weekly WTI Crude

ELECTRONIC, ELECTRICAL & SYSTEMS ENGINEERING BEng Final Year Project (EE3P) Ahmed Zaidi 1153609 Forecasting Weekly WTI Crude Oil using Twitter Sentiment of US Foreign Policy and Oil Companies Dr. Mourad Oussalah Abstract The drop in crude oil price during late 2014 has had a significant impact on all nations. While some countries have reaped the benefits of low oil prices, others have suffered greatly. As a result, it is no surprise that many academics have attempted to develop reliable models to forecast crude oil price. In the age of information and social media, the role of Twitter and Facebook has become increasingly more relevant in understanding our environment. Many academics have exploited this wealth of data to extract features including sentiment and word frequency to build reliable forecasting models for financial instruments such as stocks. These methodologies, however, remain unexplored for the prediction of crude oil prices. The purpose of this investigation to develop a novel model that uses sentiment of United States foreign policy and oil companies’ to forecast the direction of weekly WTI crude oil prices. The investigation is divided into three parts: 1) a methodology of collecting tweets relevant to US foreign policy and oil companies’; 2) a statistical analysis of the novel features using Granger Causality Test; 3) the development and evaluation of three machine learning classifiers including Naïve Bayes, ANNs, and SVM to predict the direction of weekly WTI crude oil. The findings of the statistical analysis showed strong correlation between the novel inputs and WTI crude oil price. The results of the statistical tests were then used in the development of the predictive model. -

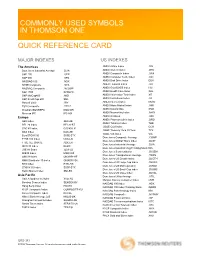

Thomson One Symbols

THOMSON ONE SYMBOLS QUICK REFERENCE CARD QUOTES FOR LISTED SECURITIES TO GET A QUOTE FOR TYPE EXAMPLE Specific Exchange Hyphen followed by exchange qualifier after the symbol IBM-N (N=NYSE) Warrant ' after the symbol IBM' When Issued 'RA after the symbol IBM'RA Class 'letter representing class IBM'A Preferred .letter representing class IBM.B Currency Rates symbol=-FX GBP=-FX QUOTES FOR ETF TO GET A QUOTE FOR TYPE Net Asset Value .NV after the ticker Indicative Value .IV after the ticker Estimated Cash Amount Per Creation Unit .EU after the ticker Shares Outstanding Value .SO after the ticker Total Cash Amount Per Creation Unit .TC after the ticker To get Net Asset Value for CEF, type XsymbolX. QRG-383 Date of issue: 15 December 2015 © 2015 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Thomson Reuters disclaims any and all liability arising from the use of this document and does not guarantee that any information contained herein is accurate or complete. This document contains information proprietary to Thomson Reuters and may not be reproduced, transmitted, or distributed in whole or part without the express written permission of Thomson Reuters. THOMSON ONE SYMBOLS Quick Reference Card MAJOR INDEXES US INDEXES THE AMERICAS INDEX SYMBOL Dow Jones Industrial Average .DJIA Airline Index XAL Dow Jones Composite .COMP AMEX Computer Tech. Index XCI MSCI ACWI 892400STRD-MS AMEX Institutional Index XII MSCI World 990100STRD-MS AMEX Internet Index IIX MSCI EAFE 990300STRD-MS AMEX Oil Index XOI MSCI Emerging Markets 891800STRD-MS AMEX Pharmaceutical Index -

Oil Prices and Stock Markets

WORKING PAPER SERIES Oil Prices and Stock Markets Stavros Degiannakis, George Filis, and Vipin Arora June 2017 This paper is released to encourage discussion and critical comment. The analysis and conclusions expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Independent Statistics & Analysis U.S. Energy Information Administration www.eia.gov Washington, DC 20585 June 2017 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 About the Authors ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 8 2. Theoretical Transmission Mechanisms Between Oil and Stock Market Returns ................................... 10 2.1 Stock valuation channel ................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Monetary channel ............................................................................................................................ 10 2.3. Output channel .............................................................................................................................. -

Copyrighted Material

P1: JYS ind JWBK304-Katsanos November 22, 2008 21:44 Printer: Yet to come Index abbreviations’ list 382–3 artificial neural networks 25, 154–5, ABS(DATA ARRAY) 379 168–71, 172, 215, 221–33, 357–65, ADM see Archer Daniels Midlands 371 ADRs 47, 86, 371 see also fuzzy logic; genetic algorithm advance-decline line 371 combined trading strategy 226–33, 360–3 ADX 140–3, 271–3, 276, 280–5 concepts 25, 154–5, 168–71, 172, 215, ADX(PERIODS) 379 221–33, 357–65, 371 AEX 82 conventional system comparisons 215, agricultural commodities 52–5 221–33 ALERT() 379 critique 169–71, 172, 221–33 Allianz 203 disparity 224–33, 359–60 aluminium 59–61, 249, 257, 259, 291 dynamic considerations 233 Amex Gold BUGS Index (HUI) FTSE system 215, 221–33, 357–65 concepts 63 hidden neurons 223, 225–33, 374 weighting method 63 hybrid strategy 172, 226–33, 363–5 Amex Oil Index (XOI) 30, 49–50, input considerations 221–2, 224–9, 233 55–8, 79–82, 216–33, 236–44, network architecture 230–2 357–65 nonlinear relationships 25 composition 56–7 optimization factors 168–71, 226–33 concepts 55–8, 216–33, 236–44 output considerations 226–9 correlations 57–8, 236–44 problems 222–3, 226, 232–3 S&P 500 79–82, 236–44 ROC 222–33, 357–60 weighting method 56–7 sensitivity analysis 226 ANOVA, concepts 161–2 testing procedures 223–9 Apache Corp. 56–7 total net profit 225–33 appendices 297–370COPYRIGHTEDtrading MATERIAL specifications 229–30 arbitrage 371 training 168–71, 172, 223–33 Archer Daniels Midlands (ADM) Asia Pacific Fund 251, 254–9 235 Asian crisis of 1997 78 Aristotle 111 Asian markets 7, 12–15, 74–5, 78 artificial intelligence asset allocations concepts 168–73 see also dynamic . -

Peak Oil News

Peak Oil News A Compilation of New Developments, Analysis, and Web Postings Tom Whipple, Editor Wednesday, December 03, 2008 Current Developments 1. OIL RISES SLIGHTLY AFTER PLUNGING TO 3-YEAR LOW Pablo Gorondi Associated Press Writer December 3, 2008 Oil prices rose slightly Wednesday but remained near three-year lows as investors tried to gauge how much the slowdown in U.S. and Chinese economies will hurt demand for crude. By midday in Europe, light, sweet crude for January delivery was up 30 cents to $47.26 a barrel in electronic trading on the New York Mercantile Exchange. The contract fell $2.32 overnight to settle at $46.96 after touching $46.82, the lowest level since May 20, 2005, when it traded at $46.20. In London, January Brent crude rose 30 cents to $45.74 on the ICE Futures exchange. "The rallies we've seen have been false rallies, relief rallies," said Mark Pervan, senior commodity strategist with ANZ Bank in Melbourne. "The mood is overwhelmingly bearish at the moment." 2. OIL RISES FROM 3-YEAR LOW AS OPEC SIGNALS PLAN TO CUT SUPPLIES By Christian Schmollinger and Grant Smith Dec. 3 (Bloomberg) -- Crude oil rebounded from a three-year low on speculation OPEC will cut production further this month to check the collapse in prices. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries intends to redice output when it meets on Dec. 17 in Algeria, Qatar’s Oil Minister Abdullah bin Hamad al- Attiyah said today. The U.S. Energy Department releases its weekly report on fuel inventories later today. -

Intermarket Trading Strategies

visit for more: http://trott.tv Your Source For Knowledge P1: JYS FM JWBK304-Katsanos November 22, 2008 14:21 Printer: Yet to come To my wife Erifili v P1: JYS FM JWBK304-Katsanos November 22, 2008 14:21 Printer: Yet to come Intermarket Trading Strategies i P1: JYS FM JWBK304-Katsanos November 22, 2008 14:21 Printer: Yet to come For other titles in the Wiley Trading Series please see www.wiley.com/finance ii P1: JYS FM JWBK304-Katsanos November 22, 2008 14:21 Printer: Yet to come INTERMARKET TRADING STRATEGIES Markos Katsanos A John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., Publication iii P1: JYS FM JWBK304-Katsanos November 22, 2008 14:21 Printer: Yet to come Copyright C 2008 Markos Katsanos Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London, ECIN 8TS, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620. -

Commonly Used Symbols Quick Reference Card

COMMONLY USED SYMBOLS IN THOMSON ONE QUICK REFERENCE CARD MAJOR INDEXES US INDEXES The Americas AMEX Airline Index .XAL Dow Jones Industrial Average .DJIA AMEX Biotech Index .BTK S&P 100 .OEX AMEX Composite Index .XAX S&P 500 .SPX AMEX Computer Tech. Index .XCI NASDAQ 100 .NDX AMEX Disk Drive Index DDX NYSE Composite .NYA AMEX Financial Index .XFI NASDAQ Composite .NCOMP AMEX Gold BUGS Index HUI S&P 1500 SPSUPX AMEX Health Care Index XHL S&P MidCap400 .MID AMEX Information Tech Index XIT S&P Small Cap 600 SML AMEX Institutional Index .XII Russell 2000 .RIY AMEX Internet Index IIX/IIV TSX Composite .TTT-T AMEX Major Market Index .XMI Brazilian IBOVESPA IBOV-BR AMEX Natural Gas XNG Mexican IPC IPC-MX AMEX Networking Index .NWX AMEX Oil Index .XOI Europe AMEX Pharmaceutical Index .DRG AEX Index AEX-AE AMEX Tobacco Index TOB BEL 20 Index BEL20-BT CBOE Gold Index GOX CAC 40 Index CAC40-FR CBOE Treasury Yield 30 Year TYX DAX Index DAX-XE CBOE VIX Index VIX EuroSTOXX 50 SX5E-STX Dow Jones Composite Average .COMP FTSE 100 Index UKX-LN Dow Jones Global Titans Index .DJGT FTSE ALL SHARE ASX-LN Dow Jones Industrial Average .DJIA IBEX 35 Index IB-MC Dow Jones Industrial Avg Tracking Stock DIA JSE All Share J203-JO Dow Jones Semiconductor .DJSEM MIB30 Index MIB30-MI Dow Jones Transportation Average .TRAN OMX Helsinki OMXHPI-HE Dow Jones US Growth Index .DJGTH OMX Stockholm 30 Index OMXS30-SK Dow Jones US Large Cap Index .DJLRG RTS Index RTSI-RS Dow Jones US Mid Cap Index .DJMID STOXX 50 Index SX5P-STX Dow Jones US Small Cap Index .DJSMC Swiss Market -

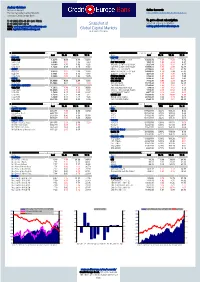

Economic Overview

Andrey Golubev Research Analyst Online Research: Russian & Global Capital Markets http://www.crediteurope.ru/en/research/ Treasury, Credit Europe Bank T: +7 (495) 725 40 40 (ext. 7239) To get a direct subscription, F: +7 (495) 725 40 13 Snapshot of Send an inquiry e-mail to: MAIL: [email protected] Global Capital Markets [email protected] BBG: [email protected] g 10.11.2007 [17:21 MSK] Gggg gg CURRENCIES MAJOR EQUITY INDICES Name Last 1D, % 1W, % 1Y, % Name Last 1D, % 1W, % 1Y, % MAJORS MAJORS EUR/USD 1.4679 0.01 3.77 14.31 DOW JONES INDUS. AVG 13042.74 1.69 7.45 7.72 GBP/USD 2.0903 0.81 2.34 9.40 S&P 500 INDEX 1453.70 1.43 6.92 5.27 USD/JPY 110.69 1.75 5.92 6.26 NASDAQ COMPOSITE INDEX 2627.94 2.52 6.34 9.97 USD/CHF 1.1226 0.49 5.40 10.63 S&P/TSX COMPOSITE INDEX 13869.82 1.83 2.98 12.39 CARRY MEXICO BOLSA INDEX 29158.86 0.45 10.21 21.74 AUD/JPY 0.9115 1.67 1.49 18.86 BRAZIL BOVESPA STOCK IDX 64320.56 1.19 2.99 57.96 NZD/JPY 0.7641 1.53 0.10 14.73 DJ EURO STOXX 50 = Pr 4297.83 1.51 3.98 5.76 USD/CAD 0.9448 1.05 3.92 19.85 FTSE 100 INDEX 6304.90 1.21 6.33 1.55 RUBLE CAC 40 INDEX 5524.18 1.91 5.47 1.41 USD/RUB 24.4580 0.01 2.04 8.88 DAX INDEX 7812.40 0.09 2.85 22.88 EUR/RUB 35.9002 0.01 1.69 4.99 IBEX 35 INDEX 15731.20 1.35 3.08 12.35 EMERGING MARKETS S&P/MIB INDEX 37845.00 1.82 7.93 6.51 USD/TRY 1.2022 1.75 1.22 20.53 AMSTERDAM EXCH INDX 510.65 2.39 8.67 3.59 USD/MXN 10.8905 0.75 0.60 0.04 OMX STOCKHOLM 30 INDEX 1115.09 2.65 11.52 1.43 USD/BRL 1.7454 0.17 3.05 23.27 SWISS MARKET INDEX 8417.15 2.19 8.48 3.65 -

About US Global Investors

U.S. Global Investors Searching for Opportunities, Managing Risk History is Key to Future Success: Lessons Learned from Investment Cycles Jeffrey Hirsch, President of the Hirsch Organization Editor-in-Chief Stock Trader’s Almanac Editor Commodity Trader’s Almanac Frank Holmes, CEO and Chief Investment Officer U.S. Global Investors www.usfunds.com January 2012 1.800.US.FUNDS 11-772 Today’s Presenters Jeffrey Hirsch Frank Holmes www.usfunds.com January 2012 11-772 2 About U.S. Global Investors Publicly traded company, traded on NASDAQ (GROW) Headquartered in San Antonio, TX Boutique investment management firm specializing in commodity-related equity strategies Offers mutual funds focused in gold, precious metals and minerals, global resources, emerging markets and global infrastructure Manages $2.45 billion in average AUM as of September 30, 2011 www.usfunds.com January 2012 11-772 3 Focus on Education 28 MFEA STAR Awards for Excellence in Education www.usfunds.com January 2012 11-772 4 “Performance and Results Oriented” Investment leadership results in performance Winner of 29 Lipper performance awards, certificates and top rankings since 2000 (Four out of 13 U.S. Global Investors Funds received Lipper performance awards from 2005 to 2008, six out of 13 received certificates from 2000 to 2007, and two out of 13 received top rankings from 2009 to 2010.) www.usfunds.com January 2012 11-772 5 U.S. Global Investors Investment Process We use a matrix of “top-down” macro models and “bottom-up” micro stock selection models to determine weighting in countries, sectors and individual securities. We believe government policies are a precursor to change. -

Modulo: "Milano" Circa 3400 Strumenti (Lista Aggiornata Al 12/01/2021) Mercati Contenuti: Tutte Le Azioni Ed I Warrant

Modulo: "ITALIA" Circa 3500 strumenti (lista aggiornata al 03/09/2021) Mercati contenuti: Tutte le Azioni ed i Warrant quotati a Milano (Circa 700) Tutti gli ETF, ETC, ETN e QF quotati a Milano (Circa 1600) Selezione di Indici mondiali (Circa 850) Selezione di Futures (Circa 100) Selezione di Cross Valutari (Circa 180) Selezione di Criptovalute (Circa 30) AZIONI ITALIA (Circa 700) Nome 4AIM SICAF 4AIM SICAF COMPARTO 2 CROWDFUNDING A.B.P. NOCIVELLI A.S. ROMA A2A ABITARE IN ACEA ACQUAZZURRA ACSM ADIDAS ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES AEDES AEFFE AEGON AEROPORTO GUGLIELMO MARCONI DI BOLOGNA AGATOS AGEAS AHOLD DEL AIR FRANCE-KLM AIR LIQUIDE AIRBUS GROUP ALA ALERION ALFIO BARDOLLA ALGOWATT ALKEMY ALLIANZ ALMAWAVE ALPHABET CLASSE A ALPHABET CLASSE C AMAZON AMBIENTHESIS AMBROMOBILIARE AMGEN AMM AMPLIFON ANHEUSER-BUSCH ANIMA HOLDING ANTARES VISION APPLE AQUAFIL ARTERRA BIOSCIENCE ASCOPIAVE ASKOLL EVA ASML ASSITECA ASTALDI ASTM ATLANTIA ATON GREEN STORAGE AUTOGRILL AUTOSRADE MERID AVIO AXA AZIMUT B&C SPEAKERS B.F BANCA CARIGE BANCA FARMAFACTORING BANCA FINNAT BANCA GENERALI BANCA IFIS BANCA INTERMOBILIARE BANCA MEDIOLANUM BANCA MONTE PASCHI SIENA BANCA POPOLARE DI SONDRIO BANCA POPOLARE EMILIA ROMAGNA BANCA PROFILO BANCA SISTEMA BANCO BILBAO VIZCAYA ARGENTARIA (BBVA) BANCO BPM BANCO DESIO BANCO DESIO RNC BANCO DI SANTANDER BASF BASICNET BASTOGI BAYER BB BIO TECH BE BEGHELLI BEIERSDORF BFC MEDIA BIALETTI INDUSTRIE BIANCAMANO BIESSE BIOERA BLUE FINANCIAL COMMUNICATION BMW BNP PARIBAS BORGOSESIA BORGOSESIA RNC BREMBO BRIOSCHI BRUNELLO CUCINELLI BUZZI UNICEM -

Les Fusions-Acquisitions En Matière De Gaz Et De Pétrole Le Cas De L’Amérique Du Nord Albert Legault

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 15:27 Études internationales Les fusions-acquisitions en matière de gaz et de pétrole Le cas de l’Amérique du Nord Albert Legault Volume 35, numéro 3, septembre 2004 Résumé de l'article Cette étude vise à retracer l’évolution des F-A (fusions-acquisitions) en URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/009906ar Amérique du Nord, plus particulièrement en matière de gaz et de pétrole. Le DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/009906ar phénomène se situe dans la foulée de la restructuration des industries et dans le cadre d’une déréglementation généralisée de l’énergie, visant à encourager Aller au sommaire du numéro la concurrence sur un plan national et international. Dans un premier temps, nous tenterons de voir quelle est la part du secteur de l’énergie dans le cadre général des fusions-acquisitions, et de constater dans quelle mesure ces Éditeur(s) dernières correspondent ou non aux différents cycles d’évolution des prix en matière d’énergie. Dans un second temps, nous nous pencherons sur les IQHEI raisons et les motifs avancés pour justifier les F-A et tenterons de répondre aux trois questions suivantes. En se restructurant, l’industrie pétrolière a-t-elle ISSN réussi à accroître la valeur de ses entreprises, à faire profiter ses investissements, et à augmenter ses réserves ? Enfin, nous verrons quelles sont 0014-2123 (imprimé) les conséquences les plus immédiates des F-A sur l’industrie pétrolière au 1703-7891 (numérique) Canada. En effet, elle doit relever deux défis majeurs : comment rester compétitive, alors que les coûts de production augmentent, d’une part, et que le Découvrir la revue rendement sur les investissements tend à diminuer plutôt qu’à augmenter, d’autre part ? Citer cet article Legault, A. -

Exchange Listed Options

Directory EXCHANGE LISTED OPTIONS January 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS Options Listings: Equity Options .............................................................................. 2 LEAPS® (Long-Term Equity AnticiPation Securities®) ................ 51 Index Options ............................................................................. 64 Long-Term Index Options........................................................... 66 Currency Options........................................................................ 67 Long-Term Currency Options ..................................................... 68 Interest Rate Options ................................................................. 68 Long-Term Interest Rate Options............................................... 68 Index FLEX™ Options................................................................ 69 Equity FLEX™ Options .............................................................. 69 Footnotes.................................................................................... 84 Expiration Cycle Charts.............................................................. 85 Product Specifications: Equity Options ............................................................................ 86 LEAPS® (Long-Term Equity AnticiPation Securities®) ................ 86 Index Options ............................................................................. 87 Equity FLEX™ Options ............................................................ 123 Index FLEX™ Options.............................................................