ELEPHANT POPULATIONS in THAILAND Philip J. Storer"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taken for a Ride

Taken for a ride The conditions for elephants used in tourism in Asia Author Dr Jan Schmidt-Burbach graduated in veterinary medicine in Germany and completed a PhD on diagnosing health issues in Asian elephants. He has worked as a wild animal veterinarian, project manager and wildlife researcher in Asia for more than 10 years. Dr Schmidt-Burbach has published several scientific papers on the exploitation of wild animals as part of the illegal wildlife trade and conducted a 2010 study on wildlife entertainment in Thailand. He speaks at many expert forums about the urgent need to address the suffering of wild animals in captivity. Acknowledgment This report has only been possible with the invaluable help of those who have participated in the fieldwork, given advice and feedback. Thanks particularly to: Dr Jennifer Ford, Lindsay Hartley-Backhouse, Soham Mukherjee, Manoj Gautam, Tim Gorski, Dananjaya Karunaratna, Delphine Ronfot, Julie Middelkoop and Dr Neil D’Cruze. World Animal Protection is grateful for the generous support from TUI Care Foundation and The Intrepid Foundation, which made this report possible. Preface Contents World Animal Protection has been moving the world to protect animals for more than 50 years. Currently working in over Executive summary 6 50 countries and on 6 continents, it is a truly global organisation. Protecting the world’s wildlife from exploitation and cruelty is central to its work. Introduction 8 The Wildlife - not entertainers campaign aims to end the suffering of hundreds of thousands of wild animals used and abused Background information 10 in the tourism entertainment industry. The strength of the campaign is in building a movement to protect wildlife. -

Thai Tourist Industry 'Driving' Elephant Smuggling 2 March 2013, by Amelie Bottollier-Depois

Thai tourist industry 'driving' elephant smuggling 2 March 2013, by Amelie Bottollier-Depois elephants for the amusement of tourists. Conservation activists accuse the industry of using illicitly-acquired animals to supplement its legal supply, with wild elephants caught in Myanmar and sold across the border into one of around 150 camps. "Even the so-called rescue charities are trying to buy elephants," said John Roberts of the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation. Domestic elephants in Thailand—where the pachyderm is a national symbol—have been employed en masse in the tourist trade since they An elephant performs for tourists during a show in found themselves unemployed in 1989 when Pattaya, on March 1, 2013. Smuggling the world's logging was banned. largest land animal across an international border sounds like a mammoth undertaking, but activists say Just 2,000 of the animals remain in the wild. that does not stop traffickers supplying Asian elephants to Thai tourist attractions. Prices have exploded with elephants now commanding between 500,000 and two million baht ($17,000 to $67,000) per baby, estimates suggest. Smuggling the world's largest land animal across an international border sounds like a mammoth undertaking, but activists say that does not stop traffickers supplying Asian elephants to Thai tourist attractions. Unlike their heavily-poached African cousins—whose plight is set to dominate Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) talks in Bangkok next week—Asian elephants do not often make the headlines. But the species is also under threat, as networks operate a rapacious trade in wild elephants to meet the demands of Thailand's tourist industry. -

Sukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS

UttaraditSukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS SUKHOTHAI 8 City Attractions 9 Special Events 21 Local Products 22 How to Get There 22 UTTARADIT 24 City Attractions 25 Out-Of-City Attractions 25 Special Events 29 Local Products 29 How to Get There 29 PHITSANULOK 30 City Attractions 31 Out-Of-City Attractions 33 Special Events 36 Local Products 36 How to Get There 36 PHETCHABUN 38 City Attractions 39 Out-Of-City Attractions 39 Special Events 41 Local Products 43 How to Get There 43 Sukhothai Sukhothai Uttaradit Phitsanulok Phetchabun Phra Achana, , Wat Si Chum SUKHOTHAI Sukhothai is located on the lower edge of the northern region, with the provincial capital situated some 450 kms. north of Bangkok and some 350 kms. south of Chiang Mai. The province covers an area of 6,596 sq. kms. and is above all noted as the centre of the legendary Kingdom of Sukhothai, with major historical remains at Sukhothai and Si Satchanalai. Its main natural attraction is Ramkhamhaeng National Park, which is also known as ‘Khao Luang’. The provincial capital, sometimes called New Sukhothai, is a small town lying on the Yom River whose main business is serving tourists who visit the Sangkhalok Museum nearby Sukhothai Historical Park. CITY ATTRACTIONS Ramkhamhaeng National Park (Khao Luang) Phra Mae Ya Shrine Covering the area of Amphoe Ban Dan Lan Situated in front of the City Hall, the Shrine Hoi, Amphoe Khiri Mat, and Amphoe Mueang houses the Phra Mae Ya figure, in ancient of Sukhothai Province, this park is a natural queen’s dress, said to have been made by King park with historical significance. -

“White Elephant” the King's Auspicious Animal

แนวทางการบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีนส าหรับโรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) สังกัดกรุงเทพมหานคร ประกอบด้วยองค์ประกอบหลักที่ส าคัญ 4 องค์ประกอบ ได้แก่ 1) เป้าหมายและ หลักการ 2) หลักสูตรและสื่อการสอน 3) เทคนิคและวิธีการสอน และ 4) การพัฒนาผู้สอนและผู้เรียน ค าส าคัญ: แนวทาง, การบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีน, โรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) Abstract This study aimed to develop a guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. The study was divided into 2 phases. Phase 1 was to investigate the present state and needs on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration from the perspectives of the involved personnel in Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Phase 2 was to create guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and to verify the accuracy and suitability of the guidelines by interviewing experts on teaching Chinese language and school management. A questionnaire, a semi-structured interview form, and an evaluation form were used as tools for collecting data. Percentage, mean, and Standard Deviation were employed for analyzing quantitative data. Modified Priority Needs Index (PNImodified) and content analysis were used for needs assessment and analyzing qualitative data, respectively. The results of this research found that the actual state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in all aspects was at a high level ( x =4.00) and the expected state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in the overall was at the highest level ( x =4.62). The difference between the actual state and the expected state were significant different at .01 level. -

Mr. Cholathorn Chamnankid

Thailand ASEAN Heritage Parks Mr. Cholathorn Chamnankid Director of National Parks Research and Innovation Development Division National Parks office, DNP ⚫PAs Of TH ⚫AHP in TH ⚫ Khao Yai NP (1984) No. 10 ⚫ Tarutao NP (1984) No. 11 ⚫ Mo Ko Surin-Mo Ko Similan-Ao Phang-nga NP Complex (2003) No. 22 ⚫ Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex (2003) No. 23 ⚫AHP in TH 2019 Content ⚫ Hat Chao Mai NP and Mo Ko Libong Non-hunting Area (2019) No. 45 ⚫ Mu Koh Ang Thong NP (2019) No. 46 ⚫AHP Country Reports ⚫Purpose in TH (2020-2025) Protected Area of Thailand สาธารณรัฐประชาธิปไตยประชาชนลาว 1. Pai Watershed – Salawin Forest14 . Khlong Saeng-khao Sok Complex Forest Complex 2. Sri Lanna - Khun Tan Forest 15. Khao Luang Forest Complex เมยี นมาร์ Complex 16. Khao Banthat Forest 3. Doi Phu Kha - Mae Yom Forest Complex Complex กัมพูชา 17. Hala Bala Forest ประชาธิปไตย 4. Mae Ping – Om Goi Forest Complex Complex 18. Mu Ko Similan –Phi Phi - Andaman อา่ วไทย 5. Phu Miang - Phu Thong Forest Complex 19. Mu Ko Ang Thong-gulf of Thailand 6. Phu Khiao – Nam Nao Forest 7. Phu Phan Forest Complex 8. Phanom Dong Rak-pha Taem Forest Complex อุทยานแห่งชาติ 9. Dong Phayayen Khao Yai Forest มาเลเซีย เขตรกั ษาพนั ธุส์ ัตวป์ ่า Complex 10. Eastern Forest Complex PAs TH Category No. Area % of country (sq km) area National Park 133 63,532.49 12.38 Forest Park 94 1,164 0.22 Wildlife Sanctuary 60 37377.12 7.2 Non-hunting Area 80 5,736.36 1.11 Botanical Garden 16 49.44 0.009 Arboretum 55 40.67 0.007 Biosphere Reserve 4 216 0.05 Proposed PAs 22 6402.24 1.25 Total 114,518.32 22.26 Thailand and International Protected Areas Conservation Mechanisms Year ratified Convention Remarks CITES 1983 WHC 1987 2 Natural & 3 Cultural WH sites RAMSAR 1998 14 internationally recognized wetlands CBD 2003 UNFCCC 1995 AHP 1984 Khao Yai NP, Tarutao MNP, Kaeng Kracharn Forest Complex, Surin & Similan MNPs, Ao Phangnga Complex, Hat Chao Mai - Mu Koh Libong, Mu Ko Ang Thong Marine National Park ▪AHP in TH 1. -

Non-Panthera Cats in South-East Asia Tantipisanuh Et Al

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 8 | SPRING 2014 Non-CATPanthera cats in newsSouth-east Asia 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guest Editors: J. W. Duckworth Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Antony Lynam This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Cover Photo: Non-Panthera cats of South-east Asia: from the Taiwan Council of Agriculture’s Forestry Bureau, Zoo Leipzig and From top centre clock-wise the Wild Cat Club. jungle cat (Photo K. Shekhar) clouded leopard (WCS Thailand Prg) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh fishing cat (P. Cutter) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser, Jonas Bach leopard cat (WCS Malaysia Prg) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Asiatic golden cat (WCS Malaysia Prg) marbled cat (K. Jenks) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

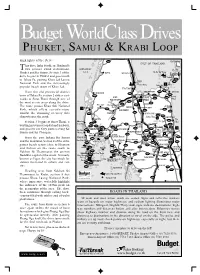

Phuket &Krabi Loop

Budget WorldClass Drives PHUKET, SAMUI & KRABI LOOP Highlights of the Drive 4006 KO PHANGAN G U L F O F T H A I L A N D his drive links Southern Thailand’s T two premier island destinations, A N D A M A N Ban Chaweng Mu Ko Ang Thong Phuket and Ko Samui. Section 1 of the S E A KAPOE THA CHANA KO SAMUI drive begins in Phuket and goes north Ban Nathon to Takua Pa, passing Khao Lak Lamru 4169 CHAIYA 4170 National Park and the increasingly Phum Riang 4 Ferry popular beach resort of Khao Lak. DON SAK THA CHANG 4142 From the old provincial district KANCHANADIT 4142 KHANOM KURA BURI 41 PHUNPHIN 4232 town of Takua Pa, section 2 strikes east- 4 401 4014 Hat Nai KHIRI SURAT 4010 wards to Surat Thani through one of RATTANIKHOM THANI Phlao 401 3 the most scenic areas along the drive. 4134 4100 Khao Sok Rachaphrapha 41 The route passes Khao Sok National KHIAN SA SICHON TAKUA PA Dam SAN NA DOEM 2 401 4106 Park, which offers eco-adventure BAN TAKHUN 4009 401 4133 amidst the stunning scenery that 4032 PHANOM BAN NA SAN 4188 4186 characterises the park. Krung Ching NOPPHITAM KAPONG 415 4140 THA Khao Lak WIANG SA (roads closed) SALA Section 3 begins at Surat Thani, a 4090 Lam Ru 4035 PHRA PHIPUN 4141 bustling provincial capital and harbour, 4240 4090 PHLAI PHRAYA 4016 4 4197 SAENG PHROMKHIRI 4013 4133 4015 5 and goes to car-ferry ports serving Ko 4 PHANG NGA 4035 CHAI BURI NAKHON SRI Hat Thai THAP PHUT 4228 Khao Samui and Ko Phangan. -

Hua Hin Beach

Cover_m14.indd 1 3/4/20 21:16 Hua Hin Beach 2-43_m14.indd 2 3/24/20 11:28 CONTENTS HUA HIN 8 City Attractions 9 Activities 15 How to Get There 16 Special Event 16 PRACHUAP KHIRI KHAN 18 City Attractions 19 Out-Of-City Attractions 19 Local Products 23 How to Get There 23 CHA-AM 24 Attractions 25 How to Get There 25 PHETCHABURI 28 City Attractions 29 Out-Of-City Attractions 32 Special Events 34 Local Products 35 How to Get There 35 RATCHABURI 36 City Attractions 37 Out-Of-City Attractions 37 Local Products 43 How to Get There 43 2-43_m14.indd 3 3/24/20 11:28 HUA HIN & CHA-AM HUA HIN & CHA-AM Prachuap Khiri Khan Phetchaburi Ratchaburi 2-43_m14.indd 4 3/24/20 11:28 2-43_m14.indd 5 3/24/20 11:28 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Kingdom of Cambodia 2-43_m14.indd 6 3/24/20 11:28 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Kingdom of Cambodia 2-43_m14.indd 7 3/24/20 11:28 Hat Hua Hin HUA HIN 2-43_m14.indd 8 3/24/20 11:28 Hua Hin is one of Thailand’s most popular sea- runs from a rocky headland which separates side resorts among overseas visitors as well as from a tiny shing pier, and gently curves for Thais. Hua Hin, is located 281 kiometres south some three kilometres to the south where the of Bangkok or around three-hour for driving a Giant Standing Buddha Sculpture is located at car to go there. -

Arana John.Pdf

48056307: MAJOR: ARCIIlTECTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT AND TOURISM KEYWORD: SITE DIAGNOSTIC, NATURAL HERITAGE, KHAO YA!, DONG PHAY A YEN KHAO Y Al FOREST COMPLEX. JOHN ARANA: SITE DIAGNOSTIC AND VISITOR FACILITIES IMPROVEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS, AT THE KHAO YA! NATIONAL PARK. RESEARCH PROJECT ADVISOR: ASST.PROF. DEN WASIKSIRI, 143 pp. Khao Yai is Thailand's first and best known national park. It contains a wealth of natural attractions: Flora, Fauna, Vistas and waterfalls. The park was established in 1962 and is currently managed by National Parle, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department. Khao Yai has been declared a world heritage site as part of the Dong Phayayen Khao Yai Forest Complex under criterion (IV) in 2005 and was also previously declared an Association of South East Asian Nation (ASEAN) heritage pad. in I 984. This research project attempts to increase understanding of the park, raise awareness regarding the condition of park tourism infrastructure and assist in future decision making process by providing a visitor's perspective. The most recent management plan for Khao Yai National Park 2007-2017 has not been received with enthusiasm. In this study the author encourages the review of the management plan, updating of master plan and the use of best practice guidelines for park management. It is hoped that the document contributes positively to park. management and visitors. Architectural Heritage Management wtd Tourism Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2006 Student's signature .. ~ .. \: ....~ .......... .. R hPr. Ad. ' . ~/ esearc qiect vISOr s signature ......... 1 ..... k .••.............................. ' ~ C ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The realization of this research project can be attributed to the extensive support and assistance from my advisor, Assistant Professor Den Wasiksiri and Professor Dr. -

Khao Yai National Park

Khao Yai National Park Khao Yai National Park was established as the first national park of Thailand in 1962. The national park covers a total area of 2,165.55 square kilometres in the four provinces of Nakhon Nayok, Prachin Buri, Nakhon Ratchasima and Saraburi. Consisting of large forested areas, scenic beauty and biological diversity, Khao Yai National Park, together with other protected areas within the Dong Phaya Yen mountain range, are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Khao Yai or çBig Mountainé is home to a great diversity of flora and fauna, as well as pure beautiful nature. Geography A rugged mountain range dominates most areas of the park. Khao Rom is the highest peak towering at 1,351 metres above mean sea level. The region is the source of five main rivers, the Prachin Buri, acuminata, Vatica odorata, Shorea henryana, Hopea Nakhon Nayok, Lam Ta Khong, Lam Phra Phloeng ferrea, Tetrameles nudiflora, Pterocymbium tinctorium and Muak Lek stream. and Nephelium hypoleucum. Such rich wilderness is home to a large amount of Climate wildlife such as Asian Elephant, Northern Red Muntjac, The weather is warm all year round with an Sambar, Tiger, Guar, Southwest China Serow, Bears, average temperature of 23 degree Celsius. Porcupines, Gibbons, Black Giant Squirrel, Small Indian Civet and Common Palm Civet. Flora and Fauna There are over 200 bird species, including Great Mixed deciduous forest occupies the northern part Hornbill, Wreathed Hornbill, Tickell's Brown Hornbill, of the park with elevations ranging between 200-600 Hill Myna, Blue Magpie, Scarlet Minivet, Blue Pitta, metres. -

Reiseplanung Reiseziele in Thailand

REISEPLANUNG REISEZIELE IN THAILAND Willkommen in Thailand. .6 BANGKOK& ZENTRAL Thailands Top 20 10 UMGEBUNG 56 THAILAND 163 Gut zu wissen 22 Sehenswertes 57 Ayutthaya 166 Thailand für Aktivitäten 87 Lopburi 176 Einsteiger 24 Feste & Events 102 Kanchanaburi 182 Was gibt's Neues? 26 Schlafen 103 Khao Laem National Park 195 Wie wär's mit 27 Essen 117 Ausgehen & Nachtleben. 129 Si Nakharin Monat für Monat 29 National Park 195 Unterhaltung 134 Reiserouten 32 Chaloem Ratanakosin Shoppen 139 National Park 196 Essen & trinken KoKret 159 wie die Thais 38 Thong Pha Phum Amphawa 160 National Park 197 Für jeden der richtige Strand 42 Nakhon Pathom 161 Sangkhlaburi 197 Mit Kindern reisen 48 Thailand im Überblick.. 52 http://d-nb.info/1057892696 KOCHANG& PROVINZ Provinz Tak 400 OSTKÜSTE 202 CHIANG MAI 248 Mae Sot 401 Si Racha 203 ChiangMai 249 Um Phang & Umgebung.406 Ko Si Chang 207 Nördliches Chiang Provinz Mae Hong Pattaya 209 Mai 302 Son 411 Rayong 216 Mae-Sa-Tal & Pai 411 Samoeng 302 Ban Phe 216 Soppong 421 Chiang Dao 304 KoSamet 217 Mae Hong Son 424 Doi Ang Khang 307 Chanthaburi 222 KhunYuam 433 Fang &Tha Ton 308 Trat 226 Mae Sariang 435 Südliches Chiang Salawin National Park.. .438 Ko Chang 230 Mai 310 Mae Sam Laep 438 KoWai 243 Bo Sang 310 KoMak 244 San Kamphaeng 310 NORDOST KoKut 246 Mae Kampong 311 THAILAND 439 Hang Dong & Ban Thawai 312 Nakhon Ratchasima (Khorat) 443 Doi Inthanon ' National Park 313 Phimai 450 Khao Yai National Park...452 NORD Nang Rong 456 THAILAND 315 Geschichtspark PhanomRung 457 Lamphun 318 Surin 460 Doi Khun Tan National Park 321 Si Saket 465 Lampang 321 Ubon Ratchathani 465 Chiang Rai 330 Khon Kaen 477 Mae Salong (Santikhiri) .340 UdonThani 487 MaeSai 344 Nong Khai 494 DoiTung 348 Loei 504 Chiang Saen 349 Chiang Khan 507 Sop Ruak 352 Phu Ruea National Park. -

Elephant Bibliography Elephant Editors

Elephant Volume 2 | Issue 3 Article 17 12-20-1987 Elephant Bibliography Elephant Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/elephant Recommended Citation Shoshani, J. (Ed.). (1987). Elephant Bibliography. Elephant, 2(3), 123-143. Doi: 10.22237/elephant/1521732144 This Elephant Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Elephant by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Fall 1987 ELEPHANT BIBLIOGRAPHY: 1980 - PRESENT 123 ELEPHANT BIBLIOGRAPHY With the publication of this issue we have on file references for the past 68 years, with a total of 2446 references. Because of the technical problems and lack of time, we are publishing only references for 1980-1987; the rest (1920-1987) will appear at a later date. The references listed below were retrieved from different sources: Recent Literature of Mammalogy (published by the American Society of Mammalogists), Computer Bibliographic Search Services (CCBS, the same used in previous issues), books in our office, EIG questionnaires, publications and other literature crossing the editors' desks. This Bibliography does not include references listed in the Bibliographies of previous issues of Elephant. A total of 217 new references has been added in this issue. Most of the references were compiled on a computer using a special program developed by Gary L. King; the efforts of the King family have been invaluable. The references retrieved from the computer search may have been slightly altered. These alterations may be in the author's own title, hyphenation and word segmentation or translation into English of foreign titles.