Tribes in Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tor Yemen Nutrition Cluster Revi

Yemen Nutrition Cluster كتله التغذية اليمن https://www.humanitarianresponse.info https://www.humanitarianresponse.info /en/operations/yemen/nutrition /en/operations/yemen/nutrition XXXXXXXX XXXXXXXX YEMEN NUTRITION CLUSTER TERMS OF REFERENCE Updated 23 April 2018 1. Background Information: The ‘Cluster Approach1’ was adopted by the interagency standing committee as a key strategy to establish coordination and cooperation among humanitarian actors to achieve more coherent and effective humanitarian response. At the country level, the aim is to establish clear leadership and accountability for international response in each sector and to provide a framework for effective partnership and to facilitat strong linkages among international organization, national authorities, national civil society and other stakeholders. The cluster is meant to strengthen rather than to replace the existing coordination structure. In September 2005, IASC Principals agreed to designate global Cluster Lead Agencies (CLA) in critical programme and operational areas. UNICEF was designated as the Global Nutrition Cluster Lead Agency (CLA). The nutrition cluster approach was adopted and initiated in Yemen in August 2009, immediately after the break-out of the sixth war between government forces and the Houthis in Sa’ada governorate in northern Yemen. Since then Yemen has continued to face complex emergencies that are largely conflict-generated and in part aggravated by civil unrest and political instability. These complex emergencies have come on the top of an already fragile situation with widespread poverty, food insecurity and underdeveloped infrastructure. Since mid-March 2015, conflict has spread to 20 of Yemen’s 22 governorates, prompting a large-scale protection crisis and aggravating an already dire humanitarian crisis brought on by years of poverty, poor governance and ongoing instability. -

View / Download 7.3 Mb

Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Janice Hyeju Jeong 2019 Abstract While China’s recent Belt and the Road Initiative and its expansion across Eurasia is garnering public and scholarly attention, this dissertation recasts the space of Eurasia as one connected through historic Islamic networks between Mecca and China. Specifically, I show that eruptions of -

Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen's Red Sea Coast

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2017 “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. GINGKO LIBRARY ART SERIES Senior Editor: Melanie Gibson Architectural Heritage of Yemen Buildings that Fill my Eye Edited by Trevor H.J. Marchand First published in 2017 by Gingko Library 70 Cadogan Place, London SW1X 9AH Copyright © 2017 selection and editorial material, Trevor H. J. Marchand; individual chapters, the contributors. The rights of Trevor H. J. Marchand to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the individual authors as authors of their contributions, has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Yemen's Salafi Network(S): Mortgaging the Country's Future

VERSUS Workshop 4 July 2019 — 1st Draft Yemen’s Salafi Network(s): Mortgaging the Country’s Future Thanos Petouris Introduction The takeover of the Yemeni capital Sanaʿa by the Huthi forces in September 2014 and their subsequent coup of February 2015 that led to the ousting of the incumbent president ʿAbd Rabbu Mansur Hadi and his government signify the beginning of the current Yemeni civil war. The restoration of president Hadi’s rule is also the ostensible primary aim of the direct military intervention by the Saudi and Emirati-led Arab coalition forces, which is also intent on defeating the Huthi movement. The rise of the Huthis, or Ansar Allah as they call themselves, has been inextricably linked with the rise and activities of Salafi activists in the northern Yemeni heartland of the Zaydi Shiʿa sect and has been depicted as a response, in part, both to the doctrinal challenge and social pressure exerted over the Zaydi community by Salafism.1 Since the beginning of the Yemeni civil war Salafi militiamen, either individually or as leaders of larger groups, have participated in numerous military operations mostly under the control of the Arab coalition forces.2 Their active involvement in the conflict marks a significant departure from the doctrinal tenets of Yemeni Salafism, which are generally characterised by a reluctance for participation in the politics of the land.3 Today, more than four years into the conflict, what can be termed as Yemen’s Salafi Network is conspicuous by its established presence both within local political movements (Southern Transitional Council; hereafter STC), and as part of coalition-led military units (Security Belt forces, local Elite forces, Giants Brigades etc). -

On Conservation and Development: the Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen*

On Conservation and Development: The Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen* Deepa Mehta Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation** Columbia University in the City of New York New York, NY 10027, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT A study of small and medium enterprises that make up the highly specialized mud brick construction industry in southern Yemen reveals how the practice has been sustained through closely-linked regional production chains and strong firm inter-relationships. Yemen, as it struggles to grow as a nation, has the potential to gain from examining the contribution that these institutions make to an ancient building practice that still continues to provide jobs and train new skilled workers. The impact of these firms can be bolstered through formal recognition and capacity development. UNESCO, ICOMOS, and other conservation agencies active in the region provide a model that emphasizes architectural conservation as well as the concurrent development of the existing socioeconomic linkages. The primary challenge is that mud brick construction is considered obsolete, but evidence shows that the underlying institutions are resilient and sustainable, and can potentially provide positive regional policy implications. Key Words: conservation, planning, development, informal sector, capacity building, Yemen, mud brick construction. * Paper prepared for GLOBELICS 2009: Inclusive Growth, Innovation and Technological Change: education, social capital and sustainable development, October 6th – -

Tribes and Politics in Yemen

Arabian Peninsula Background Notes APBN-007 December 2008 Tribes and Politics in Yemen Yemen’s government is not a tribal regime. The Tribal Nature of Yemen Yet tribalism pervades Yemeni society and influences and limits Yemeni politics. The ‘Ali Yemen, perhaps more than any other state ‘Abdullah Salih regime depends essentially on in the Arab world, is fundamentally a tribal only two tribes, although it can expect to rely society and nation. To a very large degree, on the tribally dominated military and security social standing in Yemen is defined by tribal forces in general. But tribesmen in these membership. The tribesman is the norm of institutions are likely to be motivated by career society. Other Yemenis either hold a roughly considerations as much or more than tribal equal status to the tribesman, for example, the identity. Some shaykhs also serve as officers sayyids and the qadi families, or they are but their control over their own tribes is often inferior, such as the muzayyins and the suspect. Many tribes oppose the government akhdam. The tribes in Yemen hold far greater in general on grounds of autonomy and self- importance vis-à-vis the state than elsewhere interest. The Republic of Yemen (ROY) and continue to challenge the state on various government can expect to face tribal resistance levels. At the same time, a broad swath of to its authority if it moves aggressively or central Yemen below the Zaydi-Shafi‘i divide – inappropriately in both north and south. But including the highlands north and south of it should be stressed that tribal attitudes do Ta‘izz and in the Tihamah coastal plain – not differ fundamentally from the attitudes of consists of a more peasantized society where other Yemenis and that tribes often seek to tribal ties and reliance is muted. -

Download File

Yemen Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Yemen/2019/Mahmoud Fadhel Reporting Period: 1 - 31 October 2019 Highlights Situation in Numbers • In October, 3 children were killed, 16 children were injured and 3 12.3 million children in need of boys were recruited by various parties to the conflict. humanitarian assistance • 59,297 suspected Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD)/cholera cases were identified and 50 associated deaths were recorded (0.08 case 24.1 million fatality rate) in October. UNICEF treated over 14,000 AWD/cholera people in need suspected cases (one quarter of the national caseload). (OCHA, 2019 Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview) • Due to fuel crisis, in Ibb, Dhamar and Al Mahwit, home to around 400,000 people, central water systems were forced to shut down 1.71 million completely. children internally displaced • 3.1 million children under five were screened for malnutrition, and (IDPs) 243,728 children with Severe Acute Malnutrition (76 per cent of annual target) admitted for treatment. UNICEF Appeal 2019 UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status US$ 536 million Funding Available* SAM Admission 76% US$ 362 million Funding status 68% Nutrition Measles Rubella Vaccination 91% Health Funding status 77% People with drinking water 100% WASH Funding status 64% People with Mine Risk Education 82% Child Funding status 40% Protection Children with Access to Education 29% Funding status 76% Education People with Social Economic 61% Assistance Policy Social Funding status 38% People reached with C4D efforts 100% *Funds available includes funding received for the current C4D Funding status 98% appeal (emergency and other resources), the carry- forward from the previous year and additional funding Displaced People with RRM Kits 59% which is not emergency specific but will partly contribute towards 2019 HPM results. -

Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12Th AH/18Th CE Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah Al-Dihlawi

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Islamic economic thinking in the 12th AH/18th CE century with special reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75432/ MPRA Paper No. 75432, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:58 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Center King Abdulaziz University http://spc.kau.edu.sa FOREWORD The Islamic Economics Research Center has great pleasure in presenting th Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12th AH (corresponding 18 CE) Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi). The author, Professor Abdul Azim Islahi, is a well-known specialist in the history of Islamic economic thought. In this respect, we have already published his following works: Contributions of Muslim Scholars to th Economic Thought and Analysis up to the 15 Century; Muslim th Economic Thinking and Institutions in the 16 Century, and A Study on th Muslim Economic Thinking in the 17 Century. The present work and the previous series have filled, to an extent, the gap currently existing in the study of the history of Islamic economic thought. In this study, Dr. Islahi has explored the economic ideas of Shehu Uthman dan Fodio of West Africa, a region generally neglected by researchers. He has also investigated the economic ideas of Shaykh Muhammad b. Abd al-Wahhab, who is commonly known as a religious renovator. Perhaps it would be a revelation for many to know that his economic ideas too had a role in his reformative endeavours. -

Situation of Human Rights in Yemen, Including Violations and Abuses Since September 2014

United Nations A/HRC/39/43* General Assembly Distr.: General 17 August 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-ninth session 10–28 September 2018 Agenda items 2 and 10 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Technical assistance and capacity-building Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights containing the findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts and a summary of technical assistance provided by the Office of the High Commissioner to the National Commission of Inquiry** Summary The present report is being submitted to the Human Rights Council in accordance with Council resolution 36/31. Part I of the report contains the findings, conclusions and recommendations of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen. Part II provides an account of the technical assistance provided by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to the National Commission of Inquiry into abuses and violations of human rights in Yemen. * Reissued for technical reasons on 27 September 2018. ** The annexes to the present report are circulated as received, in the language of submission only. GE.18-13655(E) A/HRC/39/43 Contents Page I. Findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen ....................... 3 A. Introduction and mandate .................................................................................................... -

Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study: Market Functionality and Community Perception of Cash Based Assistance

INTER-AGENCY JOINT CASH STUDY: MARKET FUNCTIONALITY AND COMMUNITY PERCEPTION OF CASH BASED ASSISTANCE YEMEN REPORT DECEMBER 2017 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 Cash and Market Working Group Partners The following organisations contributed to the production of this report, as members of the Cash and Market Working Group for Yemen (CMWG) 1 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 Cover Image: OCHA/ Charlotte Cans, Sana’a, June 2015. https://ocha.smugmug.com/Countries/Yemen/General-views-Sanaa/i-CrmGpCB About REACH REACH facilitates the development of information tools and products that enhance the capacity of aid actors to make evidence-based decisions in emergency, recovery and development contexts. All REACH activities are conducted through inter-agency aid coordination mechanisms. For more information, you can write to our in-country office: [email protected]. You can view all our reports, maps and factsheets on our resource centre: reachresourcecentre.info, visit our website at reach-initiative.org, and follow us @REACH_info 2 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 SUMMARY Since 2015, conflict in Yemen has left 3 million people displaced and over half of the population food insecure, and has destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure1. As of July 2017, much of the population had lost their primary source of income, 46% lacked access to a free improved water source2, and an outbreak of cholera had become the largest in modern history.3 The Cash and Market Working Group (CMWG) estimated that in 2016, cash transfer programmes were conducted in 22 governorates across Yemen; however, it found little evidence to determine which method of financial assistance is the most suitable in the context of Yemen. -

The Theory of Punishment in Islamic Law a Comparative

THE THEORY OF PUNISHMENT IN ISLAMIC LAW A COMPARATIVE STUDY by MOHAMED 'ABDALLA SELIM EL-AWA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Law March 1972 ProQuest Number: 11010612 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010612 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 , ABSTRACT This thesis deals with the theory of Punishment in Islamic law. It is divided into four ch pters. In the first chapter I deal with the fixed punishments or Mal hududrl; four punishments are discussed: the punishments for theft, armed robbery, adultery and slanderous allegations of unchastity. The other two punishments which are usually classified as "hudud11, i.e. the punishments for wine-drinking and apostasy are dealt with in the second chapter. The idea that they are not punishments of "hudud11 is fully ex- plained. Neither of these two punishments was fixed in definite terms in the Qurfan or the Sunna? therefore the traditional classification of both of then cannot be accepted. -

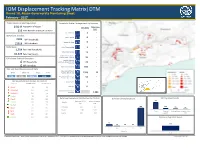

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017 Total Governorate Population Household Shelter Arrangements by Location 2 Population of Abyan 1 0.56 M IDPs (HH) Returnees (HH) 116 Total Number of Unique Locations School Buildings 2 - IDPs from Conflict Health Facilities 0 - 2103 IDP Households Religious Buildings 0 - 12618 IDP Individuals Returnees Other Private Building 5 - 1,754 Returnee Households Other Public Building 15 - 10,524 Returnee Persons Settlements (Grouped of Families) Urban and Rural - IDPs from Natural Disasters 24 Isolated/ dispersed IDP Households settlements (detatched from 26 - 0 a location) IDP Individuals 0 Rented Accomodation 650 - Sex and Age Dissagregated Data Host Families Who are Men Women Boys Girls Relatives (no rent fee) 1326 70 21% 23% 25% 31% Host Families Who are not Relatives (no rent fee) 54 - IDP Household Distribution Per District Second Home 1 - District IDP HH in Jan IDP HH in Feb Ahwar 32 29 Unknown 0 - Al Mahfad 379 264 Original House of Habitual Al Wade'a 110 96 Residence 1,684 Jayshan 15 25 Khanfir 505 499 Returnee Household Distribution Per District Duration of Displacement IDP Top Most Needs Returnee HH in Returnee HH in 79% Lawdar 259 278 District Jan Feb Mudiyah 34 35 Al Wade'a 130 130 92% 12% 6% Rasad 241 201 2% Khanfir 1,200 1,200 Sarar 121 114 Food Financial Drinking Water Household Items Lawdar 424 424 support (NFI) Sibah 248 221 Zingibar 221 341 Returnee Top Most Needs 8% 0% 0% 0% 100% 1-3 4-6 7-9 10-12 12 > Months Food 1 Population