The Museum As Artifact by Jayne Merkel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Abuse of Architectonics by Decorating in an Era After Deconstructivism

THE ABUSE OF ARCHITECTONICS BY DECORATING IN AN ERA AFTER DECONSTRUCTIVISM DECONSTRUCTION OF THE TECTONIC STRUCTURE AS A WAY OF DECORATION PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 MSC3 | INTERIORS, BUILDINGS, CITIES | STUDIO BACK TO SCHOOL AR0830 ARCHITECTURE THEORY | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | GRADUATION THESIS FALL SEMESTER 2008-2009 | MARCH 09 THESIS | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | AR0830 | PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 | MAR-09 | P. 1 ‘In fact, all architecture proceeds from structure, and the first condition at which it should aim is to make the outward form accord with that structure.’ 1 Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1872) Lectures Everything depends upon how one sets it to work… little by little we modify the terrain of our work and thereby produce new configurations… it is essential, systematic, and theoretical. And this in no way minimizes the necessity and relative importance of certain breaks of appearance and definition of new structures…’ 2 Jacques Derrida (1972) Positions ‘It is ironic that the work of Coop Himmelblau, and of other deconstructive architects, often turns out to demand far more structural ingenuity than works developed with a ‘rational’ approach to structure.’ 3 Adrian Forty (2000) Words and Buildings Theme In recent work of architects known as deconstructivists the tectonic structure of the buildings seems to be ‘deconstructed’ in order to decorate the building’s image. In other words: nowadays deconstruction has become a style with the architectonic structure used as decoration. Is the show of architectonic elements in recent work of -

Press Release Frank Gehry First Major European

1st August 2014 PRESS RELEASE communications and partnerships department 75191 Paris cedex 04 FRANK GEHRY director Benoît Parayre telephone FIRST MAJOR EUROPEAN 00 33 (0)1 44 78 12 87 e-mail [email protected] RETROSPECTIVE press officer 8 OCTOBER 2014 - 26 JANUARY 2015 Anne-Marie Pereira telephone GALERIE SUD, LEVEL 1 00 33 (0)1 44 78 40 69 e-mail [email protected] www.centrepompidou.fr For the first time in Europe, the Centre Pompidou is to present a comprehensive retrospective of the work of Frank Gehry, one of the great figures of contemporary architecture. Known all over the world for his buildings, many of which have attained iconic status, Frank Gehry has revolutionised architecture’s aesthetics, its social and cultural role, and its relationship to the city. It was in Los Angeles, in the early 1960s, that Gehry opened his own office as an architect. There he engaged with the California art scene, becoming friends with artists such as Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Bell, and Ron Davis. His encounter with the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns would open the way to a transformation of his practice as an architect, for which his own, now world-famous, house at Santa Monica would serve as a manifesto. Frank Gehry’s work has since then been based on the interrogation of architecture’s means of expression, a process that has brought with it new methods of design and a new approach to materials, with for example the use of such “poor” materials as cardboard, sheet steel and industrial wire mesh. -

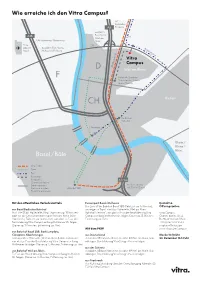

Anfahrt DE.Pdf

Wie erreiche ich den Vitra Campus? A5 Karlsruhe / A5 Freiburg Ausfahrt / Exit / Sortie A35 B3 Weil am A35 Strassburg / Strasbourg Rhein Euro E35 Airport Ausfahrt / Exit / Sortie Rö Basel Mulhouse / Freiburg me rstras se Vitra Campus Müllheimer Str. Bahnhof / Zentrum Train station / Centre Gare / Centre Badischer Bahnhof Claraplatz 55 Rhein / Rhine / Rhin Basel / Bâle Zug / Train Tram Bus Fussweg / Footpath / A2/A3 Chemin pédestre 8 2 Landesgrenze / A2 Bern / Berne National border / Bahnhof SBB A3 Zürich / Zurich Frontière nationale Mit den öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln Euroairport Basel/Mulhouse Kontakt & Bus Linie 50 bis Bahnhof Basel SBB (Fahrtzeit ca. 15 Minuten), Öffnungszeiten von Basel Badischer Bahnhof umsteigen in Tram Linie 8 bis Haltestelle „Weil am Rhein Bus Linie 55 bis Haltestelle „Vitra“ (Fahrtzeit ca. 15 Minuten) Bahnhof/Zentrum“, von dort zu Fuss der Beschilderung Vitra Vitra Campus oder mit der Deutschen Bahn nach Weil am Rhein (eine Campus entlang Müllheimer Str. folgen (Dauer ca. 15 Minuten, Charles-Eames-Str. 2 Haltestelle, Fahrzeit ca. 5 Minuten), von dort zu Fuss der Entfernung ca. 1 km) D-79576 Weil am Rhein Beschilderung Vitra Campus entlang Müllheimer Str. folgen +49 (0)7621 702 3500 (Dauer ca. 15 Minuten, Entfernung ca. 1 km) [email protected] Mit dem PKW www.vitra.com/campus von Bahnhof Basel SBB, Barfüsserplatz, Claraplatz, Kleinhüningen aus Deutschland Mo-So 10-18 Uhr Tram Linie 8 bis Haltestelle „Weil am Rhein Bahnhof/Zentrum“, Autobahn A5 Karlsruhe-Basel, Ausfahrt 69 Weil am Rhein, links 24. Dezember 10-14 Uhr von dort zu Fuss der Beschilderung Vitra Campus entlang abbiegen, Beschilderung Vitra Design Museum folgen Müllheimer Str. -

The Avant-Garde Architecture of Three 21St Century Universal Art Museums

ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS by Leslie Elaine Reid APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Richard Brettell, Chair ___________________________________________ Nils Roemer ___________________________________________ Maximilian Schich ___________________________________________ Charissa N. Terranova Copyright 2019 Leslie Elaine Reid All Rights Reserved ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS by LESLIE ELAINE REID, MLA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES - AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank, in particular, two people in Paris for their kindness and generosity in granting me interviews, providing electronic links to their work, and emailing me data on the Louvre-Lens for my dissertation. Adrién Gardère of studio adrien gardère and Catherine Mosbach of mosbach paysagists gave hours of their time and provided invaluable insight for this dissertation. And – even after I had returned to the United States, they continued to email documents that I would need. March 2019 iv ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS Leslie Elaine Reid, PhD The University of Texas at Dallas, 2019 ABSTRACT Supervising Professor: Richard Brettell Rooted in the late 18th and 19th century idea of the museum as a “library of past civilizations,” the universal or encyclopedic museum attempts to cover as much of the history of mankind through “art” as possible. -

Frank Gehry Biography

G A G O S I A N Frank Gehry Biography Born in 1929 in Toronto, Canada. Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Education: 1954 B.A., University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. 1956 M.A., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Select Solo Exhibitions: 2021 Spinning Tales. Gagosian, Beverly Hills, CA. 2016 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Building in Paris. Espace Louis Vuitton Venezia, Venice, Italy. 2015 Architect Frank Gehry: “I Have an Idea.” 21_21 Design Sight, Tokyo, Japan. 2015 Frank Gehry. LACMA, Los Angeles, CA. 2014 Frank Gehry. Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. Voyage of Creation. Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Athens, Greece. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. 2013 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. Frank Gehry At Work. Leslie Feely Fine Art. New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Paris Project Space, Paris, France. Frank Gehry at Gemini: New Sculpture & Prints, with a Survey of Past Projects. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. 2011 Frank Gehry: Outside The Box. Artistree, Hong Kong, China. 2010 Frank O. Gehry since 1997. Vitra Design Museum, Rhein, Germany. Frank Gehry: Eleven New Prints. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. 2008 Frank Gehry: Process Models and Drawings. Leslie Feely Fine Art, New York, NY. 2006 Frank Gehry: Art + Architecture. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. 2003 Frank Gehry, Architect: Designs for Museums. Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, MN. Traveled to Corcoran Art Gallery, Washington, D.C. 2001 Frank Gehry, Architect. -

박물관의 비정형 건축형태와 중심공간과의 상관성에 관한 연구 a Study on Correlation Between Atypical Architecture Classification and Main Public Space of the Museums

https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2021.21.03.088 박물관의 비정형 건축형태와 중심공간과의 상관성에 관한 연구 A Study on Correlation between Atypical Architecture Classification and Main Public Space of the Museums 박상준 신라대학교 실내건축디자인전공 Sang-Jun Park([email protected]) 요약 본 연구는 박물관 건축의 작품 중 특별 전시의 기능을 제외한 상설전시가 주를 이루는 박물관을 중심으로 하였다. 사례연구를 통해 나타난 정형, 비정형, 세그먼트, 사선형의 형태를 기준으로 하여, 164건의 작품사례 에 적용한 결과 건축형태를 비정형, 정형, 반정형, 세그먼트, 사선형, 선형으로 재분류 하고, 박물관 건축 형태 와 중심 공간과의 상관성의 유무를 유추함으로써 비정형 건축형태와 중심공간과의 관계가 성립하는가를 도출 하고자 다음과 같이 내용을 정리하였다. 전체적으로 대부분 비정형박물관건축형태와 일치하는 중심공간의 비 정형 형태로서 92.7% 분포도를 나타났다. 결과적으로 전반적으로 박물관 비정형 건축형태가 다수 나타났으며 정형보다는 비정형 건축형태에 있어서 중심공간과의 상관성이 성립되는 것으로서 향후 박물관 건축형태는 비 정형이 지속적으로 발전 할 것으로 추정되고 중심 공간 실내건축 설계는 건축형태와의 상관성을 고려하여 설 계를 지향하는 기초적 근거자료로서 제시하고자 한다. ■ 중심어 :∣박물관∣비정형∣건축형태∣상관성∣중심 공간∣ Abstract This study focused on the museums mainly holding permanent exhibitions except for the function of special exhibition in museum architectural works. This study aimed to draw the possibility to establish the relation between architectural form and central space of museums, by applying the forms like formal form, informal form, segment form, and diagonal form shown through a case study to total 164 work cases, reclassifying the architectural form into informal form, formal form, semi-formal form, segment form, diagonal form, and linear form, and then analogizing the matter of correlation between architectural form and central space of museums. -

Cocktails and Conversations Dialogues on Architectural Design

COCKTAILS AND CONVERSATIONS DIALOGUES ON ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN 6.21.18 TOM KUNDIG FAIA + ERIC OWEN MOSS FAIA IN CONVERSATION WITH JAMES S. RUSSELL FAIA ABBY SUCKLE FAIA COCKTAILS AND CONVERSATIONS DIALOGUES ON ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN TIDBITS FROM THE BOOK COMING JULY 2018 TO PURCHASE THE BOOK: AIA NY WELCOME DESK OR HTTPS://BIT.LY/2MKOEZF CURATED BY ABBY SUCKLE & WILLIAM SINGER 1 2 About Cocktails and Conversations The world may view architects’ idealism and aspiration as idiosyncratic, hopelessly romantic, if not naïve. Architects are constantly One Friday night about six years ago, we found ourselves standing in the Center for Architecture’s Tafel Hall browbeaten for daring to dream oversized dreams. Why this slavish devotion to Design and aspiration, the skeptic asks, when mean, sipping white wine from a plastic tumbler. We had just walked over from a late afternoon meeting at the Rubin cost-driven functionalism is all that’s being asked for. Architects don’t have too many venues to discuss what makes architecture meaningful, how to “practice” in a world determined to bury aspiration under mandates, and me-tooism. That’s the genius of Cocktails Museum of Art where we sat in the atrium while the museum transformed itself into a party venue. Tables were and Conversations and the Center for Architecture in New York. moved, bartenders began setting out glasses, and the space began to fill up. We remarked that it was amazing that every cultural institution of significance in New York City seemed to have a fun Friday evening Audiences are happily liberated from such over-serious formats as academic lectures. -

Deconstructivism: Richness Or Chaos to Postmodern Architecture Olivier Clement Gatwaza1, Xin CAO1

Deconstructivism: Richness or Chaos to Postmodern Architecture Olivier Clement Gatwaza1, Xin CAO1 1School of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Forestry University, 35 Qinghua East Road Beijing, 100083 China Abstract: In this paper, we examine the involvement of deconstructivism in the evolvement of postmodern architecture and ascertain its public acceptance dimensions as it progressively conquers postmodern architecture. To achieve this, we used internet search engines such as Google, Yahoo, Wikipedia and Web of Science, we also used knowledge repositories such as Google Scholar and the world’s largest travel site TripAdvisor to gather information and data about origin, evolution, characteristics and relationship between postmodernism and deconstructivism. We’ve based our judgment on concepts from famous architects, political leaders and public opinion to access the suitability of architectural style. The result of this research shows that postmodernism architecture buildings have an average 96.8% of visitor’s satisfaction ranking; while deconstructivism architecture buildings when taken alone, a decrease of 2% in visitor’s satisfaction ranking is perceived. In addition, strong comments against the upcoming architectural style confirm that deconstructivism still has ingredients to endorse in order to impose its trajectory towards the top of modern architecture. Being a piece of a globalized world, deconstructivism architecture in the most of the cases tends to disregard the history and culture of its location which compromise its innovative, -

Night Fever Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today 17 March – 9 September 2018

Vitra Design Museum Charles-Eames-Straße 2 79576 Weil am Rhein/Basel Germany www.design-museum.de PRESS CONFERENCE 15 March 2018, 2 pm OPENING 16 MARCH 2018, 6 pm Opening Talk with Ben Kelly, Peter Saville, and Konstantin Grcic PRESS DOWNLOADS www.design-museum.de/press_images Night Fever Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today 17 March – 9 September 2018 The nightclub is one of the most important design spaces in contemporary culture. Since the 1960s, nightclubs have been epicentres of pop culture, distinct spaces of nocturnal leisure providing architects and designers all over the world with opportunities and inspiration. »Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960 – Today« offers the first large-scale examination of the relationship between club culture and design, from past to present. The exhibition presents nightclubs as spaces that merge architecture and interior design with sound, light, fashion, graphics, and visual effects to create a modern Gesamtkunstwerk. Examples range from Italian clubs of the 1960s created by the protagonists of Radical Design to the legendary Studio 54 where Andy Warhol was a regular, from the Haçienda in Manchester designed by Ben Kelly to more recent concepts by the OMA architecture studio for the Ministry of Sound in London. The exhibits on display range from films and vintage photographs to posters, flyers, and fashion, but also include contemporary works by photographers and artists such as Mark Leckey, Chen Wei, and Musa N. Nxumalo. A spatial installation with music and light effects takes visitors on a fascinating journey through a world of glamour and subcultures – always in search of the night that never ends. -

The Emergence of the Glass Age of Museum Architecture from the 1990S

Redesigning the Physical Boundary: The Emergence of the Glass Age of Museum Architecture from the 1990s 潘 夢斐* Mengfei PAN 1.INTRODUCTION Contemporary museum architecture is buildings’ exalted status. This kind of seeing an age of glass. Both renovation extensive glazing has become an almost projects and new constructions have been indispensable part of the new generation of exploiting glass extensively, as if it is the museum architecture. best solution to serve the spatial functions, By contextualizing the phenomenon of present the architects’ concepts, and address extensive glazing in museum architecture, the institutions’ missions and social this paper aims to discern its connections expectations. Prominent examples include with the museum situation and the the Louvre Pyramid by I. M. Pei (1989) contemporaneity and locality of Japan. It and SANAA’s designs for The 21st Century argues that the increasing exploitation of Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa glass in museum architecture demonstrates (2004) and Louvre-Lens, France (2012). the influence of Neoliberalism on the public This trend of increasing use of glass by institutions and the architects to embrace museum architecture deviates from the visually appealing, technologically demanding, previous model of museums, temples and and commercial elements. It challenges the shrines, with grand staircases and formidable pre-dominant association of glass with look. A new physical boundary of museums, transparency and modernity and argues for a glass walls with their possibility to mediate contextualized reading of glass. Previous visual penetration and similarity with media research in the field of architectural studies interfaces that interact with the surrounding focused on glass employment in all types of and the spectators, is designed in contrast buildings and overlooked the specific with the older type that stresses the situation of museums; while museum studies * Ph. -

2.1. Royal Ontario Museum

The Icing on the Cake: Large-Scale Museum Extensions to Historic Buildings AR 597: Dissertation Kent School of Architecture University of Kent March 2015 IOANNIS MEXIS Supervisors: Dr. Manolo Guerci, Dr Timothy Brittain- Catlin. Word Count: 8789 ACKNOWLEGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Manolo Guerci and Dr. Timothy Brittain- Catlin for the valuable assistance in writing this essay. ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates how historic buildings are conserved and revitalized by extension projects. More specifically, it is about large scale contemporary museum extensions to historic compositions. The investigation of the topic is achieved through a series of case studies based on three different types of extension projects: “Juxtaposing free- standing extensions”, “Weaving extensions” and “Homogenous free-standing extensions”. Through the first category we will investigate: the Royal Ontario Museum by Daniel Libeskind (2007), MAXXI Museum by Zaha Hadid (2010) and Stedelijk Museum by Benthem Crouwel Architects (2012). All three of these extensions, are examples of bold interventions that contrasts both the historic building and their context and have become landmarks in the cities they are located in. In the second category, we will examine: the Neues Museum by David Chipperfield (2009) and Tate Modern by Herzog and de Meuron (2000). Both extensions are in direct relation with the existing building. The architects’ interventions are respectful towards the existing composites, giving the existing building a refreshed appearance. In the last category we will explore: the second extension project to Tate Modern by Herzog and de Meuron (2016) and the James Simon Gallery by David Chipperfield (2017). Both of these free standing extensions are cases of interventions that respect the existing building and their context but still manage to stand out of their context on a deferential manner. -

Alum Named Reader's Digest Editor Ballerina Captures Spotligh T At

Wednesday, March 20, 1996 • Vol. XXVII No. 108 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Matthews offers Alum named Reader's Digest editor By GWENDOLYN NORGLE The magazine, which has more than magazine. military view Associate News Edi10r 100 million readers monthly, contains And although Willcox was un stories selected from international, re available for comment on what influ A member of Notre Dame's class of gional and local sources. These sto ence his Notre Damr. education has on peacekeeping 1968, Christopher ries range from hard-hitting reports had on his career, his wife, Emily, Willcox. 49. has from the forefront of medicine, envi said "it helped a lot." Willcox went to By EMILY DIXON been named editor ronment and human rights to popular Austria through Notre Dame during Nt•w., Wri1er in-chief of "Header's features filled with humor and drama. his sophomore year, and the trip Digest," the world's The magazine has a wide variety of "opened so many doors" for him, she .John Btmson Matthews, a Notre Damn grad most widely read articles with universal appeal for peo said. It was "really helpful" in uatt~ and an assodate dean at the Marine magazine. ple of all ages and cultures. Willcox's acquisition of a job working Corps Command and Staff College at Quantico, As the sixth edi Willcox's career in journalism spans for Hadio Free Europe!Hadio Liberty Virg. discussed issues surrounding the United tor-in-chief in the. a 27 -year period. Executive editor of in Munich, Germany for four years, States Marines' in 74-year history of Willcox "Header's Digest" since June of 1994, according to his wife.