Joe Orton's 'Until She Screams,' Oh! Calcutta! and the Permisive 1960S Saunders, Graham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Queer Aes- Thetic Is Suggested in the Nostalgia of Orton’S List of 1930S Singers, Many of Whom Were Sex- Ual Nonconformists

Orton in Deckchair in Tangier. Courtesy: Orton Collection at the University of Leicester, MS237/5/44 © Orton Estate Rebel playwright Joe Orton was part of a ‘cool customer’, Orton shopped for the landscape of the Swinging Sixties. clothes on Carnaby Street, wore ‘hipster Irreverent black comedies that satirised pants’ and looked – in his own words the Establishment, such as Entertaining – ‘way out’. Although he cast himself Mr Sloane (1964), Loot (1965) and as an iconoclast, Emma Parker suggests What the Butler Saw (first performed that Orton’s record collection reveals a in 1969), contributed to a new different side to the ruffian playwright counterculture. Orton’s representation who furiously pitched himself against of same-sex desire on stage, and polite society. The music that Orton candid account of queer life before listened to in private suggests the same decriminalisation in his posthumously queer ear, or homosexual sensibility, that published diaries, also made him a shaped his plays. Yet, stylistically, this gay icon. Part of the zeitgeist, he was music contradicts his cool public persona photographed with Twiggy, smoked and reputation for riotous dissent. marijuana with Paul McCartney and wrote a screenplay for The Beatles. Described by biographer John Lahr as A Q U E E R EAR Joe Orton and Music 44 Music was important to Joe Orton from an early age. His unpublished teenage diary, kept Issue 37 — Spring 2017 sporadically between 1949 and 1951, shows that he saved desperately for records in the face of poverty. He also lovingly designed and constructed a record cabinet out of wood from his gran’s old dresser. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Audience Enrichment Guide

KEY ART: EXTENDED BACKGROUND Girl From the North Country | Study Guide Part One 1 Is created by cropping the layered extended background file. FILE NAME: GFTNC_EXT_COLORADJUST_ LAYERS_8.7.19_V3 ARTS EDUCATION AND ACTIVATION CREATED IN COLLABORATION WITH TDF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT 4 Girl From the North Country | Study Guide Part One 2 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This guide is intentionally designed to be a flexible teaching tool for teachers and facilitators focusing on different aspects of Girl From The North Country, with the option to further explore and activate knowledge. The guide is broken up into three sections: I. Getting to know the show, Conor McPherson story II. The Great Depression and historical context III. Bob Dylan and his music Activations are meant to take students from the realm of knowing a thing or fact into the realm of thinking and feeling. Activations can be very sophisticated, or simple, depending on the depth of exploration teachers and facilitators want to do with their students, or the age group they are working with. Girl From the North Country | Study Guide Part One 3 CONOR MCPHERSON ON BEING INSPIRED BY BOB DYLAN’S MUSIC ELYSA GARDNER for Broadwaydirect.com OCTOBER 1, 2019 For the celebrated Irish playwright Conor songs up; by setting it in the ‘30s, we could McPherson, Girl From the North Country rep- do them another way. I knew I wanted a lot of resents a number of firsts: his first musical, his vocals and a lot of choral harmonies.” first work set in the United States, and, oh yes, A guitarist himself, McPherson had always his first project commissioned by Bob Dylan been interested in Dylan’s music, but he — the first theater piece ever commissioned admits, “I was not one of those people who by the iconic Nobel Prize–winning singer/ could cover every decade of his career. -

Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 3-24-2016 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Barry, Todd, "From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1041. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1041 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 This dissertation examines how theatre and law have worked together to produce and regulate gay male lives since the 1895 Oscar Wilde trials. I use the term “gay legal theatre” to label an interdisciplinary body of texts and performances that include legal trials and theatrical productions. Since the Wilde trials, gay legal theatre has entrenched conceptions of gay men in transatlantic culture and influenced the laws governing gay lives and same-sex activity. I explore crucial moments in the history of this unique genre: the Wilde trials; the British theatrical productions performed on the cusp of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act; mainstream gay American theatre in the period preceding the Stonewall Riots and during the AIDS crisis; and finally, the contemporary same-sex marriage debate and the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). The study shows that gay drama has always been in part a legal drama, and legal trials involving gay and lesbian lives have often been infused with crucial theatrical elements in order to legitimize legal gains for LGBT people. -

The Byrds' Mcguinn at Joe College by Kent Hoover Rock in That Era

OUTSIDE WEATHER Temperatures in the 70s Baseball team loses to for Joe College Weekend, The Chronicle li ttle chance of rain today. Duke University Volume 72, Number 135 Friday, April 15,1977 Durham, North Carolina Search reopened for Trinity dean By George Strong to his discipline," Turner observed. The University is again searching for a "There is a real sense in which a staff replacement for David Clayborne, the as position is a detour for someone who is sistant dean of Trinity College who re getting started." signed last summer. In late March, Wright informed John George Wright, the history graduate Fein, dean of Trinity College, of Ken student hired several months ago to be an tucky's offer. "I felt obliged — though assistant dean beginning this fall, has ac regretful — to release him from his ob cepted a faculty position at the University ligation to Duke," Fein said. of Kentucky, his alma mater. "I don't know whether I expected this or His decision leaves Trinity College once not," commented Richard Wells, associate again without a black academic dean. dean of Trinity College. 1 thought maybe Wright maintained that neither qualms it would work out But good people are about the Duke administration nor finan always in demand" cial considerations had entered his de Wells is heading up the screening com cision. mittee for applicants to the vacated posi Couldn't refuse tion. Fein and Gerald Wison, coordinator 1 knew I would eventually move into for the dean's staff, join Wells on the com "What kind of kids eat Armour hot dogs?" Harris Asbeil, Joe College chef, my academic field," he said, "and once the mittee. -

Joe Orton: the Oscar Wilde of the Welfare State

JOE ORTON: THE OSCAR WILDE OF THE WELFARE STATE by KAREN JANICE LEVINSON B.A. (Honours), University College, London, 1972 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of English) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1977 (c) Karen Janice Levinson, 1977 ii In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 30 April 1977 ABSTRACT This thesis has a dual purpose: firstly, to create an awareness and appreciation of Joe Orton's plays; moreover to establish Orton as a focal point in modern English drama, as a playwright whose work greatly influenced and aided in the definition of a form of drama which came to be known as Black Comedy. Orton's flamboyant life, and the equally startling method of his death, distracted critical attention from his plays for a long time. In the last few years there has been a revival of interest in Orton; but most critics have only noted his linguistic ingenuity, his accurate ear for the humour inherent in the language of everyday life which led Ronald Bryden to dub him "the Oscar Wilde of Welfare State gentility." This thesis demonstrates Orton's treatment of social matters: he is concerned with the plight of the individual in society; he satirises various elements of modern life, particularly those institutions which wield authority (like the Church and the Police), and thus control men. -

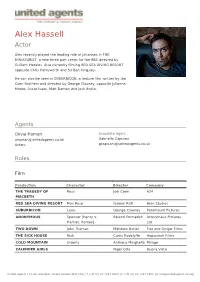

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

John Bull University of Lincoln 'We Cannot All Be Masters, Nor All Masters/Cannot Truly Be Follow'd': Joe Orton's Holida

John Bull University of Lincoln ‘We cannot all be masters, nor all masters/Cannot truly be follow’d’: Joe Orton’s Holiday Camp Bacchae – matters of class, genre and medium in The Erpingham Camp. Joe Orton is thought of largely as a writer for the theatre, and yet three of his plays first appeared on television: as many as first appeared on stage. In what follows I want to consider just one of these, The Erpingham Camp (1967) and, by looking at the way in which it evolved both before and after its first outing on television, to offer to both reposition this play in the oeuvre and to re-open the debate about what Orton was moving towards theatrically.1 Before considering its development, it will be useful first to reflect on the public perception of the young dramatist at the time he started to work on it. From a distance of some fifty years, and in a very different social and cultural climate, it is extremely hard to fully comprehend the kind of impact that Joe Orton’s plays had when first produced: and, concomitantly, it is just about impossible to understand the degree of hostility that they aroused in many quarters, and yet it is important to do so in order to understand how Orton dealt practically with the implications of this hostility. Nor was it confined to sections of the paying public and to newspaper critics, as reaction to the work that caused the greatest furore at the time, Loot (1964), will demonstrate. Examination of the Lord Chamberlain’s archive reveals that there was considerable internal pressure to refuse to grant it a licence at all: a reader’s report by Kyle Fletcher (8 December 1964) argued that the play 1 Work on this article has been greatly aided by research in the following archives: ‘Joe Orton Collection’, University of Leicester; ‘’Lord Chancellor’s Papers’ and ‘Peter Gill Archive’, British Library; ‘Lyndsay Anderson Archive’, University of Stirling; the British Film Institute archive. -

Timeline: Royal Court International (1989–2013) Compiled by Elaine Aston and Elyse Dodgson

Timeline: Royal Court International (1989–2013) Compiled by Elaine Aston and Elyse Dodgson The Timeline charts the Royal Court’s London-based presentations of international plays and related events from 1989–2013. It also records the years in which fi rst research trips overseas were made and exchanges begun. Writers are listed alphabetically within recorded events; translators for the Court are named throughout; directors are listed for full productions and major events. Full productions are marked with an asterisk (*) – other play listings are staged readings. 1989: First international Summer School hosted by the Royal Court 1992: Court inaugurates exchange with Germany 1993: Summer School gains support from the British Council Austrian & German Play Readings (plays selected and commissioned by the Goethe-Institut; presented in October) Rabenthal Jorg Graser; Soliman Ludwig Fels; In den Augen eines Fremdung Wolfgang Maria Bauer; Tatowierung Dea Loher; A Liebs Kind Harald Kislinger; Alpenglühen Peter Turrini 1994: First UK writers exchange at the Baracke, Deutsches Theater, Berlin, coordinated by Michael Eberth. British writers were Martin Crimp, David Greig, Kevin Elyot, Meredith Oakes and David Spencer. Elyse Dodgson, Stephen Daldry and Robin Hooper took part in panel discussions 1995: Daldry and Dodgson make initial contacts in Palestine Plays from a Changing Country – Germany (3–6 October) Sugar Dollies Klaus Chatten, trans. Anthony Vivis; The Table Laid Anna Langhoff, trans. David Spencer; Stranger’s House Dea Loher, trans. David Tushingham; Waiting Room Germany Klaus Pohl, trans. David Tushingham; Jennifer Klemm or Comfort and Misery of the Last Germans D. Rust, trans. Rosee Riggs Waiting Room Germany Klaus Pohl, Downstairs, director Mary Peate, 1 to 18 November* 1996: Founding of the International Department by Daldry; Dodgson appointed Head. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

Still on the Road 1990 Us Fall Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 1990 US FALL TOUR OCTOBER 11 Brookville, New York Tilles Center, C.W. Post College 12 Springfield, Massachusetts Paramount Performing Arts Center 13 West Point, New York Eisenhower Hall Theater 15 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 16 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 17 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 18 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 19 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 21 Richmond, Virginia Richmond Mosque 22 Pittsburg, Pennsylvania Syria Mosque 23 Charleston, West Virginia Municipal Auditorium 25 Oxford, Mississippi Ted Smith Coliseum, University of Mississippi 26 Tuscaloosa, Alabama Coleman Coliseum 27 Nashville, Tennessee Memorial Hall, Vanderbilt University 28 Athens, Georgia Coliseum, University of Georgia 30 Boone, North Carolina Appalachian State College, Varsity Gymnasium 31 Charlotte, North Carolina Ovens Auditorium NOVEMBER 2 Lexington, Kentucky Memorial Coliseum 3 Carbondale, Illinois SIU Arena 4 St. Louis, Missouri Fox Theater 6 DeKalb, Illinois Chick Evans Fieldhouse, University of Northern Illinois 8 Iowa City, Iowa Carver-Hawkeye Auditorium 9 Chicago, Illinois Fox Theater 10 Milwaukee, Wisconsin Riverside Theater 12 East Lansing, Michigan Wharton Center, University of Michigan 13 Dayton, Ohio University of Dayton Arena 14 Normal, Illinois Brayden Auditorium 16 Columbus, Ohio Palace Theater 17 Cleveland, Ohio Music Hall 18 Detroit, Michigan The Fox Theater Bob Dylan 1990: US Fall Tour 11530 Rose And Gilbert Tilles Performing Arts Center C.W. Post College, Long Island University Brookville, New York 11 October 1990 1. Marines' Hymn (Jacques Offenbach) 2. Masters Of War 3. Tomorrow Is A Long Time 4. -

South Coast Repertory Is a Professional Resident Theatre Founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson

IN BRIEF FOUNDING South Coast Repertory is a professional resident theatre founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson. VISION Creating the finest theatre in America. LEADERSHIP SCR is led by Artistic Director David Ivers and Managing Director Paula Tomei. Its 33-member Board of Trustees is made up of community leaders from business, civic and arts backgrounds. In addition, hundreds of volunteers assist the theatre in reaching its goals, and about 2,000 individuals and businesses contribute each year to SCR’s annual and endowment funds. MISSION South Coast Repertory was founded in the belief that theatre is an art form with a unique power to illuminate the human experience. We commit ourselves to exploring urgent human and social issues of our time, and to merging literature, design, and performance in ways that test the bounds of theatre’s artistic possibilities. We undertake to advance the art of theatre in the service of our community, and aim to extend that service through educational, intercultural, and community engagement programs that harmonize with our artistic mission. FACILITY/ The David Emmes/Martin Benson Theatre Center is a three-theatre complex. Prior to the pandemic, there were six SEASON annual productions on the 507-seat Segerstrom Stage, four on the 336-seat Julianne Argyros Stage, with numerous workshops and theatre conservatory performances held in the 94-seat Nicholas Studio. In addition, the three-play family series, “Theatre for Young Audiences,” produced on the Julianne Argyros Stage. The 20-21 season includes two virtual offerings and a new outdoors initiative, OUTSIDE SCR, which will feature two productions in rotating rep at the Mission San Juan Capistrano in July 2021.