Dissertationsummary the Linguistic Relationships Between Greek and the Anatolian Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20Th Century and Beyond

The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20th Century and Beyond The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jasanoff, Jay. 2017. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20th Century and Beyond. In Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics, edited by Jared Klein, Brian Joseph, and Matthias Fritz, 31-53. Munich: Walter de Gruyter. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41291502 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 18. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian ■■■ 35 18. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the Twentieth Century and Beyond 1. Two epoch-making discoveries 4. Syntactic impact 2. Phonological impact 5. Implications for subgrouping 3. Morphological impact 6. References 1. Two epoch-making discoveries The ink was scarcely dry on the last volume of Brugmann’s Grundriß (1916, 2nd ed., Vol. 2, pt. 3), so to speak, when an unexpected discovery in a peripheral area of Assyriol- ogy portended the end of the scholarly consensus that Brugmann had done so much to create. Hrozný, whose Sprache der Hethiter appeared in 1917, was not primarily an Indo-Europeanist, but, like any trained philologist of the time, he could see that the cuneiform language he had deciphered, with such features as an animate nom. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — the LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D. Joseph, The Ohio State University 0. Introduction A stunning result of linguistic research in the 19th century was the recognition that some languages show correspondences of form that cannot be due to chance convergences, to borrowing among the languages involved, or to universal characteristics of human language, and that such correspondences therefore can only be the result of the languages in question having sprung from a common source language in the past. Such languages are said to be “related” (more specifically, “genetically related”, though “genetic” here does not have any connection to the term referring to a biological genetic relationship) and to belong to a “language family”. It can therefore be convenient to model such linguistic genetic relationships via a “family tree”, showing the genealogy of the languages claimed to be related. For example, in the model below, all the languages B through I in the tree are related as members of the same family; if they were not related, they would not all descend from the same original language A. In such a schema, A is the “proto-language”, the starting point for the family, and B, C, and D are “offspring” (often referred to as “daughter languages”); B, C, and D are thus “siblings” (often referred to as “sister languages”), and each represents a separate “branch” of the family tree. B and C, in turn, are starting points for other offspring languages, E, F, and G, and H and I, respectively. Thus B stands in the same relationship to E, F, and G as A does to B, C, and D. -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g. -

Central Anatolian Languages and Language Communities in the Colony Period : a Luwian-Hattian Symbiosis and the Independent Hittites*

1333-08_Dercksen_07crc 05-06-2008 14:52 Pagina 137 CENTRAL ANATOLIAN LANGUAGES AND LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES IN THE COLONY PERIOD : A LUWIAN-HATTIAN SYMBIOSIS AND THE INDEPENDENT HITTITES* Petra M. Goedegebuure (Chicago) 1. Introduction and preliminary remarks This paper is the result of the seemingly innocent question “Would you like to say something on the languages and peoples of Anatolia during the Old Assyrian Period”. Seemingly innocent, because to gain some insight on the early second millennium Central Anatolian population groups and their languages, we ideally would need to discuss the relationship of language with the complex notion of ethnicity.1 Ethnicity is a subjective construction which can only be detected with certainty if the ethnic group has left information behind on their sense of group identity, or if there is some kind of ascription by others. With only the Assyrian merchant documents at hand with their near complete lack of references to the indigenous peoples or ethnic groups and languages of Anatolia, the question of whom the Assyrians encountered is difficult to answer. The correlation between language and ethnicity, though important, is not necessarily a strong one: different ethnic groups may share the same language, or a single ethnic group may be multilingual. Even if we have information on the languages spoken in a certain area, we clearly run into serious difficulties if we try to reconstruct ethnicity solely based on language, the more so in proto-historical times such as the early second millennium BCE in Anatolia. To avoid these difficulties I will only refer to population groups as language communities, without any initial claims about the ethnicity of these communities. -

Indo-European Languages and Branches

Indo-European languages and branches Language Relations One of the first hurdles anyone encounters in studying a foreign language is learning a new vocabulary. Faced with a list of words in a foreign language, we instinctively scan it to see how many of the words may be like those of our own language.We can provide a practical example by surveying a list of very common words in English and their equivalents in Dutch, Czech, and Spanish. A glance at the table suggests that some words are more similar to their English counterparts than others and that for an English speaker the easiest or at least most similar vocabulary will certainly be that of Dutch. The similarities here are so great that with the exception of the words for ‘dog’ (Dutch hond which compares easily with English ‘hound’) and ‘pig’ (where Dutch zwijn is the equivalent of English ‘swine’), there would be a nearly irresistible temptation for an English speaker to see Dutch as a bizarrely misspelled variety of English (a Dutch reader will no doubt choose to reverse the insult). When our myopic English speaker turns to the list of Czech words, he discovers to his pleasant surprise that he knows more Czech than he thought. The Czech words bratr, sestra,and syn are near hits of their English equivalents. Finally, he might be struck at how different the vocabulary of Spanish is (except for madre) although a few useful correspondences could be devised from the list, e.g. English pork and Spanish puerco. The exercise that we have just performed must have occurred millions of times in European history as people encountered their neighbours’ languages. -

Transfer of Morphemes and Grammatical Structure in Ancient Anatolia

CHAPTER FIFTEEN TRANSFER OF MORPHEMES AND GRAMMATICAL STRUCTURE IN ANCIENT ANATOLIA Folke Josephson Recent research has successfully developed historical sociolinguistics in the study of Anatolian and has stressed the importance of Hittite-Luvian bilingualism. Case endings and nominal suffixes were brought into Hit- tite in Luvian loan words. Adoption of Hurrian morphemes by IE Anato- lian was insignificant in spite of intensive Hurrian—Luvian bilingualism. Structural traits that have been believed to be of Hattic and Hurrian ori- gin and developmental tendencies leading to unusual syntactic traits of Indo-European Anatolian should be seen as developments of inherited Indo-European structures. Anatolian split ergativity can be explained internally. The historical development of the functional scope of local/ directional enclitic particles is also an internal phenomenon. Later com- mon trends in the historical development of Anatolian like the loss of several sentence introductory connective particles and local/directional particles imply a reversal of common trends that led to the establishment of earlier functions of these elements. Structural dissimilarities account for the lack of transfer of morphemes and grammatical elements from Hurrian and Hattic, but Hattic may have been influenced by IE Anatolian structures. 1 Introduction In an article on ancient Anatolia as a linguistic area and areal diffusion as a challenge to the comparative method (Watkins 2001), Calvert Watkins was concerned with diffusional convergence in phonology and morpho- syntax and emphasized that the Anatolian subgroup of Indo-European had close contacts with Hattic and the Hurrian of Mitanni and ancient contacts with Semitic Sumero-Akkadian. On the subject of three syntactic isoglosses of Indo-European Anatolian, i.e. -

As William Makepeace Thackeray (1811–63) Would Have Said

CONCLUSIONS Everything has its end, so does this book. “Our play is played out,” as William Makepeace Thackeray (1811–63) would have said. Our peculiar journey in space and time to the sources of Indo-European cultures and languages is also over. It is left only to draw important conclusions. The world of Indo-European cultures and languages is really huge, diverse, and marvelous. The history of the ancient Indo-Europeans and the peoples with whom they communicated in prehistory in many aspects is still shrouded in mystery. We know for sure that the Indo-Europeans were not autochthones neither in Europe nor in India. Although the word Europe is originally a prominent concept of Greek civilisation, basically used in a large number of modern languages, its etymology (as well as that of Asia) is of unknown ultimate provenance, which also speaks in favour of the later appearance of the Indo-Europeans on this continent. We also know that other civilisations flourished before them, but the origins of these civilisations or the specific circumstances of the invasion of Indo-Europeans tribes there – all this is the subject of much speculation impossible to verify. According to the Kurgan hypothesis that seems the most likely, the tribes who spoke Proto-Indo-European dialects originally occupied the territory that stretched between the Pontic steppe (the region of modern southern Russia and eastern Ukraine) and the Ural Mountains, and between the upper reaches of the Volga and the foothills of the Caucasus. Approximately during the 5th and 4th millennia BC, they split into various parts and began their movements in three main directions: to the east into Central Asia and later farther, to the south through the Caucasus into Asia Minor, and to the west into Europe. -

Europaio: a Brief Grammar of the European Language Reconstruct Than the Individual Groupings

1. Introduction 1.1. The Indo-European 1. The Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred languages and dialects, including most of the major languages of Europe, as well as many in South Asia. Contemporary languages in this family include English, German, French, Spanish, Countries with IE languages majority in orange. In Portuguese, Hindustani (i.e., mainly yellow, countries in which have official status. [© gfdl] Hindi and Urdu) and Russian. It is the largest family of languages in the world today, being spoken by approximately half the world's population as their mother tongue, while most of the other half speak at least one of them. 2. The classification of modern IE dialects into languages and dialects is controversial, as it depends on many factors, such as the pure linguistic ones (most of the times being the least important of them), the social, economic, political and historical ones. However, there are certain common ancestors, some of them old, well-attested languages (or language systems), as Classic Latin for Romance languages (such as French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Rumanian or Catalan), Classic Sanskrit for the Indo-Aryan languages or Classic Greek for present-day Greek. Furthermore, there are other, still older -some of them well known- dialects from which these old language systems were derived and later systematized, which are, following the above examples, Archaic Latin, Archaic Sanskrit and Archaic Greek, also attested in older compositions and inscriptions. And there are, finally, old related dialects which help develop a Proto-Language, as the Faliscan (and Osco-Umbrian for many scholars) for Latino-Faliscan (Italic for many), the Avestan for Indo-Iranian or the Mycenaean for Proto-Greek. -

Ancient Anatolian Languages and Cultures in Contact: Some Methodological Observations1

Paola Cotticelli-Kurras†, Federico Giusfredi‡ † (University of Verona, Italy; [email protected]) ‡ (University of Verona, Italy; [email protected]) Ancient Anatolian languages and cultures in contact: some methodological observations1 In this paper, we will review the methodological and theoretical frameworks that have been developed to deal with the study of language contact and linguistic areas. We have tried to apply these methods to ancient contexts to check the existence of conditions for identifying language areas. Finally, we will provide examples of the combined linguistic and cultural-historical approach to ancient contact areas for phenomena in reciprocal direction, with particular ref- erence to the case of the Aegean and Ancient Near Eastern context of Ancient Anatolia. Keywords: Anatolian languages, language contact, cuneiform, cultural contact, linguistic areas. 1. Language contact, linguistic area and other related concepts In the last years, several scholars have discussed the contact between Ancient Anatolian lan- guages and some neighboring ones, including Greek and a number of Ancient Near Eastern ones, as indicative of a “linguistic area”, due to the fact that more general cultural contact be- tween language groups is a sign of the presence of linguistic areas. In order to successfully as- sess these approaches, it is appropriate to take into consideration the linguistic framework of reference. In the 1920s, Trubetzkoy (1928) 2 proposed the expression Sprachbund, “language league”, to describe the fact that unrelated languages could converge at the level of their structures fol- lowing intense contact. He took as example the almost prototypical area of the Balkans. The concept of Sprachbund has been coined to underline the evidence that languages can share similarities even though they are not genetically related. -

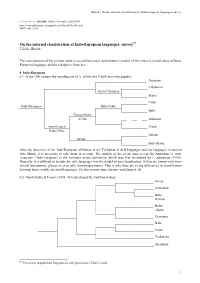

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3. -

Proto-Indo-Europeans: the Prologue

Proto-Indo-Europeans: The Prologue Alexander Kozintsev Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Saint-Petersburg and Saint-Petersburg State University, Russia This study collates linguistic, genetic, and archaeological data relevant to the problem of the IE homeland and proto-IE (PIE) migrations. The idea of a proto-Anatolian (PA) migration from the steppe to Anatolia via the Balkans is refuted by linguistic, archaeological, and genetic facts, whereas the alternative scenario, postulating the Indo-Uralic homeland in the area east of the Caspian Sea, is the most plausible. The divergence between proto-Uralians and PIEs is mirrored by the cultural dichotomy between Kelteminar and the early farming societies in southern Turkmenia and northern Iran. From their first homeland the early PIEs moved to their second homeland in the Near East, where early PIE split into PA and late PIE. Three migration routes from the Near East to the steppe across the Caucasus can be tentatively reconstructed — two early (Khvalynsk and Darkveti-Meshoko), and one later (Maykop). The early eastern route (Khvalynsk), supported mostly by genetic data, may have been taken by Indo-Hittites. The western and the central routes (Darkveti-Meshoko and Maykop), while agreeing with archaeological and linguistic evidence, suggest that late PIE could have been adopted by the steppe people without biological admixture. After that, the steppe became the third and last PIE homeland, from whence all filial IE dialects except Anatolian spread in various directions, one of them being to the Balkans and eventually to Anatolia and the southern Caucasus, thus closing the circle of counterclockwise IE migrations around the Black Sea.