Excavating Recognition for the Capcom Sound Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greenstreet Publisher 3

2002 - 2005 Issues 1 to 10 ZXF10: 53 LOOKING FOR UNIQUE? ZXF merchandise: treat yourself to a piece worked a lot better had it been of 21st Century ZX Spectrum memorabilia... full cover) - a homage of sorts to the artwork of John Harris (who designed the cover to the original Spectrum manual, introduction booklet and Interface 1 & Micro- The ZX Spectrum on Your PC drive manual). Issue 6's cover "well-written and superbly presented" - took me ages and was inspired by Micro Mart Oliver Frey's CRASH issue 36 cover. Downloaded over 2,000 times and featured on Issue 7's cover was a detail from a the Retro Gamer cover disk, this guide to photo of my own Spectrum soft- Spectrum emulation on the PC is the perfect ware collection (passed through a introduction for ex-Spectrum users returning to whole cocktail of PSP fiters). Issue their first ever computer. Written by ZXF editor 8 - a popular cover, apparently - Colin Woodcock, The ZX Spectrum on Your is testament to what you can do PC teaches you how to use modern PC with a digital camera and a sand emulators to play all those old favourites, as pit on a bright Sunday morning well as some of the more advanced features (sorry to those of you who imagin- on offer too. You've read the electronic ed me digging away on a beach version, now enjoy the luxury of a profession- somewhere, but the ZXF expense ally printed paperback! account wouldn't stump up the bus fare). Issue nine was straight- 78 page paperback $11.99 (about £6.60) forward - a Christmassy 3D stero- gram featuring Horace (I'd always thought that Spectrum sprites might lend themselves particularly well to stereograms and wanted ZXF Mug to experiment). -

Acquiring Literacy: Techne, Video Games and Composition Pedagogy

ACQUIRING LITERACY: TECHNE, VIDEO GAMES AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY James Robert Schirmer A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2008 Committee: Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Lynda D. Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Richard C. Gebhardt Gary Heba © 2008 James R. Schirmer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Recent work within composition studies calls for an expansion of the idea of composition itself, an increasing advocacy of approaches that allow and encourage students to greater exploration and more “play.” Such advocacy comes coupled with an acknowledgement of technology as an increasingly influential factor in the lives of students. But without a more thorough understanding of technology and how it is manifest in society, any technological incorporation is almost certain to fail. As technology advances along with society, it is of great importance that we not only keep up but, in fact, reflect on process and progress, much as we encourage students to do in composition courses. This document represents an exercise in such reflection, recognizing past and present understandings of the relationship between technology and society. I thus survey past perspectives on the relationship between techne, phronesis, praxis and ethos with an eye toward how such associative states might evolve. Placing these ideas within the context of video games, I seek applicable explanation of how techne functions in a current, popular technology. In essence, it is an analysis of video games as a techno-pedagogical manifestation of techne. With techne as historical foundation and video games as current literacy practice, both serve to improve approaches to teaching composition. -

1300 Games in 1 Games List

1300 Games in 1 Games List 1. 1942 – (Shooting) [609] 2. 1941 : COUNTER ATTACK – (Shooting) [608] 3. 1943 : THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – (Shooting) [610] 4. 1943 KAI : MIDWAY KAISEN – (Shooting) [611] 5. 1944 : THE LOOP MASTER – (Shooting) [521] 6. 1945KIII – (Shooting) [604] 7. 19XX : THE WAR AGAINST DESTINY – (Shooting) [612] 8. 2020 SUPER BASEBALL – (Sport) [839] 9. 3 COUNT BOUT – (Fighting) [70] 10. 4 EN RAYA – (Puzzle) [1061] 11. 4 FUN IN 1 – (Shooting) [714] 12. 4-D WARRIORS – (Shooting) [575] 13. STREET : A DETECTIVE STORY – (Action) [303] 14. 88GAMES – (Sport) [881] 15. 9 BALL SHOOTOUT – (Sport) [850] 16. 99 : THE LAST WAR – (Shooting) [813] 17. D. 2083 – (Shooting) [768] 18. ACROBAT MISSION – (Shooting) [678] 19. ACROBATIC DOG-FIGHT – (Shooting) [735] 20. ACT-FANCER CYBERNETICK HYPER WEAPON – (Action) [320] 21. ACTION HOLLYWOOOD – (Action) [283] 22. AERO FIGHTERS – (Shooting) [673] 23. AERO FIGHTERS 2 – (Shooting) [556] 24. AERO FIGHTERS 3 – (Shooting) [557] 25. AGGRESSORS OF DARK KOMBAT – (Fighting) [64] 26. AGRESS – (Puzzle) [1054] 27. AIR ATTACK – (Shooting) [669] 28. AIR BUSTER : TROUBLE SPECIALTY RAID UNIT – (Shooting) [537] 29. AIR DUEL – (Shooting) [686] 30. AIR GALLET – (Shooting) [613] 31. AIRWOLF – (Shooting) [541] 32. AKKANBEDER – (Shooting) [814c] 33. ALEX KIDD : THE LOST STARS – (Puzzle) [1248] 34. ALIBABA AND 40 THIEVES – (Puzzle) [1149] 35. ALIEN CHALLENGE – (Fighting) [87] 36. ALIEN SECTOR – (Shooting) [718] 37. ALIEN STORM – (Action) [322] 38. ALIEN SYNDROME – (Action) [374] 39. ALIEN VS. PREDATOR – (Action) [251] 40. ALIENS – (Action) [373] 41. ALLIGATOR HUNT – (Action) [278] 42. ALPHA MISSION II – (Shooting) [563] 43. ALPINE SKI – (Sport) [918] 44. AMBUSH – (Shooting) [709] 45. -

Gabriel Flamm +46 736 987 582 [email protected]

Gabriel Flamm +46 736 987 582 [email protected] “My objective is to make sure you feel the intended emotion in every moment” May 2012 – present • Battlefiled V, EA Dice Cinematic Animator Took scenes from mockup in animation software to functional and ready for render farm in Frostbite Polished and finalized several scenes – characters, props, vehicles. • Star Wars Battlefront II, Lucasfilm, EA Dice Cinematics Heroes vs Villains – Intro My responsibility was to come up with ideas for intro moves and direct mocap actors Animate the cameras and set up the logic Galactic Assault - Intros & Outros I created all intros when it comes to character and vehicle animations timed to the systematic camera. I did also set up the cameras, unique for each team on all levels. The outros are real time events where I animated cameras, characters, vehicles and some of the existing VFX assets. Emotes I came up with all Emotes - both VO and motion, planned and directed motion capture I gave direction to a VO actor, to be used as a reference for all other VO actors I created briefs, material and demand lists for outsourcing as well as being part of the feedback process with the animation director • Battlefield 1, EA Dice Cinematic Animator Took scenes from mockup in animation software to functional and ready for render farm in Frostbite Polished and finalized several scenes Animated airplanes in Friends in high places Animated cameras, characters and objects in Nothing is written real time cinematic, timed to VO Added background characters where needed Implemented and polished a few in-game 1p and 3p animations. -

The 1-Bit Instrument: the Fundamentals of 1-Bit Synthesis

BLAKE TROISE The 1-Bit Instrument The Fundamentals of 1-Bit Synthesis, Their Implementational Implications, and Instrumental Possibilities ABSTRACT The 1-bit sonic environment (perhaps most famously musically employed on the ZX Spectrum) is defined by extreme limitation. Yet, belying these restrictions, there is a surprisingly expressive instrumental versatility. This article explores the theory behind the primary, idiosyncratically 1-bit techniques available to the composer-programmer, those that are essential when designing “instruments” in 1-bit environments. These techniques include pulse width modulation for timbral manipulation and means of generating virtual polyph- ony in software, such as the pin pulse and pulse interleaving techniques. These methodologies are considered in respect to their compositional implications and instrumental applications. KEYWORDS chiptune, 1-bit, one-bit, ZX Spectrum, pulse pin method, pulse interleaving, timbre, polyphony, history 2020 18 May on guest by http://online.ucpress.edu/jsmg/article-pdf/1/1/44/378624/jsmg_1_1_44.pdf from Downloaded INTRODUCTION As unquestionably evident from the chipmusic scene, it is an understatement to say that there is a lot one can do with simple square waves. One-bit music, generally considered a subdivision of chipmusic,1 takes this one step further: it is the music of a single square wave. The only operation possible in a -bit environment is the variation of amplitude over time, where amplitude is quantized to two states: high or low, on or off. As such, it may seem in- tuitively impossible to achieve traditionally simple musical operations such as polyphony and dynamic control within a -bit environment. Despite these restrictions, the unique tech- niques and auditory tricks of contemporary -bit practice exploit the limits of human per- ception. -

Specifika Praxe Zvukového Designu Počítačových Her V Českém Prostředí

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV HUDEBNÍ VĚDY TEORIE INTERAKTIVNÍCH MÉDIÍ Bc. Roman Zigo Specifika praxe zvukového designu počítačových her v českém prostředí Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Martin Flašar, Ph.D. 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem magisterskou diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně s použitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. ................................................. Poděkování Velmi rád bych zde poděkoval za pomoc, vstřícnost, trpělivost a užitečné rady PhDr. Martinu Flašarovi, Ph.D., za užitečné kontakty Mgr. Jaroslavu Kolářovi, všem spolupracujícím sound designérům, jmenovitě Františku Fukovi, Filipu Oščádalovi, Tomáši Šlápotovi a Tomáši Dvořákovi za ochotu a čas, který mi věnovali. Dále bych rád vyjádřil úctu ke své rodině, která mi nepřestala být důležitým zázemím ani během mého prodlužovaného studia. Na závěr děkuji Mgr. Bohdaně Kalinové, za její nekončící podporu a pochopení nejen během psané této magisterské diplomové práce. Obsah 1. Úvod..........................................................................................5 2. Teoretická část...........................................................................7 2.1. Historie tvorby zvuků počítačových her.............................7 2.2. Situace v českém prostředí v 80. letech............................11 2.2.1. František Fuka............................................................13 2.2.2. Filip Oščádal – začátky..............................................17 2.3. Filip Oščádal a 90. léta v českém prostředí......................19 -

Somnus from Final Fantasy Xv by Yoko Shimomura Sheet Music

Somnus From Final Fantasy Xv By Yoko Shimomura Sheet Music Download somnus from final fantasy xv by yoko shimomura sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of somnus from final fantasy xv by yoko shimomura sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 17960 times and last read at 2021-09-24 05:50:55. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of somnus from final fantasy xv by yoko shimomura you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Percussion Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ Read Sheet Music ] Other Sheet Music Eyes On Me From Final Fantasy Viii Eyes On Me From Final Fantasy Viii sheet music has been read 11947 times. Eyes on me from final fantasy viii arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 04:50:14. [ Read More ] Aerith Theme Final Fantasy Vii Aerith Theme Final Fantasy Vii sheet music has been read 28761 times. Aerith theme final fantasy vii arrangement is for Beginning level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 16:39:34. [ Read More ] Tifa Theme Final Fantasy Vii Nobuo Uematsu Tifa Theme Final Fantasy Vii Nobuo Uematsu sheet music has been read 24953 times. Tifa theme final fantasy vii nobuo uematsu arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 02:54:11. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

Instruction Booklet

CAPCOM ENTERTAINMENT, INC., 800 Concar Drive, Suite 300, San Mateo, CA 94402 © CAPCOM CO., LTD. 2006, 2008 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Wii development by Ready At Dawn Studios LLC. CAPCOM and the CAPCOM LOGO are registered trademarks of CAPCOM CO., LTD. ŌKAMI is a trademark of CAPCOM CO., LTD. The typefaces included herein are solely developed by DynaComware. The rating icon is a registered trademark of the Entertainment Software Association. All other trademarks are owned by their respective owners. www.capcom.com/okami PRINTED IN USA INSTRUCTION BOOKLET ESRB on Front: 14 x 21 mm OKAMI: Wii Manual Cover - Round 5 Prepared by Eclipse Advertising on: February 28, 2008 PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT The Official Seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. Dolby, Pro Logic, and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. Manufactured under license from Dolby Laboratories. WARNING – Seizures This game is presented in Dolby Pro Logic II. To play games that carry the Dolby Pro Logic II logo in surround sound, you will need a Dolby Pro Logic II, Dolby Pro Logic or Dolby Pro Logic IIx receiver. These • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or receivers are sold separately. -

4. the Street Fighter Lady

4. The Street Fighter Lady Invisibility and Gender in Game Composition Andy Lemon and Hillegonda C Rietveld Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association December 2019, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 107-133. ISSN 2328-9422 © The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — NonCommercial –NonDerivative 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/ 2.5/). IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights ABSTRACT The international success of Japanese game design provides an example of the invisibility of female game composers, as well as of gendered identification in game music production and sound design. Yoko Shimomura, the female composer who produced the iconic soundtrack for the 1991 arcade game, Street Fighter II (Capcom 1991), seems to have been invisible to game developers and music producers, which is partly due to the way in which the game is credited as a team effort. Regardless of their personal gender identity, game composers respond to themed briefs by 107 108 The Street Fighter Lady drawing on transnational musical ideas and gendered stereotypes that resonate with the Global Popular. Game music, as imagined as suitable for hyper-masculine game arcades, seems to draw on a masculinist aesthetic developed in Hollywood compositions. In turn, Street Fighter II’s music and the competitive game culture of arcade fighting games has been interwoven with masculinist music scenes of hip-hop and grime. The discussion of the music of Street Fighter II and the musical versions it inspired, nevertheless highlights that although seemingly simplified gendered stereotypes are reproduced within the game, gender identification itself can be complex within the context of game music composition. -

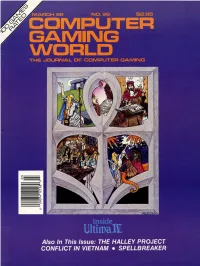

Computer Gaming World Issue 26

Number 26 March 1986 FEATURES Conflict In Viet Nam 14 The View From a Playtester M. Evan Brooks Inside Ultima IV 18 Interview with Lord British The Halley Project 24 Tooling Through the Solar System Gregg Williams Silent Service 28 Designer's Notes Sid Meier Star Trek: The Kobayashi Alternative 36 A Review Scorpia DEPARTMENTS Taking A Peek 6 Screen Photos and Brief Comments Scorpion's Tale 12 Playing Tips on SPELLBREAKER Scorpia Strategically Speaking 22 Game Playing Tips Atari Playfield 30 Koronis Rift and The Eidolon Gregg Williams Amiga Preferences 32 A New Column on the Amiga Roy Wagner Commodore Key 38 Flexidraw, Lode Runner's Rescue, and Little Computer People Roy Wagner The Learning Game 40 Story Tree Bob Proctor Over There 41! A New Column on British Games Leslie B. Bunder Reader Input Device 43 Game Ratings 48 100 Games Rated Accolade is rewarded with an excellent Artworx 20863 Stevens Creek Blvd graphics sequence. Joystick. 150 North Main Street Cupertino, CA 95014 One player. C-64, IBM. ($29.95 Fairport, NY 14450 408-446-5757 & $39.95). Circle Reader Service #4 800-828-6573 FIGHT NIGHT: Arcade style Activision FP II: With Falcon Patrol 2 the boxing game. A choice of six 2350 Bayshore Frontage Road player controls a fighter plane different contenders to battle Mountain View, CA 94043 equipped with the latest mis- for the heavyweight crown. The 800-227-9759 siles to combat the enemy's he- player has the option of using licopter-attack squadrons. Fea- the supplied boxers or creating HACKER: An adventure game tures 3-D graphics, sound ef- his own challenger. -

BIONIC COMMANDO “CHAIN of COMMAND” by Andy Diggle

BIONIC COMMANDO “CHAIN OF COMMAND” by Andy Diggle www.andydiggle.com PAGE 1 Hey Colin, welcome to the party! These first few pages are fairly exposition-heavy, so please do let me know if I haven’t left you enough room for the dialogue. But don’t worry, the blab-level should drop once we start blowin’ shit up real good... It’s not a hard-and-fast rule, but where possible it would be cool if you could try to favor full-width panels; this’ll make it easier to slice it up into a web-friendly format. As always, if you have any questions or concerns, don’t hesitate to drop me a line and I can re-work the script where necessary. Have fun! 1) A twin-rotor MILITARY TRANSPORT VTOL thunders dramatically towards us through gunmetal skies. Circa 2035 A.D. tech level. CAPTION I don’t look out the window any more. It hurts too much. CAPTION All that sky. All that freedom. 2) BIG! Reverse angle; the VTOL descends towards the TASC BIONICS DIVISION HQ - a heavily-fortified bunker-like complex with the TASC logo (the tesselated hexagons on the BC game logo) emblazoned on the side. Heavy blast doors yawn open to reveal a deep, cylindrical landing shaft atop the structure, like the mouth of a squat concrete volcano. Most of the complex lies deep underground, and all we’re seeing here is the tip of the iceberg. CAPTION This metal box is my whole world now. CAPTION But since I lost everything..