'Working Through Change: an Insider's Analysis of FE Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Letter to Address Systemic Racism in Further Education

BLACK FURTHER EDUCATION LEADERSHIP GROUP 5th August 2020 Open letter to address systemic racism in further education Open letter to: Rt. Hon. Boris Johnson, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Gavin Williamson MP, Secretary of State for Education, funders of further education colleges; regulatory bodies & further education membership bodies. We, the undersigned, are a group of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) senior leaders, and allies, who work or have an interest in the UK further education (FE) sector. The recent #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) global protest following the brutal murder of George Floyd compels us all to revisit how we address the pervasive racism that continues to taint and damage our society. The openness, solidarity and resolve stirred by #BLM is unprecedented and starkly exposes the lack of progress made in race equality since ‘The Stephen Lawrence Enquiry’. Against a background of raised concerns about neglect in healthcare, impunity of policing, cruelty of immigration systems – and in education, the erasure of history, it is only right for us to assess how we are performing in FE. Only by doing so, can we collectively address the barriers that our students, staff and communities face. The personal, economic and social costs of racial inequality are just too great to ignore. At a time of elevated advocacy for FE, failure to recognise the insidious nature of racism undermines the sector’s ability to fully engage with all its constituent communities. The supporting data and our lived experiences present an uncomfortable truth, that too many BAME students and staff have for far too long encountered a hostile environment and a system that places a ‘knee on our neck’. -

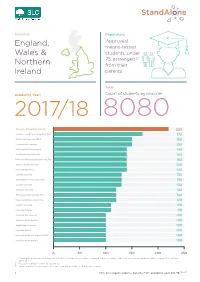

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019/20

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019/20 Roehampton University Company Registration Number 5161359 (England and Wales) Contents Chair of Council’s Welcome ..................................................................................... 4 Strategic Report ........................................................................................................... 6 Key Performance Indicators.................................................................................. 8 Financial Review ....................................................................................................10 Student Experience ...............................................................................................12 Staff Experience.....................................................................................................15 Learning, Teaching and Student Success ........................................................16 Research .................................................................................................................18 Outreach, Participation and Community Engagement .................................. 20 Responsible University .........................................................................................22 Risk and Uncertainty .............................................................................................24 Members of Council Report ...................................................................................26 Statement of Public Benefit.................................................................................28 -

NEWSLETTER Summer 2020

ANNUAL ROUND-UP NEWSLETTER Summer 2020 ANNUAL ART EXHIBITION Page 23 STUDENTS EMBRACE ONLINE LEARNING Page 20 Designed by Desislava Doneva CoulsdonCOULSDON College student COLLEGE FE FOODBANK FRIDAY CHRISTMAS PANTO Page 24 Page 07 APPRENTICESHIPS AT CROYDON COLLEGE Page 10 IT STUDENTS VISIT OASIS ACADEMY RYELANDS A group of Croydon College Level 3 Information Lecturer Christopher Hunt, said ‘The exercise Technology students visited Oasis Academy was very useful. We collected more than 100 Ryelands on Wednesday 4 March to work with reviews within an hour alone. Full credit goes a group of primary school children to test out to Kian Riley who not only collected the most mobile Apps that they had developed in class. reviews, but also gained the highest average TRIPS rating for his App.’ The App they presented to the school children was intended to help young children perform Samantha Francis, Assistant Principal and Head arithmetic with whole numbers between 1 and of Maths at Oasis Academy Ryelands was very 02 12. The brief of the App was to ensure it had pleased with the visit. She appreciated the calm & VISITS colour, music and other sounds that would approach of the students and the presence of appeal to young children. young male role models – who are not often seen in the Primary School environment. BTEC TRAVEL AND TOURISM CROYDON COLLEGE WARMLY CULINARY STUDENTS TRIP TO BRIGHTON WELCOMED THE DSM FOUNDATION GRANTED WORK PLACEMENTS On Thursday 12th March 2020, The Daniel Spargo- Back in February 2020, our Culinary Mabbs Foundation attended Croydon College for the students received the fantastic news 300th performance of the play ‘I Love You, Mum – that they would be given work placements I Promise I Won’t Die’ performed by Wizard Theatre at various Corbin and King restaurants for Level 3 ESOL students. -

6Th Form and College Open Days 2020.21 PDF File

6th Form and College OPEN DAYS 2020/21 • PLEASE CONFIRM DETAILS WITH THE 6th FORM OR COLLEGE BEFORE ATTENDING (and register if required) • PLEASE ATTEND WITH A PARENT, CARER OR RESPONSIBLE ADULT Access Creative College Virtual Meet and Greet, Open Days and Taster Days: 0800 28 18 42 www.accesscreative.ac.uk Book time slot online: www.accesscreative.ac.uk/open-events/ (Specialist Courses: Event Production, Film/Video & Photography, Games Art/Technology, Graphic Digital Open Day: 27 October 2020 Design, Music Performance/Production, Studio + Live Sound, Vocal Artist) Archbishop Tenison’s CE High School October 2020, details to be confirmed; for details, email 0208 688 4014 www.archten.croydon.sch.uk [email protected] Ark Globe Academy Virtual Open Event planned; for further details check 0207 407 6877 www.arkglobe.org webpage: www.arkglobe.org/sixth-form/how-apply Ark Walworth Academy Will be an online event. 0207 450 9570 www.walworthacademy.org Check website at start of October for details Ashcroft Technology Academy Open Mornings, to be confirmed: check sixth form page 0208 877 0357 Open Forum for International Baccalaureate: www.atacademy.org.uk To express your interest, email [email protected] Attlee A Level Academy (New City College) Register online for virtual open day, details to be 0207 510 7510 confirmed: www.ncclondon.ac.uk/a-level-academy www.ncclondon.ac.uk/open Bacon’s College Register interest for Sixth Form admissions and Open 0207 237 1928 www.baconscollege.co.uk Events: www.baconscollege.co.uk/sixth-form/apply/ -

Progression of College Students in London to Higher Education 2011 - 2014

PROGRESSION OF COLLEGE STUDENTS IN LONDON TO HIGHER EDUCATION 2011 - 2014 Sharon Smith, Hugh Joslin and Jill Jameson Prepared for Linking London by the HIVE-PED Research Team, Centre for Leadership and Enterprise in the Faculty of Education and Health at the University of Greenwich Authors: Sharon Smith, Hugh Joslin and Professor Jill Jameson Centre for Leadership and Enterprise, Faculty of Education and Health University of Greenwich The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Linking London, its member organisations or its sponsors. Linking London Birkbeck, University of London BMA House Tavistock Square London WC1H 9JP http://www.linkinglondon.ac.uk January 2017 Linking London Partners – Birkbeck, University of London; Brunel University, London; GSM London; Goldsmiths, University of London; King’s College London; Kingston University, London; London South Bank University; Middlesex University; Ravensbourne; Royal Central School for Speech and Drama; School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London; University College London; University of East London; University of Greenwich; University of Westminster; Barnet and Southgate College; Barking and Dagenham College; City and Islington College; City of Westminster College; The College of Enfield, Haringey and North East London; Harrow College; Haringey Sixth Form College; Havering College of Further and Higher Education; Hillcroft College; Kensington and Chelsea College; Lambeth College; Lewisham Southwark College; London South East Colleges; Morley College; Newham College of Further Education; Newham Sixth Form College; Quintin Kynaston; Sir George Monoux College; Uxbridge College; Waltham Forest College; Westminster Kingsway College; City and Guilds; London Councils Young People’s Education and Skills Board; Open College Network London; Pearson Education Ltd; TUC Unionlearn 2 Foreword It gives me great pleasure to introduce this report to you on the progression of college students in London to higher education for the years 2011 - 2014. -

Revitalising the Retail Core

TECHNICAL APPENDIX FURTHER EVIDENCE AND JUSTIFICATION Croydon Town Centre Opportunity Area Planning Framework (OAPF) Adopted 2013 Table of Contents Section Page i. Table of contents 2 1. Development capacity modelling 3 2. Housing mix 24 3. Affordable housing 26 4. Commercial floorspace 29 5. Retail 42 6. Modernism in the COA 52 7. Public realm – Connected Croydon 73 8. Cherished spaces in the COA 77 9. Meanwhile uses 80 10. Building typologies 84 11. Transport and parking 95 2 1. Development capacity component Policy PPS 3 states “Local Planning Authorities should set out in Local Development Documents (LDD) their policies and strategies for delivering the level of housing provision, including identifying broad locations and specific sites that will enable continuous delivery of housing for 15 years from the date of adoption, taking into account the level of housing provision set out in [the London Plan]”2 (see paragraph 5 below). It says Local Planning Authorities “should consider the extent to which emerging LDDs… can have regard to the policies in this statement whilst maintaining plan making programmes”3. London Plan Policy 2.7 Outer London Economy talks about identifying and bringing forward capacity in and around town centres with good public transport accessibility to accommodate leisure, retail and civic needs and higher density housing, Policy 2.13 Opportunity Areas and Intensification Areas requires OA’s such as the CMC to contribute towards meeting (or where appropriate, exceeding) the minimum guidelines for housing and/or indicative estimates for employment capacity set out as tested through opportunity area planning frameworks. Policy 2.16 on Strategic Outer London Development Centres also identifies Croydon as a strategic office location, with a strong existing market and the capacity to expand this offer. -

Information and Advice for Young People

Information and Advice back to contents for Young People welcome 2018 2019 getting started moving forward apprenticeships, foundation, employment SEND advice Post-16 course Prospectus listings schools/ Your options after year 11 in Croydon colleges open event calendar 2 Contents back to contents Welcome ........................................ 3 Course Listings ................................ 31 Getting Started ................................ 5 • How to apply to Sixth Form and College • Why do I have to stay in learning • What type of course suits me? until I am 18 years old? • Vocational Course Listings • What if I can’t decide what I want to do? • AS and A Level Course Listings welcome • GCSE Course Listings Moving Forward .............................. 8 • Other Croydon Colleges and Sixth Forms • Map of Croydon Schools and Colleges • How can I prepare for my interview? (please find an interactive copy of the application • How can I get financial help and support form online at www.youngcroydon.org.uk) getting to help me stay on my course? • What if things don’t work out? – Useful links started and advice School and College Sixth • What type of learning environment suits me? Forms in Croydon ............................. 43 • Archbishop Tenison’s Apprenticeships, Foundation Church of England Sixth Form moving Learning and Employment ............. 13 • The BRIT School forward • Capel Manor College, • Work Based Learning – Apprenticeships Crystal Palace Park Centre • Work Based Learning – Traineeships • Coloma Convent Girls’ School -

2021 Virtual Open Events

2021 Virtual Open Events 7 January 4.30 – 6.30pm 11 March 4.30 – 6.30pm 30 June 4.30 – 6.30pm HE Taster Week 10 – 13 May To find out more visit croydonuniversitycentre.ac.uk Croydon University Centre An outstanding centre of teaching, a collegiate community of extraordinary people, a unique setting – a university In partnership with the University of centre like no other. Roehampton 1/3 87% of our students of students agree achieve a 1st or 2.1 that timetables are degree outcome flexible and work with their busy lives Graduate data 2019/20 92% of degree students said their course challenged them to achieve their best work Top 10 Our degree courses are validated by one of London’s top 10 universities Contents Degree Courses 06 We are very proud of our long history of delivering higher Why Choose Croydon? education courses right here in the heart of Croydon. Why choose Croydon University? 06 Business & Management 16 Hear why our We are passionate about offering high quality, affordable Top reasons to study with us Criminology, Psychology & students choose the university degree and higher national courses directly to 18 Social Justice University Centre our community and those from further afield. Why choose Croydon? 08 Early Childhood Studies Higher Education can be life changing. Studying a higher Discover Croydon 20 education course at our bespoke university centre will not Public Health & Social Care 22 only allow you to gain a qualification, it will give you the Adult Nursing opportunity to change your life by opening up career University of Roehampton 24 opportunities and broadening your horizons. -

237 Colleges in England.Pdf (PDF,196.15

This is a list of the formal names of the Corporations which operate as colleges in England, as at 3 February 2021 Some Corporations might be referred to colloquially under an abbreviated form of the below College Type Region LEA Abingdon and Witney College GFEC SE Oxfordshire Activate Learning GFEC SE Oxfordshire / Bracknell Forest / Surrey Ada, National College for Digital Skills GFEC GL Aquinas College SFC NW Stockport Askham Bryan College AHC YH York Barking and Dagenham College GFEC GL Barking and Dagenham Barnet and Southgate College GFEC GL Barnet / Enfield Barnsley College GFEC YH Barnsley Barton Peveril College SFC SE Hampshire Basingstoke College of Technology GFEC SE Hampshire Bath College GFEC SW Bath and North East Somerset Berkshire College of Agriculture AHC SE Windsor and Maidenhead Bexhill College SFC SE East Sussex Birmingham Metropolitan College GFEC WM Birmingham Bishop Auckland College GFEC NE Durham Bishop Burton College AHC YH East Riding of Yorkshire Blackburn College GFEC NW Blackburn with Darwen Blackpool and The Fylde College GFEC NW Blackpool Blackpool Sixth Form College SFC NW Blackpool Bolton College FE NW Bolton Bolton Sixth Form College SFC NW Bolton Boston College GFEC EM Lincolnshire Bournemouth & Poole College GFEC SW Poole Bradford College GFEC YH Bradford Bridgwater and Taunton College GFEC SW Somerset Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College SFC SE Brighton and Hove Brockenhurst College GFEC SE Hampshire Brooklands College GFEC SE Surrey Buckinghamshire College Group GFEC SE Buckinghamshire Burnley College GFEC NW Lancashire Burton and South Derbyshire College GFEC WM Staffordshire Bury College GFEC NW Bury Calderdale College GFEC YH Calderdale Cambridge Regional College GFEC E Cambridgeshire Capel Manor College AHC GL Enfield Capital City College Group (CCCG) GFEC GL Westminster / Islington / Haringey Cardinal Newman College SFC NW Lancashire Carmel College SFC NW St. -

Croydon College 2019-20 Access and Participation Plan

Croydon College 2019-20 Access and Participation Plan Page 1 of 20 CONTENTS CROYDON COLLEGE ............................................................................................................... 1 2019-20 ACCESS AND PARTICIPATION PLAN ....................................................................... 1 1. ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT PERFORMANCE .................................................... 3 2. AMBITIONS AND STRATEGY ................................................................................. 6 2.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 6 2.3 OUTREACH ACTIVITY ................................................................................................. 10 2.4 RAISING ATTAINMENT IN SCHOOLS ......................................................................... 11 2.5 COLLABORATIVE WORK ............................................................................................ 11 3. TARGETS ............................................................................................................... 12 3.1 TARGETS AND MILESTONES .......................................................................................... 12 4. ACCESS, STUDENT SUCCESS AND PROGRESSION MEASURES ................... 12 5. INVESTMENT ......................................................................................................... 14 5.1 BURSARIES AND HARDSHIP FUNDING ..................................................................... 15 5.2 APPROACH -

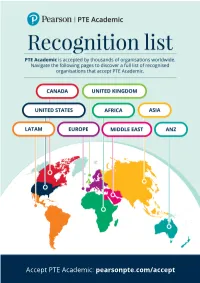

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource