Revitalising the Retail Core

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De'borah Passes the 1,2,3 Test

Imagine Croydon – we’re Who is the all-time Top tips to keep offering you the chance top Wembley scorer your home safe from to influence the way our at Selhurst Park? unwanted visitors borough develops Page 8 Page 12 Page 2 Issue 28 - April 2009 yourYour community newspaper from your councilcroydonwww.croydon.gov.uk Wandle Park lands £400,000 jackpot Residents’ vote brings cash bonanza to fund community improvements. The Friends of Wandle River Wandle – returning The £400,000 brings the Park are jumping for joy surface water to the total funding for the park to at having won £400,000 town for the first time £1.4m, adding to the £1m from the Mayor of London in 40 years and bringing funding secured from the to give their favourite open social and environmental Barratt Homes development space a radical makeover. benefits to the area. adjoining the park. And the money comes Restoration of the Mark Thomas, chairman thanks to the fantastic Wandle, a tributary of the Friends of Wandle response of residents to of the Thames, will Park, said: “It’s great to the call for them to vote see the forming of see that all the work that and help bring the much- an adjoining lake. we put into promoting needed funding to Croydon. Other enhancements the potential of our local Wandle Park gained planned for Wandle park has paid off. the second highest number Park include sprucing “We look forward to of votes in London, with up the skate park and working with the council 5,371 people supporting it. -

Building Blockbusters © Rory Walsh

Viewpoint Building blockbusters © Rory Walsh Time: 15 mins Region: Greater London Landscape: urban Location: Wellesley Road / George Street traffic island, Croydon CR0 1YD Grid reference: TQ 32559 65637 Keep an eye out for: The tallest building, the Saffron Tower, is coloured to look like a crocus plant - Croydon’s name comes from Old English for ‘crocus valley’ To many people, Croydon has a rather negative image. At first sight, this view along Wellesley Road could summarise common opinions that the area is a concrete wasteland. Rows of tower blocks loom above, while busy roads surround us on all sides. Traffic passes from the left, right, ahead, behind and even below us through an echoing underpass. Yet this scene is one of London’s most popular filming locations. Stars like Brad Pitt, Tom Hanks and Kevin Costner have trod Croydon’s ‘mean streets’. Even Batman has swooped by. How did unfashionable Croydon become a Hollywood hotspot? Lower Manhattan from Jersey City © King of Hearts, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-3.0 Take in the scene – does it remind you of anywhere else? In a certain light - and with some studio trickery – the tall buildings and wide roads could be mistaken for New York or Chicago. Besides fitting looks, Croydon has attractive costs. Filming in big cities can be expensive, disruptive and time-consuming. A film permit alone in Manhattan is $300 per day. Add crew wages and other costs over weeks of shooting and a film’s budget balloons. Croydon’s competitive fees combine with its ‘mini-Manhattan’ feel to create an ideal stand-in. -

Valuation Report

Valuation Report Colonnades Leisure Park, Purley Way Croydon Vegagest SGR SpA, Fondo Europa Immobiliare 1 July 2015 Colonnades Retail Park, Purley Way, Croydon July 2015 Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Basis of the Valuation ................................................................................................................. 2 3 General Principals .......................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Measurements and Areas .....................................................................................................................................................3 3.3 Titles .......................................................................................................................................................................................3 3.4 Town Planning and Other Statutory Regulations ...............................................................................................................4 3.5 Site Visit ..................................................................................................................................................................................4 3.6 Structural Survey ...................................................................................................................................................................4 3.7 Deleterious materials -

Open Letter to Address Systemic Racism in Further Education

BLACK FURTHER EDUCATION LEADERSHIP GROUP 5th August 2020 Open letter to address systemic racism in further education Open letter to: Rt. Hon. Boris Johnson, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Gavin Williamson MP, Secretary of State for Education, funders of further education colleges; regulatory bodies & further education membership bodies. We, the undersigned, are a group of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) senior leaders, and allies, who work or have an interest in the UK further education (FE) sector. The recent #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) global protest following the brutal murder of George Floyd compels us all to revisit how we address the pervasive racism that continues to taint and damage our society. The openness, solidarity and resolve stirred by #BLM is unprecedented and starkly exposes the lack of progress made in race equality since ‘The Stephen Lawrence Enquiry’. Against a background of raised concerns about neglect in healthcare, impunity of policing, cruelty of immigration systems – and in education, the erasure of history, it is only right for us to assess how we are performing in FE. Only by doing so, can we collectively address the barriers that our students, staff and communities face. The personal, economic and social costs of racial inequality are just too great to ignore. At a time of elevated advocacy for FE, failure to recognise the insidious nature of racism undermines the sector’s ability to fully engage with all its constituent communities. The supporting data and our lived experiences present an uncomfortable truth, that too many BAME students and staff have for far too long encountered a hostile environment and a system that places a ‘knee on our neck’. -

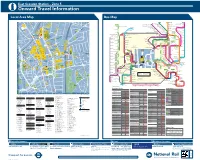

Local Area Map Bus Map

East Croydon Station – Zone 5 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map FREEMASONS 1 1 2 D PLACE Barrington Lodge 1 197 Lower Sydenham 2 194 119 367 LOWER ADDISCOMBE ROAD Nursing Home7 10 152 LENNARD ROAD A O N E Bell Green/Sainsbury’s N T C L O S 1 PA CHATFIELD ROAD 56 O 5 Peckham Bus Station Bromley North 54 Church of 17 2 BRI 35 DG Croydon R E the Nazarene ROW 2 1 410 Health Services PLACE Peckham Rye Lower Sydenham 2 43 LAMBERT’S Tramlink 3 D BROMLEY Bromley 33 90 Bell Green R O A St. Mary’s Catholic 6 Crystal Palace D A CRYSTAL Dulwich Library Town Hall Lidl High School O A L P H A R O A D Tramlink 4 R Parade MONTAGUE S S SYDENHAM ROAD O R 60 Wimbledon L 2 C Horniman Museum 51 46 Bromley O E D 64 Crystal Palace R O A W I N D N P 159 PALACE L SYDENHAM Scotts Lane South N R A C E WIMBLEDON U for National Sports Centre B 5 17 O D W Forest Hill Shortlands Grove TAVISTOCK ROAD ChCCheherherryerryrry Orchard Road D O A 3 Thornton Heath O St. Mary’s Maberley Road Sydenham R PARSON’S MEAD St. Mary’s RC 58 N W E L L E S L E Y LESLIE GROVE Catholic Church 69 High Street Sydenham Shortlands D interchange GROVE Newlands Park L Junior School LI E Harris City Academy 43 E LES 135 R I Croydon Kirkdale Bromley Road F 2 Montessori Dundonald Road 198 20 K O 7 Land Registry Office A Day Nursery Oakwood Avenue PLACE O 22 Sylvan Road 134 Lawrie Park Road A Trafalgar House Hayes Lane G R O V E Cantley Gardens D S Penge East Beckenham West Croydon 81 Thornton Heath JACKSON’ 131 PLACE L E S L I E O A D Methodist Church 1 D R Penge West W 120 K 13 St. -

BROCHURE at 100% 86 X 107Mm

CROYDON CROYDON IKON PURLEY WAY PLAYING FIELD CROYDON DUPPAS HILL CENTRALE SHOPPING CENTRE WANDLE PARK WEST CROYDON STATION FROM ART AND CULTURE TO FASHION AND DINING, CROYDON IS CHANGING TRANSFORMATION 2 IKON WADDON STATION VUE CINEMA VALLEY RETAIL PARK IKEA AMPERE WAY TRAM STATION 3 IKON AN EXCITING, CONTEMPORARY NEW DEVE L O PM E N T 4 IKON THE B R A V O THE ALPHA THE CHARLIE APARTMENTS APARTMENTS APARTMENTS THE D E L T A & THE E C H O APARTMENTS Croydon is riding the crest of a multi-billion pound regeneration wave, and with IKON within close proximity to the borough’s business, leisure and transport hotspots, you’ll be at the centre of it all. DEVELOPMENT LAYOUT IS INDICATIVE ONLY AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE. 5 IKON BIG INVESTMENT CREATES A BRAND NEW VISION Known as South London’s economic heartland, Croydon is undergoing a £5.25bn regeneration programme, making it the ideal time to snap up a new apartment at IKON. The town is already home to more than 13,000 places of work, which collectively employ a total of 141,000 people. Croydon has been dubbed the Silicon Valley of South London thanks to the proliferation of technology companies here, while other sectors include financial services and engineering. More than 20,000 further jobs are set to be created over the next few years, thanks to the redevelopment of the area which includes office accommodation, retail, restaurant and leisure space. Croydon’s redevelopment also includes major investment in its schools, with additional plans to partner with an international university to enhance its higher education presence. -

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017 Part of the London Plan evidence base COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Contents Chapter Page 0 Executive summary 1 to 7 1 Introduction 8 to 11 2 Large site assessment – methodology 12 to 52 3 Identifying large sites & the site assessment process 53 to 58 4 Results: large sites – phases one to five, 2017 to 2041 59 to 82 5 Results: large sites – phases two and three, 2019 to 2028 83 to 115 6 Small sites 116 to 145 7 Non self-contained accommodation 146 to 158 8 Crossrail 2 growth scenario 159 to 165 9 Conclusion 166 to 186 10 Appendix A – additional large site capacity information 187 to 197 11 Appendix B – additional housing stock and small sites 198 to 202 information 12 Appendix C - Mayoral development corporation capacity 203 to 205 assigned to boroughs 13 Planning approvals sites 206 to 231 14 Allocations sites 232 to 253 Executive summary 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Executive summary 0.1 The SHLAA shows that London has capacity for 649,350 homes during the 10 year period covered by the London Plan housing targets (from 2019/20 to 2028/29). This equates to an average annualised capacity of 64,935 homes a year. -

Whitgift CPO Inspector's Report

CPO Report to the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government by Paul Griffiths BSc(Hons) BArch IHBC an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Date: 13 July 2015 The Town and Country Planning Act 1990 The Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976 The Acquisition of Land Act 1981 The London Borough of Croydon (Whitgift Centre and Surrounding Land bounded by and including parts of Poplar Walk, Wellesley Road, George Street and North End) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 Inquiry opened on 3 February 2015 Accompanied Inspection was carried out on 3 February 2015 The London Borough of Croydon (Whitgift Centre and Surrounding Land bounded by and including parts of Poplar Walk, Wellesley Road, George Street and North End) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 File Ref: NPCU/CPO/L5240/73807 CPO Report NPCU/CPO/L5240/73807 File Ref: NPCU/CPO/L5240/73807 The London Borough of Croydon (Whitgift Centre and Surrounding Land bounded by and including parts of Poplar Walk, Wellesley Road, George Street and North End) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 The Compulsory Purchase Order was made under section 226(1)(a) and 226(3)(a) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, Section 13 of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976, and the Acquisition of Land Act 1981, by the London Borough of Croydon, on 15 April 2014. The purposes of the Order are (a) facilitating the carrying out of development, redevelopment or improvement on or in relation to the land comprising the demolition of existing -

(Public Pack)Supplement Agenda To

Public Document Pack General Purposes & Audit Committee Supplementary Agenda 4. Brick by Brick Audit Report (Pages 3 - 30) The draft Brick by Brick Director’s Report and Financial Statements 2018-19 are attached at Appendix 1. 5. Financial Performance Report (Pages 31 - 72) This report presents to the Committee progress on the delivery of the Council’s Financial Strategy. 6. Audit Findings Report (Pages 73 - 266) The reports include the Council’s management responses to the recommendations. 7. Annual Governance Statement (Pages 267 - 296) This report details the Annual Governance Statement (AGS), for 2018/19 at Appendix 1. JACQUELINE HARRIS BAKER Michelle Gerning Council Solicitor and Monitoring Officer 020 8726 6000 x84246 London Borough of Croydon [email protected] Bernard Weatherill House www.croydon.gov.uk/meetings 8 Mint Walk, Croydon CR0 1EA This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 4 REPORT TO: GENERAL PURPOSES & AUDIT COMMITTEE 23 JULY 2019 SUBJECT: AUDIT REPORT FOR BRICK BY BRICK CROYDON LTD 2018-19 ACCOUNTS LEAD OFFICER: JACQUELINE HARRIS-BAKER EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF RESOURCES CABINET MEMBER: COUNCILLOR ALISON BUTLER CABINET MEMBER FOR HOMES AND GATEWAY SERVICES AND DEPUTY LEADER (STATUTORY) COUNCILLOR SIMON HALL CABINET MEMBER FOR FINANCE AND RESOURCES WARDS: ALL CORPORATE PRIORITY/POLICY CONTEXT/AMBITIOUS FOR CROYDON: The preparation and publication of the Brick by Brick Croydon Ltd (BBB) final accounts provides assurance that the company’s overall financial position is sound. This underpins the delivery of the company’s business plan and the achievement of its key corporate objectives. Strong financial governance and stewardship ensures that the company’s resources are allocated in an effective and responsible way that enables it to deliver multi-tenure housing across the borough in a manner that is commercially efficient, and thereby maximizes the return to the company’s sole shareholder, the London Borough of Croydon. -

For Coloured Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf by Ntozake Shange

For Coloured Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf By Ntozake Shange Director: Adam Tulloch Adam has trained at The Brit School, Talawa Theatre Company and Theatre Royal Stratford East. His acting credits include; Windrush: The Next Generation (Stratford Circus), Squid (Lyric Hammersmith) The Black Battalions (The Yesterday Channel), # I am England (Lillian Baylis Studio). He also had guest appearances in The Bill, Holby Blue and Silent Witness. His writing and directing credits include; For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Isn’t Enuf (SOAS), Through the Wire (Old Red Lion Theatre), The Gun (Lyric Hammersmith) and AccePtance (Warehouse Theatre). Adam is recent Rare award winner and his next production Olaudah Equiano, the Enslaved African will tour this year’s Edinburgh Fringe Festival at the Space @ Jury’s Inn from 1st- 16th August. Movement Director: Sharon Henry Sharon trained at Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts and is a versatile dancer and actress. Her dancing credits include; Urban Dance Fusion, Street yiP- dance around eight motives, Darwin’s building Orchestra and Kannari. Her recent choreography credits include; Through the Wire (Old Red Lion Theatre) and For Colored Girls (SOAS). Sharon will also be working as a movement director on Olaudah Equiano, the Enslaved African. In her spare time, Sharon enjoys singing and teaching dance. Costume Design: Sian Edwards Sian trained at The Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts as a community arts practitioner. She has worked for a variety of Theatre Companies teaching Drama including; The Polka Theatre, The New Wimbledon Theatre and Dramabuds. Sian also designs and makes costumes. -

Playing Fields, Purley Way, Croydon, CR0 4RJ

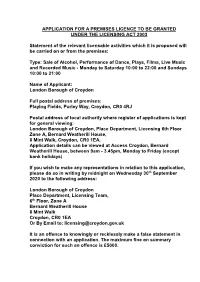

APPLICATION FOR A PREMISES LICENCE TO BE GRANTED UNDER THE LICENSING ACT 2003 Statement of the relevant licensable activities which it is proposed will be carried on or from the premises: Type: Sale of Alcohol, Performance of Dance, Plays, Films, Live Music and Recorded Music - Monday to Saturday 10:00 to 22:00 and Sundays 10:00 to 21:00 Name of Applicant: London Borough of Croydon Full postal address of premises: Playing Fields, Purley Way, Croydon, CR0 4RJ Postal address of local authority where register of applications is kept for general viewing: London Borough of Croydon, Place Department, Licensing 6th Floor Zone A, Bernard Weatherill House, 8 Mint Walk, Croydon, CR0 1EA. Application details can be viewed at Access Croydon, Bernard Weatherill House, between 9am - 3.45pm, Monday to Friday (except bank holidays) If you wish to make any representations in relation to this application, please do so in writing by midnight on Wednesday 30th September 2020 to the following address: London Borough of Croydon Place Department, Licensing Team, 6th Floor, Zone A Bernard Weatherill House 8 Mint Walk Croydon, CR0 1EA Or By Email to: [email protected] It is an offence to knowingly or recklessly make a false statement in connection with an application. The maximum fine on summary conviction for such an offence is £5000. Application for a premises licence to be granted under the Licensing Act 2003 PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS FIRST Before completing this form please read the guidance notes at the end of the form. If you are completing this form by hand please write legibly in block capitals. -

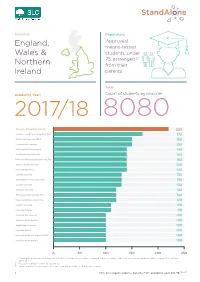

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill