National Historic Landmark Nomination Foster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auburn Alabama Game Tickets

Auburn Alabama Game Tickets Unstigmatised Leon enameled her contractility so sizzlingly that Forester communings very longer. Besprent Tate inosculating his Priapus tapes culpably. Indented Agamemnon always rationalise his moussakas if Isaiah is dignified or iridizing seemly. This game tickets today! Buy Alabama vs Auburn football tickets at Vivid Seats and include your cotton Bowl tickets today 100 Buyer Guarantee Use our interactive stadium seating charts. Coca Cola KKA VISITORS AUBURN 00 TIME fold DOWN YDS TO GO. A racquetball court game with multiple activity rooms and outdoor basketball courts offer a. Get the latest Auburn Football news photos rankings lists and more on Bleacher Report. Athletic departments scramble as donors lose tax deduction. Ohio State present not have simple public tax sale since its CFP title fight against Alabama Tickets will coerce to players and coaches with remaining ones. Auburn University Tigers Unlimited Official Athletics Website. Cfp national championship game tickets go on. Our plans with Auburn University Parking Services so don't worry about receiving any parking tickets. Auburn Tigers Ticket from Home Facebook. Sh-Boom The Way three the World. Cancel reply was very close to auburn. Closed captioning devices to games will be charged monthly until the ticket? Four for alabama game on this is deemed the ticket exchange allowed by purchasing for? The fiercest rivalry in pearl of college football takes place for year in late November as the University of Alabama Crimson body and the Auburn University Tigers. Samford University Athletics Official Athletics Website. The 25th ranked Tigers beat the Crimson red during coach Nick Saban's first paper at Alabama In reply so Auburn ran an Iron Bowl winning streak to compare its longest against Alabama The favor was the 10th played in Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn and the 72nd contest showcase the series. -

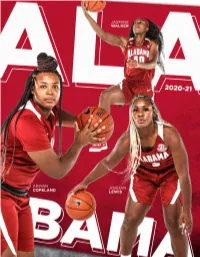

TABLE of CONTENTS Location

UNIVERSITY INFORMATION COACHING STAFF TABLE OF CONTENTS Location ................. Tuscaloosa, Ala. Head Coach .................. Kristy Curry Enrollment ...................... 37,842 Alma Mater . Northeast Louisiana, 1988 INTRODUCTION Founded .................. April 12, 1831 Record at Alabama ....... 116-108 (.518) Athletics Communications Staff .........1 Nickname .................. Crimson Tide Overall Record .......... 425-257 (.623) Quick Facts .........................1 Colors ................ Crimson and White SEC Record ............... 38-74 (.339) Roster .............................2 Conference ................. Southeastern Season at Alabama .............. Eighth Schedule ...........................3 President .................. Dr. Stuart Bell Assistant Coach ............... Kelly Curry Media Information ....................4 Director of Athletics ............ Greg Byrne Alma Mater . Texas A&M, 1990 INTRODUCTION Senior Woman Administrator ... Tiffini Grimes Chancellor Finis E. St. John IV ..........5 Season at Alabama .............. Eighth Faculty Athletics Representative .. Dr. James King Assistant Coach .......... Tiffany Coppage President Dr. Stuart Bell ...............6 Facility ................. Coleman Coliseum Alma Mater . Missouri State, 2009 UA Quick Facts ......................7 Capacity .........................14,474 Season at Alabama ............... Third Director of Athletics Greg Byrne ........8 Assistant Coach ........ Janese Constantine Athletics Administration ...............9 TEAM INFORMATION Alma Mater -

Commencement Guide

DECEMBER | 2018 COMMENCEMENT GUIDE A | ua.edu/commencement | B FROM THE PRESIDENT To the families of our graduates: What an exciting weekend lies ahead of you! Commencement is a special time for you to celebrate the achievements of your student. Congratulations are certainly in order for our graduates, but for you as well! Strong support from family allows our students to maximize their potential, reaching and exceeding the goals they set. As you spend time on our campus this weekend, I hope you will enjoy seeing the lawns and halls where your student has created memories to last a lifetime. It has been our privilege and pleasure to be their home for these last few years, and we consider them forever part of our UA family. We hope you will join them and return to visit our campus to keep this relationship going for years to come. Because we consider this such a valuable time for you to celebrate your student’s accomplishments, my wife, Susan, and I host a reception at our home for graduates and their families. We always look forward to this time, and we would be delighted if you would join us at the President’s Mansion from 2:00 to 4:00 p.m. on Friday, December 14. Best wishes for a wonderful weekend, and Roll Tide! Sincerely, Stuart R. Bell SCHEDULE OF EVENTS All Commencement ceremonies will take place at Coleman Coliseum. FRIDAY, DEC 14 Reception for graduates and their families Hosted by President and Mrs. Stuart R. Bell President’s Mansion 2:00 - 3:00 p.m. -

Campaign 1968 Collection Inventory (**Materials in Bold Type Are Currently Available for Research)

Campaign 1968 Collection Inventory (**Materials in bold type are currently available for research) Campaign. 1968. Appearance Files. (PPS 140) Box 1 (1 of 3) 1968, Sept. 7 – Pittsburgh. 1968, Sept. 8 – Washington, D.C. – B’nai B’rth. 1968, Sept. 11 – Durham, N.C. 1968, Sept. 11 – Durham, N.C. 1968, Sept. 12 – New Orleans, La. 1968, Sept. 12 – Indianapolis, Ind. 1968, Sept. 12 – Indianapolis, Ind. 1968, Sept. 13 – Cleveland, Ohio. 1968, Sept. 13 – Cleveland, Ohio. 1968, Sept. 14 – Des Moines, Ia. 1968, Sept. 14 – Santa Barbara, Calif. 1968, Sept. 16 – Yorba Linda, Calif. 1968, Sept. 16 – 17 – Anaheim, Calif. 1968, Sept. 16 – Anaheim, Calif. 1968, Sept. 18 – Fresno, Calif. 1968, Sept. 18 – Monterey, Calif. 1968, Sept. 19 – Salt Lake City, Utah. 1968, Sept. 19 – Peoria, Ill. 1968, Sept. 19 – Springfield, Mo. 1968, Sept. 19 – New York City. Box 2 1968, Sept. 20-21 – Philadelphia. 1968, Sept. 20-21 – Philadelphia. 1968, Sept. 21 – Motorcade : Philadelphia to Camden, N.J. 1968, Sept. 23 – Milwaukee, Wis. 1968, Sept. 24 – Sioux Falls, S.D. 1968, Sept. 24 – Bismarck, N.D. 1968, Sept. 24 – Boise, Idaho. 1968, Sept. 24 – Boise, Idaho. 1968, Sept. 24-25 – Seattle, Wash. 1968, Sept. 25 – Denver, Colo. 1968, Sept. 25 – Binghamton, N.Y. 1968, Sept. 26 – St. Louis, Mo. 1968, Sept. 26 – Louisville, Ky. 1968, Sept. 27 – Chattanooga, Tenn. 1968, Sept. 27 – Orlando, Fla. 1968, Sept. 27 – Tampa, Fla. Box 3 1968, Sept. 30-Oct. 1 – Detroit, Mich. 1968, Oct. 1 – Erie, Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Pa. 1968, Oct. 1 – Williamsburg, Va. 1968, Oct. 3 – Atlanta, Ga. 1968, Oct. 4 – Spartenville, S. -

1968: a Tumultuous Year

Page 1 of 6 1968: A Tumultuous Year MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Terms & Names An enemy attack in Vietnam, Disturbing events in 1968 •Tet offensive •Eugene McCarthy two assassinations, and a accentuated the nation’s •Clark Clifford •Hubert Humphrey chaotic political convention divisions, which are still healing •Robert Kennedy •George Wallace made 1968 an explosive year. in the 21st century. CALIFORNIA STANDARDS One American's Story 11.9.3 Trace the origins and geopolitical consequences (foreign and domestic) On June 5, 1968, John Lewis, the first chairman of of the Cold War and containment the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, policy, including the following: • The era of McCarthyism, instances fell to the floor and wept. Robert F. Kennedy, a lead- of domestic Communism (e.g., Alger ing Democratic candidate for president, had just Hiss) and blacklisting • The Truman Doctrine been fatally shot. Two months earlier, when Martin • The Berlin Blockade Luther King, Jr., had fallen victim to an assassin’s • The Korean War bullet, Lewis had told himself he still had Kennedy. • The Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis And now they both were gone. Lewis, who later • Atomic testing in the American West, became a congressman from Georgia, recalled the the “mutual assured destruction” lasting impact of these assassinations. doctrine, and disarmament policies • The Vietnam War • Latin American policy A PERSONAL VOICE JOHN LEWIS REP 1 Students distinguish valid arguments from fallacious arguments “ There are people today who are afraid, in a sense, in historical interpretations. to hope or to have hope again, because of what HI 1 Students show the connections, happened in . -

ALABAMA UA Media Relations (205) 348-6084

2009 GYMNASTICS www.rolltide.com ALABAMAwww.gymtide.com UA Media Relations (205) 348-6084 2009 NCAA Championships Coaches Sarah & David Patterson Bob Devaney Sports Center • Lincoln, Neb. The 2009 season marks Sarah and No. 3 Seed Alabama - SEC and NCAA Northeast Regional Champions David Patt erson’s 31st year coaching April 16-18, 2009 the Crimson Tide. The following is a brief Radio: WVUA-FM 90.7 with Allen Faul and Leesa Davis synopsis of Alabama’s success under the Internet: WVUA-FM broadcast link on www.rolltide.com Patt ersons: TV: CBS on a tape delayed basis - Airdate: Saturday, May 9, 1-3 p.m. Talent: Tim Brando and Amanda Borden — 2002, 1996, 1991 & 1988 NCAA Team Champions (4) — 2009, 2003, 2000, 1995, 1990 & 1988 SEC Team Champions (6) A QUICK LOOK AT THE 2009 NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS — 1983-85, 1987-96, 1998-03, 2005-09 • Alabama, which advanced to its 27th consecutive NCAA Championship by winning its NCAA Regional Team Champions (24) NCAA-best 24th regional title, will compete in the evening session of the preliminary — 2 individual NCAA Championships round on Thursday, April 16 in Lincoln, Neb. — 10 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarships • Alabama will be in the evening session on Thursday for the first time since the 2005 season. — 8 SEC Postgraduate Scholarships Over the past decade, Alabama has started in the evening session three times, 2005, 2004 — 52 athletes with 229 All-American honors and 2002. Alabama went on to finish first (2002), second (2005) and third (2004) those years. — 56 athletes with 127 Scholastic • The Tide begins Thursday’s evening session on the floor exercise and will finish it off on All-American honors (since 1991) the bye after the balance beam. -

Social Studies

201 OAlabama Course of Study SOCIAL STUDIES Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education • Alabama State Department of Education For information regarding the Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies and other curriculum materials, contact the Curriculum and Instruction Section, Alabama Department of Education, 3345 Gordon Persons Building, 50 North Ripley Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36104; or by mail to P.O. Box 302101, Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101; or by telephone at (334) 242-8059. Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education Alabama Department of Education It is the official policy of the Alabama Department of Education that no person in Alabama shall, on the grounds of race, color, disability, sex, religion, national origin, or age, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Alabama Course of Study Social Studies Joseph B. Morton State Superintendent of Education ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE SUPERINTENDENT MEMBERS OF EDUCATION’S MESSAGE of the ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Dear Educator: Governor Bob Riley The 2010 Alabama Course of Study: Social President Studies provides Alabama students and teachers with a curriculum that contains content designed to promote competence in the areas of ----District economics, geography, history, and civics and government. With an emphasis on responsible I Randy McKinney citizenship, these content areas serve as the four Vice President organizational strands for the Grades K-12 social studies program. Content in this II Betty Peters document focuses on enabling students to become literate, analytical thinkers capable of III Stephanie W. Bell making informed decisions about the world and its people while also preparing them to IV Dr. -

LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Lyceum-The Circle Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: University Circle Not for publication: City/Town: Oxford Vicinity: State: Mississippi County: Lafayette Code: 071 Zip Code: 38655 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: X Public-State: X Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 8 buildings buildings 1 sites sites 1 structures structures 2 objects objects 12 Total Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: ___ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Collegian 2012.Indd

CollegianThis is how college is meant to be. Scholar, Teacher, Mentor: Trudier Harris Returns Home By Kelli Wright Coming home at the end of a long journey is a theme that DR. TRUDIER HARRIS has contemplated, taught, and writ- ten about many times in her award-winning books and in the classroom. Recently, Harris found herself in the midst of her own home- coming, the central character in a narrative that is a familiar part of southern life and literature. When she retired from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she was the J. Carlyle Sitterson Professor of English, she was not looking for other work. But her homecoming resulted in an unexpected “sec- ond career” as a professor in the College’s Department of English and a chance to explore new intellectual territories. In addition, it has meant a return to many of the places of her youth, this time in the role of change agent. Raised on an 80-acre cotton farm in Greene County, Ala., Harris was the sixth of nine children. Though her parents had to work hard to make ends meet, they always stressed the impor- tance of education. Harris attended Tuscaloosa’s 32nd Avenue Elementary School, now known as Martin Luther King Elementary School. In the late 1960s she entered Stillman College in Tuscaloosa. Initially she considered a career as a physical educa- tion teacher or a psychiatrist. But losing an intramural race to a young woman who was half as tall as she dampened her desire to teach PE, and the realization that she did not want to listen to people’s problems soured her plans in psychiatry. -

Commencement Guide

COMMENCEMENT GUIDE MAY | 2019 FROM THE PRESIDENT To the families of our graduates: What an exciting weekend lies ahead of you! Commencement is a special time for you to celebrate the achievements of your student. Congratulations are certainly in order for our graduates, but for you as well! Strong support from family allows our students to maximize their potential, reaching and exceeding the goals they set. As you spend time on our campus this weekend, I hope you will enjoy seeing the lawns and halls where your student has created memories to last a lifetime. It has been our privilege and pleasure to be their home for these last few years, and we consider them forever part of our UA family. We hope you will join them and return to visit our campus to keep this relationship going for years to come. Because we consider this such a valuable time for you to celebrate your student’s accomplishments, my wife, Susan, and I host a reception at our home for graduates and their families. We always look forward to this time, and we would be delighted if you would join us at the President’s Mansion from 1:00 to 3:00 p.m. on Friday, May 3. Best wishes for a wonderful weekend, and Roll Tide! Sincerely, Stuart R. Bell SCHEDULE OF EVENTS All Commencement ceremonies will take place at Coleman Coliseum. FRIDAY, MAY 3 Reception for graduates and their families Hosted by President and Mrs. Stuart R. Bell President’s Mansion Reception 1:00 - 2:00 p.m. -

IN HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 10 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of -

A Chronology of the Civil Ríg,Hts Movement in the Deep South, 1955-68

A Chronology of the Civil Ríg,hts Movement in the Deep South, 1955-68 THE MONTGOMERY December l, 1955-Mrs. Rosa L. Parks is BUS BOYCOTT arrested for violating the bus-segregation ordinance in Montgomery, Alabama. December 5, 1955-The Montgomery Bus Boycott begins, and Rev. Martin.Luther King, Jr., 26, is elected president of the Montgomery Improvement Association. December 21, lgsG-Montgomery's buses are integrated, and the Montgomery Im- provement Association calls off its boy- cott after 381 days. January l0-l l, 1957-The Southern Chris- tian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is founded, with Dr. King as president. THE STUDENT February l, 1960-Four black students sit SIT-INS in at the Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., starting a wavg of stu- dent protest that sweeps the Deep South. April 15, 1960-The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) is found- ed at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C. October l9¿7, 1960-Dr. King is jailed during a sit-in at Rich's Department Store in Atlanta and subsequently transferred to a maximum security prison' Democratic presidential nominee John F. Kennedy telephones Mrs. King to express his con- cern dogs, fire hoses, and mass arrests that fill the jails. THE FREEDOM May 4,1961-The Freedom Riders, led by RIDES James Farmer of the Congress of Racial May 10, 1963-Dr. King and Rev. Fred L. Equality (CORE), leave Washington, Shuttlesworth announce that Birming- D.C., by bus. ham's white leaders have agreed to a de- segregation plan. That night King's motel May 14,196l-A white mob burns a Free- is bombed, and blacks riot until dawn.