Ariel 35(3-4)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sleepy Hollow Experience

Contact: Ryan Oliveti, Artistic Associate 770-463-1110 | [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Serenbe Playhouse Presents THE SLEEPY HOLLOW EXPERIENCE Now In Its 5th SOLD OUT Year A New Adaptation by Brian Clowdus With Dialogue Assistance by Rachel Teagle Direction by Ryan Oliveti September 28th – November 5th Atlanta (September 2017) – Serenbe Playhouse, recipient of the prestigious American Theatre Wing grant, and recently honored with the most Suzi Bass Awards for a musical in Atlanta (Miss Saigon), is pleased to present THE SLEEPY HOLLOW EXPEREINCE. Directed by Ryan Oliveti, the show opens on September 28th and runs to November 5th. THE SLEEPY HOLLOW EXPERIENCE will be produced at The Horseman’s Meadow in Serenbe. ABOUT THE SLEEPY HOLLOW EXPERIENCE As autumn cools the steaming earth and leaves begin to turn, we’re bringing back our favorite fall fright fest: The Sleepy Hollow Experience. Following four sold out seasons and recognition as one of the ‘Top Five Halloween Plays in the Country’ by American Theatre Magazine, patrons will enjoy a fresh adaptation by Serenbe Playhouse’s Brian Clowdus. This immersive Halloween experience is sure to have heads rolling. “It is hard to believe that we are entering our fifth year of The Sleepy Hollow Experience,” says Oliveti. “It feels like just yesterday that Brian Clowdus was on my phone asking me to Assistant Direct the very first production of this show. I never would have guessed that 5 years later I’d be standing in a field ready to remount this tale. I could not be more excited for its return and its lasting legacy as an Atlanta Halloween tradition.” BRAND NEW THIS YEAR, The Sleepy Hollow Experience is going family friendly each Sunday in October at 2pm! Join us starting at 1pm for fall activities including: a pumpkin patch, pumpkin decorating, s’more making, fall games, food & drink. -

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection Finding Aid Collection Overview Title: The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012 (bulk 1808-1896) Creator: Osterweis, Rollin G. (Rollin Gustav), 1907- Extent : 159 volumes; 1 linear foot of archival material Repository: Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives Abstract: This collection holds 159 volumes that make up the Rollin G. Osterweis Collection of Irving Editions and Irvingiana. It also contains one linear foot of archival materials related to the collection. Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Item title. (date) City: Publisher [if applicable]. The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012, (Date of Access). Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives. Historic Hudson Valley. Provenance: This collection was created by Rollin Gustav Osterweis and donated to Historic Hudson Valley by Ruth Osterweis Selig. 18 December 2012. Access: This collection is open for research with some restrictions based on the fragility of certain materials. Research restrictions for individual items are available on request. For more information contact the Historic Hudson Valley librarian, Catalina Hannan: [email protected]. Copyright: Copyright of materials belongs to Historic Hudson Valley. Permission to reprint materials must be obtained from Historic Hudson Valley. The collection contains some material copyrighted by other organizations and individuals. It is the responsibility of the researcher to obtain all permission(s) related to the reprinting or copying of materials. Processed by: Christina Neckles Kasman, February-August 2013 Osterweis Irving Collection - 1 Biographical Note Rollin Gustav Osterweis was a native of New Haven, Connecticut, where his grandfather had established a cigar factory in 1860. -

World Premiere Teen Adaptation of Sleepy Hollow Creeps to Dallas Children's Theater

MEDIA RELEASE Contact: Sherry Ward [email protected] 214-978-0110 ext. 143 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 17, 2015 World Premiere teen adaptation of Sleepy Hollow creeps to Dallas Children’s Theater (Dallas, TX) The legendary tales of Washington Irving arrive at Dallas Children’s Theater just in time for Halloween with the world premiere of THE GHOSTS OF SLEEPY HOLLOW (GHOSTS) by Philip Schaeffer, son of longtime DCT employees Nancy and Karl Schaeffer. The show will be pre- sented by the Teen Scene Players October 16 - 30 in the Studio Theater. You may have heard of Ichabod Crane and the Headless Horseman, but Sleepy Hollow has so many more frightening secrets for families and their teens to discover. GHOSTS takes audiences deep into the haunting woods of Sleepy Hollow to see why the terrifying tales of Washington Irving have been favorites for fireside spookfests for over a hundred years. The Studio Theater will be transformed into a wild, fun romp through a hair-raising nightmare that might just scare the heads off its audience. Director and DCT Associate Artistic Director Artie Olaisen directs the teen cast in this fun and frightening new play. Olaisen shares the process of creating this production, saying, “Any new script is always exciting to work on. It has been a particular pleasure to work with playwright Philip Schaeffer as he grew up here at the DCT. We had worked together on the previous Academy pro- duction of GHOULS AND GRAVEYARDS in which I asked him to submit an original short dramatic piece to be included along with the works of Poe and W.W. -

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow Adapted by Catherine Bush from the Short Story by Washington Irving *Especially for Grades 4-11

Study Guide prepared by Catherine Bush Barter Playwright-in-Residence The Legend of Sleepy Hollow Adapted by Catherine Bush from the short story by Washington Irving *Especially for Grades 4-11 By the Barter Players, Barter’s Smith Theatre Fall, 2019 On tour January thru March, 2020 (NOTE: standards are included for reading the story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, seeing a performance of the play, and completing the study guide.) Virginia SOLs English – 4.1, 4.2, 4.4, 4.5, 4.7, 4.9, 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 5.5, 5.7, 5.9, 6.1, 6.2, 6.4, 6.5, 6.7, 6.9, 7.1, 7,2, 7.4, 7.5, 7.7, 7.9, 8.1, 8.2, 8.4, 8.5, 8.7, 8.9, 9.1, 9.3, 9.4, 9.6, 9.8, 10.1, 10.3, 10.4, 10.6, 10.8, 11.1, 11.3, 11.4, 11.6, 11.8 Theatre Arts – 6.5, 6.7, 6.18, 6.21, 7.6, 7.18, 7.20, 8.5, 8.12, 8.18, 8.22, TI.10, TI.11, TI.13, TI.17, TII.9, TII.12, TII.15, TII.17, TIII.12 Tennessee/North Carolina Common Core State Standards English Language Arts – Reading Literature: 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.7, 5.4, 5.9, 6.4, 6.7, 6.10, 7.4, 7.7, 7.10, 8.4, 8.7, 8.10, 9-10.4, 9-10.10, 11-12.4, 11-12.7, 11-12.10 English Language Arts – Writing: 4.3, 4.7, 5.3, 5.9, 6.1, 6.4, 6.6, 6.7, 7.1, 7.3, 7.7, 8.1, 8.3, 8.7, 9-10.1, 9-10.3, 9-10.7, 11-12.2, 11-12.1, 11-12.3, 11-12.7 Tennessee Fine Arts Curriculum Standards Theatre –4.T.P3, 4.T.Cr2, 4.T.Cr3, 4.T.R1, 4.T.Cn1, 5.T.P3, 5.T.Cr2, 5.T.R1 Theatre 6-8 – 6.T.Cr2, 6.T.R1, 6.T.R3, 7.T.P3, 7.T.Cr2, 7.T.R3, 8.T.P3, 8.T.R1, 8.T.R3 Theatre 9-12 – HS3.T.Cr3, HS1.T.R1, HS2.T.R1, HS1.T.R1, HS1.T.R2, HS1.T.R3 North Carolina Essential Standards Theatre Arts – 4.C.1, 4.A.1, 5.A.1, 6.A.1, 6.C.2, 6.CU.2, 7.C.2, 7.A.1. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating' adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Art of Literary Tourism: an Approach to Washington Irvings "Sketch Book"

The Art of Literary Tourism: An Approach to Washington Irvings "Sketch Book" DAVID SEED WEN The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon first appeared in Britain it was received with magisterial surprise by Francis Jeffrey who saw it as a turning-point in American literature. He expresses surprise that a work written by an American and originally published in America "should be written throughout with the greatest care and accuracy, and worked up to great purity and beauty of diction," and then continues: It is the first American work, we rather think of any description, but certainly the first purely literary production, to which we could give this praise; and we hope and trust that we may hail it as the harbinger of a purer and juster taste.... for the writers of that great and intelligent country.1 Jeffrey hesitates here because, as other critics of the 1818-1820 period recognized, the only other American work which might measure up to this praise was Franklin's Autobiography. It is particularly significant that he should point out the historical importance of The Sketch Book in Anglo-American literary relations before he comments on the book's intrinsic merits. William Cullen Bryant followed exactly the same procedure in his i860 address on Irving.2 Of course it is theoretically possible that Irving's miscellany might have gained this recognition, a recognition which masks the origin of its status as an American classic, without external circumstances having any direct effect on the book itself. But such is not the case. In Bracebridge Hall (1822), the sequel to The Sketch Book, Irving expresses amused surprise at the way the earlier work was received: "It has been a matter of marvel, that a man from the wilds of America should express himself in 68 DAVID SEED tolerable English."3 In both works Irving gently ridicules the prejudiced expectations on the part of an average British reader that he will have to cope with some kind of wild or uncouth writer by adopting a stance of conscious urbanity. -

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow Study Guide Copy

ALWAYS FREE LITERARY CLASSIC THE LEGEND OF SLEEPY HOLLOW BRIGHT STAR CHILDREN’S THEATRE, LLC*BRIGHT STAR TOURING THEATRE About the Production! This is our hilarious version of the infamous literary classic by the literary genius Washington Irving! The story follows the bumbling yet endearing Ichabod Crane, the beautiful and elegant Katrina Van Tassel and, of course, the bullying Brom Bones. They work to bring new life to this classic tale that is credited as being America’s first work of fiction! Your young audience will love seeing audience volunteers and one unsuspecting teacher join the actors on-stage for an impromptu Sleepy Hollow choir practice and the arrival of our not-too-scary Headless Horseman! Our approach to the tale is funny and entertaining, yet lovable WASHINGTON IRVING and approachable for your young The author of our spooky tale is a early 19th century... whew! In his audience. man named Washington Irving. He latter years, President John Tyler was born on April 3, 1783 in appointed Mr. Irving as the THEMES YOU MAY RECOGNIZE IN Manhattan, NY. His family were of Minister of Spain and he was very THIS PROGRAM: Scottish-English decent and they good at his job. He is also well- *Literary immigrated to America. He became known for another tale you may *Anti-Bullying famous for being an author, but he have heard of called ‘Rip Van *Holiday was also an essayist, historian, Winkle’ about a man who fell asleep *Character-Education biographer and diplomat of the for about 20 years! Other Famous Authors & Irving CRITICS who lived in the same time period! GEORGE WILLIAM CURTS was an EDGAR ALLAN POE, famous American HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW, American writer, public speaker and Irving author and poet, was not much of a fan of the American poet and educator, said American advocate who stated, “there is not a young Washington Irving. -

“Sleepy Hollow” Ichabod Crane: Comparing and Contrasting Different Medium Lesson Overview

“Sleepy Hollow” Ichabod Crane: Comparing and Contrasting Different Medium Lesson Overview Overview: Students will read an adapted version of Washington Irving’s “Sleepy Hollow”. Before students read the story, they will analyze a cartoon sketch of the character Ichabod Crane. Using an analysis tool, the students will analyze the sketch noting anything unique. The lesson will continue with discussion of the classroom, as well as a quick lesson on classrooms in the 18th century. By the end of the lesson, students will have a better understanding of how fiction is influenced by real events and people, as well as being able to compare similar content in different mediums. Grade Range: 6-8 Objective: After completing this activity, students should be able to: Understand the history behind a short story prior to reading the material. Differentiate between the historical fiction of the short story “Sleepy Hollow” and the historical fact. Compare and contrast different mediums containing similar content (i.e. short story and cartoon sketch). Time Required: Two class periods of 45 minutes. Discipline/Subject: Short Story/Literature Topic/Subject: Culture, Folklife and Literature Era: The New Nation, 1783-1815 Standards Illinois Learning Standards: Common Core Standard: Standards for ELA &Literacy in History/ Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects: 7th Grade Students: Goal #8: Compare and contrast a fictional portrayal of a time, place, or character and a historical account of the same period as a means of understanding how authors -

Horizons School Matinee Series

2009-2010 Educator’s Resource Guide Horizons School Matinee Series Sleepy Hollow Monday, October 19, 2009 10:00 a.m./ 12:30 p.m. Celebrating 25 Years of Professional Performing Arts for K-12 Students Horizons School Matinee Series Thank you for joining us as we celebrate the 25th anniversary season of the Horizons School Matinee Series. We are proud to announce that over half a million students have experienced a professional performing arts event with us since the inception of this program. This season continues the tradition of providing great performances to enhance learning, fi re imaginations, and reinforce school curriculum in meaningful ways. Thank you for expanding children’s minds and sharing with them the joy of the performing arts! This resource guide has been designed to help you prepare your students with before activities that help them engage in the performance and after activities that encourage them to evaluate the performance and make relevant personal and academic connec- tions. Within the guide you will fi nd a variety of activities that can be used to enhance the core subject areas as well as the creative arts. Wisconsin Academic Standards are listed at the end of the guide to help you link the activities to your lesson plans. The materials in this guide refl ect the grade range recommended by the performing arts group. As teachers, you know best what the needs and abilities of your students are; therefore, please select and/or adapt any of the material to best meet the needs of your particular group of students. -

Irving's Posterity

IRVING’S POSTERITY BY MICHAEL WARNER Like the narrators of all his major books—Geoffrey Crayon, Diedrich Knickerbocker, Jonathan Oldstyle, Fray Antonio Agapida—Washington Irving was a bachelor. In a sketch called “Bachelors” he wrote, “There is no character in the comedy of human life that is more difficult to play well, than that of an old Bachelor.”1 Reinventing that role was the project he took on, more or less consciously, from an early age. As a young man, he belonged to an intimate circle of bachelors (“Cockloft,” they called it) with whom he wrote Salmagundi; when the others married, he wrote with unusual passion about his abandonment. He then came to regard his writing career as an alternative to marriage. As an old man, he maintained himself at Sunnyside, his estate on the Hudson, as a surrogate patriarch to his nieces, his bachelor brother, miscellaneous dependents, and American letters in general. It was a role he played with success; before his death he was almost universally credited as “Patriarch of American literature” and “literary father of his country,” a pseudo-paternity most famously illustrated in the so-called Sunnyside portrait. When he died, he would be eulogized as “the most fortunate old bachelor in all the world.”2 Yet bachelorhood was something he consistently regarded as anoma- lous, problematic, and probably immoral. Irving claimed as early as 1820 that his natural inclination was to be “an honest, domestic, uxorious man,” and that matrimony was indispensable to happiness.3 Over twenty years later, he wrote, “I have no great idea of bachelor hood and am not one by choice. -

Sleepy Hollow: Riparte Con Un Crossover Con Bones E Una New

LUNEDì 18 GENNAIO 2016 Sleepy Hollow ritorna con la sua terza stagione in anteprima assoluta per l'Italia dal 18 gennaio, ogni lunedì alle 21 su FOX (canale 106 e 112 di Sky). Ispirata al racconto di un grande autore della letteratura americana, Sleepy Hollow: riparte con un Washington Irving, da cui il genio di Tim Burton ha tratto il film con crossover con Bones e una new Johnny Depp e Christina Ricci, ritorna la nuova stagione inedita di entry nel cast SLEEPY HOLLOW. Sono passati nove mesi e una nuova minaccia incombe su Sleepy In prima visione assoluta dal 18 gennaio, ogni Hollow: Pandora (Shannyn Sossamon, Wayward Pines). Questo lunedì alle 21 su FOX misterioso personaggio riesce a imprigionare il Cavaliere Senza Testa nel vaso di Pandora, il mitologico contenitore di tutti i mali del mondo, e a impossessarsi dei poteri di un demone che paralizza le sue vittime con la CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI paura prima di ucciderle. Nel frattempo, Ichabod Crane (Tom Mison) e Abbie Mills (Nicole Beharie), diventata agente dell'FBI, si riuniscono per far luce su un misterioso omicidio che sembra proprio essere opera di questo malvagio [email protected] essere. SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Grande protagonista della terza stagione di Sleepy Hollow è sicuramente il chiacchieratissimo crossover con la serie tv Bones (la cui 10° stagione verrà trasmessa prossimamente su FOX). Un cadavere decapitato viene ritrovato in una chiesa abbandonata di Washington: Ichabod e Abbie sono convinti che il corpo senza testa sia collegato con alcuni omicidi rimasti irrisolti a Sleepy Hollow e decidono dunque di rivolgersi alla dottoressa Temperance "Bones" Brennan (Emily Deschanel) e all'agente speciale Seeley Booth (David Boreanaz) per far luce sull'accaduto. -

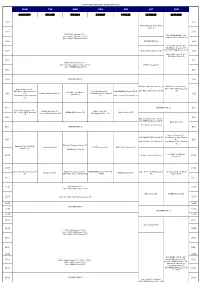

FOX Program Schedule August(Easiness)

FOX Program Schedule August(easiness) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 3.10.17.24.31 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 4:00 4:00 American Horror Story: Freak Show (S) 4:30 4:30 NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / 7th~ NAVY NCIS Season7 (S) / FOX IKKIMI SUNDAY JUL. 25th~ NAVY NCIS Season8 (S) 2nd NAVY NCIS Season12 (S) 5:00 INFORMATION (J) / 5:00 FOX IKKIMI SUNDAY AUG. 9th NCIS:LA Season5 (S) / 5:30 Modern Family Season5 (S) 16th NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) 5:30 / 23rd Castle Season6 (S) / 30th Battle Creek (S) 6:00 6:00 Sleepy Hollow Season2 (S) / 13th~ Da Vinci's Demons Season2 (S) / BONES Season9 (B) 27th~ BONES Season8 (S) 6:30 6:30 7:00 INFORMATION (J) 7:00 Da Vinci's Demons Season2 (S) NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / New Girl Season4 (S) / / 9th~ NAVY NCIS Season12 24th Modern Family Season5 New Girl Season4 (S) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) 29th Major Crimes Season3 (S) (S) How I Met Your Mother (S) / Modern Family Season5 (S) 27th Modern Family Season5 / 7:30 Season5 (S) 7:30 31st Modern Family Season6 (S) 28th 2 Broke Girls Season2 (S) (S) 8:00 INFORMATION (J) 8:00 NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / NCIS:LA Season5 (S) / Battle Creek (B) / 10th~ NAVY NCIS Season12 HOMELAND Season1 (S) Castle Season 6 (S) 11th~ NCIS:LA Season6 (S) 27th Wayward Pines (S) (S) 8:30 8:30 New Girl Season4 (S) (~9:00) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) Battle Creek (S) / 8th~ NCIS:LA Season6 (S) 9:00 INFORMATION (J) 9:00 New Girl Season4 (S) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) 23rd Modern Family Season5 9:30 / (S) / 9:30 29th 2 Broke Girls Season2 (S) 30th Modern Family