Yusef Komunyakaa: Questioning Traditional Metaphors of Light and Darkness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

GÜNTER KONRAD Visual Artist 2 Contents

GÜNTER KONRAD visual artist 2 contents CURRICULUM VITAE 4 milestones FRAGMENTS GET A NEW CODE 7 artist statement EDITIONS 8 collector‘s edition market edition commissioned artwork GENERAL CATALOG 14 covert and discovered history 01 - 197 2011 - 2017 All content and pictures by © Günter Konrad 2017. Except photographs page 5 by Arne Müseler, 80,81 by Jacob Pritchard. All art historical pictures are under public domain. 3 curriculum vitae BORN: 1976 in Leoben, Austria EDUCATION: 2001 - 2005 Multi Media Art, FH Salzburg DEGREE: Magister (FH) for artistic and creative professions CURRENT: Lives and works in Salzburg as a freelance artist milestones 1999 First exhibition in Leoben (Schwammerlturm) 2001 Experiments with décollages and spray paintings 2002 Cut-outs and rip-it-ups (Décollage) of billboards 2005 Photographic documentation of décollages 2006 Overpaintings of décollages 2007 Photographic documentation of urban fragments 2008 Décollage on furniture and lighting 2009 Photographic documentation of tags and urban inscriptions 2010 Combining décollages and art historical paintings 2011 First exhibition "covert and discovert history" in Graz (exhibition hall) 2012 And ongoing exhibitions and pop-ups in Vienna, Munich, Stuttgart, | Pörtschach, Wels, Mondsee, Leoben, Augsburg, Nürnberg, 2015 Purchase collection Spallart 2016 And ongoing commissioned artworks in Graz, Munich, New York City, Salzburg, Serfaus, Singapore, Vienna, Zirl 2017 Stuttgart, Innsbruck, Linz, Vienna, Klagenfurt, Graz, Salzburg and many others ... OTHERS: Exhibition at MAK Vienna Digital stage design, Schauspielhaus Salzburg Videoscreenings in Leipzig, Vienna, Salzburg, Graz, Cologne, Feldkirch Interactive Theater Performances, Vienna (Brut) and Salzburg (Schauspielhaus), organizer of Punk/Garage/Wave concerts... 4 5 6 fragments get a new code The best subversion is to disfigure codes instead of destroying them. -

Keith Carlock

APRIZEPACKAGEFROM 2%!3/.34/,/6%"),,"25&/2$s.%/.42%%3 7). 3ABIANWORTHOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 'ET'OOD 4(%$25--%23/& !,)#)!+%93 $!.'%2-/53% #/(%%$ 0,!.4+2!533 /.345$)/3/5.$3 34!249/52/7. 4%!#().'02!#4)#% 3TEELY$AN7AYNE+RANTZS ,&*5)$"3-0$,7(9(%34(%-!.4/7!4#( s,/52%%$34/.9h4(5.$%2v3-)4( s*!+),)%"%:%)4/&#!. s$/5",%"!3335"34)454% 2%6)%7%$ -/$%2.$25--%2#/- '2%43#(052%7//$"%%#(3/5,4/.%/,$3#(//,3*/9&5,./)3%%,)4%3.!2%3%6!.34/-0/7%2#%.4%23 Volume 35, Number 3 • Cover photo by Rick Malkin CONTENTS 48 31 GET GOOD: STUDIO SOUNDS Four of today’s most skilled recording drummers, whose tones Rick Malkin have graced the work of Gnarls Barkley, Alicia Keys, Robert Plant & Alison Krauss, and Coheed And Cambria, among many others, share their thoughts on getting what you’re after. 40 TONY “THUNDER” SMITH Lou Reed’s sensitive powerhouse traveled a long and twisting musical path to his current destination. He might not have realized it at the time, but the lessons and skills he learned along the way prepared him per- fectly for Reed’s relentlessly exploratory rock ’n’ roll. 48 KEITH CARLOCK The drummer behind platinum-selling records and SRO tours reveals his secrets on his first-ever DVD, The Big Picture: Phrasing, Improvisation, Style & Technique. Modern Drummer gets the inside scoop. 31 40 12 UPDATE 7 Walkers’ BILL KREUTZMANN EJ DeCoske STEWART COPELAND’s World Percussion Concerto Neon Trees’ ELAINE BRADLEY 16 GIMME 10! Hot Hot Heat’s PAUL HAWLEY 82 PORTRAITS The Black Keys’ PATRICK CARNEY 84 9 REASONS TO LOVE Paul La Raia BILL BRUFORD 82 84 96 -

Writ 205A, Poetry

ENGLISH 200: INTRODUCTION TO POETRY WRITING Fall Semester 2013 Tu/Th 9:30–10:45 PM, Clough Hall 300 CRN: 14521 Dr. Caki Wilkinson Office: Palmer 304 Phone: x3426 Office hours: Tu/W/Th 11:00 AM – noon, and by appt. Email: [email protected] TEXTS Harmon, William, ed. The Poetry Toolkit. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. McClatchy, J.D., ed. The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry. 2nd edition. New York: Vintage Books, 2003. ―As a rule, the sign that a beginner has a genuine original talent is that he is more interested in playing with words than in saying something original; his attitude is that of the old lady, quoted by E.M. Forster—‗How can I know what I think until I see what I say?‘‖ – W.H. Auden COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is designed to help participants broaden their understanding and appreciation of the craft of poetry. Bearing in mind that the English word poetry derives from the Greek poēisis (an act of ―making‖) we will approach writing as a means of producing ideas rather than simply expressing them. Throughout the semester we will be, as Auden put it, ―playing with words,‖ and our work will focus on elements of poetry such as diction, rhythm, imagery, and arrangement. We will read a large sampling of contemporary poetry; we will do a lot of writing, from weekly exercises to polished poems; we will discuss this writing in workshop format and learn how to make it better. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Nine writing exercises Six poems and a final portfolio A poetic catalog consisting of ten reading lists Memorization of fourteen lines of poetry Active participation in workshop and written responses to poems Writing exercises. -

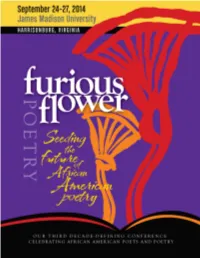

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE INCORPORATING MULTIPLE HISTORIES: THE POSSIBILITY OF NARRATIVE RUPTURE OF THE ARCHIVE IN V. AND BELOVED A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By LEANN MARIE STEVENS-LARRE Norman, Oklahoma 2010 INCORPORATING MULTIPLE HISTORIES: THE POSSIBILITY OF NARRATIVE RUPTURE OF THE ARCHIVE IN V. AND BELOVED A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY _____________________________________________ Dr. Timothy S. Murphy, Chair _____________________________________________ Dr. W. Henry McDonald _____________________________________________ Dr. Francesca Sawaya _____________________________________________ Dr. Rita Keresztesi _____________________________________________ Dr. Julia Ehrhardt © Copyright by LEANN MARIE STEVENS-LARRE 2010 All Rights Reserved. This work is dedicated to the woman who taught me by her example that it was possible. Thank you, Dr. Stevens, aka, Mom. Acknowledgements I am and will always be genuinely grateful for the direction of my dissertation work by Tim Murphy. He was thorough, rigorous, forthright, always responding to my drafts and questions with lightening speed. Whatever is good here is based on his guidance, and whatever is not is mine alone. I know that I would not have been able to finish this work without him. I also appreciate the patience and assistance I received from my committee members, Henry McDonald, Francesca Sawaya, Rita Keresztesi, and Julia Ehrhardt. I have benefitted greatly from their experience, knowledge and encouragement. Henry deserves special recognition and heartfelt thanks for sticking with me through two degrees. I would also like to thank Dr. Yianna Liatsos for introducing me to ―the archive.‖ I most sincerely thank (and apologize to) Nancy Brooks for the tedious hours she spent copy-editing my draft. -

Sympathy and Postwar American Poetry

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2013 12:00 AM Feeling With Imagination: Sympathy and Postwar American Poetry Timothy A. DeJong The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Stephen Adams The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Timothy A. DeJong 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation DeJong, Timothy A., "Feeling With Imagination: Sympathy and Postwar American Poetry" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1491. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1491 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEELING WITH IMAGINATION: SYMPATHY AND POSTWAR AMERICAN POETRY (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Timothy A. DeJong Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Timothy A. DeJong 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines how sympathy, defined as the act of “feeling with” another, develops within American poetics from 1950-1965 both -

The Oral Histories of Three Retired African American

THE ORAL HISTORIES OF THREE RETIRED AFRICAN AMERICAN SUPERINTENDENTS FROM GEORGIA by GARRICK ARION ASKEW (UNDER the Direction of Sally J. Zepeda) ABSTRACT This study included the oral histories of three retired African American superintendents who were natives of Georgia. The participants had professional careers that collectively spanned 54 years, beginning as teachers and moving into administrative positions including the superintendency. This study used archival documents, newspaper reports, and research and literature on segregation, desegregation, and career mobility to provide context for the participants’ oral histories. Three research questions guided the interviews for this study: 1. How did each of the participants first enter education? 2. How were the participants able to ascend to the superintendency in light of challenges that they faced as African American school administrators? 3. What was the experience of being an African American educator and school administrator in Georgia school districts? The data revealed common factors in the career experiences of the participants. Common factors included childhood mentoring in segregated K-12 schools, segregated schools as extended families, self image and life skills training, and academic preparation at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Other common factors influencing the participants were professional mentoring at HBCUs, experiences with career mobility processes, school desegregation as the impetus for advancement, financial challenges of the superintendency, -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 115, 1995-1996, Subscription, Volume 02

BOSTON ii_'. A4 SYMPHONY . II ORCHESTRA A -+*\ SEIJIOZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 9 6 S E SON The security of a trust, Fidelity investment expertise. A CLjmIc Composition Just as a Beethoven score is at its Fidelity i best when performed by a world- Pergonal ** class symphony — so, too, should your trust assets be managed by Trudt r a financial company recognized Serviced globally for its investment expertise. Fidelity Investments. hat's why Fidelity now offers a naged trust or personalized estment management account ** »f -Vfor your portfolio of $400,000 or ^^ more. For more information, visit -a Fidelity Investor Center or call Fidelity Pergonal Triut Serviced at 1-800-854-2829. Visit a Fidelity Investor Center Near You: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments" SERVICES OFFERED ONLY THROUGH AUTHORIZED TRUST COMPANIES. TRUST SERVICES VARY BY STATE. FIDELITY BROKERAGE SERVICES, INC., MEMBER NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Fifteenth Season, 1995-96 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Robert P. O'Block John E. Cogan, Jr. Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read Julian Cohen Avram J. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Carol Scheifele-Holmes William F. -

Get Lit Classic Poems 2014-2015

GET LIT’S CLASSIC SLAM POEMS & EXCERPTS, 2014-2015 © 2014 Yellow Road Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents All Lovely Things by Conrad Aiken ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Lot’s Wife by Anna Akhmatova ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 Grief Calls Us to the Things of This World by Sherman Alexie .................................................................................................... 9 The Diameter of the Bomb by Yehuda Amichai ............................................................................................................................. 10 Life Doesn’t Frighten Me by Maya Angelou ..................................................................................................................................... 11 I am a Mute Iraqi with a Voice by Anonymous ................................................................................................................................ 13 Siren Song by Margaret Atwood .......................................................................................................................................................... 14 Green Chile by Jimmy Santiago Baca ................................................................................................................................................ -

The Walters Art Museum Year in Review July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014

THE Walters ArT MUSEUM YEAR IN REVIEW JULY 1, 2013–June 30, 2014 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE 50 Walters Women's Committee EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 5 50th Anniversary Gift Donors 52 Recognition Gifts DEPUTY DIRECTORS' REPORTS 7 53 Endowment Gifts and Pledges 54 Named Endowment Funds EXHIBITIONS 13 13 Special Exhibitions VOLUNTEERS 57 14 Focus Exhibitions 57 Corporate Task Force 15 Off-Site Exhibitions 57 Planned Giving Advisory Council 16 Lenders to Walters Exhibitions 57 Walters Enthusiasts Steering Committee 16 Walters Loans to Exhibitions 57 William T. Walters Association 58 The Women's Committee ACQUISITIONS 19 59 Docents 19 Bequests 60 Interns 19 Gifts 60 Volunteers 23 Museum Purchases STAFF 63 STAFF RESEARCH 25 63 Executive Director's Office 25 Publications 63 Art and Program 26 Staff Research and 64 Museum Advancement Professional Activities 64 Administration and Operations DONORS 33 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 67 33 Government 33 Individual and Foundation Donors FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 69 43 Legacy Society 44 Gifts to the Annual Giving Campaign 46 Corporate Supporters 46 Matching Gift Partners 46 Special Project Support 47 Gala 2013 49 Gala 2013 Party 50 Art Blooms 2014 THE Walters ArT MUSEUM: YEAR IN REVIEW 2013–2014 3 Letter froM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR This annual report represents the first full year of my than 69,000 students in the museum, to the increase tenure as the Executive Director of this great Museum. in numbers of objects available to global audiences on What an incredible privilege it has been to be among our Works of Art website. you, a community of people who care deeply about In this report you will notice the reorganization the Walters and who ardently believe that art muse- that I undertook in April 2014 in order to create cross- ums have a role in transforming society.