Constructing the Danube Monarchy: Habsburg State-Building in the Long Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

15 Days 13 Nights Medjugorje, Eastern Europe Pilgrimage

25-09-2018 15 DAYS 13 NIGHTS MEDJUGORJE, EASTERN EUROPE PILGRIMAGE (Vienna, Dubrovnik, Medjugorje, Mostar, Sarajevo, Zagreb, Budapest, Krakow, Wadowice, Czestochowa & Prague Departure dates: 25th May / 15th Jun / 19th Oct 2019 Spiritual Director: TBA (Final Itinerary subject to airlines confirmation) Itinerary: DAY 1: BORNEO OR KUL – DUBAI - ZAGREB (MEAL ON BOARD) • Borneo Pilgrims – Depart KKIA to KLIA and meet main group at Emirate Check in counter. • KL Pilgrims - Assemble 3 hours before at Emirate check in counter • Flight departs after midnight at 1.55am for Zagreb via Dubai (Transit 3hrs 30mins). DAY 2: ZAGREB (L,D) Arrive Zagreb at 12.35 noon. After immigration and baggage clearance, meet and proceed for half day City tour. ❖ Funicular journey to upper town Gornji Grad, view of Zagreb Cathedral, Bloody Bridge. visit the St Mark’s Square which consists of the Parliament Building, Lotrscak Tower, Tkalciceva Street ➢ Cathedral of Assumption - it is the symbol of Zagreb with its two neo-Gothic towers dominating the skyline at 104 and 105 metres. In the Treasury of the Cathedral, above the sacristy, priceless treasures have been stored, including the artefacts from 11th to 19th century. Many great Croats had been buried inside the Cathedral. ➢ St Mark’s Square - St. Mark’s Church that was built in the mid-13th century dominates this most beautiful square of the Upper Town. Many events crucial for Zagreb and entire Croatia took place here and many important edifices and institutions are located in this relatively tight space. The most attractive of all is St. Mark’s Church with its Romanesque naves, Gothic vaults and sanctuary and picturesque tiles on its multi-coloured roof that are arranged in such way that they form historical coats of arms of Zagreb and Croatia. -

Gratuities Gratuities Are Not Included in Your Tour Price and Are at Your Own Discretion

Upon arrival into Budapest, you will be met and privately transferred to your hotel in central Budapest. On the way to the hotel, you will pass by sights of historical significance, including St. Stephen’s Basilica, a cross between Neo-Classical and Renaissance-style architecture completed in the late 19th century and one of Budapest’s noteworthy landmarks. Over the centuries, Budapest flourished as a crossroads where East meets West in the heart of Europe. Ancient cultures, such as the Magyars, the Mongols, and the Turks, have all left an indelible mark on this magical city. Buda and Pest, separated by the Danube River, are characterized by an assortment of monuments, elegant streets, wine taverns, coffee houses, and Turkish baths. Arrival Transfer Four Seasons Gresham Palace This morning, after meeting your driver and guide in the hotel lobby, drive along the Danube to see the imposing hills of Buda and catch a glimpse of the Budapest Royal Palace. If you like, today you can stop at the moving memorial of the Shoes on the Danube Promenade. Located near the parliament, this memorial honors the Jews who fell victim to the fascist militiamen during WWII. Then drive across the lovely 19th-century Chain Bridge to the Budapest Funicular (vertical rail car), which will take you up the side of Buda’s historic Royal Palace, the former Hapsburg palace during the 19th century and rebuilt in the Neo-Classical style after it was destroyed during World War II. Today the castle holds the Hungarian National Gallery, featuring the best of Hungarian art. -

Grand Hotels Around the Kvarner Bay: Seaside Hospitality Between Austria and Hungary Jasenka Gudelj Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia

e-ISSN 2280-8841 MDCCC 1800 Vol. 9 – Luglio 2020 Grand Hotels Around the Kvarner Bay: Seaside Hospitality Between Austria and Hungary Jasenka Gudelj Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia Abstract The hotel architecture around the Kvarner bay represents a specific Austro-Hungarian response to the Riviera phenomenon, made possible by the railway connections to the continental capitals of the Empire with the port of Rijeka. Through a detailed comparison between different investments and realisations, the article explores the ways of dealing with the hotellerie in the coastal area administratively divided between Austria, Hungary and Croatia in the last decades of the 19th century and the years leading to WWI. Keywords Hotel architecture. Kvarner bay. Rijeka. Sušak. Crikvenica. Summary 1 Rijeka and Sušak Between Hungarian Investments and Local Capital. – 2 Opatija/Abbazia: The Corporate Identity of ‘Viennese Brighton’. – 3 Crikvenica: an Archduke in Action. – 4 Conclusion: Architecture of Grand hotels between Politics and Services. The grand hotel, one of the emblematic phenome- tury. The Northern Adriatic participated in these na of the 19th century, is usually referred to as a developments, especially Venice, already an oblig- particularly apt illustration of the changing soci- atory stop of the Ancien-Regime Grand Tour.2 The ety of its time. These hospitality structures reach earliest and the most prominent responses in the the level of lavishness previously reserved to no- Austria-Hungary to the French and Italian riviera ble palaces and become somewhat liberal places stimuli are to be found around the Kvarner bay in of public encounter across space and class.1 The the north-eastern Adriatic, worth looking at in a golden age of both city and leisure hotels in Eu- more detailed comparative perspective. -

What an Almost 500-Year-Old Map Can Tell to a Geoscientist

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Acta Geod. Geoph. Hung., Vol. 44(1), pp. 3–16 (2009) DOI: 10.1556/AGeod.44.2009.1.2 REDISCOVERING THE OLD TREASURES OF CARTOGRAPHY — WHAT AN ALMOST 500-YEAR-OLD MAP CAN TELL TO A GEOSCIENTIST BSzekely´ 1,2 1Christian Doppler Laboratory, Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Vienna University of Technology, Gusshausstr. 27–29, A-1040 Vienna, Austria, e-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Geophysics and Space Science, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, E¨otv¨os University, P´azm´any P. s´et´any 1/C, H-1117 Budapest, Hungary Open Access of this paper is sponsored by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund under the grant No. T47104 OTKA (for online version of this paper see www.akkrt.hu/journals/ageod) Tabula Hungariae (1528), created by Lazarus (Secretarius), is an almost 500 year-old map depicting the whole Pannonian Basin. It has been used for several geographic and regional science studies because of its highly valued information con- text. From geoscientific point of view this information can also be evaluated. In this contribution an attempt is made to analyse in some extent the paleo-hydrogeography presented in the map, reconsidering the approach of previous authors, assuming that the mapmaker did not make large, intolerable errors and the known problems of the cartographic implementation are rather exceptional. According to the map the major lakes had larger extents in the 16th century than today, even a large lake (Lake Becskerek) ceased to exist. -

Master Thesis Bewertung Der Fischbestände Der Gewässer Gurk

Master Thesis im Rahmen des Universitätslehrganges „Geographical Information Science & Systems“ (UNIGIS MSc) am Zentrum für Geoinformatik (Z_GIS) der Paris-Lodron-Universität Salzburg zum Thema Bewertung der Fischbestände der Gewässer Gurk und Glan nach WRRL und Vergleich mit biotischen und abiotischen Faktoren vorgelegt von Michael Schönhuber U1287, UNIGIS MSc Jahrgang 2006 Zur Erlangung des Grades „Master of Science (Geographical Information Science & Systems) – MSc (GIS)“ Gutachter: Ao. Univ. Prof. Dr. Josef Strobl Klagenfurt, den 28.02.2009 Inhaltverzeichnis Danksagung........................................................................................................3 Eigenständigkeitserklärung.................................................................................4 Einleitung ............................................................................................................5 Zielsetzung .........................................................................................................9 Allgemeines zu den Gewässern Gurk und Glan ...............................................10 Methodik ...........................................................................................................15 Ermittlung des Zustandes eines Gewässers................................................15 Biologische Qualitätselemente ....................................................................17 Qualitätselement „Fische“ ......................................................................17 Auswertung der Fischrohdaten -

Saint ADALBERT and Central Europe

POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA AUSTRIA HUNGARY SLO CRO ITALY BiH SERBIA ME BG Saint ADALBERT and Central Europe Patrimonium Sancti Adalberti Collective of Authors Patrimonium Sancti Adalberti Society issued this collection of essays as its first publication in 2021. I/2021 Issuing of the publication was supported by companies: ZVVZ GROUP, a.s. RUDOLF JELÍNEK a.s. PNEUKOM, spol. s r.o. ISBN 978-80-270-9768-5 Saint ADALBERT and Central Europe Issuing of the publication was supported by companies: Collective of Authors: Petr Bahník Jaroslav Bašta Petr Drulák Aleš Dvořák Petr Charvát Stanislav Janský Zdeněk Koudelka Adam Kretschmer Radomír Malý Martin Pecina Igor Volný Zdeněk Žák Introductory Word: Prokop Siostrzonek A word in conclusion: Tomáš Jirsa Editors: Tomáš Kulman, Michal Semín Publisher: Patrimonium Sancti Adalberti, z.s. Markétská 1/28, 169 00 Prague 6 - Břevnov Czech Republic [email protected] www.psazs.cz Cover: Statue of St. Adalbert from the monument of St. Wenceslas on Wenceslas Square in Prague Registration at Ministry of the Culture (Czech Republic): MK ČR E 24182 ISBN 978-80-270-9768-5 4 / Prokop Siostrzonek Introductory word 6 / Petr Bahník Content Pax Christiana of Saint Slavník 14 / Radomír Malý Saint Adalbert – the common patron of Central European nations 19 / Petr Charvát The life and work of Saint Adalbert 23 / Aleš Dvořák Historical development and contradictory concepts of efforts to unite Europe 32 / Petr Drulák A dangerous world and the Central European integration as a necessity 41 / Stanislav Janský Central Europe -

Die Geologischen Verhältnisse Des Gebietes N Feistritz-Pulst Im Glantal, Kärnten

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Austrian Journal of Earth Sciences Jahr/Year: 1962 Band/Volume: 55 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hajek H. Artikel/Article: Die geologischen Verhältnisse des Gebietes N Feistritz-Pulst im Glantal, Kärnten. 1-39 © Österreichische Geologische Gesellschaft/Austria; download unter www.geol-ges.at/ und www.biologiezentrum.at Mitteilungen der Geologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 55. Band 1962 S. 1 - 40, mit 1 Karte, 3 Schliffbildern und 1 Tabelle Die geologischen Verhältnisse des Gebietes N Feistritz-Pulst im Glantal, Kärnten Von H. Hajek *), Eisenerz, Steiermark Mit 1 Karte, 3 Schlifffoildiern und 1 Tabelle Einleitung Die vorliegende Arbeit ist die Zuisammenlassunig des ersten Teiles meiner im Herbst 1959 abgeschlossenen Dissertation. Sie wurde mir von Prof Dr. K. METZ übertragen, und es ist mir ein besonderes Anliegen, ihm an dieser Stelle für seine Anteilnahme und für seine Unterstützung auf richtig zu danken. Bearbeitet wurde das Gebiet W dler Predlstöriung W GauerstaU, W. St. Veit a. d. Glan .Die Nordigrenze verläuft über denl Schneebauer- berg am Kamm nach Hoch-St. Paul und zum Hocheek im W. Die Süd grenze bildet die Glan. Die besonders auf den Hochflächen sehr ungünstigen Aufschlußverhält nisse zwangen zu einem engen BegeihuingHnetz. Günstige Aufschlüsse sind nur im Bereich junger Störungen zu finden», denen die tiefengeschnittenen Bäche folgen. Die Kartierung wurdle vom weniger metamorphen Gebiet im S aus gehend nach N vorgetragen. Dabei koninten die Metiamorphosevearhältnisse verfolgt und im Bereich St. Paul—Hocheck interessante tektondsche Be obachtungen festgestellt werten. Die aufgesammelten HaindBtück© und die dazugehörigen Dünnschliffe befinden sich in der Sammlung des Geol.-Pal. -

Step 2025 Urban Development Plan Vienna

STEP 2025 URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VIENNA TRUE URBAN SPIRIT FOREWORD STEP 2025 Cities mean change, a constant willingness to face new develop- ments and to be open to innovative solutions. Yet urban planning also means to assume responsibility for coming generations, for the city of the future. At the moment, Vienna is one of the most rapidly growing metropolises in the German-speaking region, and we view this trend as an opportunity. More inhabitants in a city not only entail new challenges, but also greater creativity, more ideas, heightened development potentials. This enhances the importance of Vienna and its region in Central Europe and thus contributes to safeguarding the future of our city. In this context, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 is an instrument that offers timely answers to the questions of our present. The document does not contain concrete indications of what projects will be built, and where, but offers up a vision of a future Vienna. Seen against the background of the city’s commit- ment to participatory urban development and urban planning, STEP 2025 has been formulated in a broad-based and intensive process of dialogue with politicians and administrators, scientists and business circles, citizens and interest groups. The objective is a city where people live because they enjoy it – not because they have to. In the spirit of Smart City Wien, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 suggests foresighted, intelli- gent solutions for the future-oriented further development of our city. Michael Häupl Mayor Maria Vassilakou Deputy Mayor and Executive City Councillor for Urban Planning, Traffic &Transport, Climate Protection, Energy and Public Participation FOREWORD STEP 2025 In order to allow for high-quality urban development and to con- solidate Vienna’s position in the regional and international context, it is essential to formulate clearcut planning goals and to regu- larly evaluate the guidelines and strategies of the city. -

H.U.G.E.S. a Visit to Budapest (25Th September -30Th September

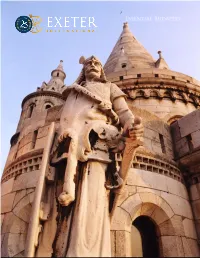

H.U.G.E.S. A Visit to Budapest (25th September -30th September) 26th September, Monday The first encounter between our students and the Comenius partners took place in the hotel lobby, from where they were escorted by two volunteer students (early birds) to school. On the way to school they were given a taste of the city by the same two students, Réka Mándoki and Eszter Lévai, who introduced some of the famous buildings and let the enthusiastic teachers take several photos of them. In the morning there was a reception in school. The teachers met the head mistress, Ms Veronika Hámori, and the deputy head, Ms Katalin Szabó, who showed them around in the school building. Then, the teachers visited two classroom lessons, one of them being an English lesson where they enchanted our students with their introductory presentations describing the country they come from. The second lesson was an advanced Chemistry class, in which our guests were involved in carrying out experiments. Although they blew and blew, they didn’t blow up the school building. In the afternoon, together with the students involved in the project (8.d), we went on a sightseeing tour organised by the students themselves. A report on the event by a pupil, Viktória Bíró 8.d At the end of September my English group took a trip to the heart of Budapest. We were there with teachers from different countries in Europe. We walked along Danube Promenade, crossed Chain Bridge and went up to Fishermen’s Bastion. Fortunately, the weather was sunny and warm. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

56 Stories Desire for Freedom and the Uncommon Courage with Which They Tried to Attain It in 56 Stories 1956

For those who bore witness to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, it had a significant and lasting influence on their lives. The stories in this book tell of their universal 56 Stories desire for freedom and the uncommon courage with which they tried to attain it in 56 Stories 1956. Fifty years after the Revolution, the Hungar- ian American Coalition and Lauer Learning 56 Stories collected these inspiring memoirs from 1956 participants through the Freedom- Fighter56.com oral history website. The eyewitness accounts of this amazing mod- Edith K. Lauer ern-day David vs. Goliath struggle provide Edith Lauer serves as Chair Emerita of the Hun- a special Hungarian-American perspective garian American Coalition, the organization she and pass on the very spirit of the Revolu- helped found in 1991. She led the Coalition’s “56 Stories” is a fascinating collection of testimonies of heroism, efforts to promote NATO expansion, and has incredible courage and sacrifice made by Hungarians who later tion of 1956 to future generations. been a strong advocate for maintaining Hun- became Americans. On the 50th anniversary we must remem- “56 Stories” contains 56 personal testimo- garian education and culture as well as the hu- ber the historical significance of the 1956 Revolution that ex- nials from ’56-ers, nine stories from rela- man rights of 2.5 million Hungarians who live posed the brutality and inhumanity of the Soviets, and led, in due tives of ’56-ers, and a collection of archival in historic national communities in countries course, to freedom for Hungary and an untold number of others.