The King's Gambit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

The Double Queen's Gambit

Alexey Bezgodov The Double Queen’s Gambit A Surprise Weapon for Black New In Chess 2015 Contents Explanation of Symbols .......................................... 6 Introduction .................................................. 7 Part I – White avoids the main variations . 11 Chapter 1 White accepts the gambit ........................14 Chapter 2 The white bishop comes out ......................17 Chapter 3 Transposing into the Alapin Variation of the Sicilian.....24 Chapter 4 Transposition into the Exchange Variation of the Slav Defence 27 Chapter 5 Transposition into the Panov Attack .................37 Part II – Who is tricking whom? 3 .♘f3 . 49. Chapter 6 The rare symmetrical endgame ....................51 Chapter 7 The mysterious black queen check .................56 Chapter 8 The centralised knights system ....................66 Part III – The queenless DQG: 3 .♘f3 cxd4 4 .cxd5 ♘f6 5 .♕xd4 ♕xd5 6 .♘c3 ♕xd4 7 .♘xd4 . 97 Chapter 9 7...a6 – Taking control of the square b5.............100 Chapter 10 7…♗d7 – The bishop-retention system ............129 Chapter 11 7...e5 – The move of the future? ..................143 Part IV – The Gorbatov Gambit and the imaginary Semi-Tarrasch: 3 .♘c3 . 155 Chapter 12 A fascinating gambit ...........................157 Chapter 13 The classical 3...♘f6 ...........................163 Part V – The Deferred Capture Variation: 3 .cxd5 ♘f6 . 177 Chapter 14 White takes on c5 .............................179 Chapter 15 The strong 4.e4...............................187 Chapter 16 An Attempt at Revival ..........................193 Part VI – The main variation: 3 .cxd5 ♕xd5 . 205 Chapter 17 Early divergences..............................208 Chapter 18 The Queen Retreats 5...♕d7/5...♕d8 .............217 Chapter 19 Minor white moves after 6...♘f6..................223 Chapter 20 The fianchetto 7.g3 ............................233 Part VII – Retro-Training . 247 Postscript...............................................278 Bibliography................................................ -

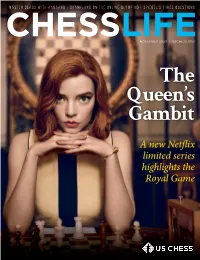

The Queen's Gambit

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: -

See Contents

Technical Editor: IM Sergey Soloviov Translation by: GM Evgeny Ermenkov The publishers would like to thank Phil Adams for advice regarding the English translation. Cover design by: Kalojan Nachev Copyright © Alexei Kornev 2013 Printed in Bulgaria by “Chess Stars” Ltd. - Sofia ISBN13: 978 954 8782 93-7 Alexei Kornev A Practical White Repertoire with 1.d4 and 2.c4 Volume 1: The Complete Queen’s Gambit Chess Stars Bibliography Books A Strategic Chess Opening Repertoire for White by Watson, Gambit 2012 Playing 1.d4. The Queen’s Gambit by Schandorff, Quality Chess 2012 The Complete Slav Book 1 by Sakaev, St Peterburg 2012 The French Defence Reloaded by Vitiugov, Chess Stars 2012 The Meran & Anti-Meran Variations by Dreev, Chess Stars 2011 The Tarrasch Defence, by Aagaard and Ntrilis, Quality Chess 2011 The Queen’s Gambit Accepted by Raetsky and Chetverik, Moscow 2009 Grandmaster Repertoire 1.d4, volume one, by Avrukh, Quality Chess 2008 The Queens Gambit Accepted by Sakaev and Semkov, Chess Stars 2008 Electronic/Periodicals 64-Chess Review (Moscow) Chess Informant New in chess Yearbook Correspondence Database 2013 Mega Database 2013 4 Contents Preface . 7 Part 1. Black avoids the main lines 1.d4 d5 2.c4 1 2...c5 . 10 2 2...Bf5 . 16 3 The Chigorin Defence 2...Nc6 . 22 4 The Albin Counter-gambit 2...e5 . 36 Part 2. The Queen’s Gambit Accepted 1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.e3 5 3...c5; 3...e5 . 53 6 3...Nf6 4.Bxc4 e6 . 63 7 3...e6 4.Bxc4 Nf6 5.Nf3 c5 6.0-0 a6 . -

4 the Fianchetto Variation

Contents Symbols 4 Bibliography 5 Introduction 6 1 The Reversed Sicilian: Introduction 7 2 The Reversed Dragon (Main Lines) 29 3 The Closed Variation 43 4 The Fianchetto Variation (King’s Indian Approach by Black) 58 5 The Three Knights 76 6 The Four Knights without 4 g3 92 7 The Four Knights with 4 g3 134 8 Systems with ...f5 167 9 Systems with 2...d6 or 2...Íb4 207 10 Early Deviations 237 Index of Variations 254 THE FIANCHETTO VARIATION 4 The Fianchetto Variation (King’s Indian Approach by Black) The lines covered in this chapter are become problematic if White is able to hugely popular among players who get his b-pawn rolling, as the contact employ the King’s Indian with the with Black’s pawns is instantaneous. black pieces. Black often hopes that White will ‘cooperate’ by playing d4 -+-+-+-+ and thereby enter the Fianchetto King’s +pz-+p+p Indian. If this is not to White’s taste, he can continue along the lines given -+-z-+p+ below. +P+-z-+- The lines are at times quite compli- -+P+-+-+ cated, but with careful study from ei- +-+P+-Z- ther side, both White and Black can play for the full point. -+-+PZ-Z +-+-+-+- Typical Pawn Structures -+-+-+-+ Here, we have already had an initial +p+-+p+p confrontation, which resulted in the a-pawns leaving the board. White has -+pz-+p+ a huge space advantage on the queen- z-+-z-+- side, while Black initially does not -+P+-+-+ have much on the kingside, but poten- +-+P+-Z- tially he can gain a similar advantage PZ-+PZ-Z by playing ...h6, ...g5, and ...f4. -

Four Opening Systems to Start with a Repertoire for Young Players from 8 to 80

Four opening systems to start with A repertoire for young players from 8 to 80. cuuuuuuuuC cuuuuuuuuC (rhb1kgn4} (RHBIQGN$} 70p0pDp0p} 7)P)w)P)P} 6wDwDwDwD} 6wDwDwDwD} 5DwDw0wDw} 5dwDPDwDw} &wDwDPDwD} &wDwDwdwD} 3DwDwDwDw} 3dwDpDwDw} 2P)P)w)P)} 2p0pdp0p0} %$NGQIBHR} %4ngk1bhr} v,./9EFJMV v,./9EFJMV cuuuuuuuuC (RHBIQGw$} 7)P)Pdw)P} &wDw)wDwD} 6wDwDwHwD} 3dwHBDNDw} 5dwDw)PDw} 2P)wDw)P)} &wDwDp0wD} %$wGQ$wIw} 3dwDpDwDw} v,./9EFJMV 2p0pdwdp0} %4ngk1bhr} vMJFE9/.,V A public domain e-book. [Summary Version]. Dr. David Regis. Exeter Chess Club. - 1 - - 2 - Contents. Introduction................................................................................................... 4 PLAYING WHITE WITH 1. E4 E5 ..................................................................................... 6 Scotch Gambit................................................................................................ 8 Italian Game (Giuoco Piano)........................................................................10 Two Knights' Defence ...................................................................................12 Evans' Gambit...............................................................................................14 Petroff Defence.............................................................................................16 Latvian Gambit..............................................................................................18 Elephant Gambit 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d5.............................................................19 Philidor -

Double Fianchetto – the Modern Chess Lifestyle

DOUBLE-FIANCHETTO THE MODERN CHESS LIFESTYLE by Daniel Hausrath www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniel Vanheirzeele Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Iwan Kerkhof Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing Double-Fianchetto — the Modern Chess Lifestyle Copyright © 2020 Daniel Hausrath All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-075-4 D/2020/13730/3 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 PREFACE 7 PART 1. DOUBLE FIANCHETTO WITH WHITE 9 Chapter 1. Double fi anchetto against the King’s Indian and Grünfeld 11 Chapter 2. Double fi anchetto structures against the Dutch 59 Chapter 3. Double fi anchetto against the Queen’s Gambit and Tarrasch 77 Chapter 4. Diff erent move orders to reach the Double Fianchetto 97 Chapter 5. Diff erent resulting positions from the Double Fianchetto and theoretically-important nuances 115 PART 2. DOUBLE FIANCHETTO WITH BLACK 143 Chapter 1. Double fi anchetto in the Accelerated Dragon 145 Chapter 2. Double fi anchetto in the Caro Kann 153 Chapter 3. Double fi anchetto in the Modern 163 Chapter 4. Double fi anchetto in the “Hippo” 187 Chapter 5. Double fi anchetto against 1.d4 205 Chapter 6. Double fi anchetto in the Fischer System 231 Chapter 7. -

FIDE Online General Assembly 6 December 2020

FIDE Online General Assembly 6 December 2020 MINUTES 1. FIDE President’s address FIDE President welcomed all to the first ever meeting of the Online General Assembly and said that we are learning to work under new conditions and it is not an easy exercise. He proposed not to have formal scrutineers since the system does the count automatically and everyone receives the list with all the comprehensive data after the end of General Assembly; the only secret vote is for Olympiad 2024. The General Assembly approved. Dear Delegates of FIDE Online General Assembly, Dear chess friends, It is a privilege to share with you the results of our work, to summarize what has been achieved over the last two years, and to plan together for the future. My manifesto in 2018 included several promises, and I can proudly say that our dedicated team has managed to deliver - even during the difficult time of the pandemic. Our development program provided support to projects in more than 100 countries, and FIDE will keep providing this help since we know how important it is for national federations. Last year we allocated over 2 mln Euro for these purposes, this year we budgeted 1 mln Euro - due to reduced activity caused by the pandemic - but we are ready to get back to a full-scale support once the situation is normalized. Not only we cared to deliver funds to the federations, we ensured constant technical assistance and communication in such a way that many federations could feel that FIDE is always there for them. -

The Queen's Gambit

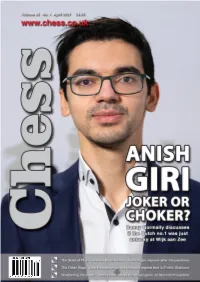

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

Introduction

Introduction One day, at the end of a group lesson on basic rook endgame positions that I had just given at my club, one of my students, Hocine, aged about ten, came up to ask me: «But what is the point of knowing the Lucena or Philidor positions? I never get that far. Often I lose before the ending because I didn’t know the opening. Teach us the Sicilian Defence instead, it will be more useful». Of course, I tried to make him understand that if he lost it was not always, or even often, because of his short comings in the opening. I also explained to him that learning the endgames was essential to progress in the other phases of the game, and that the positions of Philidor or Lucena (to name but these two) should be part of the basic knowledge of any chess player, in much the same way that a musician must inevitably study the works of Mozart and Beethoven, sooner or later. However, I came to realize that I had great difficulty in making him see reason. Meanwhile Nicolas, another of my ten-year-old students, regularly arrives at classes with a whole bunch of new names of openings that he gleaned here and there on the internet, and that he proudly displays to his club mates. They remain amazed by all these baroque-sounding opening names, and they have a deep respect for his encyclopaedic knowledge. For my part, I try to behave like a teacher by explaining to Nicolas that his intellectual curiosity is commendable, but that knowledge of the Durkin Attack, the Elephant Gambit or the Mexican Defence, as exciting as they might be, has a rather limited practical interest at the board. -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 6 Dedication 6 Acknowledgements 6 Bibliography 7 Introduction 10 1 Réti: Open and Closed Variations 12 The 2...d4 Advance 13 The Open Réti 20 The Closed Réti 23 The Réti Benoni 27 The ...b6 Fianchetto 29 2 Réti: Slav Variations 34 The System with ...Íg4 35 The System with ...Íf5 39 The Gambit Accepted 42 The Double Fianchetto System 46 Capablanca Variation with 4...Íg4 48 The New York System 51 3 Modern Kingside Fianchetto 56 The Modern Defence 57 Tiger’s Modern 63 Modern Defence with an Early ...c6 68 Classical Set-Up 80 Other White Formations 84 Averbakh Variation 90 4 Modern Queenside Fianchetto 94 Owen Defence 94 English Defence 106 Larsen’s Opening: 1 b3 125 5 Gambits 133 Primitive Gambits 134 4 MASTERING THE CHESS OPENINGS Danish and Göring Gambits 134 Milner-Barry Gambit 145 Morra Gambit 149 Blackmar-Diemer Gambit 157 Other Primitive Gambits 159 Positional Gambits 160 b4 Gambits 161 g4 Gambits in the Dutch Defence 161 ...b5 Gambits in the Nimzo-Indian Defence 163 Gambits in the Réti Opening 165 The Evans Gambit 166 Positional Gambits of Centre Pawns 170 The Ultra-Positional Benko Gambit 172 6 f-Pawns and Reversed Openings 182 Dutch Defence/Bird Opening 183 Leningrad Dutch 185 Bird Opening 191 Classical Dutch 201 Stonewall Dutch 208 King’s Indian Attack 212 Reversing Double e-Pawn Openings 221 7 Symmetry and Its Descendants 229 Petroff Defence 229 Four Knights Game 236 Symmetry in the English Opening 243 English Double Fianchetto Variation 244 8 Irregular Openings and Initial Moves 249 The Appeal of the