Creating a Model Village Center: Strategies for Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mass-Ala 2017Events

MASS•ALA MASSACHUSETTS ASSISTED LIVING ASSOCIATION 465 Waverley Oaks Road , Suite 300 Waltham, MA 02452 Phone: 781-622-5999 Fax: 781-622-5979 www.mass-ala.org Social icon Circle Only use blue and/or white. For more details check out our Brand Guidelines. 5-year In a world of choices... rate lock! New Horizons might be the right one for you and your family! Connecting People Choosing the most appropriate independent or assisted living community is never easy. With so many options, the decision can be daunting. to Possibilities With over 20 years of experience, Benchmark Senior Living Unlike most every other retirement community in New England, New believes possibilities start with authentic connections, Horizons guarantees all residents NO INCREASE in its regular monthly fee and it’s those connections that transform lives. for at least five years! This fee includes lodging, housekeeping, meals, water, Interested in connecting with one of our Massachusetts heat, air conditioning, parking, maintenance, cable, etc. communities, please contact us. 888.335.6548 We welcome a visit at your leisure, and encourage BenchmarkSeniorLiving.com you to enjoy the wealth of information, including unsolicited testimonials and colorful photographs | A turning point in senior living Independent Living Assisted Living on our Website, CummingsFoundation.org. 400 Hemenway Street, Memory Care | Skilled Nursing See why so many wonderful seniors choose New Marlborough (Sudbury), MA Horizons as their home. 508-460-5200 One of New England’s largest and finest assisted living communities, located just off US 20 near Routes 9 and I-495. Not-for-profit • State Certified • Independent & Assisted Living Assisted Living in Massachusetts 2018 RESOURCE GUIDE TWENTY-THIRD EDITION EDUCATE. -

Village Residential District Model Ordinance

Montgomery County, Pennsylvania Creating a Village Community village residential district Montgomery County Board of Commissioners Josh Shapiro, Chair Leslie S. Richards, Vice Chair Bruce L. Castor, Jr., Commissioner Montgomery County Planning Commission Board P. Gregory Shelly, Chair Scott Exley, Vice Chair Dulcie F. Flaharty Henry P. Jacquelin Pasquale N. Mascaro Roy Rodriguez, Jr. Charles J. Tornetta V. Scott Zelov Steven L. Nelson, Director village residential district Creating a Village Community Prepared by the Montgomery County Planning Commission 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................1 The Village Residential Development Concept What is the Village Residential District? .................................................................................5 Why Have a Village Residential District?................................................................................6 What Will a Village Residential Development Look Like? ......................................................8 Local Examples ......................................................................................................................9 Planning for Village Residential Development Where Should the Village Residential District Be Used?......................................................13 Suitable Location - Infill Within a Village...............................................................................14 Suitable Location -

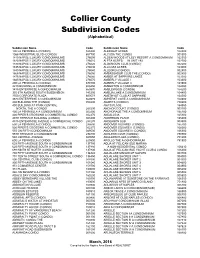

Collier County Subdivision Code List

Collier County Subdivision Codes (Alphabetical) Subdivision Name Code Subdivision Name Code 100 LA PENINSULA (CONDO) 528400 ALBRIGHT ACRES 162400 1068 INDUSTRIAL BLVD (CONDO) 657700 ALCOSA THE CONDO 001900 1810 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276000 ALDEN WOODS AT LELY RESORT A CONDOMINIUM 162550 1820 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276010 ALETA ACRES IN UNIT 193 162700 1830 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276020 ALGONQUIN CLUB (CONDO) 002200 1835 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276030 ALLCOAT ACRES 163000 1840 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276040 ALLEGRO (CONDO) 002500 1865 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276050 AMBASSADOR CLUB THE (CONDO) 002800 1875 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276060 AMBER AT SAPPHIRE LAKES 163300 1885 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276070 AMBERLY VILLAGE I 163600 200 LA PENINSULA (CONDO) 677800 AMBERLY VILLAGE II 163900 2210 BUILDING A CONDOMINIUM 653450 AMBERTON A CONDOMINIUM 164050 3435 ENTERPRISE A CONDOMINIUM 660570 AMBLEWOOD (CONDO) 164200 350 6TH AVENUE SOUTH SUBDIVISION 145250 AMELIA LAKE A CONDOMINIUM 164400 3500 CORPORATE PLAZA 660573 AMETHYST CLUB AT SAPPHIRE 164500 3573 ENTERPRISE A CONDOMINIUM 660575 AMHERST COVE A CONDOMINIUM 164800 400 BUILDING THE (CONDO) 050200 ANAHITA (CONDO) 750600 400 BUILDING AT PARK CENTRAL ANA'S PLACE 164950 NORTH, THE A CONDO 283230 ANCHOR COURT (CONDO) 003100 400 LA PENINSULA A CONDOMINIUM 302200 ANCHORAGE THE A CONDOMINIUM 165100 400 PIPER'S CROSSING A COMMERCIAL CONDO 302270 ANDALUCIA 165300 40TH TERRACE BUILDING (CONDO) 303400 ANDERSON PLACE 165400 4375 ENTERPRISE AVENUE A COMMERCIAL CONDO 283270 ANDERSON -

Opticianry Employers - USA

www.Jobcorpsbook.org - Opticianry Employers - USA Company Business Street City State Zip Phone Fax Web Page Anchorage Opticians 600 E Northern Lights Boulevard, # 175 Anchorage AK 99503 (907) 277-8431 (907) 277-8724 LensCrafters - Anchorage Fifth Avenue Mall 320 West Fifth Avenue Ste, #174 Anchorage AK 99501 (907) 272-1102 (907) 272-1104 LensCrafters - Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard, #3-138 Anchorage AK 99515 (907) 344-5366 (907) 344-6607 http://www.lenscrafters.com LensCrafters - Sears Mall 600 E Northern Lights Boulevard Anchorage AK 99503 (907) 258-6920 (907) 278-7325 http://www.lenscrafters.com Sears Optical - Sears Mall 700 E Northern Lght Anchorage AK 99503 (907) 272-1622 Vista Optical Centers 12001 Business Boulevard Eagle River AK 99577 (907) 694-4743 Sears Optical - Fairbanks (Airport Way) 3115 Airportway Fairbanks AK 99709 (907) 474-4480 http://www.searsoptical.com Wal-Mart Vision Center 537 Johansen Expressway Fairbanks AK 99701 (907) 451-9938 Optical Shoppe 1501 E Parks Hy Wasilla AK 99654 (907) 357-1455 Sears Optical - Wasilla 1000 Seward Meridian Wasilla AK 99654 (907) 357-7620 Wal-Mart Vision Center 2643 Highway 280 West Alexander City AL 35010 (256) 234-3962 Wal-Mart Vision Center 973 Gilbert Ferry Road Southeast Attalla AL 35954 (256) 538-7902 Beckum Opticians 1805 Lakeside Circle Auburn AL 36830 (334) 466-0453 Wal-Mart Vision Center 750 Academy Drive Bessemer AL 35022 (205) 424-5810 Jim Clay Optician 1705 10th Avenue South Birmingham AL 35205 (205) 933-8615 John Sasser Opticians 1009 Montgomery Highway, # 101 -

Lepea: That Model Village in Samoa

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 30, Open Papers presented to the 30th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand held on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, July 2-5, 2013. http://www.griffith.edu.au/conference/sahanz-2013/ Anne Milbank, “Lepea: That Model Village in Samoa” in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 30, Open, edited by Alexandra Brown and Andrew Leach (Gold Coast, Qld: SAHANZ, 2013), vol. 2, p 823-836. ISBN-10: 0-9876055-0-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9876055-0-4 Lepea That Model Village in Samoa Anne Milbank University of Auckland Nearly one hundred years ago Samoa was invaded by New Zealand—the first territory taken by the Allied Forces from the Germans who had occupied the western islands since 1899. The New Zealand Administration instigated following the First World War, a programme of model villages, but only two were completed. The most well known is Lepea. This paper investigates the social and political influences that brought about the design and subsequent re-modelling of the village that is now considered by the general public to be an outstanding example of Samoan architecture. But how did this imposed village type become iconic? What is currently regarded as an exemplar of the “traditional Samoan village” has another side to it, another story. Polynesians have a different concept of time, place and value to that of the European colonisers. It can be found in the notion of va, which is a relational world distinct from the modernist material world.1 Relationships towards people and the land 1. -

Lakewood Village NYMS Technical Assistance Grant

MIXED-USE BUILDING REUSE ANALYSIS & CHAUTAUQUA AVENUE PLAN MIXED-USE BUILDING REUSE ANALYSIS & CHAUTAUQUA AVENUE PLAN Prepared for: Village of Lakewood Cara Birrittieri, Mayor Prepared by: LaBella Associates 300 Pearl Street Buffalo, NY 14202 Developed with funding assistance from Housing Trust Fund Corporation and NYS Homes and Community Renewal. Document is property of Housing Trust Fund Corporation and the Village of Lakewood. SHARS ID# 20180022 CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................... i List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................ iii List of Charts.......................................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ......................................................................................................................................... iii List of Appendices ................................................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Historic Setting -

Silicon Valley Imperialists Create New Model Villages As Smart Cities in Their Own Image

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity Article Silicon Valley Imperialists Create New Model Villages as Smart Cities in Their Own Image Philip Cooke Mohn Center for Innovation & Regional Development, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, 5020 Bergen, Norway; cookepn@cardiff.ac.uk Received: 13 March 2020; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 8 April 2020 Abstract: In her study of ‘Surveillance Capitalism’, Shoshana Zuboff cites Google’s parent firm Alphabet’s legal customer-purchase agreement for the parent firm’s Nest thermostats. These impose ‘oppressive privacy and security consequences’ requiring sensitive information to be shared through ‘Internet-of-Things’ (IoT) networks with other domestic and external devices, unnamed functionaries and various third parties. This is for data harvesting, analytics, processing, manipulation and transformation through digital re-sale to the same and other consumers in the form of unwanted, targeted advertising. The point of this identity ‘rendition’ is to massively augment corporate profits. It is but a short step from trapping the unwitting consumer in a ‘smart home’ to planning a similarly mediated ‘smart city’ aimed at further massively augmenting corporate profits. This is happening, as founders of digital media from Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon and Tesla either commission or become beneficiaries of ‘smart city’ planning. However, there is evidence that such imperiousness is increasingly countered by emerging democratic critique of these new ‘model villages’ or ‘company towns’. Keywords: digital innovations; company towns; smart cities; surveillance capitalism 1. Introduction In recent years, such has been the rapid and successful growth of their corporate profits that Facebook, Amazon, Google, Alphabet and Microsoft (FAGAMi) firms specialising in the design or exploitation of identity theft, big data analytics and automated social media advertising that they have had to create new digital accumulation opportunities. -

Aging in Place and Community: Housing Assistance and Other Services for Seniors in San Francisco

AGING IN PLACE AND COMMUNITY: HOUSING ASSISTANCE AND OTHER SERVICES FOR SENIORS IN SAN FRANCISCO Prepared for the Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco by the Budget and Legislative Analyst OCTOBER, 2010 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AGING IN PLACE AND COMMUNITY: HOUSING ASSISTANCE AND OTHER SERVICES FOR SENIORS IN SAN FRANCISCO Overview San Francisco’s high concentration of seniors, defined by the US Census as adults ages 60 and older, represents a culturally and economically diverse population that is anticipated to increase in coming years. In contrast with many California communities where most residences are newer single family homes, in San Francisco, the majority of seniors reside in older, multi-level apartments and houses that are not likely to meet their safety and accessibility needs, according to the San Francisco Human Services Agency’s Department of Aging and Adult Services (DAAS). Senior advocates suggest that subsidizing independent living for many seniors in their existing residences could be less costly than alternatives such as subsidizing new residential development or residency in assisted living facilities, which typically provide 24-hour supervision. Senior advocates also point out that increasing safety in existing residences can help prevent avoidable falls that result in insurance and medical costs. The Board of Supervisors directed the Budget and Legislative Analyst, by motion, to conduct a review of practices and resources that might enable aging adults in the City and County of San Francisco to -

A Model Village of Homes, and Other Papers

lODEL- VILLAGE » •AND-OT ?J5 !/ii sm ; OLTON LIBRARY OF THE University of California. GIFT OF Class ( a A MODEL VILLAGE OF HOMES AND OTHER PAPERS £ &./3o&<ttt^ ill ayor of East Cleveland, Ohio. i8gg - igoi A MODEL VILLAGE OF HOMES AND OTHER PAPERS By Charles E. Bolton, M. A. v of THE UNIVERSITY Boston: L. C. PAGE & COMPANY, Publishers. Mdcccci 4 «, l Copyright^ igoi By L. C. Page & Company (incorporated) All rights reserved ffiolomal $«0g Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co. Boston, Mass., U.S.A. TO MY GRANDCHILDREN Stanfoooo Itnofoleg Bolton AND (Sttoftteg 33olton 1 07452 PREFACE. I am prompted to send out in book form these several papers, some of which have appeared in the press, with the hope that they may be helpful to others. My wish for the volume is expressed in the words " I to this but once of another, expect pass way ; if, therefore, there be any kindness I can show, or any good thing I can do to my fellow human beings, let me do it now, let me not defer or neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again." Could I have choice of my last word I would place Helpfulness upon the archway of the sky in golden letters large enough to reach from the rising to the setting sun. CONTENTS. PAGB A Model Village of Homes n An English Half -holiday 35 Stage -coaching in England 47 Coffee-houses in Great Britain .... 57 The Sunday-school Centenary, London . 69 The Sunday-school Centenary, London, Con- eluded ........ -

New Gourna Village Conservation and Communıty New Gourna Village: Conservation and Communıty

New Gourna Village Conservation and Communıty New Gourna Village: Conservation and Communıty March 2011 Acknowledgements This assessment was undertaken by World Monuments Fund (WMF) with the support of the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Conserve our Heritage, and in collaboration with the UNESCO World Heritage Centre and the Luxor Governorate of Egypt. The WMF Project Team that carried out the survey and compiled the assessment report included Erica Avrami (WMF Project Manager); Jeff Allen, Gina Haney, Heba Hosny, Eta’ El Hosseiny, and Sarah Badea (all of Community Consortium); and William Raynolds (WMF Consultant). An accompanying film was produced by WMF in collaboration with Community Consortium, directed by Oliver Wilkins and with interviews and translations by Mostafa Naguib. The film, Hassan Fathy’s New Gourna Village: Past, Present and Future, is available at http://www.wmf.org/project/new-gourna-village The UNESCO physical survey team (Mahmoud Qutb, Nevine George, Heba Hosny, and Dalia Magdy) kindly provided the base plan used in this report. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture kindly provided historic images for the assessment and the film. Photography for the report was by Community Consortium, with additional images provided by Mostafa Naguib, Erica Avrami/WMF, and Hubert Guillaud/CRAterre-ENSAG. Graphic design of this report was by Ken Feisel, WMF Art Director. Editorial assistance was provided by Maria Golia. Special thanks go to the residents of New Gourna, who opened their homes to the assessment team and shared their stories. Their interest and cooperation are a testament to Hassan Fathy’s vision for a thriving community and to the shared hope for its future. -

The Land of One Thousand Villages; Examining Rural Resettlement Planning As a Driver for Poverty Reduction in Post-Conflict Rwanda

THE LAND OF ONE THOUSAND VILLAGES; EXAMINING RURAL RESETTLEMENT PLANNING AS A DRIVER FOR POVERTY REDUCTION IN POST-CONFLICT RWANDA. A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning By Tara Heidger March 20, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Kian Tajbakhsh Reader: Dr. Andrea Rizvi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my husband, Chris, who has consistently supported my research and travel whims without complaint. Image of Rwanda landscape taken by Chris Heidger in December 2017. 1 MAP OF RWANDA’S DISTRICTS 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND DEFINITIONS MDG Millennium Development Goals IDP Integrated Development Model Village Umuganda Traditional practice in Rwanda; ‘coming together in common purpose to achieve an outcome’ Imihigo Traditional practice in Rwanda; translates to ‘vow to deliver’ Ubudehe Traditional practice in Rwanda; translates to ‘collective action and mutual support’ Girinka Traditional practice in Rwanda; translates to ‘may you have a cow’ MINALOC Ministry of Local Government MININFRA Ministry of Infrastructure RHA Rwanda Housing Authority Umudugudu Village (singular); the lowest level of government, often used interchangeably as the Rural Resettlement Program Imidugudu Village (plural); the lowest level of government, often used interchangeably as the plural form of the Rural Resettlement Program RPF Rwanda Patriotic Front; current political party; party of President Paul Kagame AOU African Organization for Unity Old Case Refugees who -

Model Villages Kindle

MODEL VILLAGES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Dunn | 64 pages | 01 Feb 2018 | Amberley Publishing | 9781445669144 | English | Chalford, United Kingdom Model Villages PDF Book Things You'll Need. Watch a video about the Beacon Hill village on SeniorPlanet. Decide on a general scale for your model village. The Cave of Swimmers. In an age of Netflix, Fortnite and artificial intelligence, we may regard it as remarkable that such a thing has not only endured, but thrived and even expanded. So landowners had these cottages demolished and the people relocated to a new landscape creating the first model village. Hobby shops sell miniature trees and other plants, stop lights and road signs, that can be included in your town scene. This site uses cookies to improve your browsing experience. But Gerhard Dauscher, the model-maker employed to lead construction, says there are wider aims too, not least the pursuit of miniature beauty. Is there a gift shop at the Model Village? Loved it x. These days Swissminiatur struggles to be the most popular tourist attraction even in the region of Lake Lugano, but its models are both quaint and instructive, and, in their earnestness and number, unique. By Linda Abbit Monday, October 30 10 Comments Share This: We all want to be independent and in control of our lives for as long as possible—preferably until the day we die. An early survey found that the railway itself would mostly attract men, but that women would be more attracted by the exacting detail of the landscapes. There are buildings to see in 25 cities across five continents.