NOBLE WORKERS and UGLY OERL.ORDS Class and Politics in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humber River Heritage Bridge Inventory

CROSSINGTHE H UMBER T HE HE 2011 Heritage H UMBER UMBER Canada Foundation NATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT R AWARD WINNER IVER IVER for Volunteer Contribution HERIT A GE B RIDGE RIDGE I NVENTORY July 2011 CROSSING THE HUMBER THE HUMBER RIVER HERITAGE BRIDGE INVENTORY www.trca.on.ca Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Humber Watershed Alliance, Heritage Subcommittee Newly Released, July 2011 Fold Here PREAMBLE In 2008, I was introduced to the Humber River Heritage Bridge Inventory to provide advice on one of the identified heritage bridges, slated for de-designation and subsequent demolition. Having recently recommended to the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering that they increase their activities in heritage bridge conservation, I was happy to participate in this inventory project as such initiatives highlight the significant and often overlooked relationship between engineering advancements and our cultural heritage. Over time the widespread loss of heritage bridges has occurred for a variety of reasons: deterioration, changes in highway requirements, or damage by storms like Hurricane Hazel. Today, however, with increasing attention towards cultural heritage, creative solutions are being explored for preserving heritage bridges. Protecting, conserving and celebrating our heritage bridges contributes to not only a greater understanding of the development of approaches to modern day engineering but also marks our progress as a nation, from early settlement to today’s modern and progressive communities. Roger Dorton, C.M., Ph.D., P.Eng. 1 -

“Eyes Wide Open”: EW Backus and the Pitfalls of Investing In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Érudit Article "“eyes wide open”: E. W. Backus and The Pitfalls of Investing in Ontario’s Pulp and Paper Industry, 1902-1932" Mark Kuhlberg Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 16, n° 1, 2005, p. 201-233. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/015732ar DOI: 10.7202/015732ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 9 février 2017 07:32 chajournal2005.qxd 12/29/06 8:13 AM Page 201 “eyes wide open”: E. W. Backus and The Pitfalls of Investing in Ontario’s Pulp and Paper Industry, 1902-19321 Mark Kuhlberg Abstract It has long been argued that pulp and paper industrialists – especially Americans – could count on the cooperation of the provincial state as they established and expanded their enterprises in Canada in the first half of the twentieth century. -

OHS Bulletin May 2013 Executive Director’S Report

OHS B ULLETIN THE NEWSLETTER OF THE ONTARIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY I ss UE 187 M AY 2013 Peterborough’s Hutchinson House Celebrates 175 Years Saturday, June 22, 2013 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation R.R. 6, Hagersville, Ontario The 125th Annual General Meeting and Honours and Awards Ceremony of The Ontario Historical Society in partnership with and hosted by Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation (MNCFN) Highlights also include… • Traditional ceremony to celebrate the grand opening of Photo PHS the MNCFN’s new community centre utchison House Museum, garden. • Keynote address and First Nations book launch of Don Hwhich is owned and operated To mark this important anniver- Smith’s Mississauga Portraits: Ojibwe Voices from by the Peterborough Historical sary, the PHS held a celebration Nineteenth-Century Canada, including Allan Sherwin, Society (PHS), recently celebrat- with special guests that included author of Bridging Two Peoples: Chief Peter E. Jones ed its 175th anniversary. Built Ken Armstrong, the President of • Unveiling of Battle of York display by the citizens of Peterborough the PHS at the time the museum • Marketplace and exhibits in 1837 to convince Dr. John was developed, restoration ar- Hutchison not to move his chitect Peter John Stokes, OHS Registration and Lunch: $15 • Register by June 14 medical practice to Toronto, the Past President Jean Murray Cole 1.866.955.2755 or [email protected] residence was acquired by the PHS and PHS Honorary President and www.ontariohistoricalsociety.ca/agm in 1969. current chair of the Ontario Heri- The building was restored to tage Trust, Dr. -

OAC Review Volume 43 Issue 9, April 1931

April, 1931 Vol. XLNI No. 9 A De Laval Cream Separator saves and makes money twice a day, 365 days a year. It is the best paying machine any farmer can own, and the new De Laval is the world’s best cream sepa¬ rator. It is a pleasure and source of satisfaction to own, and will soon pay for itself. e Laval 3,000, ooo A.SERIES .A —Combines the easiest running with cleanest skimming. —Equipped with ball bearings throughout, protected against rust and corrosion. —Has the famous De Laval “floating” bowl with trailing discharge. —Improved oiling system with sight oil window. —Two-length crank, on larger siz¬ es, makes for easier operation. —Beautiful and durable gold and black finish. Sold on easy payments or monthly installments. Trade-in allowance See your De Laval dealer about made on old separator. Also three trying a new De Laval, or write other series of De Laval Separators nearest office below. for every need and purse. The cream separator has been the greatest factor in developing the dairy industry to the largest and most profitable branch of agriculture, and throughout the world wherever cows are milked the De Laval is the standard by which all other separators are judged. The De Laval Company, Ltd. Peterborough Montreal Winnipeg Vancouver THE O. A. C. REVIEW 413 ; ': a ; HOUSE:; INSULATION A NEW 8DEA A house lined with Cork is warmer in winter and cooler in summer. Fuel bills are reduced fully 30 per cent. Armstrong's Corkboard has kept the heat out of cold storage rooms for the past thirty years. -

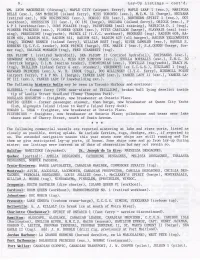

9. Lay-Up Listings - Cont'd

9. Lay-Up Listings - cont'd. WM. LYON MACKENZIE (firetug), MAPLE CITY (airport ferry), MAPLE LEAF 1 (exc. ), MARIPOSA BELLE (exc. ), SAM McBRIDE (island ferry), MISS TORONTO (exc. ), M. T. M. 11 (barge), NELVANA (retired exc. ), NEW BEGINNINGS (exc. ), NORDIC H20 (exc. ), NORTHERN SPIRIT 1 (exc. ), 007 (workboat), OBSESSION III (exc. ), OC 181 (barge), ONGIARA (island ferry), ORIOLE (exc. ), P & P 1 (workboat/exc. ), OURS POLAIRE (tug), PATHFINDER (sail training), PATRICIA D. 1 (tug), PIONEER PRINCESS (exc. ), PIONEER QUEEN (exc. ), PITTS CARILLON (barge), PLAYFAIR (sail trai ning), PRESCOTONT (tug/yacht), PRINCE II (I. Y. C. workboat), PROGRESS (tug), RADIUM 603, RA DIUM 604, RADIUM 610, RADIUM 611, RADIUM 623, RADIUM 625 (all barges), RADIUM YELLOWKNIFE (tug), THOMAS RENNIE (island ferry), WILLIAM REST (tug), RIVER GAMBLER (exc. ), HAROLD S. ROBBINS (Q.C. Y. C. tender), ROCK PRINCE (barge), STE. MARIE I (exc. ), S.A. QUEEN (barge, for mer tug), SALVAGE MONARCH (tug), FRED SCANDRETT (tug). SEA FLIGHT I (retired hydrofoil), SEA FLIGHT II (retired hydrofoil), SHIPSANDS (exc. ), SHOWBOAT ROYAL GRACE (exc. ), MISS KIM SIMPSON (exc. ), STELLA BOREALIS (exc. ), T. H. C. 50 (derrick barge), T. I. M. (marina tender), TORONTONIAN (exc. ), TORVILLE (tug/yacht), TRACY M. (tug), TRILLIUM (island ferry & exc. steamer), VERENDRYE (ex C. C. G. S. ), VIGILANT 1 (tug), WAYWARD PRINCESS (exc. ), W. B. INDOK (tug), DOC WILLINSKY (I. Y. C. ferry), WINDMILL POINT (airport ferry), Y & F NO. 1 (barge), YANKEE LADY (exc. ), YANKEE LADY II (exc. ), YANKEE LA DY III (exc. ), YANKEE LADY IV (newbuilding exc. ). The following historic hulls may be seen in Toronto Harbour and environs: BLUEBELL - former ferry (1906 near-sister of TRILLIUM), broken hull lying derelict inside tip of Leslie Street Headland (Tommy Thompson Park). -

THE 1866 FENIAN RAID on CANADA WEST: a Study Of

` THE 1866 FENIAN RAID ON CANADA WEST: A Study of Colonial Perceptions and Reactions Towards the Fenians in the Confederation Era by Anthony Tyler D’Angelo A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2009 Copyright © Anthony Tyler D’Angelo, 2009 Abstract This thesis examines Canada West’s colonial perceptions and reactions towards the Fenian Brotherhood in the Confederation era. Its focus is on the impact of the Fenians on the contemporary public mind, beginning in the fall of 1864 and culminating with the Fenian Raid on the Niagara frontier in June 1866. Newspapers, sermons, first-hand accounts, and popular poems and books from the time suggest the Fenians had a significant impact on the public mind by nurturing and reflecting the province’s social and defensive concerns, and the Raid on Canada West was used by contemporaries after the fact to promote Confederation and support a young Canadian identity. ii Writing a thesis is sometimes fun, often frustrating and always exacting, but its completion brings a satisfaction like no other. I am grateful to Queen’s University and the Department of History for giving me the opportunity to pursue this study; its completion took far longer than I thought, but the lessons learned were invaluable. I am forever indebted to Dr. Jane Errington, whose patience, knowledge, guidance and critiques were as integral to this thesis as the words on the pages and the sources in the bibliography. I cannot imagine steering the murky waters of historiography and historical interpretation without her help. -

Letters from the Depression

Letters from the Depression Grade 10: Canadian History Since World War I Letter to the Premier, January 13, 1933 Premier George S. Henry correspondence Reference Code: RG 3-9-0-391 Overview All of the Archives of Ontario lesson plans have two components: The first component introduces students to the concept of an archive and why the Archives of Ontario is an important resource for learning history The second component is content-based and focuses on the critical exploration of a historical topic that fits with the Ontario History and Social Studies Curriculum for grades 3 to 12. This plan is specifically designed to align with the Grade 10: Canadian History Since World War I curricula. We have provided archival material and an activity for you to do in your classroom. You can do these lessons as outlined or modify them to suit your needs. In this plan, students will read original letters written to Ontario Premier George S. Henry during the Depression to understand the hardships faced by families. Following comprehensive and analytical questioning and discussion, students will write a newspaper article using the letters as evidence. This lesson is designed to assist students in developing a sense of historical perspective for people who lived through the Great Depression. Page │1 Curriculum Connections Overall Expectations – Academic (CHC2D) Communities: Local, National, and Global - analyse the impact of external forces and events on Canada and its policies since 1914; Social, Economic, and Political Structures - analyse how changing economic and social conditions have affected Canadians since 1914; - analyse the changing responses of the federal and provincial governments to social and economic pressures since 1914. -

EW Backus and the Pitfalls of Investing in Ontario's Pulp And

Document generated on 09/26/2021 5:08 a.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada “eyes wide open”: E. W. Backus and The Pitfalls of Investing in Ontario’s Pulp and Paper Industry, 1902-1932 Mark Kuhlberg Volume 16, Number 1, 2005 Article abstract It has long been argued that pulp and paper industrialists – especially URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/015732ar Americans – could count on the cooperation of the provincial state as they DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/015732ar established and expanded their enterprises in Canada in the first half of the twentieth century. The case of Edward Wellington Backus, an American See table of contents industrialist, demonstrates that this paradigm does not explain the birth and dynamic growth of the newsprint industry in Ontario during this period. Backus rarely received the provincial government’s cooperation as he built Publisher(s) paper plants in Fort Frances and Kenora. On the rare occasions when the politicians assisted him, they only did so within carefully prescribed limits. The Canadian Historical Association/La Société historique du Canada Backus’s story is significant because it indicates that it is time to reconsider the history of the political economy of Canada’s resource industries, at least as far ISSN as turning trees into paper is concerned. 0847-4478 (print) 1712-6274 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Kuhlberg, M. (2005). “eyes wide open”: E. W. Backus and The Pitfalls of Investing in Ontario’s Pulp and Paper Industry, 1902-1932. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 16(1), 201–233. -

The Day of Sir John Macdonald – a Chronicle of the First Prime Minister

.. CHRONICLES OF CANADA Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton In thirty-two volumes 29 THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD BY SIR JOSEPH POPE Part VIII The Growth of Nationality SIR JOHX LIACDONALD CROSSING L LALROLAILJ 3VER TIIE XEWLY COSSTRUC CANADI-IN P-ICIFIC RAILWAY, 1886 From a colour drawinrr bv C. \TT. Tefferv! THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD A Chronicle of the First Prime Minister of the Dominion BY SIR JOSEPH POPE K. C. M. G. TORONTO GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY 1915 PREFATORY NOTE WITHINa short time will be celebrated the centenary of the birth of the great statesman who, half a century ago, laid the foundations and, for almost twenty years, guided the destinies of the Dominion of Canada. Nearly a like period has elapsed since the author's Memoirs of Sir John Macdonald was published. That work, appearing as it did little more than three years after his death, was necessarily subject to many limitations and restrictions. As a connected story it did not profess to come down later than the year 1873, nor has the time yet arrived for its continuation and completion on the same lines. That task is probably reserved for other and freer hands than mine. At the same time, it seems desirable that, as Sir John Macdonald's centenary approaches, there should be available, in convenient form, a short r6sum6 of the salient features of his vii viii SIR JOHN MACDONALD career, which, without going deeply and at length into all the public questions of his time, should present a familiar account of the man and his work as a whole, as well as, in a lesser degree, of those with whom he was intimately associated. -

The Formation of the Canadian Industrial

THE FORMATION OF THE CANADIAN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SYSTEM DURING WORLD WAR TWO Laurel Sefton MacDowell University of Toronto I The war years were a period of antagonistic labour-government rela tions and serious industrial unrest, which labour attributed to wage con trols, the failure of the government to consult on policies which directly affected employees, and the inadequacy of the existing collective bargain ing legislation. As a result, trade unions organized aggressively in the new war industries, struck with increasing frequency, and eventually became involved in direct political activity. At the centre of this conflict was the demand for collective bargaining. Collective bargaining was not just a means of raising wages and improving working conditions. It was a de mand by organized workers for a new status, and the right to participate in decision making both in industry and government. Thus, it became an issue not only on the shop floor where employers and unions met directly, but also in the political arena.1 Eventually this demand for a new status in society, was met by the introduction of a new legislative framework for collective bargaining which has been modified only slightly since that time. Yet in order to appreciate the evolution of this policy it is insuffi cient to consider simply the political debate or the crises which precipi tated the change. Even the important strikes which crystallized labour's discontent and prompted specific concessions, took place within the spe cial context of the war economy and a general realignment of industrial and political forces. Over a period of years, the economic tensions as sociated with the war generated pressures for reform which could not be contained. -

The Toronto Islands Customizing Menus

WELCOME TO THE TORONTO ISLANDS WELCOME TO THE TORONTO ISLANDS Whether you’re planning a corporate cocktail reception or a large-scale party, our multi faceted event company willWhether help t oy ou’markee planning your event a corpo a success.rate cocktail From weddings reception to or corpo a larrge-scaleate picnics, par team-buildingty, our multi-faceted events, e priventvate company parties, will help to make yfouresti evvalsent and a success. more, we F rpomrovide corpo a uniquerate picnics, oppo rteam-buildingtunity and a prime events, location. private parties, festivals, weddings and more, we provide a unique opportunity and a prime location. The Toronto Islands are made up of picturesque sites nestled in over 600 acres of parkland. Choose from a Thevariety Toron oft ounfo Islandsrgettable are made settings, up of including more than count 40 lpicnicess picnic, sites thenestled Toron int oo vIslander 600 BBQ acres and of beerparkland. co.’s upperChoose patio, from a variety of unforgettable settings, includingand countless the beach picnic house areas, ba rthe. Toronto Island BBQ and Beer Co. and the Beach Bar. CUSTOMIZING MENUS ChooseChoose ffrromom one a variety of the of variety menus of wemenus have we designed, have created, or use or our use cr oureati expeve expertisertise to helpto help you c createreate a a personali personalizzeded menu for your event. Please do not hesitate to contact our event coordinator if you have any questions. Centre Island Catering offers a variety of pre-set menu options that will delight your taste buds and help make your event-planning process a breeze. -

Kelakos, Finally Gets Their Due with 'Uncorked' Cd

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: OBSCURE SEVENTIES BAND WITH TIES TO EIGHTIES ROCK, KELAKOS, FINALLY GETS THEIR DUE WITH 'UNCORKED' CD The early 21st century has seen the rediscovery of several rock acts from yesterday that failed to get their due back when they were recording and playing gigs (artists such as Pentagram and Rodriguez immediately come to mind). And there is another overlooked '70s act that should finally get the attention they deserved the first time around - Kelakos. Recording and working out of Ithaca, NY, Kelakos was composed of singer/guitarist George Michael Kelakos Haberstroh, guitarist Mark Sisson, bassist Lincoln Bloomfield, and drummer Carl Canedy. Kelakos issued its first single in 1976 and an 11-song album in September 1978, 'Gone Are the Days,' which sounds impressively on par with favorite cuts that classic rock radio stations have been playing for the past few decades. And now, record collectors and musicologists will be able to hear the music of Kelakos, with the fully-remixed release of the 15-track disc, 'Uncorked: Rare Tracks From A Vintage '70s Band,' which contains such standouts as “Gone Are the Days” and “How Did You Get So Crazy” (which were also released as a single way back when), and the memorable “Frostbite Fantasy” as well as a never before released track, "In the Sun." And if one of the band members' names sounds familiar, it should: Canedy is the long- time drummer for heavy metal vets the Rods, in addition to producing classic releases in the '80s by such bands as Anthrax, Overkill, TT Quick, Exciter, and Possessed, among others, and a solo release “Headbanger” in 2014.