Mapping Ancient Production and Trade of Copper in Oman and Obsidian in Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Akkadian Empire

RESTRICTED https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/the-akkadian-empire/ The Akkadian Empire LEARNING OBJECTIVE • Describe the key political characteristics of the Akkadian Empire KEY POINTS • The Akkadian Empire was an ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia, which united all the indigenous Akkadian speaking Semites and the Sumerian speakers under one rule within a multilingual empire. • King Sargon, the founder of the empire, conquered several regions in Mesopotamia and consolidated his power by instating Akaddian officials in new territories. He extended trade across Mesopotamia and strengthened the economy through rain-fed agriculture in northern Mesopotamia. • The Akkadian Empire experienced a period of successful conquest under Naram-Sin due to benign climatic conditions, huge agricultural surpluses, and the confiscation of wealth. • The empire collapsed after the invasion of the Gutians. Changing climatic conditions also contributed to internal rivalries and fragmentation, and the empire eventually split into the Assyrian Empire in the north and the Babylonian empire in the south. TERMS Gutians A group of barbarians from the Zagros Mountains who invaded the Akkadian Empire and contributed to its collapse. Sargon The first king of the Akkadians. He conquered many of the surrounding regions to establish the massive multilingual empire. Akkadian Empire An ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia. Cuneiform One of the earliest known systems of writing, distinguished by its wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets, and made by means of a blunt reed for a stylus. Semites RESTRICTED Today, the word “Semite” may be used to refer to any member of any of a number of peoples of ancient Southwest Asian descent, including the Akkadians, Phoenicians, Hebrews (Jews), Arabs, and their descendants. -

The Ancient Mesopotamian Place Name “Meluḫḫa”

THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN PLACE NAME “meluḫḫa” Stephan Hillyer Levitt INTRODUCTION The location of the Ancient Mesopotamian place name “Meluḫḫa” has proved to be difficult to determine. Most modern scholars assume it to be the area we associate with Indus Valley Civilization, now including the so-called Kulli culture of mountainous southern Baluchistan. As far as a possible place at which Meluḫḫa might have begun with an approach from the west, Sutkagen-dor in the Dasht valley is probably as good a place as any to suggest (Possehl 1996: 136–138; for map see 134, fig. 1). Leemans argued that Meluḫḫa was an area beyond Magan, and was to be identified with the Sind and coastal regions of Western India, including probably Gujarat. Magan he identified first with southeast Arabia (Oman), but later with both the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf of Oman, thus including the southeast coast of Iran, the area now known as Makran (1960a: 9, 162, 164; 1960b: 29; 1968: 219, 224, 226). Hansman identifies Meluḫḫa, on the basis of references to products of Meluḫḫa being brought down from the mountains, as eastern Baluchistan in what is today Pakistan. There are no mountains in the Indus plain that in its southern extent is Sind. Eastern Baluchistan, on the other hand, is marked throughout its southern and central parts by trellised ridges that run parallel to the western edge of the Indus plain (1973: 559–560; see map [=fig. 1] facing 554). Thapar argues that it is unlikely that a single name would refer to the entire area of a civilization as varied and widespread as Indus Valley Civilization. -

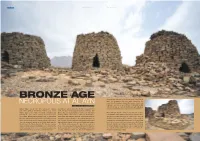

BRONZE AGE the Next Few Centuries in the Biggest Part of the Middle East

June 26, 2012 Issue 226 June 26, 2012 Issue 226 BRONZE AGE the next few centuries in the biggest part of the Middle East. The language of the new empire came from the NECROPOLIS AT AL AYN same Semitic language groups like modern Arabic and Thoughts & Photography | Jerzy Wierzbicki Hebrew. Even now, a few numbers of Akkadian words still exist in Iraq; we can still find people with Akkadian Middle East raised the first advanced cultures According to authors Marc Van De Mieroop and Daniel personal and tribal names, especially local Christians. and other political formations; without any doubt, Potts, the last archaeological research confirmed that Middle East is the cradle of human civilisation and Bronze Age city-states had been connected with many Even during the war, the cultural contacts between cities probably the place where history of humans began. faraway cultural centres in the central Asia, North Africa, in the Middle East and Africa were very strong. Two cities, In southern Mesopotamia (present Iraq), in the Middle Indus valley and Arabian Peninsula. These trade activities specialised in trade with ancient cultures were living at East, the Sumerians had invented the first writing system, spread not only merchandises, but cultural inventions as that time in the modern GCC countries. Archaeological which quickly developed the human culture in this region. well. The end of the third millennium brought about the next excavations confirmed that the ancient city Ur and Suza The real prosperity period in the Middle East was the big civilisation change in the ancient Middle East culture had a lot of contact with two ancient states like Dilmun Bronze Age in the third millennium BC; this was a golden - the Akkadian King Sargon the Great had conquered (modern Bahrain) and Magan (currently the Sultanate time for human culture in the Middle East. -

Before the Emirates: an Archaeological and Historical Account of Developments in the Region C

Before the Emirates: an Archaeological and Historical Account of Developments in the Region c. 5000 BC to 676 AD D.T. Potts Introduction In a little more than 40 years the territory of the former Trucial States and modern United Arab Emirates (UAE) has gone from being a blank on the archaeological map of Western Asia to being one of the most intensively studied regions in the entire area. The present chapter seeks to synthesize the data currently available which shed light on the lifestyles, industries and foreign relations of the earliest inhabitants of the UAE. Climate and Environment Within the confines of a relatively narrow area, the UAE straddles five different topographic zones. Moving from west to east, these are (1) the sandy Gulf coast and its intermittent sabkha; (2) the desert foreland; (3) the gravel plains of the interior; (4) the Hajar mountain range; and (5) the eastern mountain piedmont and coastal plain which represents the northern extension of the Batinah of Oman. Each of these zones is characterized by a wide range of exploitable natural resources (Table 1) capable of sustaining human groups practising a variety of different subsistence strategies, such as hunting, horticulture, agriculture and pastoralism. Tables 2–6 summarize the chronological distribution of those terrestrial faunal, avifaunal, floral, marine, and molluscan species which we know to have been exploited in antiquity, based on the study of faunal and botanical remains from excavated archaeological sites in the UAE. Unfortunately, at the time of writing the number of sites from which the inventories of faunal and botanical remains have been published remains minimal. -

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigation Jump to search "UAE" redirects here. For other uses, see UAE (disambiguation). Coordinates: 24°N 54°E / 24°N 54°E United Arab Emirates (Arabic) اﻹﻣﺎرات اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة al-ʾImārāt al-ʿArabīyyah al-Muttaḥidah Flag Emblem ﻋﻴﺸﻲ ﺑﻼدي :Anthem "Īšiy Bilādī" "Long Live My Nation" Location of United Arab Emirates (green) in the Arabian Peninsula (white) Abu Dhabi Capital 24°28′N 54°22′E / 2 4.467°N 54.367°E Dubai Largest city 25°15′N 55°18′E / 25.250°N 55.300°E Official languages Arabic 11.6% Emirati 59.4% South Asian Ethnic groups (38.2% Indian, 9.4% Pakistani, 9.5% Bangladeshi) (2015)[1] 10.2% Egyptian 6.1% Filipino 12.8% Others Religion Islam Demonym(s) Emirati[1] Federal elective constitutional Government monarchy[2] • President Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan Mohammed bin Rashid Al • Prime Minister Maktoum • Speaker Amal Al Qubaisi Legislature Federal National Council Establishment from the United Kingdom and the Trucial States • Ras al-Khaimah 1708 • Sharjah 1727 • Abu Dhabi 1761 • Ajman 1816 • Dubai 1833 • Fujairah 1952 • Independence 2 December 1971 • Admitted to the 9 December 1971 United Nations • Admission of Ras 10 February 1972 al-Khaimah to the UAE Area 2 • Total 83,600 km (32,300 sq mi) (114th) • Water (%) negligible Population • 2018 estimate 9,599,353[3] (92nd) • 2005 census 4,106,427 • Density 99/km2 (256.4/sq mi) (110th) GDP (PPP) 2018 estimate • Total $732.861 billion[4] (32nd) • Per capita $70,262[4] (7th) GDP (nominal) 2018 estimate • Total $432.612 -

The Iasa Bulletin

Number 24, 2019 Price: £5.00 THE IASA BULLETIN The Latest News and Research in the Arabian Peninsula International Association for the Study of Arabia (IASA) International Association for the Study of Arabia (IASA) formerly the British Foundation for the Study of Arabia Publications IASA Trustees Bulletin Mr Daniel Eddisford (Editor), Ms Carolyn Perry Mr William Facey (Book Reviews), Chair Ms Carolyn Perry Dr Tim Power (Research), Mr Daniele Martiri Treasurer Mr Simon Alderson Dr Derek Kennet, Dr St John Simpson Hon. Secretary Mr Daniel Eddisford Monographs (Editors) Website Co-ordinator Dr Robert Wilson PSAS Mr Daniel Eddisford (Editor) Prof Dionisius Agius FBA, Ms Ella Al-Shamahi Dr Robert Bewley, Dr Noel Brehony CMG, Seminar for Arabian Studies Dr Robert Carter, Prof Clive Holes FBA Dr Julian Jansen van Rensburg (Chair, Assistant Editor), Dr Dr Derek Kennet, Mr Michael Macdonald FBA Robert Wilson (Treasurer), Mr Daniel Eddisford (Secretary), Orhan Elmaz (Assistant Editor), Dr Harry Munt (Assistant Grants Editor), Dr Tim Power (Assistant Editor), Prof Robert Carter, Dr Bleda Düring, Dr Nadia Durrani, Dr Derek Kennet, Dr Chair Dr Derek Kennet Dr Clive Holes, Dr Nadia Durrani Jose Carvajal Lopez, Mr Michael C.A. Macdonald FBA, Dr Janet Watson Events Additional Members of PSAS Committee Prof Alessandra Avanzini, Prof Soumyen Bandyopadhyay, Lectures Ms Carolyn Perry, Mr Alan Hall, Dr Ricardo Eichmann, Prof Clive Holes, Prof Khalil Al- Ms Marylyn Whaymand Muaikel, Prof Daniel T. Potts, Prof Christian J. Robin, Prof Lloyd Weeks Notes for contributors to the Bulletin The Bulletin depends on the good will of IASA members and correspondents to provide contributions. -

Hafit Tombs in the Wadi Al-Jizzi and Wadi Suq Corridors

Hafit tombs in the Wadi al-Jizzi and Wadi Suq corridors Samatar Ahmed Botan Photo on the cover: A cluster of Hafit tombs in the Wadi al Jizzi. Picture taken by the WAJAP team. Hafit tombs in the Wadi al-Jizzi and Wadi Suq corridors. A spatial analysis of Early Bronze Age (3200-2500 BC) funerary structures in the Sultanate of Oman. Sam Botan S0701084 Course: MA Thesis Course code: ARCH 1044WY Supervisor : Dr. B.S. Düring. Specialization: Archaeology of the Near East University of Leiden, Faculty of Archaeology Leiden, final version Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 Research questions and thesis outline ............................................................................. 9 Chapter 1: The Hafit period on the Oman peninsula .................................................. 11 1.1 The Neolithic and Bronze Age climate .................................................................. 11 1.2 The Hafit period (3200-2500 BC) .......................................................................... 13 1.3 Hafit tombs ............................................................................................................. 21 1.4 Other types of tombs in the study area ................................................................... 25 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 31 Chapter 2: Theoretical framework ............................................................................... -

MOBILITY, EXCHANGE, and TOMB MEMBERSHIP in BRONZE AGE ARABIA: a BIOGEOCHEMICAL INVESTIGATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial F

MOBILITY, EXCHANGE, AND TOMB MEMBERSHIP IN BRONZE AGE ARABIA: A BIOGEOCHEMICAL INVESTIGATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lesley Ann Gregoricka, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Anthropology The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Clark Spencer Larsen, Advisor Joy McCorriston Samuel D. Stout Paul W. Sciulli Copyright by Lesley Ann Gregoricka 2011 ABSTRACT Major transitions in subsistence, settlement organization, and funerary architecture accompanied the rise and fall of extensive trade complexes between southeastern Arabia and major centers in Mesopotamia, Dilmun, Elam, Central Asia, and the Indus Valley throughout the third and second millennia BC. I address the nature of these transformations, particularly the movements of people accompanying traded goods across this landscape, by analyzing human and faunal skeletal material using stable strontium, oxygen, and carbon isotopes. Stable isotope analysis is a biogeochemical technique utilized to assess patterns of residential mobility and paleodiet in archaeological populations. Individuals interred in monumental communal tombs from the Umm an-Nar (2500-2000 BC) and subsequent Wadi Suq (2000-1300 BC) periods from across the Oman Peninsula were selected, and the enamel of their respective tomb members analyzed to detect (a) how the involvement of this region in burgeoning pan- Gulf exchange networks may have influenced mobility, and (b) how its inhabitants reacted during the succeeding economic collapse of the early second millennium BC. Due to the commingled and fragmentary nature of these remains, the majority of enamel samples came from a single tooth type for each tomb (e.g., LM1) to prevent ii repetitive analysis of the same individual. -

Rethinking Some Aspects of Trade in the Arabian Gulf Author(S): D

Rethinking Some Aspects of Trade in the Arabian Gulf Author(s): D. T. Potts Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 24, No. 3, Ancient Trade: New Perspectives (Feb., 1993), pp. 423-440 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/124717 Accessed: 30-10-2018 13:58 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Archaeology This content downloaded from 128.148.231.34 on Tue, 30 Oct 2018 13:58:48 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Rethinking some aspects of trade in the Arabian Gulf D. T. Potts Introduction Ever since the publication of A. L. Oppenheim's seminal review of UET V (Oppenheim 1954) the dynamics of Bronze Age trade in the Arabian Gulf have been a subject of endless fascination for both archaeologists and Assyriologists. The literature on this subject has become enormous, and I am only presuming to add yet another paper to an already swelling corpus because the ongoing excavations at Tell Abraq have brought to light what is in some cases unique material which, as my title suggests, calls for a reconsideration of certain ideas, both new and old, in this field. -

Human Anatomy and Physiology

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY FULLERTON OSHER LIFELONG LEARNING INSTITUTE “The World, its Resources, and the Humankind” Edgar M. Moran, M.D. Professor of Medicine, Emeritus University of California, Irvine 1 WHY THIS NEW COURSE? • A life-time preoccupation about world resources and their impact on human development • Human settlements and life depend on resources economy of life social life politics civilization culture • The world is a complex physical-chemical and biological phenomenon in continuous evolution E. MORAN - 2017 2 WHAT DO WE NEED FOR THIS COURSE? 1. Some knowledge of geography 2. Some knowledge of history 3. Some knowledge of how things work and human relationships 4. Abandon any bias. Keep an open mind 5. Willingness to acquire new knowledge Bibliography is provided E. MORAN - 2017 3 WHAT I WILL AND WHAT I WILL NOT DO I will answer questions I will avoid giving medical consultations I will regret absences I advice not to miss lectures because of their interconnection and Lecture topics may extend on more than one session I will avoid talking about religion I will avoid talking about politics My aim is to stimulate wonder, thought, and knowledge E. MORAN - 2017 4 “KNOWLEDGE IS POWER” SOCRATES (469–399 BCE) 5 DISCLAIMER Nothing to declare Source of data: • Personal files, notes, and photos • Textbooks, journals • Internet E. MORAN - 2017 6 The World, its Resources, and Humankind. Topics of Study The World Place, History, Economy, Politics Resources Humankind 7 PLAN OF STUDY Eight sessions Resources to be reviewed: • Air • Water • Food • Metals and Minerals • Construction materials • Energy: Renewable: Solar, water, wind, and nuclear • Energy: Coal, oil, and natural gas Comments on: • Geography • History • Economy • Politics E. -

United Arab Emirates Country Handbook This

United Arab Emirates Country Handbook This handbook provides basic reference information on the United Arab Emirates, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and transportation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military per sonnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to the United Arab Emirates. The Marine Corps Intel ligence Activity is the community coordinator for the Country Hand book Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on the United Arab Emirates. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for training. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this docu ment, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. CONTENTS KEY FACTS .................................................................... 1 U.S. MISSION ................................................................. 2 U.S. Embassy .............................................................. 2 U.S. Consulate ........................................................... -

The Most Ancient Trace on the Commercial and Civilizational Relations Between

The most ancient trace on the commercial and civilizational relations between Mesopotamia and China By Dr. Bahnam Abu Al-Souf: The ancient Iraqis needed about eight thousand years, a number of raw materials to make their tools and weapons and those materials were not available or they were rare in Mesopotamia. The children and women's needs for the make-up required bringing all kinds of valuable pearls and shells, most of which were not found in various Iraqi areas. With the progress growth of the first agricultural villages in Northern and central Iraq and with their increase in number during the 6th and 5th millennium B.C., and due to the development of the social life in those first villages and the spread of many beliefs and religious practices related to the fertility, land, birth and magic powers of certain symbols and things the Iraqis who inhabited those villages brought kinds of shells from the coast of the Mediterranean sea and the Persian gulf carnelian from the Southern parts of the Arabian peninsula and from the eastern parts of Iran. They also got lapis-lazuli from its mining areas in Badkashan in the Northern Afghanistan. They also brought copper from Oman in the Persian Gulf and gold, silver and copper from Anatolia (1) and cedar woods from the mounta1ns of Lebanon. (2) There were two main roads to bring the materials from Anatolia. The first one came from the center and Southern parts of Asia minor, passing through town in Northern Syria, where it divided into two branches, one of them going southwards towards Palestine and then went westwards to Sinai and Egypt.