New Europe College GE-NEC Program 2004-2005 2005-2006 2006-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MA Thesis Ceremonials FINAL

ABSTRACT CEREMONIALS: A RECLAMATION OF THE WITCH THROUGH DEVISED RITUAL THEATRE by Rachel Lynn Brandenburg Rituals have been used throughout history as a way to process change and emotion. In the modern day, people are beginning to turn away from organized religion and to take on more personalized rituals and spirituality. As such, identifying as a witch is a growing phenomenon that serves to empower many personally, politically, and spiritually. This creative thesis takes an autobiographical approach to explore how ritual and the identity of the witch can be used as tools of empowerment, tracing the artist’s own journey from Catholicism to a more fluid spiritual life. On February 22nd, 2019, Ceremonials: A Ritual Play opened as part of Miami University’s Independent Artist Series. The play was devised with a student ensemble over a period of five months and stands as the culmination of a series of performance projects that sought to combine ritual and theatre. This portfolio spans the breadth of that practice-based research and includes examples from performance experiments and the devising process, as well as reflections on how ritual and devised theatre can help to empower the individual and the artist. CEREMONIALS: A RECLAMATION OF THE WITCH THROUGH DEVISED RITUAL THEATRE A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Rachel Lynn Brandenburg Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2019 Advisor: Saffron Henke Reader: Julia Guichard Reader: Christiana Molldrem Harkulich ©2019 Rachel Lynn Brandenburg This Thesis titled CEREMONIALS: A RECLAMATION OF THE WITCH THROUGH DEVISED RITUAL THEATRE by Rachel Lynn Brandenburg has been approved for publication by The College of Creative Arts and Department of Theatre ____________________________________________________ Saffron Henke, MFA ______________________________________________________ Julia Guichard, MFA _______________________________________________________ Christiana Molldrem Harkulich, PhD Table of Contents 1. -

Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’S Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota

Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota One of the most striking qualities in Florence + the Machine’s music is the sonic soundscape and vocal timbre. This paper provides a close reading of a cross-section of three songs from the album Ceremonials while considering the timbres employed and connecting those timbres to narrative implications. This presentation will begin with a brief overview of Florence + the Machine, followed by an explanation of the methodology employed. After identifying and classifying timbre types present in the selected songs, I will address how Kate Heidemann’s 2016 system can be used “to conceptualiz[e] the meaning of timbre,” (2016). I posit that Florence Welch employs specific timbre types to represent Renaissance ideas and to offer deeper insight to the narratives unfolding. Finally, I will conclude with remarks on possible future scholarship. Florence + the Machine is a British indie-pop-rock band that consists of lead singer Florence Welch, back-up singers, and supporting instrumentalists, including a harpist, guitarist, and keyboardist. Since their formation in 2007, Florence + the Machine has released four studio albums, and Florence Welch has collaborated with many well-known contemporary pop artists, as well as produced music for films and video games. Ceremonials (2011) has been described as a more cohesive and representative album of the sonic soundscape than the group’s first album Lungs (2009), and as such offers an opportunity to begin to examine Florence + the Machine’s compositional techniques and intricacies, specifically regarding one of the most distinctive features of the group – that of the voice and vocal timbre. -

AUSTIN CITY LIMITS DOUBLE-BILL: FLORENCE + the MACHINE & ANDRA DAY New Episode Premieres October 22 On

AUSTIN CITY LIMITS DOUBLE-BILL: FLORENCE + THE MACHINE & ANDRA DAY New Episode Premieres October 22 on PBS Austin, TX—October 20, 2016—Austin City Limits (ACL) presents a breathtaking hour with two of today’s most inspirational acts: Florence + the Machine in their return appearance and Andra Day in a standout ACL debut. The new installment airs October 22nd at 8pm CT/9pm ET as part of ACL’s new Season 42. The program airs weekly on PBS stations nationwide (check local listings for times) and full episodes are made available online for a limited time at pbs.org/austincitylimits immediately following the initial broadcast. Viewers can visit acltv.com for news regarding future tapings, episode schedules and select live stream updates. The show's official hashtag is #acltv. It’s been over five years since UK hitmakers Florence + the Machine first-appeared on the ACL stage. Now international superstars and one of rock’s biggest live acts, the unstoppable band make a triumphant return with a high-energy, buoyant five-song set. Dynamic leader Florence Welch dances barefoot across the stage performing songs from their recent, chart-topping LP How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful. Her knockout vocals and remarkable rapport with fans captivate throughout as she enlists the crowd as a “hungover choir of angels” for the Grammy- nominated “Shake It Out” from 2011’s Ceremonials, closing with a rapturous performance of the band’s 2009 breakthrough smash, the anthemic “Dog Days Are Over.” "Florence brings a unique performance art to all of her shows, and she took it to a new level this night,” says ACL executive producer Terry Lickona. -

View Booklet

Florence + the Machine CEREMONIALS 2 “Only If For A Night” And I had a dream And I heard your voice About my old school As clear as day And she was there all pink and gold and And you told me I should concentrate glittering It was all so strange I threw my arms around her legs And so surreal Came to weeping (came to weeping) That a ghost should be so practical Only if for a night And I heard your voice As clear as day And the only solution was to stand and fight And you told me I should concentrate And my body was bruised and I was set It was all so strange alight And so surreal But you came over me like some holy rite That a ghost should be so practical And although I was burning, you’re the only Only if for a night light Only if for a night And the only solution was to stand and fight And my body was bruised and I was set alight Madam, my dear, my darling But you came over me like some holy rite Tell me what all the sighing’s about And although I was burning, you’re the only light Tell me what all the sighing’s about Only if for a night And I heard your voice And the grass was so green against my new As clear as day clothes And you told me I should concentrate And I did cartwheels in your honour It was all so strange Dancing on tiptoes And so surreal My own secret ceremonials That a ghost should be so practical Before the service began Only if for a night In the graveyard doing handstands Only if for a night 3 “Shake It Out” Regrets collect like old friends Shake it out, shake it out, shake it out, Here to relive your darkest moments -

How Big How Blue How Beautiful Album Download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download

how big how blue how beautiful album download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download. 1. Ship to Wreck 2. What Kind of Man 3. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful 4. Queen Of Peace 5. Various Storms & Saints 6. Delilah 7. Long & Lost 8. Caught 9. Third Eye 10. St Jude’ 11. Mother 12. Hiding 13. Make Up Your Mind 14. Which Witch 15. Third Eye (Demo) 16. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful (Demo) 17. As Far As I Could Get. Tags: Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Leak Download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Leak Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful zip download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful album mp3 download Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album 320 kbps Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Leaked Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful has it leaked Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful (2015) Album Leak Download. Florence + the Machine – How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful Album Download. 1. Ship to Wreck 2. What Kind of Man 3. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful 4. Queen Of Peace 5. Various Storms & Saints 6. Delilah 7. Long & Lost 8. Caught 9. Third Eye 10. St Jude’ 11. Mother 12. Hiding 13. Make Up Your Mind 14. Which Witch 15. Third Eye (Demo) 16. How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful (Demo) 17. -

Isabella Summers (Isa Machine)

ISABELLA SUMMERS (ISA MACHINE) BIO “I always wanted to be the little girl that made rap records,” announces Isabella Summers –and yet elfin-like, Isa doesn’t look like your average hip-hop producer. Nor does she look like the kind of girl who directed horror films, bought her first MPC off the back of a lorry or co-wrote some of the biggest tracks of the last three years. But she’s done all of those things and this is just the beginning... In 2006, she worked on remixes for some of the indie bands that were hanging around her studios in Crystal Palace, London. Hanging around was amongst others, a girl called Florence. Fast-forward a few years, and Isabella has six co-writes on the critically acclaimed Florence + the Machine album ‘Lungs’ and three co-writes on the album ‘Ceremonials’. When she’s not on tour playing keys with FATM, Isabella is in the studio writing, producing and remixing tracks for an array of talented artists Isabella has recently added film and television scoring to her resume and is currently co-scoring Hulu’s ‘Little Fires Everywhere’ with Mark Isham. She also created the title theme for Sky Atlantic’s ‘Riviera’ and is co-scoring Amazon’s upcoming series ‘Panic.’ AWARDS & NOMINATIONS EMMY NOMINATION (2020) LITTLE FIRES EVERYWHERE Outstanding Music Composition for a "The Spider Web" Limited Series, Movie or Special (Original Dramatic Score) *Co-Composer with Mark Isham TELEVISION PANIC (Series) Adam Schroeder, Joe Roth, Jeff Amazon Prime Kirschenbaum, Leigh Janiak, Lauren *Co-Score with Brian Kim Oliver, Elle Triedman, exec prods. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums We Found Love a Thousand Years Talk That Talk Take Care 1 Rihanna Feat

28 November 2011 CHART #1801 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums We Found Love A Thousand Years Talk That Talk Take Care 1 Rihanna feat. Calvin Harris 21 Christina Perri 1 Rihanna 21 Drake Last week 1 / 10 weeks Platinum / Universal Last week 34 / 2 weeks WEA/Warner Last week - / 1 weeks Universal Last week 19 / 2 weeks Universal What Makes You Beautiful - The Sin... Don't Forget Your Roots Someone To Watch Over Me Concerto: One Night In Central Park 2 One Direction 22 Six60 2 Susan Boyle 22 Andrea Bocelli Last week 2 / 5 weeks Gold / SonyMusic Last week 15 / 19 weeks Platinum / Massive/Universal Last week 2 / 3 weeks Platinum / SonyMusic Last week 29 / 2 weeks Universal Sexy And I Know It Hangover Gravel And Wine Beyond The Sun 3 LMFAO 23 Taio Cruz feat. Flo Rida 3 Gin Wigmore 23 Chris Isaak Last week 3 / 10 weeks Platinum / Universal Last week 18 / 6 weeks Universal Last week 1 / 3 weeks Gold / Universal Last week - / 1 weeks Universal It Will Rain Black Sheep 21 Sorry For Party Rocking 4 Bruno Mars 24 Gin Wigmore 4 Adele 24 LMFAO Last week 4 / 9 weeks Gold / WEA/Warner Last week 20 / 9 weeks Universal Last week 6 / 44 weeks Platinum x7 / XL/Rhythm Last week 22 / 22 weeks Universal Only To Be Tonight Tonight Six60 - The Album Stronger 5 Six60 25 Hot Chelle Rae 5 Six60 25 Kelly Clarkson Last week 8 / 4 weeks Massive/Universal Last week 26 / 13 weeks Gold / SonyMusic Last week 4 / 7 weeks Platinum / Massive/Universal Last week 23 / 5 weeks SonyMusic Paradise The A Team Belle Love Changes Everything 6 Coldplay 26 Ed Sheeran 6 Bic Runga 26 Mz J Last week 9 / 8 weeks Gold / Parlophone/EMI Last week 38 / 2 weeks WEA/Warner Last week 5 / 2 weeks Gold / SonyMusic Last week 30 / 3 weeks MzJ/Isaac/Universal Good Feeling Dedication To My Ex (Miss That) Here And Now 19 7 Flo Rida 27 Lloyd feat. -

Wajdi Mouawad

programme eng 09 15/05/09 10:03 Page 1 63rd Festival d’Avignon 7-29 July 2009 Complement in English to the programme This document does not replace the full programme but complements it by offering an English translation of all the texts presenting the artists and shows of the festival. The page numbers refer to the programme in French where further details and full credits are also available. The Festival d’Avignon has long been an interna- Finally, a special programme has been prepared tional platform for the performing arts, gathering this summer: artists and audiences from all around the world. This year, the programme welcomes artists and • Some shows will benefit from English surtitles performances from many countries and many lan- or simultaneous translation into English. This guages will be heard on the festival stages: service will only be available for a limited number French from three different continents as well as of performances: English, Spanish, Italian, Arabic, Polish, German Le Livre d’or de Jan, Saturday 11th July at 10 p.m. and Hebrew. It is important to allow the artists to Les Inepties volantes, Friday 12 July at 10 p.m. express themselves in their own languages, but it Des témoins ordinaires,Wednesday 21 July at is also important tofacilitate access to their work 2.30 p.m. & Sunday 26 July at6p.m. for as wide an audience as possible. For many Les Cauchemars du gecko, Friday 24 July at 6 p.m. years we have provided French surtitles for the La Menzogna, Saturday 25 July at 10 p.m. -

Ritual and Ceremonials

Ritual and Ceremonials SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR 2019 Edition Ritual and Ceremonials of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War 2019 Edition Copyright 2019 Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, a Congressionally Chartered Corporation Updated and amended through the 137th National Encampment, August 2018, Framingham, Massachusetts Previous editions are obsolete. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part in any form without the written permission of the Commander-in-Chief of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. Summary of changes from the previous edition: 1. Addition of optional General Plan of the Meeting Room for Encampments 2. Addition of protocol section. 3. Addition of ceremony for receiving delegations from the Allied Orders. 4. Administrative changes have been made throughout the book, to include: typographical, grammatical and formatting corrections. TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL GUIDANCE Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 General Instructions .............................................................................................................. 2 CEREMONIES FOR CAMPS Opening ................................................................................................................................. 6 Order of Business .................................................................................................................. 8 Initiation (Short Form) ......................................................................................................... -

Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine's Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnes

Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 1. From Heidemann 2016 Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 2. From Lavengood 2017 (p. 76) Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 3. Florence Welch’s Timbre Types Example 4. Back-up Singer Timbre Types Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 5. “Seven Devils” Chorus Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 6. “Seven Devils” Final Chorus Example 7. “Seven Devils” Form Chart, Annotated with Timbre Types Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 8. “What the Water Gave Me” Post Chorus Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 9. “What the Water Gave Me” Penultimate Chorus Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota Example 10. “All This and Heaven, Too” Bridge Example 11. “All This and Heaven, Too” Form Chart Talking Timbre: Vocal Timbre and Narrative in Florence + the Machine’s Ceremonials Madison Stepherson University of Minnesota BIBLIOGRAPHY Timbre Blake, David K. 2012. “Timbre as Differentiation in Indie Music.” Music Theory Online 18 (2).i http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.2/mto.12.18.2.blake.php ––––––. -

Armanen Runes Rune Ceremonials

introduction Armanen Runes Rune Ceremonials Copyright© 1984 - 1998 by Karl Hans Welz All rights reserved. This course may not be reproduced as a whole or in part, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any means, electronic, photographic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing by the author. Published by Magitech Press P.O. Box 1298, Woodstock, GA 30188 Contents of the Book What this book will do for you What are the Basics? - Odin's Rune Song, the Magical Poem Access-Keywords, Meanings, and Corelations of Runes Body- and Hand Positions of Runes About Ceremonials, About Ceremonial Utensils, Preparations of the Utensils The Basic Ceremony Ceremonial for Success Ceremonial for Success, Simplified Version Chant for Success Ceremonial for Love Ceremonial for Love, Simplified Version Chant for Love Ritual to Change Bad Luck into Good Circumstances Chant for Change Calling of the Soulmate Ceremony of the Grostic Wedding Chant for Successful Creativity 1 introduction RUNE CEREMONIALS What these instructions will do for you Change! All life is continuous change! Some for the better, some for the worse. Every day we are confronted with new situations. Some pleasant, others less pleasant! We have to deal with them whether we want to do so or not. We can never be certain about the outcome, but we are working with all that we have available to get the best outcome possible that our imagination can create, and more, if we keep the desire open-ended. To influence the outcome of a specific situation we have many means available. -

Listener 100.Pdf

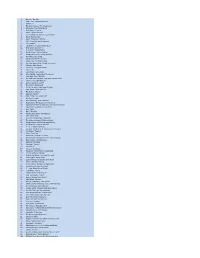

1 Bon Iver, 'Bon Iver' 2 Fleet Foxes, 'Helplessness Blues' 3 Adele, '21' 4 The Decemberists, 'The King Is Dead' 5 Radiohead, 'The King OF Limbs' 6 Black Keys, 'El Camino' 7 Wilco, 'The Whole Love' 8 Florence And The Machine, 'Ceremonials' 9 Beirut, 'The Rip Tide' 10 Foster The People, 'Torches' 11 M83, 'Hurry Up, We're Dreaming' 12 Feist, 'Metals' 13 Iron & Wine, 'Kiss Each Other Clean' 14 tUnE-yArDs, 'W h o k i l l' 15 St. Vincent, 'Strange Mercy' 16 The Civil Wars, 'Barton HolloW' 17 Death Cab For Cutie, 'Codes And Keys' 18 Tom Waits, 'Bad As Me' 19 My Morning Jacket, 'Circuital' 20 Bright Eyes, 'The People's Key' 21 Jay-Z And Kanye West, 'Watch The Throne' 22 Coldplay, 'Mylo Xyloto' 23 PJ Harvey, 'Let England Shake' 24 Cults, 'Cults' 25 James Blake, 'James Blake' 26 Gillian Welch, 'HarroW And The Harvest' 27 Lady Gaga, 'Born This Way' 28 The Head And The Heart, 'The Head And The Heart' 29 Lykke Li, 'Wounded Rhymes' 30 Childish Gambino, 'CAMP' 31 The Antlers, 'Burst Apart' 32 TV On The Radio, 'Nine Types OF Light' 33 Ryan Adams, 'Ashes And Fire' 34 The Strokes, 'Angles' 35 Wye Oak, 'Civilian' 36 Girls, 'Father, Son, Holy Ghost' 37 The Roots, 'undun' 38 Arctic Monkeys, 'Suck It And See' 39 Beastie Boys, 'Hot Sauce Committee Pt. 2' 40 Explosions In The Sky, 'Take Care, Take Care, Take Care' 41 Paul Simon, 'So BeautiFul Or So What' 42 Yuck, 'Yuck' 43 Bjork, 'Biophilia' 44 Washed Out, 'Within And Without' 45 Real Estate, 'Days' 46 Kurt Vile, 'Smoke Ring For My Halo' 47 The Mountain Goats, 'All Eternals Deck' 48 Danger Mouse And Daniele Luppi, 'Rome' 49 The Weeknd, 'House OF Balloons' 50 R.E.M., 'Collapse Into NoW' 51 Portugal.