Contesting Power, Contesting Memories the History of the Koregaon Memorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

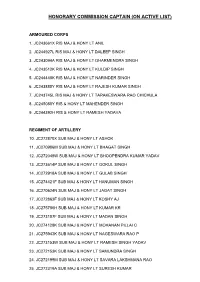

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Koyna Dam (Pic:Mh09vh0100)

DAM REHABILITATION AND IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (DRIP) Phase II (Funded by World Bank) KOYNA DAM (PIC:MH09VH0100) ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIAL DUE DILIGENCE REPORT August 2020 Office of Chief Engineer Water Resources Department PUNE Region Mumbai, Maharashtra E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Page No. Executive Summary 4 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 PROJECT OVERVIEW 6 1.2 SUB-PROJECT DESCRIPTION – KOYNA DAM 6 1.3 IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENT AND SCHEDULE 11 1.4 PURPOSE OF ESDD 11 1.5 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY OF ESDD 12 CHAPTER 2: INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK AND CAPACITY ASSESSMENT 2.1 POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK 13 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 13 CHAPTER 3: ASSESSMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS 3.1 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 15 3.2 PROTECTED AREA 16 3.3 SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT 18 3.4 CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT 19 CHAPTER 4: ACTIVITY WISE ENVIRONMENT & SOCIAL SCREENING, RISK AND IMPACTS IDENTIFICATION 4.1 SUB-PROJECT SCREENING 20 4.2 STAKEHOLDERS CONSULTATION 24 4.3 DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY OF RISKS AND IMPACTS BASED ON SCREENING 24 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS 5.1 CONCLUSIONS 26 5.1.1 Risk Classification 26 5.1.2 National Legislation and WB ESS Applicability Screening 26 5.2 RECOMMENDATIONS 27 5.2.1 Mitigation and Management of Risks and Impacts 27 5.2.2 Institutional Management, Monitoring and Reporting 28 List of Tables Table 4.1: Summary of Identified Risks/Impacts in Form SF 3 23 Table 5.1: WB ESF Standards applicable to the sub-project 26 Table 5.2: List of Mitigation Plans with responsibility and timelines 27 List of Figures Figure -

![Southern Army, India (1944-45)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8269/southern-army-india-1944-45-1088269.webp)

Southern Army, India (1944-45)]

2 October 2020 [SOUTHERN ARMY, INDIA (1944-45)] Southern Army 105 Line of Communication Area (1) 8th (Rajput) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Indian Artillery (H.Q., 21st, 22nd & 23rd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Batteries, Indian Artillery) 12th Indian Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Indian Artillery (H.Q., 33rd & 34th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Batteries, Indian Artillery) 17th Indian Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Indian Artillery (H.Q., 11th, 101st & 103rd Light Anti-Aircraft Batteries, Indian Artillery) 4th Indian Coast Regiment, Indian Artillery 26th Bn. 5th Mahratta Light Infantry 8th Bn. 14th Punjab Regiment 2nd Bn. The Sikh Light Infantry 2nd Bn. The Bihar Regiment 2nd Bn. Mysore Infantry, Indian States Forces Rajaram Infantry, Indian States Forces 3rd Bn. Hyderabad Infantry (Nizam’s Own), Indian States Forces © www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 2 October 2020 [SOUTHERN ARMY, INDIA (1944-45)] NOTES: 1. This Lines of Communication Area was formerly the Madras District, with its headquarters in the city of Madras. It was converted to a L.o.C. Area on 28 April 1942, shortly after Southern Command had become Southern Army. In November 1945, the L.o.C. Area was redesignated as the Madras Area. 2. 3. © www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 2 2 October 2020 [SOUTHERN ARMY, INDIA (1944-45)] 108 Line of Communication Area (1) 3rd Indian Coast Regiment, Indian Artillery 27th Bn. 6th Rajputana Rifles 25th Bn. 12th Frontier Force Regiment 25th Bn. 3rd Madras Regiment 25th Bn. 19th Hyderabad Regiment 25th Bn. The Mahar Regiment 25th Bn. The Ajmer Regiment 2nd Napalese Rifles, Napal Army 14th Bn. 5th Mahratta Light Infantry © www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 3 2 October 2020 [SOUTHERN ARMY, INDIA (1944-45)] NOTES: 1. -

List of Nagar Panchayat in the State of Maharashtra Sr

List of Nagar Panchayat in the state of Maharashtra Sr. No. Region Sub Region District Name of ULB Class 1 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Karjat Nagar panchayat NP 2 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Parner Nagar Panchayat NP 3 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Shirdi Nagar Panchyat NP 4 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Akole Nagar Panchayat NP 5 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Newasa Nagarpanchayat NP 6 Amravati SRO Akola Akola Barshitakli Nagar Panchayat NP 7 Amravati SRO Amravati 1 Amravati Teosa Nagar Panchayat NP 8 Amravati SRO Amravati 1 Amravati Dharni Nagar Panchayat NP 9 Amravati SRO Amravati 1 Amravati Nandgaon (K) Nagar Panchyat NP 10 Aurangabad S.R.O.Aurangabad Aurangabad Phulambri Nagar Panchayat NP 11 Aurangabad S.R.O.Aurangabad Aurangabad Soigaon Nagar Panchayat NP 12 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Ashti Nagar Panchayat NP 13 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Wadwani Nagar Panchayat NP 14 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed shirur Kasar Nagar Panchayat NP 15 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Keij Nagar Panchayat NP 16 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Patoda Nagar Panchayat NP 17 Nagpur SRO Nagpur Bhandara Mohadi Nagar Panchayat NP 18 Nagpur SRO Nagpur Bhandara Lakhani nagar Panchayat NP 19 Nagpur SRO Nagpur Bhandara Lakhandur Nagar Panchayat NP 20 Amravati SRO Akola Buldhana Sangrampur Nagar Panchayat NP 21 Amravati SRO Akola Buldhana Motala Nagar panchyat NP 22 Chandrapur SRO Chandrapur Chandrapur Saoli Nagar panchayat NP 23 Chandrapur SRO Chandrapur Chandrapur Pombhurna Nagar panchayat NP 24 Chandrapur SRO Chandrapur Chandrapur Korpana Nagar panchayat NP 25 Chandrapur -

Satara District Maharashtra

1798/DBR/2013 भारत सरकार जल संसाधन मंत्रालय कᴂ द्रीय भूजल बो셍ड GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD महाराष्ट्र रा煍य के अंत셍डत सातारा जजले की भूजल विज्ञान जानकारी GROUND WATER INFORMATION SATARA DISTRICT MAHARASHTRA By 饍िारा Abhay Nivasarkar अभय ननिसरकर Scientist-B िैज्ञाननक - ख म鵍य क्षेत्र, ना셍पुर CENTRAL REGION, NAGPUR 2013 1 SATARA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. LOCATION North latitude : 17°05’ to 18°11’ East longitude : 73°33’ to 74°54’ Normal Rainfall : 473 -6209 mm 2. GENERAL FEATURES Geographical area : 10480 sq.km. Administrative division : Talukas – 11 ; Satara , Mahabeleshwar (As on 31.3.2013) Wai, Khandala, Phaltan, Man,Jatav, Koregaon Jaoli, , Patan, Karad. Towns : 10 Villages : 1721 Watersheds : 52 3. POPULATION (2001, 2010 Census) : 28.09,000., 3003922 Male : 14.08,000, 1512524 Female : 14.01,000, 1491398 Population growth (1991-2001) : 14.59, 6.94 % Population density : 268 , 287 souls/sq.km. Literacy : 78.22 % Sex ratio : 995 (2010 Census) Normal annual rainfall : 473 mm 6209 mm (2001-2010) 4 GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Geomorphic Unit : Western Ghat, Foothill zone , Central , : Plateau and eastern plains Major Drainage : Krishna, Nira, Man 5 LAND USE (2010) Forest area : 1346 sq km Net Sown area : 6960 sq km Cultivable area : 7990 sq km 6 SOIL TYPE : 2 Medium black, Deep black 7 PRINCIPAL CROPS Jawar : 2101 sq km Bajara : 899 sq km Cereals : 942 sq km Oil seeds : 886 sq km Sugarcane : 470 sq km 8 GROUND WATERMONITORING Dugwell : 46 Piezometer : 06 9 GEOLOGY Recent : Alluvium i Upper-Cretaceous to -

MSEDCL Authority Padalkar Engineer Mail.Com Baramati Rural Circle, Urja Bhavan, II Floor, Public Information Keshav Vajanathrao Executive Sebaramati@G 1 7875768027

Baramati Zone Office,Baramati Sr. Office Name & First Appeallate Name of Assistant RTI Designation Mobile Number Email-Id No. Address officer / Public officer information officer/ Assistant Public information officer 1 Baramati Zone First Appeallate Sou. Poonam Ashish Superintending 7875768222 office officer Rokade Engineer baramati,Urjabh avan bhigwan road baramati Public information Uday Madhukar Kulkarni Executive 7875768028 officer Engineer sesatara@gmai l.com Assistant Public Dilipkumar Bajarang Deputy 7875768519 information officer Karvekar Executive Engineer Baramati Rural Circle Sr Office Name & First Appellate Name of Officer Designation in Mobile Number E-mail No Address Authority / Nodal Office Address Officer, Public Information Officer / System Administrator and Assistant Information Officer First Appellate Dattatraya Vishnu Superintending sebaramati@g 7875768111 MSEDCL Authority Padalkar Engineer mail.com Baramati Rural Circle, Urja Bhavan, II Floor, Public Information Keshav Vajanathrao Executive sebaramati@g 1 7875768027 Bhigwan road, Officer Kalumali Engineer mail.com Baramati, Pune- 413102 Assistant Information Dy Executive sebaramati@g Nilesh Ramling Borate 7875768081 Officer Engineer mail.com Baramati Division First Appellate Executive eebaramati@g Ganesh Manikrao Latpate 7875768005 Authority Engineer mail.com Baramati Division, Urjabhavan, I Public Information Dy Executive eebaramati@g 2 Floor, Bhigwan Savita Rahul Khatavkar 7875768096 Officer Engineer mail.com Road Baramati Tal : Baramati Dist : Pune Assistant Information -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

Dakhan History

DAKHAN HISTORY: MUSALMÁN AND MARÁTHA, A.D. 1300-1818. Part I, —Poona Sa'ta'ra and Shola'pur. BY W. W. LOCH ESQUIRE, BOMBAY CIVIL SERVICE. [CONTRIBUTED IN 1877,] DAKHAN HISTORY. PART I. POONA SÁTÁRA AND SHOLHÁPUR, A.D.1300-1818. Introductory. THE districts which form the subject of this article, the home of the Maráthás and the birth- place of the Marátha dynasty, streteh for about 150 miles along the Sayhádri hills between the seventeenth and nineteenth degrees of latitude, and at one point pass as far as 160 miles inland. All the great Marátha capitals, Poona Sátára and Kolhápur, lie close to the Sayhádris under the shelter of some hill fort ; while the Musalmán capitals, Ahmadnagar Bijápur Bedar and Gulbarga, are walled cities in the plain. Of little consequence under the earlier Musalmán rulers of the Dakhan; growing into importance under the kings of Bijápur and Ahmadnagar ; rising with the rise of the state, the foundations of which Shiváji laid in the seventeenth century, these districts became in the eighteenth century the seat of an empire reaching from the Panjáb to the confines of Bengal and from Delhi to Mysor. Early History. Early in the Christian era Maháráshtra is said to have been ruled by the great Saliváhana, whose capital was at Paithán on the Godávari. At a later period a powerful dynasty of Chálukya Rájputs reigned over a large part of Maháráshtra and the Karnátak, with a capital at Kalyán, 200 miles north-west of Sholápur. The Chálukyas reached their greatest power under Tálapa Deva in the tenth century, and became extinct about the end of the twelfth century, when the Jádhav or Yádav rájás of Devgiri or Daulatábád became supreme. -

History 2020-21

History (PRE-Cure) April 2020 - March 2021 Visit our website www.sleepyclasses.com or our YouTube channel for entire GS Course FREE of cost Also Available: Prelims Crash Course || Prelims Test Series T.me/SleepyClasses Table of Contents Links to the videos on YouTube .................1 29.Constitution day .....................................28 1. Services Day ......................................2 30.Lingayats ..................................................28 2. Indian Civil Services ........................2 31.Guru Nanak Dev Ji .................................29 3. Harijan Sevak Sangh celebrates its 32.Annapurna Statue to come back to India foundation day .........................................4 30 4. COVID-19 infection spreads to vulnerable 33.Mahaparinirvana Diwas ......................31 tribal community in Odisha ..................4 34.Cattle, buffalo meat residue found in 5. Tata group to construct India's new Indus Valley vessels .................................33 parliament building. ................................5 35.Tharu Tribals ...........................................34 6. Onam .........................................................6 36.Hampi stone chariot now gets protective 7. Kala Sanskriti Vikas Yojana (KSVY) ..6 ring ...............................................................35 8. Tech for Tribals ........................................7 37.Gwalior, Orchha in UNESCO world 9. Chardham Project ..................................8 heritage cities list: MP Govt ..................36 10.Rare inscription