Circling Chase the Art and Inf Luence of William Merritt Chase and the Pursuit of Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illustrations of Selected Works in the Various National Sections of The

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION libraries 390880106856C A«T FALACr CttNTRAL. MVIIION "«VTH rinKT OFFICIAI ILLUSTRATIONS OF SELECTED WORKS IN THE VARIOUS NATIONAL SECTIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ART WITH COMPLETE LIST OF AWARDS BY THE INTERNATIONAL JURY UNIVERSAL EXPOSITION ST. LOUIS, 1904 WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HALSEY C. IVES, CHIEF OF THE DEPARTMENT DESCRIPTIVE TEXT FOR PAINTINGS BY CHARLES M. KURTZ, Ph.D., ASSISTANT CHIEF DESCRIPTIVE TEXT FOR SCULPTURES BY GEORGE JULIAN ZOLNAY, superintendent of sculpture division Copyr igh r. 1904 BY THE LOUISIANA PURCHASE EXPOSITION COMPANY FOR THE OFFICIAL CATALOGUE COMPANY EXECUTIVE OFFICERS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ART Department ' B’’ of the Division of Exhibits, FREDERICK J. V. SKIFF, Director of Exhibits. HALSEY C. IVES, Chief. CHARLES M. KURTZ, Assistant Chief. GEORGE JULIAN ZOLNAY, Superintendent of the Division of Sculpture. GEORGE CORLISS, Superintendent of Exhibit Records. FREDERIC ALLEN WHITING, Superintendent of the Division of Applied Arts. WILL H. LOW, Superintendent of the Loan Division. WILLIAM HENRY FOX Secretary. INTRODUCTION BY Halsey C. Ives “All passes; art alone enduring stays to us; I lie bust outlasts the throne^ the coin, Tiberius.” A I an early day after the opening of the Exposition, it became evident that there was a large class of visitors made up of students, teachers and others, who desired a more extensive and intimate knowledge of individual works than could be gained from a cursory view, guided by a conventional catalogue. 11 undreds of letters from persons especially interested in acquiring intimate knowledge of the leading char¬ acteristics of the various schools of expression repre¬ sented have been received; indeed, for two months be¬ fore the opening of the department, every mail carried replies to such letters, giving outlines of study, courses of reading, and advice to intending visitors. -

Finding Aid for the John Sloan Manuscript Collection

John Sloan Manuscript Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum The John Sloan Manuscript Collection is made possible in part through funding of the Henry Luce Foundation, Inc., 1998 Acquisition Information Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978 Extent 238 linear feet Access Restrictions Unrestricted Processed Sarena Deglin and Eileen Myer Sklar, 2002 Contact Information Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives Delaware Art Museum 2301 Kentmere Parkway Wilmington, DE 19806 (302) 571-9590 [email protected] Preferred Citation John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Related Materials Letters from John Sloan to Will and Selma Shuster, undated and 1921-1947 1 Table of Contents Chronology of John Sloan Scope and Contents Note Organization of the Collection Description of the Collection Chronology of John Sloan 1871 Born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania on August 2nd to James Dixon and Henrietta Ireland Sloan. 1876 Family moved to Germantown, later to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1884 Attended Philadelphia's Central High School where he was classmates with William Glackens and Albert C. Barnes. 1887 April: Left high school to work at Porter and Coates, dealer in books and fine prints. 1888 Taught himself to etch with The Etcher's Handbook by Philip Gilbert Hamerton. 1890 Began work for A. Edward Newton designing novelties, calendars, etc. Joined night freehand drawing class at the Spring Garden Institute. First painting, Self Portrait. 1891 Left Newton and began work as a free-lance artist doing novelties, advertisements, lettering certificates and diplomas. 1892 Began work in the art department of the Philadelphia Inquirer. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture

COVERFEATURE THE PAAMPROVINCETOWN ART ASSOCIATION AND MUSEUM 2014 A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture By Christopher Busa Certainly it is impossible to capture in a few pages a century of creative activity, with all the long hours in the studio, caught between doubt and decision, that hundreds of artists of the area have devoted to making art, but we can isolate some crucial directions, key figures, and salient issues that motivate artists to make art. We can also show why Provincetown has been sought out by so many of the nation’s notable artists, performers, and writers as a gathering place for creative activity. At the center of this activity, the Provincetown Art Associ- ation, before it became an accredited museum, orga- nized the solitary efforts of artists in their studios to share their work with an appreciative pub- lic, offering the dynamic back-and-forth that pushes achievement into social validation. Without this audience, artists suffer from lack of recognition. Perhaps personal stories are the best way to describe PAAM’s immense contribution, since people have always been the true life source of this iconic institution. 40 PROVINCETOWNARTS 2014 ABOVE: (LEFT) PAAM IN 2014 PHOTO BY JAMES ZIMMERMAN, (righT) PAA IN 1950 PHOTO BY GEORGE YATER OPPOSITE PAGE: (LEFT) LUCY L’ENGLE (1889–1978) AND AGNES WEINRICH (1873–1946), 1933 MODERN EXHIBITION CATALOGUE COVER (PAA), 8.5 BY 5.5 INCHES PAAM ARCHIVES (righT) CHARLES W. HAwtHORNE (1872–1930), THE ARTIST’S PALEttE GIFT OF ANTOINETTE SCUDDER The Armory Show, introducing Modernism to America, ignited an angry dialogue between conservatives and Modernists. -

American Impressionism Treasures from the Daywood Collection

American Impressionism Treasures from the Daywood Collection American Impressionism: Treasures from the Daywood Collection | 1 Traveling Exhibition Service The Art of Patronage American Paintings from the Daywood Collection merican Impressionism: Treasures from the Daywood dealers of the time, such as Macbeth Gallery in New York. Collection presents forty-one American paintings In 1951, three years after Arthur’s death, Ruth Dayton opened A from the Huntington Museum of Art in West Virginia. the Daywood Art Gallery in Lewisburg, West Virginia, as a The Daywood Collection is named for its original owners, memorial to her late husband and his lifelong pursuit of great Arthur Dayton and Ruth Woods Dayton (whose family works of art. In doing so, she spoke of her desire to “give surnames combine to form the moniker “Daywood”), joy” to visitors by sharing the collection she and Arthur had prominent West Virginia art collectors who in the early built with such diligence and passion over thirty years. In twentieth century amassed over 200 works of art, 80 of them 1966, to ensure that the collection would remain intact and oil paintings. Born into wealthy, socially prominent families on public display even after her own death, Mrs. Dayton and raised with a strong appreciation for the arts, Arthur and deeded the majority of the works in the Daywood Art Gallery Ruth were aficionados of fine paintings who shared a special to the Huntington Museum of Art, West Virginia’s largest admiration for American artists. Their pleasure in collecting art museum. A substantial gift of funds from the Doherty only increased after they married in 1916. -

Bringing to Light Theodore Wendel (1857-1932) (Left)Rose Arbor, Circa 1905-1915 Oil on Canvas Mounted to Wood Panel 1 1 30 ⁄2 X 21 ⁄8 Inches Signed Lower Right: Theo

Bringing to Light Theodore Wendel (1857-1932) (left)Rose Arbor, circa 1905-1915 Oil on canvas mounted to wood panel 1 1 30 ⁄2 x 21 ⁄8 inches Signed lower right: Theo. Wendel (front cover, detail) Moonrise on the Farm, pg. 9 Bringing to Light: Theodore Wendel (1857-1932) October 19th - December 7th, 2019 V OSE G ALLER IES An Unsung Impressionist By Courtney S. Kopplin For generations, Vose Galleries has welcomed the opportunity to shine a light on the work of ‘unsung artists’ throughout art history, and in the sphere of American Impressionism there is perhaps no artist more deserving of this attention than Theodore Wendel. As part of the first wave of Americans to visit Giverny in the summer of 1887, joining John Leslie Breck, Willard Metcalf and Theodore Robinson, Wendel became one of the earliest painters to apply impressionist principles to his plein air interpretations of the French countryside; sources later reported that the master himself, Claude Monet, who limited his interactions with the Americans, thought highly of Wendel’s work. In March of 1889, short- ly after settling in Boston, Wendel organized a three-day viewing of his pastoral landscapes at a studio on Boylston Street, coinciding with Met- calf’s exhibition of foreign paintings held nearby at the St. Botolph Club. Theodore Wendel painting daughter Mary, Both artists garnered positive reviews from the local press, and over the Upper Farm, Ipswich, circa 1915 next several years Wendel maintained an active exhibition schedule, including a two-person show with Theodore Robinson in 1892, featu- provided, combined with his steady roster of exhibitions, allowed Wen- ring both oils and pastels; several solo and group shows with his fellow del to feel more financially secure in his profession and in 1897 he and Boston artists at the St. -

ACH Payments File Upload Reference Guide (PDF)

ACH Payments File Upload Reference Guide Learn how to import a file to make ACH payments using Chase for Business or Chase Connect. MARCH 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS FILE SPECIFICATIONS............................................................................................................................ 4 FILE HEADER RECORD (1) ......................................................................................................................... 5 BATCH HEADER RECORD (5) .................................................................................................................... 5 ENTRY DETAIL RECORD (6) ....................................................................................................................... 7 ADDENDA RECORD (7)* ........................................................................................................................... 8 BATCH CONTROL RECORD (8) .................................................................................................................. 9 FILE CONTROL RECORD (9)..................................................................................................................... 10 SUPPORT FOR CHASE FOR BUSINESS & CHASE CONNECT ................................................................... 11 About the file upload service ............................................................................................................. 11 Important things you need to know .............................................................................................. -

ACH Payments CSV File Upload Reference Guide

ACH Payments CSV File Upload Reference Guide Learn how to import a file for ACH payments using Chase for Business or Chase Connect. March 2019 Last Modified: March 17, 2019 This guide is confidential and proprietary to J.P. Morgan and is provided for your general information only. It is subject to change without notice and is not intended to be legally binding. All services described in this guide are subject to applicable laws and regulations and service terms. Not all products and services are available in all locations. Eligibility for particular products and services will be determined by JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. or its affiliates. J.P. Morgan makes no representation as to the legal, regulatory or tax implications of the matters referred to in this guide. J.P. Morgan is a marketing name for the Treasury Services businesses of JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., member FDIC, and its affiliates worldwide. ©2019 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights reserved. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS File specification ................................................................................................................................... 5 File information row (1).................................................................................................................... 7 Batch information row (5) ................................................................................................................ 8 Payment detail row (6) ..................................................................................................................... 9 -

Choosing Right Typeface Means Cash for Your Cause

FUNDRAISING forum Choosing the Right Type Translates into Cash for Your Cause Don’t leave it to chance. Your choice of typeface will affect your bottom line. BY THOMAS K. KELLER “I’ve got bigger fish to fry,” thinks a Few charities have a universe large Bodoni—have become classics. They charity administrator when asked if the enough to do such extensive testing. So work. In the world of typography, they’re typeface used in a fundraising piece is they may want to look at what the DAV the survivors of the evolutionary process. okay. “Besides, this is basic stuff. Surely has learned. (This article, by the way, is set in the graphics people know what works Century.) best.” To Serif or Not to Serif: Those faces are also very expressive. That’s the Big Question They have personality. Their forms, Does It Really shapes, and letter heights can support a Make a Difference? With the DAV’s enthusiasm for mar- message in clear, understandable ways. ket research, it’s no surprise that this Century Schoolbook has an elegant sim- If the final printed piece looks good, large charity ignored graphics profession- plicity that has seldom been matched, an how much difference can the choice of als’ pontification concerning serif vs. elegance that Goudy takes a step further. one typeface over another really make? sanserif type. Instead, the organization What about the dignified presence of The difference was half a million dollars subjected the controversy to market test- Bookman, or the fundamental work-a-day in a recent nationwide test mailing done ing. -

ELECTRICAL SPECIFICATIONS for BROWNSVILLE PUB WATER PURIFICATION PLANT LIGHTING PROJECT September 13, 2020 Juan-Pablo Cantu, P

ELECTRICAL SPECIFICATIONS for BROWNSVILLE PUB WATER PURIFICATION PLANT LIGHTING PROJECT September 13, 2020 The Seal appearing on this Document was authorized by Juan-Pablo Cantu, PE, #90105 On 9/13/2020 Juan-Pablo Cantu, P.E. Square E Engineering 32238 Whipple Rd. Los Fresnos TX, 78566 Firm # F-12247 SECTION 16000 GENERAL ELECTRICAL SPECIFICATIONS ELECTRICAL PART 1: GENERAL SCOPE OF WORK: Furnish and install complete LIGHTING system for the BPUB WTP#2 Water Purification Plant Lighting Project. Scope of work shall include Furnishing and Installation of a complete Electrical equipment and materials for a fully operational and functional system including all conduit and wiring; conduit fittings; conduit support system; Improvements to Low Voltage Panels, Supporting rack and existing Electrical Panels, and Lighting Control system all required equipment for a complete and working lighting system as detailed in these plans and specifications. 1.01 GENERAL The General Conditions and Requirements, Special Provisions, if applicable are hereby made a part of this section. A. The Electrical Drawings and Specifications under this section shall be made a part of the contract documents. The Drawings and specifications of this contract, as well as supplements issued thereto, information to bidders and pertinent documents issued by the Owner's representative are a part of these drawings and specifications and shall be complied with in every respect. All of the above documents will be on file at the Owner's office and shall be examined by all bidders. Failure to examine all documents shall not relieve this responsibility or be used as a basis for additional compensation due to omission of details of other sections from the electrical documents. -

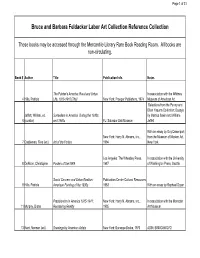

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S.