Water Course Philippines 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balesin Island Club

BALESIN ISLAND CLUB It’s easy to say nice things about yourself, but what matters is what others say about you. Here is what others have said about Balesin. July/August 2010 Balesin beckons oberto Ongpin waxes lyrical when Balesin presents that interesting involves initially the development of R he talks about Balesin, a 500- hectare opportunity and he is determined to six themed villages based on Ongpin’s white-sand island off the coast of make it a stand-out. Ongpin reckons own travels – Mykonos (Greece), Quezon province on the Philippines’ that if he did not enter the world of Sardinia (Italy), St. Tropez (France), Pacific coast. Alphaland, the listed company business, he would probably have been Phuket (Thailand), Bali (Indonesia) Ongpin runs with investment from UK- an architect. “There were 11 architects and a still unnamed Philippine island based Ashmore group, had acquired the involved in the development of the initial theme. Each village will have 20 to property recently from the family of phase of Tagaytay Highlands; one of 30 units. Work has started on a new the late Edgardo Tordesillas, who was them is unlicensed,” he chuckles. He runway. Alphaland will be acquiring Ongpin’s deputy at the trade and industry says that some of the greatest battles small aircrafts for the 25-minute hop ministry when both of them were in he had then was often over design – the to ferry vacationers to the island. By government in the 1980s. Part of Ongpin’s look and feel. He believes in building to the end of the year, Ongpin hopes excitement is explained by the fact that cater to the high end of the market – to to have the clubhouse up and running. -

Assumption Parking Lot Rosary.Pub

Thank you for joining in this celebration Please of the Blessed Mother and our Catholic park in a faith. Please observe these guidelines: designated Social distancing rules are in effect. Please maintain 6 feet distance from everyone not riding parking with you in your vehicle. You are welcome to stay in your car or to stand/ sit outside your car to pray with us. space. Anyone wishing to place their own flowers before the statue of the Blessed Mother and Christ Child may do so aer the prayers have concluded, but social distancing must be observed at all mes. Please present your flowers, make a short prayer, and then return to your car so that the next person may do so, and so on. If you wish to speak with others, please remember to wear a mask and to observe 6 foot social distancing guidelines. Opening Hymn—Hail, Holy Queen Hail, holy Queen enthroned above; O Maria! Hail mother of mercy and of love, O Maria! Triumph, all ye cherubim, Sing with us, ye seraphim! Heav’n and earth resound the hymn: Salve, salve, salve, Regina! Our life, our sweetness here below, O Maria! Our hope in sorrow and in woe, O Maria! Sign of the Cross The Apostles' Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Ponus Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. -

Bird List Column A: We Should Encounter (At Least a 90% Chance) Column B: May Encounter (About a 50%-90% Chance) Column C: Possible, but Unlikely (20% – 50% Chance)

THE PHILIPPINES Prospective Bird List Column A: we should encounter (at least a 90% chance) Column B: may encounter (about a 50%-90% chance) Column C: possible, but unlikely (20% – 50% chance) A B C Philippine Megapode (Tabon Scrubfowl) X Megapodius cumingii King Quail X Coturnix chinensis Red Junglefowl X Gallus gallus Palawan Peacock-Pheasant X Polyplectron emphanum Wandering Whistling Duck X Dendrocygna arcuata Eastern Spot-billed Duck X Anas zonorhyncha Philippine Duck X Anas luzonica Garganey X Anas querquedula Little Egret X Egretta garzetta Chinese Egret X Egretta eulophotes Eastern Reef Egret X Egretta sacra Grey Heron X Ardea cinerea Great-billed Heron X Ardea sumatrana Purple Heron X Ardea purpurea Great Egret X Ardea alba Intermediate Egret X Ardea intermedia Cattle Egret X Ardea ibis Javan Pond-Heron X Ardeola speciosa Striated Heron X Butorides striatus Yellow Bittern X Ixobrychus sinensis Von Schrenck's Bittern X Ixobrychus eurhythmus Cinnamon Bittern X Ixobrychus cinnamomeus Black Bittern X Ixobrychus flavicollis Black-crowned Night-Heron X Nycticorax nycticorax Western Osprey X Pandion haliaetus Oriental Honey-Buzzard X Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard X Pernis celebensis Black-winged Kite X Elanus caeruleus Brahminy Kite X Haliastur indus White-bellied Sea-Eagle X Haliaeetus leucogaster Grey-headed Fish-Eagle X Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

2005 Annual Regional Economic Situationer (ARES)

. CAGAYAN VALLEY ANNUAL REGIONAL ECONOMIC SITUATIONER (ARES) 2005 ASSESSMENT OF ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE Economic adversities and natural calamities pulled back the economic performance of Region 02 in the year 2005 as all the major sectors of the regional economy registered setbacks. Specifically, the decreases were recorded in agricultural production, tourism, air transport industry, and investments generated. The prolonged dry spell coupled with floods brought by typhoon “Labuyo” exacted a heavy toll on agriculture sector. While there were government measures implemented to boost production of palay, corn and other crops such as the usage of high-yielding and certified seeds, this was not enough to restrain the impact of the fortuitous weather conditions occurring in the region. Nonetheless, fishery production stepped up by 9.34 percent owing to the improvements in municipal fishing and significant gains in aquaculture. As a consequence of these natural calamities and the VAT law, inflation rate in the region went up to 6.88 percent. Inflation rate on food items increased as the weather took its toll on the supplies of these commodities. Likewise, prices of dairy products went up pulled by the implementation of the VAT which directly affects this type of food groups (processed and canned goods). The rise in the crude oil prices and the implementation of VAT, led also to the increases in transport fares, water and electricity tariffs. Related to the slide in agricultural production and increase in prices, investments generated in the region reflected a dormant performance as it barely grew by 0.86 percent. This decline was evident in all the three sectors, the Services sector having the biggest number of workers laid off during the year. -

![Use of Field Recorded Sounds in the Assessment of Forest Birds in Palawan, Philippines ______Required in the Field [19]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0725/use-of-field-recorded-sounds-in-the-assessment-of-forest-birds-in-palawan-philippines-required-in-the-field-19-570725.webp)

Use of Field Recorded Sounds in the Assessment of Forest Birds in Palawan, Philippines ______Required in the Field [19]

Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, Vol. 7, No. 2, May, 2019 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Asia Pacific Journal of Use of Field Recorded Sounds in the Multidisciplinary Research Assessment of Forest Birds in Palawan, Vol. 7 No.2, 24-31 May 2019 Philippines P-ISSN 2350-7756 E-ISSN 2350-8442 Alejandro A. Bernardo Jr. www.apjmr.com College of Arts and Sciences, Western Philippines University, CHED Recognized Journal Aborlan, Palawan, Philippines ASEAN Citation Index [email protected] Date Received: August 3, 2018; Date Revised: February 8, 2019 Abstract -The uses of bioacoustics in biological applications are getting popular in research communities. Among such application is the use of sound recordings in avifaunal researches. This research explored the possibility of using the sound recording in the assessment of forest birds in Palawan by comparing it in widely used Point Count Method (PCM). To compare the two methods, a simultaneous point count and sound recording surveys from February to November 2017 in the forested slopes of Victoria-Anipahan Mountain in Aborlan, Palawan were conducted. The Sound Recording Method (SRM) listed slightly lower species richness than the PCM, but the difference in the mean number of species was not significant (F1,49=1.05, p > 0.05). The SRM was found to be biased towards noisy and loud calling bird species but it failed to detect the silent and rarely calling species. SRM was also equally sensitive as compared to PCM in detecting endemic and high conservation priority species. Because of these, it was recognized that SRM could be used as one of the alternative methods in forest bird assessment particularly if the concern is avifaunal species richness. -

Or Negros Oriental

CITY CANLAON CITY LAKE BALINSASAYAO KANLAON VOLCANO VALLEHERMOSO Sibulan - The two inland bodies of Canlaon City - is the most imposing water amid lush tropical forests, with landmark in Negros Island and one of dense canopies, cool and refreshing the most active volcanoes in the air, crystal clear mineral waters with Philippines. At 2,435 meters above sea brushes and grasses in all hues of level, Mt. Kanlaon has the highest peak in Central Philippines. green. Balinsasayaw and Danao are GUIHULNGAN CITY 1,000 meters above sea level and are located 20 kilometers west of the LA LIBERTAD municipality of Sibulan. JIMALALUD TAYASAN AYUNGON MABINAY BINDOY MANJUYOD BAIS CITY TANJAY OLDEST TREE BAYAWAN CITY AMLAN Canlaon City - reportedly the oldest BASAY tree in the Philipines, this huge PAMPLONA SAN JOSE balete tree is estimated to be more NILUDHAN FALLS than a thousand years old. SIBULAN Sitio Niludhan, Barangay Dawis, STA. CATALINA DUMAGUETE Bayawan City - this towering cascade is CITY located near a main road. TAÑON STRAIT BACONG ZAMBOANGUITA Bais City - Bais is popular for its - dolphin and whale-watching activities. The months of May and September are ideal months SIATON for this activity where one can get a one-of-a kind experience PANDALIHAN CAVE with the sea’s very friendly and intelligent creatures. Mabinay - One of the hundred listed caves in Mabinay, it has huge caverns, where stalactites and stalagmites APO ISLAND abound. The cave is accessible by foot and has Dauin - An internationally- an open ceiling at the opposite acclaimed dive site with end. spectacular coral gardens and a cornucopia of marine life; accessible by pumpboat from Zamboanguita. -

St. Lorenzo Ruiz Catholic Parish Community

St. Lorenzo Ruiz Catholic Parish Community “Where Earth meets Heaven” Our Mission Statement As a welcoming community, we celebrate our life, conscious of our multi-ethnic traditions, vowing unity with Christ in our multi-cultural differences. We usher in our lives (being evangelized) and proclaim (as evangelizers) the reign of God as Priests, Prophets and Kings, and in so doing, we celebrate our discipleship in Christ Jesus. We extol “being Church” through the formation of Small Faith Communities as a way of life in being priests, prophets and kings; thus, we become economically stable and self-reliant as we give special attention and solicitude to our youth and the needy. “They were faithful to the teaching of the apostles, the common life of sharing, the breaking of bread and the prayers.” (Acts 2:42) A message from Fr. Tony St. Lorenzo Ruiz Catholic Parish Community “Where Earth meets Heaven” To our dear servant leaders, 747 Meadowpass Road I join the Apostle Paul and his letter to the Philippians: “I Walnut CA 91789 Phone (909) 595-9545 thank God whenever I think of you and everytime I pray Fax (909) 594-3940 for you all, I always pray with joy…” Phil 1:3 www.saintlorenzo.org Thank you, thank you and I cannot thank you enough on behalf of our community for serving as servant leaders for Rev. Tony P. Astudillo at least a couple of years. It is my sincerest hope that as Pastor you shared your time, talent and treasure with us as Rev. Elmer S. Empinado servants, your position/responsibility has been rewarding Associate Pastor to you as well. -

Naujan Lake National Park Site Assessment Profile

NAUJAN LAKE NATIONAL PARK SITE ASSESSMENT AND PROFILE UPDATING Ireneo L. Lit, Jr., Sheryl A. Yap, Phillip A. Alviola, Bonifacio V. Labatos, Marian P. de Leon, Edwino S. Fernando, Nathaniel C. Bantayan, Elsa P. Santos and Ivy Amor F. Lambio This publication has been made possible with funding support from Malampaya Joint Ventures Partners, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Provincial Government of Oriental Mindoro and Provincial Government of Occidental Mindoro. i Copyright: © Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Inc. All rights reserved: Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes, in any form or by any means, is prohibited without the express written permission from the publisher. Recommended Citation: Lit Jr, I.L. Yap, S.A. Alviola, P.A. Labatos, B.V. de Leon, M.P. Fernando, S.P. Bantayan, N.C. Santos, E.P. Lambio, I.A.F. (2011). Naujan Lake National Park Site Assessment and Profile Updating. Muntinlupa City. Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Inc. ISBN 978-621-8010-04-8 Published by: Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Inc. Manila Office 22F Asian Star Building, ASEAN Drive Filinvest Corporate City, Alabang, Muntilupa City, 1780 Philippines Telephone: +63 2 8502188 Fax: +63 2 8099447 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.mbcfi.org.ph Provincial Office Gozar Street, Barangay Camilmil, Calapan City, Oriental Mindoro, 5200 Philippines Telephone/Fax: +63 43 2882326 ii NAUJAN LAKE NATIONAL PARK SITE ASSESSMENT AND PROFILE UPDATING TEAM Project Leader Ireneo L. Lit, Jr., Ph.D. Floral survey team Study Leader Edwino S. Fernando, Ph.D. Ivy Amor F. Lambio, M.Sc. Field Technician(s) Dennis E. -

Kare-Kare Santa Rosa, Wieder Auf Selbigen

198 Zentral-Luzon (Gemüse, P145), Adobo (P200), Kare-Kare Santa Rosa, wieder auf selbigen. Siehe auch (P255) und Sinigang (P220). Karte Nueva Ecija auf Seite 190. Calle Dos , Maharlika Highway/Ecke Gabaldon Street (im Melanio’s Building). Nettes Bistro mit Von Angeles entsprechender Speisekarte (Salat P125, Pasta Van: Ab Dau, neben dem Mabalacat Busterminal P160, Rib Eye Steak P240). (1½ Std.). Anreise/Weiterreise Von Baler n Mit dem Bus: Cabanatuan City Central Ter mi - Bus/Van: Mit EJ Liner, D’Liner und Maria Aurora o z nal an der Circumferential Road, 1½ km südlich Express (4 Std.). Vans benötigen 3 Std. Genesis u L vom Zentrum. Tricycle P20. Transport-Busse nach Manila fahren über Ca ba - - l a natuan. r t Für Selbstfahrer: Der 10 km lange Vergara n e High way führt in einem großen Bogen westlich Von Banaue Z um Cabanatuan herum. Er zweigt 5 km nördlich, Bus: Mit Ohayami Trans (6 Std.). Fahrtziel ist nahe Pinagpanaan, vom Maharlika Highway ab Ma nila. Ankunft in Cabanatuan erst nach Mitter - und trifft südlich von Cabanatuan, etwa 3 km vor nacht, daher vielleicht besser am Morgen zu- Cabanatuan, Baler 199 nächst mit einem Bus oder Jeepney nach Ba ga - gedreht. Nach Abschluß der Dreharbeiten über - bag oder Solano fahren und dort in einen der ließ die Filmcrew die Surfboards den Jugend li - zahlreichen Busse mit Ziel Manila umsteigen. chen von Baler und weckte dadurch ihre Begei - sterung für das Wellenreiten. Seither gilt der Ort Von Manila als Wiege des Surfens auf den Philippinen. Bus: Mit Baliwag Transit, Five Star (wenige Ab - Von der beschaulichen kleinen Baler Church im fahrten) und Genesis Transport ab deren Cubao Zentrum der Stadt führen Fußstapfen im Zement Terminal (3 Std.). -

Lepeostegeres Cebuensis (Loranthaceae), a New Mistletoe Species from Cebu, Philippines

Phytotaxa 266 (1): 048–052 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.266.1.8 Lepeostegeres cebuensis (Loranthaceae), a new mistletoe species from Cebu, Philippines PIETER B. PELSER1*, DANIEL L. NICKRENT2, ANDREW R. T. REINTAR3 & JULIE F. BARCELONA1 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand 2Department of Plant Biology, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 1125 Lincoln Drive, Carbondale, IL 62901-6509, USA 3Philippines Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Inc., Bacolod office, South Capitol Road, Bacolod City 6100, Negros Occidental, Philippines * Author for correspondence. E-mail: [email protected] Lepeostegeres cebuensis is described as a new species from Cebu Island, Philippines. It is unique among currently known species in the genus by having peculiar ridges of orange-brown scales on the young leaves and internodes. This discovery brings the total number of Philippine Lepeostegeres species to three. We consider Lepeostegeres cebuensis to be Data Defi- cient (DD) following the Red List Criteria of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Key words: Alcoy, Nug-as forest, parasitic plant, south Cebu, taxonomy Introduction Lepeostegeres Blume in Schultes & Schultes (1830: 1731; Loranthaceae) is a small mistletoe genus of nine species. It is endemic to Southeast Asia, from Peninsular Malaysia -

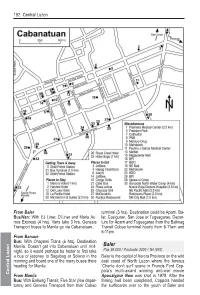

From Baler Bus/Van: with EJ Liner, D'liner and Maria Au

192 Central Luzon From Baler terminal (3 hrs). Destination could be Aparri, Ba - Bus/Van: With EJ Liner, D’Liner and Maria Au - ler, Casiguran, San Jose or Tuguegarao. De par - rora Express (4 hrs). Vans take 3 hrs. Genesis ture for Aparri and Tuguegarao from the Baliwag Transport buses to Manila go via Cabanatuan. Transit Cubao terminal hourly from 6-11am and 6-11pm. From Banaue Bus: With Ohayami Trans (6 hrs). Destination n Manila. Doesn’t get into Cabanatuan until mid - Baler o Pop 36,000 / Postcode 3200 / Tel (042) z night, so it would perhaps be better to first take u L a bus or jeepney to Bagabag or Solano in the Baler is the capital of Aurora Province on the wild l a morn ing and board one of the many buses there east coast of North Luzon where the famous r t heading for Manila. ‘Charlie don’t surf’ scene in Francis Ford Cop - n e pola’s multi-award winning anti-war movie C From Manila Apocalypse Now was shot in 1978. After the Bus: With Baliwag Transit, Five Star (few depar - filming had been completed, Coppola handed tures) an d Genesi s Transpor t fro m thei r Cubao the surfboards over to the youth of Baler and Cabanatuan, Baler 193 single-handedly started a surfing craze. Since pine Surfing Circuit season opens on the dark then, this place has been known as the cradle of sandy beach at Sabang with the three-day com - surfing in the Philippines. petition for the Aurora Surfing Cup , further From the peaceful little Baler Church in the cen - events taking place in Catanduanes, La Union, tre of the town, footsteps in cement lead to the Mindanao (Siargao Island and Surigao del Sur) nearby Doña Aurora House , a model of the and Samar.