Observing Protest from a Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black Chalk, with Traces of Red Chalk, and Framing Lines in Brown Ink

Jacob Adriaensz. BACKER (Harlingen 1608 - Amsterdam 1651) A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black chalk, with traces of red chalk, and framing lines in brown ink. Signed Backer. at the lower right. 168 x 182 mm. (6 5/8 x 7 1/8 in.) This charming drawing is a preparatory study for the pointing child at the extreme left of Jacob Backer’s Family Portrait with Christ Blessing the Children, a painting datable to c.1633-1634. This large canvas was unknown before its first appearance at auction in London in 1974, and is today in a private collection. The present sheet is drawn with a vivacity and a freedom in the application of the chalk that is stylistically indebted to Rembrandt’s chalk drawings of the same period, namely the early 1630s. Drawings executed in black chalk alone are rare in Backer’s oeuvre, but this drawing may be compared in particular to a signed and dated Self-Portrait in black chalk by Backer of 1638, in the Albertina in Vienna. A black chalk study of A Man in a Turban, in the Boijmans-van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, may also be likened to the present sheet. Provenance: Probably by descent to the artists’s brother, Tjerk Adriaensz. Backer, Amsterdam Iohan Quirijn van Regteren Altena, Amsterdam (his posthumous sale stamp [Lugt 4617] stamped on the backing sheet) Thence by descent. Literature: Werner Sumowski, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, Vol.I, New York, 1979, pp.20-21, no.3 (where dated to the mid-1630s), and also pp.46-47, under nos.16x and 17x, p.52, under no.19x and p.54, under no.20x; Werner Sumowksi, Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler, Landau/Pfalz, 1983, Vol.I, p.203, under no.72; Peter van den Brink, ‘Uitmuntend Schilder in het Groot: De schilder en tekenaar Jacob Adriansz. -

Betrachtungen Zur Sammlung

Valentina Vlasic Fokus Flinck Es ist fünfzig Jahre her, dass die letzte monographische Ausstellung den war, vorwegnahm – nämlich von seinem Freund, dem großen des barocken Malers Govert Flinck (1615-1660) stattgefunden hat. Wie niederländischen Nationaldichter Joost van den Vondel, mit dem „Reflecting History“ heute kam auch sie in seiner Geburtsstadt Kleve sagenumwobenen griechischen Künstler gleichgesetzt zu werden. zustande, und wurde vom Archivar und ersten Museumsleiter Fried- rich Gorissen (1912-1993) aus Anlass eines Jubiläums – damals des 350. Klever Sammlung Es ist ein großer Verdienst Friedrich Gorissens, Geburtstags von Flinck – organisiert. Sie fand im damaligen Städti- dass zahlreiche der historischen Besonderheiten Kleves für seine Fokus Flinck: Betrachtungen zur schen Museum Haus Koekkoek (heute Stiftung B.C. Koekkoek-Haus) Bürger und für die Nachwelt sichtbar sind. Mit seiner umsichti- statt, das 1957 gegründet und drei Jahre später eröffnet worden war. gen Forschungs- und Sammlungstätigkeit – u.a. den Werken nie- Sammlungsgeschichte, Die Ausstellung über Flinck war vom 4. Juli bis 26. September 1965 derrheinischer mittelalterlicher Bildschnitzer gewidmet, der Kunst zu sehen und es wurden – nicht unähnlich wie heute – 47 Gemälde des Barock am Klever Hof des Statthalters Johann Moritz von Nas- zum Werk und zur Ausstellung und 26 Zeichnungen aus aller Herren Länder präsentiert. Darunter sau-Siegen und der romantischen Klever Malerschule rund um Ba- befanden sich sowohl biblisch-mythologische Szenen wie Jakob er- rend Cornelis Koekkoek – legte er den Grundstein für das Klever hält Josephs blutigen Mantel (Kat. Nr. 22) und Salomo bittet um Weisheit Museum, das später von Guido de Werd umfassend ausgebaut wor- (Kat. Nr. 27) als auch Porträts wie Rembrandt als Hirte (Kat. -

Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape

Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a 1654 Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an oil on canvas Arcadian Landscape 139 x 170 cm signed and dated lower left: “G flinck. f. 1654 Govaert Flinck (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) (?)” GF-101 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape Page 2 of 11 How to cite Yeager-Crasselt, Lara. “Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape” (2018). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/elegant-shepherdess-listening-to-a- shepherd-playing-the-recorder-in-an-arcadian-landscape/ (accessed September 30, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape Page 3 of 11 Govaert Flinck’s depiction of an amorous shepherd and shepherdess in the Comparative Figures warm, evening light of a rolling landscape captures the lyrical character of the Dutch pastoral tradition.[1] The shepherd, dressed in a burnt umber robe, calf-high sandals, and a floppy brown hat, plays a recorder as he gazes longingly at the shepherdess seated beside him.[2] She returns her lover’s gaze with a coy, sideways glance, while placing a rose on her garland of flowers. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3Rd Ed

Govaert Flinck (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Govaert Flinck” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/govaert- flinck/ (accessed September 27, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Govaert Flinck Page 2 of 8 Govaert Flinck was born in the German city of Kleve, not far from the Dutch city of Nijmegen, on 25 January 1615. His merchant father, Teunis Govaertsz Flinck, was clearly prosperous, because in 1625 he was appointed steward of Kleve, a position reserved for men of stature.[1] That Flinck would become a painter was not apparent in his early years; in fact, according to Arnold Houbraken, the odds were against his pursuit of that interest. Teunis considered such a career unseemly and apprenticed his son to a cloth merchant. Flinck, however, never stopped drawing, and a fortunate incident changed his fate. According to Houbraken, “Lambert Jacobsz, [a] Mennonite, or Baptist teacher of Leeuwarden in Friesland, came to preach in Kleve and visit his fellow believers in the area.”[2] Lambert Jacobsz (ca. 1598–1636) was also a famous Mennonite painter, and he persuaded Flinck’s father that the artist’s profession was a respectable one. Around 1629, Govaert accompanied Lambert to Leeuwarden to train as a painter.[3] In Lambert’s workshop Flinck met the slightly older Jacob Adriaensz Backer (1608–51), with whom he became lifelong friends. -

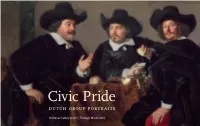

NGA | Civic Pride Group Portraits from Amsterdam

fig. 4 Arent Coster the early stages of the Dutch revolt against (silversmith), Drinking Horn of the Harquebus- Spanish rule (1568 – 1648), the guardsmen iers’ Guild, 1547, buffalo could even be deployed at the front lines, horn mounted on silver pedestal, Rijksmuseum, leading one contemporary observer to Amsterdam, on loan from call them “the muscles and nerves” of the the City of Amsterdam. Dutch Republic. Paintings of governors of civic insti- tutions, such as those by Flinck and Van der Helst, contain fewer figures than do militia group portraits, but they are no less visually compelling or historically signifi- cant. It was only through the efforts of such citizens and organizations that the young Dutch Republic achieved its economic, political, and artistic golden age in the sev- enteenth century. The numerous portraits Harquebusiers’ ceremonial drinking horn room with a platter of fresh oysters is likely of these remarkable people, painted by to the governors. The vessel, a buffalo horn to be Geertruyd Nachtglas, the adminis- important artists, allow us to look back at supported by a rich silver mount in the trator of the Kloveniersdoelen, who had that world and envision the character and form of a stylized tree with a rampant lion assumed that position in 1654 following the appearance of those who were instrumen- and dragon (fig. 4), had been fashioned in death of her father Jacob (seen holding the tal in creating such a dynamic and success- 1547 and was displayed at important events. drinking horn in Flinck’s work). Because ful society. The Harquebusiers’ emblem, a griffin’s the Great Hall was already fully decorated, claw, appears on a gilded shield on the Van der Helst’s painting was installed over This exhibition was organized by the National wall. -

Govert Flinck – Reflecting History’ with an Artistic Intervention by Ori Gersht, Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Cleves / Germany (04/10/2015 – 17/01/2016)

Exhibition ‘Govert Flinck – Reflecting History’ with an artistic intervention by Ori Gersht, Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Cleves / Germany (04/10/2015 – 17/01/2016) The exhibition Govert Flinck – Reflecting History will be shown at the Museum Kurhaus Kleve – Ewald Mataré-Collection from the 4th of October 2015 until the 17th of January 2016. His four hundredth birthday in 2015 provides the occasion for the Museum Kurhaus Kleve to show a comprehensive solo exhibition that will represent the first retrospective in more than fifty years. Govert Flinck (1615-1660), was one of the most prominent portraitists during the Golden Age of Dutch painting and became one of the most celebrated painters of his time in Amsterdam. Even today he is regarded as one of Rembrandt’s most gifted pupils. Already during his lifetime, his fame had by far exceeded that of his teacher. For the Cleves exhibition, precious works on loan from all over the world are expected. 30 paintings and an equal amount of drawings and prints are to illuminate the career of Govert Flinck, his proximity to and dependence on Rembrandt, as well as his development into an artistically independent, successful painter. Both the rich diversity in his oeuvre as well as the high quality of his portraits and historical paintings are made visible. Prints based on his paintings and poetry written about his works give insight into the contemporary reception of his art. Govert Flinck was born on the 25th of January of the year 1615 in Cleves, as son to a well-respected textile trader. In his early youth he moved to Leeuwarden and shortly after to Amsterdam for an education in the art of painting. -

Künstler-Inventare; Urkunden Zur Geschichte Der Holländischen

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/knstlerinventa05bred KUNSTLER-INVENTARE KÜNSTLER-INVENTARE URKUNDEN ZUR GESCHICHTE DER HOLLÄNDISCHEN KUNST DES XVPen^ XVIIten UND XVIIIten JAHRHUNDERTS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON Dr. A. BREDIUS UNTER MITWIRKUNG VON Dr. O. IIIRSCHMANN FÜNFTER TEIL MIT 7 ABBILDUNGEN UND 86 FACSIMILES HAAG MARTINUS NIJIIÜFF 1918 975684 , Inhalt. Seite Vorwort xi Die Nachlass-Versteigerung von Pieter Isaacsz. (Mit Urkunden über Isaac Isaacsz , Matheus van Hoven und Micliiel van de Sande) 1473 Inventar eines Verwandten von Hans van Ebelen (Evelen) 1490 Die Naclilass-Versteigerung von Jan Jansz .... 1494 Das Xachlass-Inventar des Vaters von Simon Root. (Mit Urkunden über Anthony Leemans und Nicolaes ' Lissant) . 1497 Bilderverkauf durch Abraham de Cooge. (Mit Urkunden über Adriaen Hansz Muj-lties) 1511 Das Xachlass-Inventar von Edo Quiter 1523 Inventar von Pieter Ykens 1528 Inventar und Xachlass-Inventar von Jan Blom |Pro- voost], (Mit Urkunden über Jan Pietersz Blom und Jan Huybertsz Blom) 1531 Das Nachlass-lnventar der Witwe von Philips le Petit. (Mit Urkunden über Alexander , Bernardus Philips und Niclaes le Petit und Lucas Verstratei)). 1549 Das Nachlass-lnventar von Willem Willemsz Swin- derwyck 1576 Das Xachlass-Inventar von" Jacob Loys 1588 Das Xachlass-Inventar von Hans van Londerseel . 1594 Inventar von Xicolaes de Bruyn 1599 Vlll — Seite Das Nachlass-Inventar von Maerten Adriaensz Balken- eynde. (]\Iit Urkunden über Floris van Schooten und Jacob Wynants) 1604 Das Nachlass-Inventar von Francois Verwilt. (Mit Urkunden über Adriaen Fransz) 1617 Das Nachlass-Inventar der Witwe von Abraham Verlinde. (Mit Urkunden über Willem Verlinde) . 1629 Das Nachlass-Inventar der Witwe von Crijn Hen- dricksz Volmarijn. -

Catalogue Abrégé Des Tableaux Et Des Sculptures Du Musée Royal De La

r r CATALOGUE ABREGE DES TABLEAUX ET DES SCULPTURES DU MUSEE ROYAL (Mauritshuis) A LA HAYE La Haye 1899 t 3» DES TABLEAUX ET DES SCULPTURES MUSÉE ROYAL DE LA HAYE (Mauritshuis) La Haye i s 99 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 with funding from Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/catalogueabregedOOmaur Le Musée est ouvert gratuitement : du i novembre au i mars, de io à 3 heures. „ 1 mars „ 1 juin, „ 10 „ 4 juin 1 „ 1 ,, septembre, ,, 10 ,, 5 ,, 1 1 ,, septembre ,, novembre, ,, 10 ,, 4 ,, Le dimanche et les jours fériés le Musée n’est ouvert qu’à partir de midi et demi. > INTRODUCTION. Le Mauritshuis, le bâtiment qui renferme le Cabinet Royal de Tableaux, a été construit de 1633 à 1644 par Pieter Post, archi- tecte à la Haye, d’après les plans de Jacob van Campen, depuis architecte de l’Hôtel de ville d’Amsterdam. Il tire son nom de son fondateur, le Comte (plus tard Prince) Jean Maurice de Nas- sau, Gouverneur du Brésil. Lorsque le Prince retourna dans sa patrie, l’édifice était à peu près terminé. Il le décora de nom- breuses oeuvres artistiques, entre autres de paysages peints au Brésil par Frans Post, en mémoire du séjour de ce prince dans l’Amérique méridionale. En 1660 le roi Charles II fut logé dans ce palais pendant le séjour qu’il fit à la Haye, en se rendant en Angleterre. Après la mort du prince Jean Maurice de Nassau, le 20 déc. 1679, le Mauritshuis passa en des mains étrangères et fut loué en 1685 aux Etats députés de la Hollande. -

Catalogue Designer: Laura Scivoli Exhibition Material Visual Design: He Zhao

Index Silent Narratives. Curatorial Concept - Mei Huang .................................................................................... 7 Silent Narratives: A Polyphony Of Stories And Journeys - Dr. Laia Manonelles Moner ................................... 20 Interview on the Exhibition Silent Narratives - Wang Hui ............................................................................. 24 Chinese Hall ............................................................................................................................. 33 Wu Guanzhen .......................................................................................................................... 35 Liu Jianhua ............................................................................................................................... 42 Wang Sishun ............................................................................................................................ 44 Shen Ruijun .............................................................................................................................. 50 Zong Ning ............................................................................................................................... 52 Ding Shiwei .............................................................................................................................. 56 European Hall ......................................................................................................................... 99 Yang Song .............................................................................................................................. -

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague, Netherlands HNA CONFERENCE 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague 2-4 June 2022 Program committee: Stijn Bussels, Leiden University (chair) Edwin Buijsen, Mauritshuis Suzanne Laemers, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History Judith Noorman, University of Amsterdam Gabri van Tussenbroek, University of Amsterdam | City of Amsterdam Abbie Vandivere, Mauritshuis and University of Amsterdam KEYNOTE LECTURES ClauDia Swan, Washington University A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic 1 The global baroque world was a world of goods. Transoceanic trade routes compounded travel over land for commercial gain, and the distribution of wares took on global dimensions. Precious metals, spices, textiles, and, later, slaves were among the myriad commodities transported from west to east and in some cases back again. Taste followed trade—or so the story tends to be told. This lecture addresses the traffic in global goods in the Dutch world from a different perspective—piracy. “A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic” will present and explore exemplary narratives of piracy and their impact and, more broadly, the contingencies of consumption and taste- making as the result of politically charged violence. Inspired by recent scholarship on ships, shipping, maritime pictures, and piracy this lecture offers a new lens onto the culture of piracy as well as the material goods obtained by piracy, and how their capture informed new patterns of consumption in the Dutch Republic. Jan Blanc, University of Geneva Dutch Seventeenth Century or Dutch Golden Age? Words, concepts and ideology Historians of seventeenth-century Dutch art have long been accustomed to studying not only works of art and artists, but also archives and textual sources. -

Courant 7/December 2003

codart Courant 7/December 2003 codartCourant contents Published by Stichting codart P.O. Box 76709 2 A word from the director 12 The influence and uses of Flemish painting nl-1070 ka Amsterdam 3 News and notes from around the world in colonial Peru The Netherlands 3 Australia, Melbourne, National Gallery 14 Preview of upcoming exhibitions [email protected] of Victoria 15 codartpublications: A window on www.codart.nl 3 Around Canada Dutch cultural organizations for Russian 4 France, Paris, Institut Néerlandais, art historians Managing editor: Rachel Esner Fondation Custodia 15 codartactivities in fall 2003 e [email protected] 4 Germany, Dresden, Staatliche Kunst- 15 Study trip to New England, sammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie 29 October-3 November 2003 Editors: Wietske Donkersloot, Alte Meister 23 codartactivities in 2004 Gary Schwartz 5 Germany, Munich, Staatliche 23 codart zevencongress: Dutch t +31 (0)20 305 4515 Graphische Sammlung and Flemish art in Poland, Utrecht, f +31 (0)20 305 4500 6 Italy, Bert W. Meijer’s influential role in 7-9 March 2004 e [email protected] study and research projects on Dutch 23 Study trip to Gdan´sk, Warsaw and and Flemish art in Italy Kraków, 18-25 April 2004 codart board 8 Around Japan 32 Appointments Henk van der Walle, chairman 8 Romania, Sibiu, Brukenthal Museum 32 codartmembership news Wim Jacobs, controller of the Instituut 9 Around the United Kingdom and 33 Membership directory Collectie Nederland, secretary- Ireland 44 codartdates treasurer 10 A typical codartstory Rudi Ekkart, director of the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie Jan Houwert, director of the Wegener Publishing Company Paul Huvenne, director of the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp Jeltje van Nieuwenhoven, member of the Dutch Labor Party faction codartis an international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. -

Portrait of a Girl Wearing a Gold-Trimmed Cloak and Saint Bavo

DATE: October 16, 2009 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EXCEPTIONAL REMBRANDT LOANS COMPLEMENT THE GETTY MUSEUM’S MONUMENTAL REMBRANDT DRAWINGS EXHIBITION Seven Rembrandt paintings on view at the Getty Center include Portrait of a Girl Wearing a Gold-Trimmed Cloak and Saint Bavo LOS ANGELES—In conjunction with the Getty Museum’s major international loan exhibition Drawings by Rembrandt and His Pupils: Telling the Difference, visitors to the Getty Center will also have the opportunity to experience Rembrandt’s artistic genius in the Museum’s East Pavilion paintings galleries through a number of special loans that will be on view in conjunction with this special exhibition. In addition to the Getty’s own Rembrandt paintings, An Old Man in Military Costume, The Abduction of Europa, Daniel and Cyrus Before the Idol Bel, and Saint Bartholomew, which always reside in these galleries as part of the museum’s permanent collection, the Getty will also exhibit several Rembrandt masterpieces on long-term loan, including Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Girl Wearing a Gold-Trimmed Cloak from a private collection and Saint Bavo from the Göteborgs konstmuseum in Sweden. Portrait of a Girl Wearing a Gold-Trimmed Cloak The work, which has not been on public view since the 1970s, is on loan from a private collection in New York. The sitter, an unknown woman, is richly dressed in the fanciful costume Rembrandt favored for biblical and mythological paintings. He scratched in the thick, wet paint to create the pleats of the subject's white shirt, and rendered gold embroidery on her black gown with almost an abstract series of daubs.