Keats Special Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Keats and Fanny Brawne Pages of an Enduring Love

John Keats and Fanny Brawne Pages of an enduring love Source images: http://englishhistory.net/keats/fannybrawne.html “When shall we pass a day alone? I have Read this short account of John Keats’s and Fanny Brawne’s thwarted love story. had a thousand Keats and Fanny, who were newly neighbours, first met in a troubled time for the poet: his mother had died of tuberculosis, soon to be followed by his youngest brother Tom. The teenaged Fanny was not considered beautiful, but she was spirited and kind and Keats was struck by her coquettish sense of fun. Her family’s financialkisses, difficulties influencedfor her with a strong sense of practicality. However, she did fall for young Keats, who was neither well off nor making money through his writing. Her mother against better economical judgement could not prevent a love match, though not without the opposition of Keats’s friends, the two got engaged. Yet, further obstacles were to come. Keats knew his only hope of marrying Fanny was to succeed in writing, since he was often asked by his brother George for moneywhich loans. Inwith February my1820, however, the couple’s future was threatened by illness: Keats had been troubled by what looked like a cold, but later turned out to be a sign of tuberculosis. He was well aware of his worsening condition so at some point he wrote to Fanny that she was free to break their engagement, but she passionately refused to Keats’s relief: “How hurt I should have been hadwhole you ever acceded soul to what I is, notwithstanding, very reasonable!” In an attempt not to upset the poet with too strong emotions, his friend Charles Brown nursed him diligently and kept Fanny at a distance. -

John Keats 1 John Keats

John Keats 1 John Keats John Keats Portrait of John Keats by William Hilton. National Portrait Gallery, London Born 31 October 1795 Moorgate, London, England Died 23 February 1821 (aged 25) Rome, Italy Occupation Poet Alma mater King's College London Literary movement Romanticism John Keats (/ˈkiːts/; 31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of Romantic poets along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death.[1] Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[2] The poetry of Keats is characterised by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analysed in English literature. Biography Early life John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. There is no clear evidence of his exact birthplace.[3] Although Keats and his family seem to have marked his birthday on 29 October, baptism records give the date as the 31st.[4] He was the eldest of four surviving children; his younger siblings were George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez.[5] Another son was lost in infancy. -

January 2017

Registered Charity: 1147589 THE KEATSIAN Newsletter of the Keats Foundation - January 2017 This issue of ‘The Keatsian’ looks forward to forthcoming Keats Foundation events for the spring of 2017. Reported here too is a Keats Foundation lecture at the Plymouth Athenaeum, and a visit to Charles Armitage Brown’s home at Laira, Plymouth, where the first full-length biography of John Keats was written. As this issue of The Keatsian reaches you, we are finalising the development of the new Keats Foundation website – scheduled to go ‘live’ later in the spring of 2017. Dates for your diary: Wednesday, 17 May 2017 at 7 pm: Dr. Margot Waddell and Dr. Toni Griffiths will repeat their acclaimed evening discussing Keats and Negative Capability, at Keats House, Hampstead, in the ‘Nightingale Room’. Tickets will be £5. 00 from Eventbrite; Keats Foundation Supporters, free. Friday 19 May-Sunday 21 May: The fourth Keats Foundation Bicentenary Conference at Keats House, Hampstead: ‘John Keats, 1817: Moments, Meetings, and the Making of a Poet’. See further information in this Newsletter. Thursday 21 September 2017: The Keats Foundation annual Keats House Lecture. Dr. Jane Darcy of UCL will speak on ‘Primrose Island: Keats and the Isle of Wight’. Stop Press! Keats Foundation Photographic Competition announced: go to http://keatsfoundation.com/photography-competition/ Annual Wreath Laying at Westminster Abbey, 31 October 2016 The Keats Foundation organized the laying of our annual wreath for John Keats at Westminster Abbey on 31 October, on the 221st anniversary of the poet's birth. Members of the Keats Foundation and staff and ambassadors of Keats House were joined by Poetry Society and Young Poets Network members. -

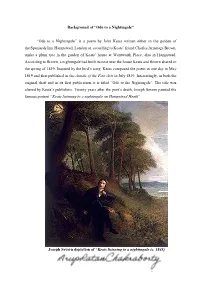

Background of “Ode to a Nightingale” “Ode to a Nightingale” Is a Poem By

Background of “Ode to a Nightingale” “Ode to a Nightingale” is a poem by John Keats written either in the garden of the Spaniards Inn, Hampstead, London or, according to Keats’ friend Charles Armitage Brown, under a plum tree in the garden of Keats’ house at Wentworth Place, also in Hampstead. According to Brown, a nightingale had built its nest near the house Keats and Brown shared in the spring of 1819. Inspired by the bird’s song, Keats composed the poem in one day in May 1819 and first published in the Annals of the Fine Arts in July 1819. Interestingly, in both the original draft and in its first publication, it is titled “Ode to the Nightingale”. The title was altered by Keats’s publishers. Twenty years after the poet’s death, Joseph Severn painted the famous portrait “Keats listening to a nightingale on Hampstead Heath”. Joseph Severn depiction of “Keats listening to a nightingale (c. 1845) Critics generally agree that Nightingale was the second of the five ‘great odes’ of 1819 and its themes are reflected in its ‘twin’ ode, ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’. Of Keats’s major odes of 1819, “Ode to Psyche”, was probably written first and “To Autumn” written last. It is possible that “Ode to a Nightingale” was written between 26 April and 18 May 1819, based on weather conditions and similarities between images in the poem and those in a letter sent to Fanny Keats on May Day. Keats’s friend and roommate, Charles Armitage Brown, described the composition of this beautiful work as follows: “In the spring of 1819 a nightingale had built her nest near my house. -

John Keats - Poems

Classic Poetry Series John Keats - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive John Keats(31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) John Keats was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of romantic poets along with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/george-gordon-lord-byron/">Lord Byron</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/percy-bysshe- shelley/">Percy Bysshe Shelley</a>, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death. Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of later poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life. The poetry of Keats is characterized by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analyzed in English literature. <b>Biography</b> <b>Early Life</b> John Keats was born on 31 October 1795 to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. Keats and his family seemed to have marked his birthday on 29 October, however baptism records give the birth date as the 31st. He was the eldest of four surviving children; George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818) and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889). Another son was lost in infancy. -

BROWN FAMILY Papers, 1841-1983 Reel M 1877

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT BROWN FAMILY Papers, 1841-1983 Reel M 1877 Keats Memorial Library Keats House Keats Grove Hampstead London NM3 2RR National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1984 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES Charles Armitage Brown (1787-1842) was born in London and had little formal education. He started his career as a clerk and as a young man was engaged in the fur-trading business in Russia. In 1817 he met the poet John Keats and together they did a tour of Scotland. For 15 months they shared lodgings at Wentworth Place, a house in Hampstead, and Brown cared for Keats when he developed tuberculosis. He was away in Scotland when Keats left England for Rome, where he died in 1821. In 1822 Brown took his son Carlino to Italy and they lived at Pisa and Florence, sharing a house with the artist Joseph Severn. While living in Italy he met many writers, such as Lord Byron, Walter Savage Landor, Leigh Hunt and Edward Trelawny. In 1835 Brown and Carlino returned to England and settled at Plymouth. In 1840 he became a shareholder in the Plymouth Company, which aimed to colonise New Plymouth in New Zealand. In straitened circumstances, he decided that they should emigrate to New Plymouth. Carlino sailed on the Amelia Thompson and Charles on the Oriental, arriving in October 1841. He died suddenly in the following year. Brown completed a memoir of John Keats in 1836, but it was not published until 1937. Charles (Carlino) Brown (1820-1901) was the son of Charles Armitage Brown and Abigail O’Donohue. -

Keats and Shelley: a Pursuit Towards Progressivism

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-5-2021 Keats And Shelley: A Pursuit Towards Progressivism Serenah Minasian Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Minasian, Serenah, "Keats And Shelley: A Pursuit Towards Progressivism" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 1390. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1390 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KEATS AND SHELLEY: A PURSUIT TOWARDS PROGRESSIVISM SERENAH MINASIAN 58 Pages An analyzation of the poems, letters, and works of John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley from a perspective focusing on the history of sexuality, breaking gender binaries, and pushing towards progressivism. This thesis proves how John Keats is both an effeminate man who displays exemplary ways of breaking gender expectations but also a man who possess misogynistic tendencies. Also, this thesis analyzes Percy Shelley’s use of gender expectations and how he breaks them with the use of his characters. Studying these two British Romantics shows how these two cisgender, straight, white men provide an ability to push back on their time period’s beliefs and impact the writing to come. KEYWORDS: Keats, Shelley, Romanticism, gender, sexuality, feminisms, queer KEATS AND SHELLEY: A PURSUIT TOWARDS PROGRESSIVISM SERENAH MINASIAN A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of English ILLINOIS STATE UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Serenah Minasian KEATS AND SHELLEY: A PURSUIT TOWARDS PROGRESSIVISM SERENAH MINASIAN COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Brian Rejack, Chair Ela Przybylo ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank Dr. -

David Lenson the High Imagination

david lenson The High Imagination Delivered as the Hess Lecture at the University of Virginia, April 29, 1999 he last American combat troops were withdrawn from TSouth Vietnam in August of 1972. The following year, President Richard Nixon’s campaign promise of a “War on Drugs” was kept at last, when several small federal agencies were consolidated to form the Drug Enforcement Administration. The timing was not a coincidence. Someone had to be held responsible for America’s first defeat in war. It would have been unseemly to condemn the soldiers themselves, after the enormous losses they had sustained, and it would not have been credible to blame the domestic antiwar movement or the counterculture. But scapegoating “drugs” was a way to get them all at the same time. The War on Drugs, since its redeclaration by President Ronald Reagan, continues to be part of a broader campaign to discredit “the 60s,” that last significant resistance to consumerism. But the counter- culture, which seemed so radically new at the time, was at heart a mass Romantic revival, a reincarnation not only of domestic transcenden- talism, but also of European doctrines of imagination and expressive art. Drug warriors and conservative cultural critics seem to remember better than literary scholars that our operative idea of imagination, dating back to the tail end of the eighteenth century, is inextricably linked to our history of intoxication. You might suppose that “War on Imagination” would have made a truer declaration. Four years ago , Harvard Magazine reported that “In 1987 the Austrian-born Dr. Werner Baumgartner analyzed a lock of hair from the head of English poet John Keats . -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. William Wordsworth, The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, ed. E. De Selincourt, second revised edition, ed. Mary Moorman and Alan G. Hill, 7 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967–88), VII, p. 838. 2. Recollections of the Table-Talk of Samuel Rogers, ed. Bishop Morchard (London: Richards, 1952), p. 282. 3. During Cary’s lifetime there were four editions of The Vision: 1814, 1819, 1831 and 1844. Cary’s biographer, W.J. King, counted as many as twenty editions of The Vision between the poet’s death and the 1920s. The Translator of Dante (London: Secker, 1925), p. 285. 4. Gilbert F. Cunningham, The Divine Comedy in English: a Critical Bibliography 1782–1900, 2 vols (Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd, 1965–66), pp. 6–8. 5. Henry Cary, Memoir, II, pp. 18–19. The meeting took place in the autumn of 1817. 6. See especially Jerome McGann, ‘Rethinking Romanticism: the Challenge of Periodisation’, English Literary History, 59 (1992), pp. 735–54. 7. See for instance, Marshall Brown’s introduction to the Cambridge History of Literary Criticism: Romanticism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989). 8. For Lamb’s iconoclasm, see Luisa Calè, ‘“The Vantage-Ground of Abstraction”: Charles Lamb on Reading and Viewing’, in Image and Word; Reflections of Art and Literature from the Middle Ages to the Present, ed. A. Braida and Giuliana Pieri (Oxford: Legenda, 2003), pp. 135–50. For Blake’s attitude towards ‘Republican Arts’, see John Barrell and Morris Eaves, The Counter-Arts Conspiracy: Art and Industry in the Age of Blake (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1992); John Barrell, The Political Theory of Painting from Reynolds to Hazlitt: ‘The Body of the Public’ (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986). -

Guide to the Edward John Trelawny Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt287032sm No online items Guide to the Edward John Trelawny Collection Finding aid created by Sarah Jaques-Ross, 2009 Special Collections, Honnold/Mudd Library, Claremont University Consortium2009 Libraries of The Claremont Colleges 800 N. Dartmouth Avenue Claremont, CA 91711 Phone: (909) 607-3977 Fax: (909) 621-8681 Email: [email protected] URL: http://libraries.claremont.edu/sc/default.html © 2009 Claremont University Consortium. All rights reserved. Guide to the Edward John h2007.7 1 Trelawny Collection Descriptive Summary Title: Guide to the Edward John Trelawny Collection creator: Prell, Donald B. Dates: 1821-2008 Extent: 3 feet (2 boxes) (1 oversized box) Repository: Claremont Colleges. Honnold/Mudd Library. 800 N. Dartmouth Avenue Special Collections, Honnold/Mudd Library Claremont University Consortium Claremont, California 91711 Abstract: This collection was compiled by Donald Prell as a result of his research on Edward John Trelawny. The collection, therefore, contains primary and secondary source information about Edward John Trelawny and his relationships with Percy B. Shelley, Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont, Edward Ellerker Williams, and others of his time. The materials include copies of letters, diaries, images, and articles ranging from 1821 to 2008. Collection Number: h2007.7 Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Physical Location: Special Collections, Honnold/Mudd Library. Claremont University Consortium. Restrictions on Access This collection is open for research. Publication Rights For permissions to reproduce or to publish, please contact Special Collections Library staff. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Edward John Trelawny Collection. Special Collections, Honnold Mudd Library, Claremont University Consortium. Acquisition Information Gift of Donald B. -

1 Keats, Leigh Hunt and Shelley Detailed Listing

KEATS, LEIGH HUNT AND SHELLEY DETAILED LISTING REEL 1 KEATS MATERIAL 1. Add 37000 – Hyperion, poem Add Ms 37000. " HYPERION," a poem by JOHN KEATS written between Sept. 1817 and April, 1818, and first printed in the volume entitled, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and other Poems, 1820. Holograph, with numerous cancellings, emendations and additions, all in the poet's own hand. The MS. was probably given by Keats to Leigh Hunt, whose son Thornton Hunt about 1862 gave it to Miss Alice Bird, from whom it was acquired for the Museum, 8 Oct. 1904. lt was previously unknown to any of the editors and biographers of Keats, the only MS. authority available being a fair copy made for the press by the poet's friend Richard Woodhouse. A collotype facsimile, ed. E de Sélincourt, was published by the Oxford Univ. Press in 1905. Paper; ff. 27. 15 3/4 in. x 9 1/2 in. 2. Eg 2780 ‐ Pot of Basil, St Agnes & other poems Eg. 2,780. POEMS by John Keats, partly autograph. The contents are as follows (a) " The Pot, of' Basil." Autogragh. f. 1 ;‐ (b) "Ode" [on the Mermaid tavern ] Autogr. f. 29;‐ (c) "Song," beg. "Hence Burgundy, Claret, and Port." f. 30;‐ (d) "Saint Agnes Eve." ff. 31, 37;‐ (e) "The Eve of St. Mark." Autogr. f. 33 ;‐ (f) " Ode oil Melancholy." f. 52;‐ (g) " Ode to the Nightingale." f. 53;‐ (h) " Ode on a Grecian Urn." f. 55 ; ‐ (i) "Fragment," beg. " Welcome joy, and welcome sorrow." f. 56;‐ (k) " Fragment," beg. " Where's the Poet ?" f. -

John Keats 1795-1821

http://www.englishworld2011.info/ 878 JOHN KEATS 1795-1821 John Keats's father was head stableman at a London livery stable; he married his employer's daughter and inherited the business. The poet's mother, by all reports, was an affectionate but negligent parent to her children; remarrying almost imme- diately after a fall from a horse killed her first husband, she left the eight-year-old John (her firstborn), his brothers, and a sister with their grandmother and did not reenter their lives for four years. The year before his father's death, Keats had been sent to the Reverend John Clarke's private school at Enfield, famous for its progressive curriculum, where he was a noisy, high-spirited boy; despite his small stature (when full-grown, he was barely over five feet in height), he distinguished himself in sports and fistfights. Here he had the good fortune to have as a mentor Charles Cowden Clarke, son of the headmaster, who later became a writer and an editor; he encour- aged Keats's passion for reading and, both at school and in the course of their later friendship, introduced him to Spenser and other poets, to music, and to the theater. When Keats's mother returned to her children, she was already ill, and in 1810 she died of tuberculosis. Although the livery stable had prospered, and £8,000 had been left in trust to the children by Keats's grandmother, the estate remained tied up in the law courts for all of Keats's lifetime. The children's guardian, Richard Abbey, an unimaginative and practical-minded businessman, took Keats out of school at the age of fifteen and bound him apprentice to Thomas Hammond, a surgeon and apothecary at Edmonton.