1989 No Revolution Without Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering East German Childhood in Post-Wende Life Narratives" (2013)

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2013 Remembering East German Childhood In Post- Wende Life Narratives Juliana Mamou Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mamou, Juliana, "Remembering East German Childhood In Post-Wende Life Narratives" (2013). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 735. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. REMEMBERING EAST GERMAN CHILDHOOD IN POST-WENDE LIFE NARRATIVES by JULIANA MAMOU DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2013 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: _____________________________________ Advisor Date _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY JULIANA MAMOU 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to the members of my Dissertation Committee, Professor Donald Haase, Professor Lisabeth Hock, and Professor Anca Vlasopolos, for their constructive input, their patience, and support. I am particularly grateful for the assistance -

Motion: Europe Is Worth It – for a Green Recovery Rooted in Solidarity and A

German Bundestag Printed paper 19/20564 19th electoral term 30 June 2020 version Preliminary Motion tabled by the Members of the Bundestag Agnieszka Brugger, Anja Hajduk, Dr Franziska Brantner, Sven-Christian Kindler, Dr Frithjof Schmidt, Margarete Bause, Kai Gehring, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Dr Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth, Manuel Sarrazin, Jürgen Trittin, Ottmar von Holtz, Luise Amtsberg, Lisa Badum, Danyal Bayaz, Ekin Deligöz, Katja Dörner, Katharina Dröge, Britta Haßelmann, Steffi Lemke, Claudia Müller, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Erhard Grundl, Dr Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Christian Kühn, Stephan Kühn, Stefan Schmidt, Dr Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Markus Tressel, Lisa Paus, Tabea Rößner, Corinna Rüffer, Margit Stumpp, Dr Konstantin von Notz, Dr Julia Verlinden, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Gerhard Zickenheiner and the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group be to Europe is worth it – for a green recovery rooted in solidarity and a strong 2021- 2027 EU budget the by replaced The Bundestag is requested to adopt the following resolution: I. The German Bundestag notes: A strong European Union (EU) built on solidarity which protects its citizens and our livelihoods is the best investment we can make in our future. Our aim is an EU that also and especially proves its worth during these difficult times of the corona pandemic, that fosters democracy, prosperity, equality and health and that resolutely tackles the challenge of the century that is climate protection. We need an EU that bolsters international cooperation on the world stage and does not abandon the weakest on this earth. proofread This requires an EU capable of taking effective action both internally and externally, it requires greater solidarity on our continent and beyond - because no country can effectively combat the climate crisis on its own, no country can stamp out the pandemic on its own. -

The GDR Opposition Archive

The GDR Opposition Archive in the Robert Havemann Society The GDR Opposition Archive in the Robert Havemann Society holds the largest accessible collection of testaments to the protest against the SED dictatorship. Some 750 linear metres of written material, 180,000 photos, 5,000 videos, 1,000 audio cassettes, original banners and objects from the years 1945 to 1990 all provide impressive evidence that there was always contradiction and resistance in East Germany. The collection forms a counterpoint and an important addition to the version of history presented by the former regime, particularly the Stasi files. Originally emerging from the GDR’s civil rights movement, the archive is now known beyond Germany itself. Enquiries come from all over Europe, the US, Canada, Australia and Korea. Hundreds of research papers, radio and TV programmes, films and exhibitions on the GDR have drawn on sources from the collection. Thus, the GDR Opposition Archive has made a key contribution to our understanding of the communist dictatorship. Testimonials on opposition and resistance against the communist dictatorship The GDR Opposition Archive is run by the Robert Havemann Society. It was founded 26 years ago, on 19 November 1990, by members and supporters of the New Forum group, including prominent GDR opposition figures such as Bärbel Bohley, Jens Reich, Sebastian Pflugbeil and Katja Havemann. To this day, the organisation aims to document the history of opposition and resistance in the GDR and to ensure it is not forgotten. The Robert Havemann Society has been funded entirely on a project basis since its foundation. Its most important funding institutions include the Berlin Commissioner for the Stasi Records and the Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship. -

A Global Assistance Package to Tackle the Global Coronavirus Pandemic 7

A global assistance package to tackle the global coronavirus pandemic 7 April 2020 The coronavirus is a global challenge, and a global response is therefore the only option. No country can cope with the coronavirus crisis and its already devastating consequences alone. If we work against each other, we will all lose in the end. We can and will only overcome this crisis through cooperation and dialogue. In many countries, including in Germany, public, economic and cultural life has been at a standstill for weeks. Drastic steps have been taken to keep health systems from collapsing. And nonetheless, we are anxiously looking at the infection graphs and worrying about our family members and friends. Like many other countries, Germany has put together an unprecedented rescue package for businesses and workers to contain the economic and social consequences. Unfortunately, not all countries are in a position to do so. The coronavirus is impacting everyone, irrespective of their origins, gender or skin colour. Yet, already vulnerable populations are most affected. This applies, in particular, to people who live in countries with weakened public institutions and health systems, where social safety nets are inadequate or non-existent, and where there is a lack of access to clean water and sanitation facilities. In addition, the economic consequences and responses are distributed unevenly: while many European countries, the United States and China can afford to put together gigantic assistance packages at short notice, many developing countries are much more likely to plunge into devastating economic and currency crises. We therefore need a global response to the coronavirus crisis which is based on solidarity. -

The Divided Nation a History of Germany 19181990

Page iii The Divided Nation A History of Germany 19181990 Mary Fulbrook Page 318 Thirteen The East German Revolution and the End of the Post-War Era In 1989, Eastern Europe was shaken by a series of revolutions, starting in Poland and Hungary, spreading to the GDR and then Czechoslovakia, ultimately even toppling the Romanian communist regime, and heralding the end of the post-war settlement of European and world affairs. Central to the ending of the post-war era were events in Germany. The East German revolution of 1989 inaugurated a process which only a few months earlier would have seemed quite unimaginable: the dismantling of the Iron Curtain between the two Germanies, the destruction of the Berlin Wall, the unification of the two Germanies. How did such dramatic changes come about, and what explains the unique pattern of developments? To start with, it is worth reconsidering certain features of East Germany's history up until the 1980s. The uprising of 1953 was the only previous moment of serious political unrest in the GDR. It was, as we have seen above, limited in its origins and initial aims-arising out of a protest by workers against a rise in work norms-and only developed into a wider phenomenon, with political demands for the toppling of Ulbricht and reunification with West Germany, as the protests gained momentum. Lacking in leadership, lacking in support from the West, and ultimately repressed by a display of Soviet force, the 1953 uprising was a short-lived phenomenon. From the suppression of the 1953 revolt until the mid-1980s, the GDR was a relatively stable communist state, which gained the reputation of being Moscow's loyal ally, communism effected with Prussian efficiency. -

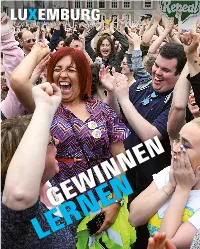

Lu X Embu Rg

01 01 21 21 GESELLSCHAFTSANALYSE UND LINKE PRAXIS Lia Becker | Eric Blanc | Marcel Bois | Ulrike Eifler | Naika Foroutan | Alexander Harder | Paul Heinzel | Susanne Hennig-Wellsow | EMBURG Olaf Klenke | Elsa Koester | Kalle Kunkel | X Susanne Lang | Max Lill | Thomas Lißner | LU Rika Müller-Vahl | Sarah Nagel | Benjamin Opratko | Luigi Pantisano | Hanna Pleßow | Katrin Reimer-Gordinskaya | Thomas Sablowski | Daniel Schur | Jana Seppelt | Jeannine Sturm | Selana Tzschiesche | Jan van Aken | Moritz Warnke | Florian Weis | Janine Wissler | Lou Zucker Grün-schwarze Lovestory Corona und die Kultur der Ablehnung Aufbruch Ost Enteignen lernen Wahlkampf mit Methode Zetkin entdecken Antisemitismus im Alltag GEWINNEN LERNEN DIE ZEITSCHRIFT DER ROSA-LUXEMBURG-STIFTUNG ISSN 1869-0424 GEWINNEN LERNEN » Man muss ins Gelingen verliebt sein, nicht ins Scheitern. Ernst Bloch GEWINNEN LERNEN Wenn du anfängst, hast du einen Hammer. Und wenn du einen Hammer hast, sieht alles aus wie ein Nagel. Aber wenn man mehr Methoden kennenlernt, dann hat man plötzlich einen Schrauben - schlüssel, man hat eine Zange und man kann seinen Werkzeugen immer neue hinzufügen. »Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez EDITORIAL Manchmal verdichten sich gesellschaftliche Krisen- PRONOMEN BUSFAHRERIN mo mente in einem einzigen Wort. So war »Corona- Fridays for Future goes Arbeitskampf pan de mie« Wort des Jahres 2020, davor war es »Re spektrente«, und 2018 »Heißzeit«. Es sind die Gespräch mit Rika Müller-Vahl und Heraus forderungen unserer Gegenwart: das Ringen Paul Heinzel um eine solidarische Pandemiepolitik und gute Da- seinsvorsorge für alle, das Rennen gegen die Klima- katastrophe und der Kampf um einen Strukturwan- ALLIANZ DER del, der niemanden zurücklässt. Und das Wort des AUSGEGRENZTEN? Jahres 2021? Derzeit scheinen »Kanzlerkandidatin«, Was Ostdeutsche und »Schwarz-Grün« oder »Weiter-so« hoch im Kurs. -

Interview with J.D. Bindenagel

Library of Congress Interview with J.D. Bindenagel The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR J.D. BINDENAGEL Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 3, 1998 Copyright 2002 ADST Q: Today is February 3, 1998. The interview is with J.D. Bindenagel. This is being done on behalf of The Association for Diplomatic Studies. I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. J.D. and I are old friends. We are going to include your biographic sketch that you included at the beginning, which is really quite full and it will be very useful. I have a couple of questions to begin. While you were in high school, what was your interest in foreign affairs per se? I know you were talking politics with Mr. Frank Humphrey, Senator Hubert Humphrey's brother, at the Humphrey Drugstore in Huron, South Dakota, and all that, but how about foreign affairs? BINDENAGEL: I grew up in Huron, South Dakota and foreign affairs in South Dakota really focused on our home town politician Senator and Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. Frank, Hubert Humphrey's brother, was our connection to Washington, DC, and the center of American politics. We followed Hubert's every move as Senator and Vice President; he of course was very active in foreign policy, and the issues that concerned South Dakota's farmers were important to us. Most of farmers' interests were in their wheat sales, and when we discussed what was happening with wheat you always had to talk about the Russians, who were buying South Dakota wheat. -

REFORM, RESISTANCE and REVOLUTION in the OTHER GERMANY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository RETHINKING THE GDR OPPOSITION: REFORM, RESISTANCE AND REVOLUTION IN THE OTHER GERMANY by ALEXANDER D. BROWN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music University of Birmingham January 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The following thesis looks at the subject of communist-oriented opposition in the GDR. More specifically, it considers how this phenomenon has been reconstructed in the state-mandated memory landscape of the Federal Republic of Germany since unification in 1990. It does so by presenting three case studies of particular representative value. The first looks at the former member of the Politbüro Paul Merker and how his entanglement in questions surrounding antifascism and antisemitism in the 1950s has become a significant trope in narratives of national (de-)legitimisation since 1990. The second delves into the phenomenon of the dissident through the aperture of prominent singer-songwriter, Wolf Biermann, who was famously exiled in 1976. -

Annual Report the Heinrich Böll House in Langenbroich

The Heinrich Böll Foundation Table of Contents Mission Statement The Heinrich Böll Foundation, affiliated with the Green project partners abroad is on a long-term basis. Additional Party and headquartered in the heart of Berlin, is a legally important instruments of international cooperation include independent political foundation working in the spirit of intel- visitor programs, which enhance the exchange of experiences Who We Are, What We Do lectual openness. The Foundation’s primary objective and political networking, as well as basic and advanced train- The Heinrich Böll Foundation is part of the Green political To achieve our goals, we seek strategic partnerships with is to support political education both within Germany and ing programs for committed activists. The Heinrich Böll movement that has developed worldwide as a response to the others who share our values. We are an independent organi- abroad, thus promoting democratic involvement, sociopo- Foundation’s Scholarship Program considers itself a workshop traditional politics of socialism, liberalism, and conservatism. zation, that is, we determine our own priorities and policies. litical activism, and cross-cultural understanding. The for the future; its activities include providing support to espe- Our main tenets are ecology and sustainability, democracy and We are based in the Federal Republic of Germany, yet we Foundation also provides support for art and culture, science cially talented students and academicians, promoting theoret- human rights, self-determination and justice. We place parti- are an international actor in both ideal and practical terms. and research, and development cooperation. Its activities are ical work of sociopolitical relevance, and working to overcome cular emphasis on gender democracy, meaning social emanci- Our namesake, the writer and Nobel Prize laureate guided by the fundamental political values of ecology, demo- the compartmentalization of science into exclusive subjects. -

The Rhetorical Crisis of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

THE RHETORICAL CRISIS OF THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL: FORGOTTEN NARRATIVES AND POLITICAL DIRECTIONS A Dissertation by MARCO EHRL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Nathan Crick Committee Members, Alan Kluver William T. Coombs Gabriela Thornton Head of Department, J. Kevin Barge August 2018 Major Subject: Communication Copyright 2018 Marco Ehrl ABSTRACT The accidental opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9th, 1989, dismantled the political narratives of the East and the West and opened up a rhetorical arena for political narrators like the East German citizen movements, the West German press, and the West German leadership to define and exploit the political crisis and put forward favorable resolutions. With this dissertation, I trace the neglected and forgotten political directions as they reside in the narratives of the East German citizen movements, the West German press, and the West German political leadership between November 1989 and February 1990. The events surrounding November 9th, 1989, present a unique opportunity for this endeavor in that the common flows of political communication between organized East German publics, the West German press, and West German political leaders changed for a moment and with it the distribution of political legitimacy. To account for these new flows of political communication and the battle between different political crisis narrators over the rhetorical rights to reestablish political legitimacy, I develop a rhetorical model for political crisis narrative. This theoretical model integrates insights from political crisis communication theories, strategic narratives, and rhetoric. -

Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle William D

History Faculty Publications History 11-7-2014 Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle William D. Bowman Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac Part of the Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Eastern European Studies Commons, European History Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Bowman, William D. "Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle." Philly.com (November 7, 2014). This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/53 This open access opinion is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle Abstract When the Berlin Wall fell 25 years ago, on Nov. 9, 1989, symbolically signaling the end of the Cold War, it was no surprise that many credited President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for bringing it down. But the true heroes behind the fall of the Berlin Wall are those Eastern Europeans whose protests and political pressure started chipping away at the wall years before. East -

Dezember 2017

★ ★ ★ Dezember ★ ★ 2017 ★ ★ ★ Vereinigung ehemaliger Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestages und des Europäischen Parlaments e. V. Editorial Rita Pawelski Informationen ...Grüße aus dem Saarland Termine Personalien Titelthemen Mitgliederreise Saarland und Luxemburg Berichte / Erlebtes Europäische Assoziation Jahreshauptversammlung in Bonn Mein Leben danach Erlesenes Aktuelles Die Geschäftsführerin informiert Jubilare © Carmen Pägelow Editorial Informationen Willkommen in der Vereinigung der ehemaligen Abgeordneten, Termine © Thomas Rafalzyk liebe neue Ehemalige! 20.03.2018 Frühlingsempfang der DPG (voraussichtlich) Für mehr als 200 Abgeordnete 21.03.2018 Mitgliederversammlung der DPG (voraussichtlich) beginnt nun eine neue Lebens- 14./15.05.2018 Mitgliederveranstaltung mit zeit. Sie gehören dem Deutschen Empfang des Bundespräsidenten / Bundestag nicht mehr an. Je Jahreshauptversammlung mit Wahl / nach Alter starten sie entweder Studientag „Die Zukunft Europas“ in eine neue Phase der Berufs- 12.-20. Juni 2018 Mitgliederreise nach Rumänien tätigkeit oder sie bereiten sich auf ihren dritten Lebensabschnitt vor. Aber egal, was für sie für sich und ihre Zukunft geplant haben: die Zeit im Bundestag ist nun Vergangenheit. Personalien Ich weiß aus Erfahrung, dass der Übergang in die neue Zeit von vielen Erinnerungen – und manchmal auch von Wehmut – begleitet wird. Man hat doch aus Überzeugung im Deutschen Bundestag gearbeitet… und oft auch mit Herzblut. Man hatte sich an den Arbeitsrhythmus gewöhnt und daran, dass der Tag oft 14 bis 16 Arbeitsstunden hatte. Man schätzte die fleißigen Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter im Büro, die Planungen über- © Deutscher Bundestag / Achim Melde nommen, Reisen gebucht, an Geburtstage erinnert, den Termin- kalender geführt, Sitzungen vorbereitet und Akten sortiert haben. Auf einmal ist man selbst dafür zuständig: welchen Zug muss ich nehmen, wann fährt der Bus, wer hat wann Geburtstag.