Pacific Basin Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

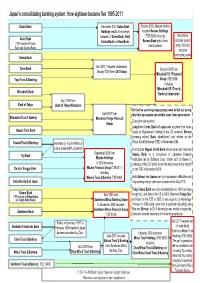

Japanâ••S Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

Japan’s consolidating banking system: How eighteen became five 1995-2013 Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki Red border (TSE 8308) including Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current (1991 merger of Kyowa Osaka Bank and Nara Bank. trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (TSE 8306) Toyo Trust & Banking including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega-groups were bailed out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank, rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due to long-running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group (TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trust & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010. -

Japanese Banks' Monitoring Activities

Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996* Paper Prepared for the CGP Conference Macro/Financial Issues and International Economic Relations: Policy Options for Japan and the United States October 22-23, 2004, Ann Arbor Kyoji Fukao** Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University and RIETI Kiyohiko G. Nishimura Faculty of Economics, University of Tokyo and ESRI, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan Qing-Yuan Sui Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Yokohama City University, Masayo Tomiyama Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University * We are grateful to the participants of the pre-conference meeting of the CGP project and a seminar held at Hitotsubashi University for their comments and suggestions on a preliminary version of this paper. ** Correspondence: Kyoji Fukao, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Naka 2-1, Kunitachi, Tokyo 186-8603 JAPAN. Tel.: +81-42-580-8359, Fax.: +81-42-580-8333, e-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Using micro data of Japanese banks and borrower firms, we construct an index measure that quantitatively describes the monitoring activities of Japanese banks. We examine the effects of bank monitoring on the profitability of borrower firms. We find significant positive effects in the periods 1986-1991 and 1992-1996, although there is no significant effect in the 1981-1985 period . We also examine how banks' monitoring affects borrowers. The results show that the positive effects of banks' monitoring on borrowers' profitability are mostly caused by screening effects, not performance-improving effects. 1 Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996 One of the most dramatic developments in the Japanese economy during the 1990s concerns the fate of the country's banks. -

Does the Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk?: Evidence From

WorkingPaper Series Does The Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk? Evidence from Financial Firm Failures Elijah Brewer III, Hesna Genay, William Curt Hunter and George G. Kaufman Working Papers Series Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago December 1999 (WP-99-31) ,11111 Wifi iiilli™iIIII§«lf III! • FEDERAL RESERVE BANK !!fl!!l!l||ll!illll OF CHICAGO i s Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis DOES THE JAPANESE STOCK MARKET PRICE BANK RISK? EVIDENCE FROM FINANCIAL FIRM FAILURES Elijah Brewer HI* Hesna Genay* William Curt Hunter* George G. Kaufman** December 1999 * Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago ** Loyola University Chicago and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Corresponding author: Hesna Genay, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Economic Research, 230 S. LaSalle Street, Chicago, IL 60604. [email protected]. The research assistance of Scott Briggs, Kenneth Housinger, George Simler, and Alex Urbina is greatly appreciated. The authors also would like to thank Anil Kashyap, participants at the The Sixth Annual Global Finance Conference, The Thirty-Fifth Annual Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, and 1999 FMA Meetings for valuable comments, and Rieko McCarthy of Moody’s Investor Services for the information she so kindly provided. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Federal Reserve System. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ABSTRACT The efficiency of Japanese stock market to appropriately price the riskiness of Japanese firms has been frequently questioned, particularly with respect to Japanese banks which have experienced severe financial distress in recent years. -

Japan's Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

-DSDQVFRQVROLGDWLQJEDQNLQJV\VWHP+RZHLJKWHHQEHFDPHILYH Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki (TSE 8308) including Red border Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current Osaka Bank and Nara Bank . (1991 merger of Kyowa trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Toyo Trust & Banking Group (TSE 8306) including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega -groups were ba iled out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank , rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. to long -running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai -ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group ( TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trus t & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010. -

Karafuto 1945: an Examination of the Japanese Under Soviet Rule and Their Subsequent Expulsion

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-21-2015 Karafuto 1945: An examination of the Japanese under Soviet rule and their subsequent expulsion Cameron Carson Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Carson, Cameron, "Karafuto 1945: An examination of the Japanese under Soviet rule and their subsequent expulsion" (2015). Honors Theses. 2557. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2557 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Karafuto 1945: An Examination of the Japanese Under Soviet Rule and Their Subsequent Expulsion By Cameron B. Carson 1 Introduction The year 1945 saw the end of the Second World War, which claimed millions of lives from both civilians and members of the military. 1945 was also the beginning of another type of conflict, namely the Cold War, which the USA and USSR fought through proxy and filled both with fear. One of the issues that many historians overlook between the two superpowers is the repatriation of Japanese nationals who were left in a remote part of the former Japanese Empire that fell under the control of the USSR in the closing days of the war. This paper will look at the stories of the Japanese nationals left behind on Sakhalin Island (or “Karafuto” as it was known to the Japanese) after it was invaded and subsequently occupied by the USSR in August 1945. -

A Brave New World for M&A of Financial Institutions in Japan: Big

A BRAVE NEW WORLD FOR M&A OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN JAPAN: BIG BANG FINANCIAL DEREGULATION AND THE NEW ENVIRONMENT FOR CORPORATE COMBINATIONS OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS ERic C. SIBBITT" 1. INTRODUCTION Japanese financial institutions have long been shackled by a web of legal restriction and labyrinthine regulation that has segmented financial institutions into limited fiefdoms, insularly limiting their ability to compete against one another. The catastrophic result of such daimyo-style regulation1 is evident in the general non-competitiveness of Japanese financial institutions, massive nonperforming loan problems, and the bankruptcies of several prominent financial institutions. In response to this financial malaise, Japan recently has begun loosening many of the legal shackles that have, inter alia, traditionally prohibited and restricted mergers and acquisitions of financial institutions in Japan's tightly segmented financial industry. The poor performance of Japanese financial institutions has given them the incentive to utilize this freedom to combine in new ways to achieve business objectives in an environment less encumbered by restrictions on financial integration. As financial institutions, both domestic and foreign, * Associate, White & Case LLP, Tokyo; LL.M. Kyushu University; J.D. Harvard University; A.B. University of California at Berkeley. The author would like to thank in particular Professor Toshimitsu Kitagawa for introducing me to officials at the Japanese Fair Trade Commission, Professor Luke Nottage for his comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and the Japanese Ministry of Education Scholarship Program (Monbusho) for providing financial assistance, making this research possible. 1 Daimyo were Japanese feudal fiefdoms headed by feudal lords, through which the Japanese Shogun indirectly controlled Japan. -

Consolidation of Banks in Japan: Causes and Consequences

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CONSOLIDATION OF BANKS IN JAPAN: CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES Kaoru Hosono Koji Sakai Kotaro Tsuru Working Paper 13399 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13399 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2007 We appreciate valuable comments from Andy Rose, Taka Ito, Hiro Ito, Barry Williams, and other participants at NBER EASE 18th Conference. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Kaoru Hosono, Koji Sakai, and Kotaro Tsuru. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Consolidation of Banks in Japan: Causes and Consequences Kaoru Hosono, Koji Sakai, and Kotaro Tsuru NBER Working Paper No. 13399 September 2007 JEL No. G21,G34 ABSTRACT We investigate the motives and consequences of the consolidation of banks in Japan during the period of fiscal year 1990-2004 using a comprehensive dataset. Our analysis suggests that the government's too-big-to-fail policy played an important role in the mergers and acquisitions (M&As), though its attempt does not seem to have been successful. The efficiency-improving motive also seems to have driven the M&As conducted by major banks and regional banks in the post-crisis period, while the market-power motive seems to have driven the M&As conducted by regional banks and corporative (shinkin) banks. We obtain no evidence that supports managerial motives for empire building. -

Japan's Decade-Long Recession

Kobe University Repository : Kernel タイトル JAPAN'S DECADE-LONG RECESSION Title 著者 Uematsu, Tadahiro Author(s) 掲載誌・巻号・ページ Kobe University Economic Review,45:19-29 Citation 刊行日 1999 Issue date 資源タイプ Departmental Bulletin Paper / 紀要論文 Resource Type 版区分 publisher Resource Version 権利 Rights DOI JaLCDOI 10.24546/81000919 URL http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/handle_kernel/81000919 PDF issue: 2021-10-07 Kobe University Economic Review 45 (J 999) 19 JAPAN'S DECADE-LONG RECESSION By TADAHIRO UEMATSU This paper attempts to analyze the structure of the decade-long Heisei Recession by clarifying the relation of the causes and effects of the recession from the start of the bub ble in the 1980s to the end of the recession in 1999. It is revealed that the reason why the Heisei Recession was so long and so severe lies in the fact that, because two causes of the recession (the continuous fall of land prices and the insolvency of financial institu tions) were new for the Japanese, the government made errors in finding policies appropri ate to overcome the recession. It was after passing the "nightmare" in the autumn of 1997 that the government established a system of financial stability which enabled the Japanese economy to get out of this recession. However, there are several tasks with which the Japanese economy has to cope in the near future. 1. Introduction Ten years have passed since the Japanese economy fell into the current Heisei Reces sion. It has been the longest recession since W orId War II. Rapid economic growth at an average of 10% per year was enjoyed in the 1950s and 60s, and moderate growth at an average of 5 % per year was achieved in the 1970s and 80s. -

Hollowing-Out of Japanese Industries and Creation of Knowledge-Intensive Clusters

Hollowing-out of Japanese Industries and Creation of Knowledge-Intensive Clusters Introduction 1. Hollowing-out of the Electric Machinery and Appliance Manufacturing Industry 2. Restructuring of Banking Industry and the Boards of Directors 3. Trends in Economic Policies Designed to Encourage New Industries in Japan Haruo Horaguchi Professor, Faculty of Business Administration, Hosei University. Director, the Research Institute for Innovation Management, Hosei University March 26, 2004 Paper presented for the international symposium, “Globalization and Revitalization of Industrial and Regional Employment: Comparison of Germany and Japan,” organized by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, in collaboration with the Research Institute of Innovation Management, Hosei University. 1 Introduction This paper offers a general view on changes in Japan’s employment structures and summarizes trends in the economic policy measures taken within Japan to encourage new industries. The institutional conditions will also be discussed in order to ensure the vitality and effectiveness of the creation of new industries. Section 1 deals with the electric machinery and appliance manufacturing industry as an example of industrial hollowing-out. This section reveals the quantitative changes in employment which occurred amongst Japanese multinational firms during the 1990s, by comparing data from Census of Manufactures (Kougyo Toukei Hyo) and data from annual financial reports. Section 2 traces the manner in which boards of director members changed within the Japanese banking industry during the restructuring process of the 1990s. Section 3 searches for those conditions that enable political measures to function favorably while at the same time reviewing government measures that encourage the creation of new businesses and their effects on employment. -

Too Big to Fail" Prevail?

Title Banking in Japan: Will "Too Big To Fail" Prevail? Rixtel, Adrian van; Wiwattanakantang, Yupana; Author(s) Souma, Toshiyuki; Suzuki, Kazunori Citation Issue Date 2002-12 Type Technical Report Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/10086/13912 Right Hitotsubashi University Repository Center for Economic Institutions Working Paper Series CEI Working Paper Series, No. 2002-16 Banking in Japan: Will “To Big to Fail” Prevail? Adrian van Rixtel Yupana Wiwattanakantang Toshiyuki Souma Kazunori Suzuki Center for Economic Institutions Working Paper Series Institute of Economic Research Hitotsubashi University 2-1 Naka, Kunitachi, Tokyo, 186-8603 JAPAN Tel: +81-42-580-8405 Fax: +81-42-580-8333 e-mail: [email protected] Banking in Japan:Will “Too Big To Fail” Prevail? Adrian van Rixtela, Yupana Wiwattanakantangb, Toshiyuki Soumac and Kazunori Suzukid a European Central Bank, Postfach 16 03 19, D-60066 Frankfurt am Main GERMANY b Center for Center for Economic Institutions, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, 2-1 Naka, Kunitachi, Tokyo 186-8603, JAPAN c Faculty of Economics, Kyoto Gakuen University, Nanjo, Sogabe-cho, Kameoka, Kyoto 621-8555, JAPAN d Professor of Finance, Graduate School of International Accounting Chuo University Room 1556, 42-8, Ichigaya-Honmuracho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-0845, JAPAN Abstract This paper reviews the evolution of the Japanese banking sector and the development of the banking crisis in Japan in the context of “too big to fail.” It describes the deterioration of the Japanese financial sector caused by the bad loan problems and the failure of policymakers to get a grip on the underlying problems. -

The Performance and Roles of Japanese Development Banks

THE PERFORMANCE AND ROLES OF JAPANESE DEVELOPMENT BANKS Ayako Yasuda Department of Economics Stanford University May 1993 * This paper was written as a Senior Honors Thesis in Fall '92 - Spring 93. The author is much indebted to Dr. Marilou Uy, Professor Joseph E. Stiglitz, Dr. John Page, and Ms. Maria-Louisa Cicognani for their guidance and support during my internship at the World Bank, and to Professor Masahiko Aoki of Stanford University for his mentorship throughout the school year. She is also grateful to Professor Hugh Patrick and Mr. Frank Packer for their comments on an earlier version of the paper. THE PERFORMANCE AND ROLES OF JAPANESE DEVELOPMENT BANKS TABLE OF CONTENTS 31. -D EVUUTION OF' DEWTI- IN JAPm 2.1 The Status of Development Banks within the Japanese Banking System 2.1.1 Identification of Development Banks in Japan 2.1.2 Development Banks in Relation to ~inancialSystem in Japan 2.1.3 Market Shares of JDB and IBJ in Long-Term Loan Market 2.2 J.P. Morgan of Japan? ----Origins of IBJ in the Pre-War Period 2.3 Changes in the Financial System during the War Period and Subsequent Change in IBJ1s Role 2.4 Origins of Post-War Long-Term Financial Institutions -$GES. -$GES. I AND PERFORMANCE 3.1 Privileges Given to and Restrictions Imposed upon the Japanese Development Banks 3.2 Direction of Loans Made by the Japanese Development Banks in Post- War High-Growth Period -IV. HYPOTHESES CONCERNING THE ACTUAL ROLES PLAYED BY THE JAPANESE 4.1 Insurance Effect and Signaling Effect 4.2 Complementarities among City Banks, JDB, and IBJ 4.3 Coordinating / Communicational Roles Of Neutral Players 4.4 IBJ as Prototype of a Main Bank WWOPmNTVTW T BANKS IN DEWTIOPING COUNTRIES AND TRANSFORMING SOCIALIST ECONOMIES 5.1 The Existing Problems with Banking Sector in Other Countries 5.2 JDB-Type Bank and/or IBJ-Type Bank-: Prerequisites, Benefits, and Problems VI. -

Takeo Hoshi Anil Kashyap

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE JAPANESE BANKING CRISIS: WHERE DID IT COME FROM AND HOW WILL IT END? Takeo Hoshi Anil Kashyap Working Paper 7250 http://www.nber.org/papers/w7250 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 1999 We thank Ben Bernanke, Ricardo Caballero, Menzie Chin, Peter Cowhey, Mitsuhiro Fukao, Mark Gertler, Peter Gourevitch, Yasushi Hamao, Masahiro Higo, Michael Hutchison, Tomohiro Kinoshita, Hugh Patrick, Joe Peek, Julio Rotemberg, Ross Starr, Robert Uriu, and Yaacov Vertzberger along with the participants of the presentations at University of Chicago, Graduate School of Business Brown Bag lunch, the NBER Japan Group, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of Italy, UCLA conference on the "Political Economy of the Japanese Financial Crisis", Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and IR/PS at University of California, San Diego for helpful comments. We thank Raghu Rajan for providing data from National Survey of Small Business Finance, Itsuko Takemura from the Institute of Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Japanese Ministry of Finance for providing data from Hojin Kigyo Tokei, and Simon Gilchrist, Kenji Hayashi, and Sumio Saruyama for helping us with other data issues. We thank Fernando Avalos, Yumiko Ito, Jolm McNulty, and Motoki Yanase for excellent research assistance. Kashyap's work was supported through a grant from the National Science Foundation to the National Bureau of Economic Research. Hoshi's work was supported by a grant from Tokyo Center for Economic Research. Forthcoming in the NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1999. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Federal Reserve System, or the National Bureau of Economic Research.