Is the Distance to Default a Good Measure in Predicting Bank Failures? Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

Regional Banks in Japan 2008

Regional Banks in Japan 2008 We, the 64 regional banks in Japan, have for a long time enjoyed the patronage of the people of our regions as banks that move in step with the community. Hokkaido The Hokkaido Bank The regional banks as financial institutions that have the trust of their customers, will continue to contribute to the activation of regional societies through meeting various financial needs in the regions, by enhancing financial functions such as relationship- based banking. Aomori The Aomori Bank THE MICHINOKU BANK Akita Iwate THE AKITA BANK The Bank of Iwate The Hokuto Bank THE TOHOKU BANK Yamagata THE SHONAI BANK The Yamagata Bank Miyagi The 77 Bank Niigata The Daishi Bank Fukushima The Hokuetsu Bank The Toho Bank Ishikawa Toyama The Hokkoku Bank The Hokuriku Bank THE TOYAMA BANK Tochigi Gunma The Ashikaga Bank Tottori Fukui Nagano The Gunma Bank Ibaraki The Hachijuni Bank The Joyo Bank Shimane THE TOTTORI BANK The Fukui Bank Gifu The San-in Godo Bank Kyoto Saitama The Kanto Tsukuba Bank The Ogaki Kyoritsu Bank The Musashino Bank Hyogo The Bank of Kyoto The Juroku Bank Okayama The Tajima Bank Tokyo Shiga Hiroshima The Chugoku Bank The Tokyo Tomin Bank Fukuoka Yamaguchi The Hiroshima Bank Osaka THE SHIGA BANK Chiba THE BANK OF FUKUOKA The Yamaguchi Bank The Kinki Osaka Bank Aichi The Chikuho Bank The Senshu Bank The Chiba Bank THE NISHI-NIPPON CITY BANK Kagawa The Bank of Ikeda The Chiba Kogyo Bank Saga Ehime The Hyakujushi Bank Mie THE BANK OF SAGA Oita The Iyo Bank The Mie Bank Tokushima Nara THE OITA BANK The Hyakugo Bank -

【Major Bank】都市銀行 【Local Bank】地方銀行 【Second Regional

【Major bank】都市銀行 Mizuho Bank / Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation / Saitama Resona Bank Mitsubishi UFJ Bank / Resona Bank (5 in total) 【Local bank】地方銀行 Hokkaido Bank / Yamanashi Central Bank /Saningodo Bank Aomori Bank / Hachijuni Bank / Chugoku Bank Michinoku Bank / Hokuriku Bank /Hiroshima Bank Akita Bank / Toyama Bank / Yamaguchi Bank Hokuto Bank / Hokkoku Bank/ Awa Bank Shonai Bank / Fukui Bank/ Hyakujuyon Bank Yamagata Bank / Shizuoka Bank / Iyo Bank Iwate Bank / Suruga Bank/ Shikoku Bank Tohoku Bank / Shimizu Bank / Fukuoka Bank ShichijushichiBank / Ogaki Kyoritsu Bank / Chikuho Bank Toho Bank / Juroku Bank / Saga Bank Gunma Bank Mie Bank Juhachi Bank Ashikaga Bank / Hyakugo Bank / Shinwa Bank Joyo Bank / Shiga Bank Higo Bank Tsukuba Bank Kyoto Bank Oita Bank Musashino Bank / Kansai Mirai Bank / Miyazaki Bank Chiba Bank / IkedaSenshu Bank / Kagoshima Bank Chiba Kogyo Bank / Nanto Bank /Ryukyu Bank Yokohama Bank / Kiyo Bank / Okinawa Bank Daiyon Bank / Tajima Bank / Nishinihon City Bank HuKuetsu Bank / Tottori bank / Kitakyushu Bank (63 in total) 【Second Regional Bank Member Bank】第二地銀協加盟銀行 Hokuyo Bank Daiko Bank Shimane Bank Kirayaka Bank Nagano Bank Tomato Bank Kitanihon Bank Toyama Daiichi Bank Momiji Bank Sendai Bank Shizuokachuo Bank Saikyo Bank Fukushima Bank Aichi Bank Tokushima Bank Daito Bank Nagoya Bank Kagawa Bank Towa Bank Chukyo Bank Ehime Bank Tochigi Bank Daisan Bank Kochi Bank Tokyo Star Bank Taisho Bank Kumamoto Bank Kanagawa Bank Minato Bank (29 in total) 【Trust bank-Shintaku Ginko】信託銀行 Mitsubishi UFJ Trust Bank -

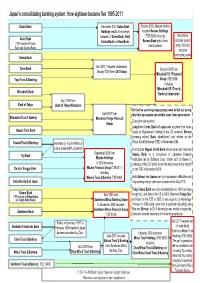

Japanâ••S Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

Japan’s consolidating banking system: How eighteen became five 1995-2013 Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki Red border (TSE 8308) including Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current (1991 merger of Kyowa Osaka Bank and Nara Bank. trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (TSE 8306) Toyo Trust & Banking including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega-groups were bailed out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank, rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due to long-running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group (TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trust & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010. -

Japanese Banks' Monitoring Activities

Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996* Paper Prepared for the CGP Conference Macro/Financial Issues and International Economic Relations: Policy Options for Japan and the United States October 22-23, 2004, Ann Arbor Kyoji Fukao** Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University and RIETI Kiyohiko G. Nishimura Faculty of Economics, University of Tokyo and ESRI, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan Qing-Yuan Sui Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Yokohama City University, Masayo Tomiyama Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University * We are grateful to the participants of the pre-conference meeting of the CGP project and a seminar held at Hitotsubashi University for their comments and suggestions on a preliminary version of this paper. ** Correspondence: Kyoji Fukao, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Naka 2-1, Kunitachi, Tokyo 186-8603 JAPAN. Tel.: +81-42-580-8359, Fax.: +81-42-580-8333, e-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Using micro data of Japanese banks and borrower firms, we construct an index measure that quantitatively describes the monitoring activities of Japanese banks. We examine the effects of bank monitoring on the profitability of borrower firms. We find significant positive effects in the periods 1986-1991 and 1992-1996, although there is no significant effect in the 1981-1985 period . We also examine how banks' monitoring affects borrowers. The results show that the positive effects of banks' monitoring on borrowers' profitability are mostly caused by screening effects, not performance-improving effects. 1 Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996 One of the most dramatic developments in the Japanese economy during the 1990s concerns the fate of the country's banks. -

Does the Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk?: Evidence From

WorkingPaper Series Does The Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk? Evidence from Financial Firm Failures Elijah Brewer III, Hesna Genay, William Curt Hunter and George G. Kaufman Working Papers Series Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago December 1999 (WP-99-31) ,11111 Wifi iiilli™iIIII§«lf III! • FEDERAL RESERVE BANK !!fl!!l!l||ll!illll OF CHICAGO i s Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis DOES THE JAPANESE STOCK MARKET PRICE BANK RISK? EVIDENCE FROM FINANCIAL FIRM FAILURES Elijah Brewer HI* Hesna Genay* William Curt Hunter* George G. Kaufman** December 1999 * Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago ** Loyola University Chicago and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Corresponding author: Hesna Genay, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Economic Research, 230 S. LaSalle Street, Chicago, IL 60604. [email protected]. The research assistance of Scott Briggs, Kenneth Housinger, George Simler, and Alex Urbina is greatly appreciated. The authors also would like to thank Anil Kashyap, participants at the The Sixth Annual Global Finance Conference, The Thirty-Fifth Annual Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, and 1999 FMA Meetings for valuable comments, and Rieko McCarthy of Moody’s Investor Services for the information she so kindly provided. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Federal Reserve System. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ABSTRACT The efficiency of Japanese stock market to appropriately price the riskiness of Japanese firms has been frequently questioned, particularly with respect to Japanese banks which have experienced severe financial distress in recent years. -

Japan's Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

-DSDQVFRQVROLGDWLQJEDQNLQJV\VWHP+RZHLJKWHHQEHFDPHILYH Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki (TSE 8308) including Red border Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current Osaka Bank and Nara Bank . (1991 merger of Kyowa trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Toyo Trust & Banking Group (TSE 8306) including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega -groups were ba iled out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank , rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. to long -running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai -ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group ( TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trus t & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010. -

Japan's First Full-Banking System in the Public Cloud Started Operation at Hokkoku Bank

****************************************************************************************************** This news release is a joint news release issued by The Hokkoku Bank, Ltd., Nihon Unisys, Ltd. and Microsoft Japan, Co., Ltd. Please be advised of multiple deliveries of the same contents. ****************************************************************************************************** The Hokkoku Bank, Ltd. Nihon Unisys, Ltd. Microsoft Japan Co., Ltd. May 6, 2021 Japan’s first full-banking system in the public cloud started operation at Hokkoku Bank ~Promoting the Business Model Reform of Regional Banks through BankVision on Azure The Hokkoku Bank, Ltd. (Head Office: Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture; President: Shuji Tsuemura)and Nihon Unisys Co., Ltd. (Head Office: Koto-ku, Tokyo; President: Akiyoshi Hiraoka) began operating BankVision, an open account system, on Microsoft Azure of the public cloud platform of Microsoft Japan Co., Ltd. (Head Office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; President: Hitoshi Yoshida), on May 3. The full banking system is the first in the country to operate in a public cloud environment. [Background] The Hokkoku Bank aims to become a "next-generation of integrated regional companies," deepening the customer's perspective, deepening communication and collaboration within the bank and with local community, and contributing to the innovation throughout the region. We are promoting the improvement of sales productivity and expansion into new business domains by making good use of IT technologies that are evolving at an accelerating -

International Smallcap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017

International SmallCap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017 SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS MARKET % OF SECURITY SHARES VALUE ASSETS AUSTRALIA INVESTA OFFICE FUND 2,473,742 $ 8,969,266 0.47% DOWNER EDI LTD 1,537,965 $ 7,812,219 0.41% ALUMINA LTD 4,980,762 $ 7,549,549 0.39% BLUESCOPE STEEL LTD 677,708 $ 7,124,620 0.37% SEVEN GROUP HOLDINGS LTD 681,258 $ 6,506,423 0.34% NORTHERN STAR RESOURCES LTD 995,867 $ 3,520,779 0.18% DOWNER EDI LTD 119,088 $ 604,917 0.03% TABCORP HOLDINGS LTD 162,980 $ 543,462 0.03% CENTAMIN EGYPT LTD 240,680 $ 527,481 0.03% ORORA LTD 234,345 $ 516,380 0.03% ANSELL LTD 28,800 $ 504,978 0.03% ILUKA RESOURCES LTD 67,000 $ 482,693 0.03% NIB HOLDINGS LTD 99,941 $ 458,176 0.02% JB HI-FI LTD 21,914 $ 454,940 0.02% SPARK INFRASTRUCTURE GROUP 214,049 $ 427,642 0.02% SIMS METAL MANAGEMENT LTD 33,123 $ 410,590 0.02% DULUXGROUP LTD 77,229 $ 406,376 0.02% PRIMARY HEALTH CARE LTD 148,843 $ 402,474 0.02% METCASH LTD 191,136 $ 399,917 0.02% IOOF HOLDINGS LTD 48,732 $ 390,666 0.02% OZ MINERALS LTD 57,242 $ 381,763 0.02% WORLEYPARSON LTD 39,819 $ 375,028 0.02% LINK ADMINISTRATION HOLDINGS 60,870 $ 374,480 0.02% CARSALES.COM AU LTD 37,481 $ 369,611 0.02% ADELAIDE BRIGHTON LTD 80,460 $ 361,322 0.02% IRESS LIMITED 33,454 $ 344,683 0.02% QUBE HOLDINGS LTD 152,619 $ 323,777 0.02% GRAINCORP LTD 45,577 $ 317,565 0.02% Not FDIC or NCUA Insured PQ 1041 May Lose Value, Not a Deposit, No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee 07-17 Not Insured by any Federal Government Agency Informational data only. -

Role of JSCC in Japan's Securities Market

JAPAN'SJAPAN'S LEADINGLEADING CLEARINGCLEARING HOUSEHOUSE Annual Report 2008 FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 2008 Profile Japan Securities Clearing Corporation (JSCC) is a unified cross-market clearing organization in Japan. Objectives of To improve the efficiency and convenience of the market Incorporation and to ensure safety in settlement. In January 2003, Japan Securities Clearing Corporation (JSCC) was licensed to conduct the Securities Obligation Assumption Business (current Financial Instruments Obligation Assumption Business based on the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act) for the first time in Japan and commenced its operations. The birth of JSCC has led to dramatic improvements in the efficiency and convenience of the securities market by consolidating the clearing of securities transactions that used to be performed separately by individual markets. In addition, JSCC is entrusted by other clearing organizations with the task of monitoring the financial standing of clearing participants. This enables the consolidation of the liaison channels of participants. JSCC strives to improve convenience and contribute to the efficient operation of clearing organizations through such arrangement. Corporate We endeavor to enhance the competitiveness of Japanese securities and Philosophy derivatives markets by improving the efficiency, convenience and safety in post-trade processing infrastructure. Based on its corporate philosophy as shown above, JSCC is committed to continue providing the infrastructure for clearing and settlements for -

Karafuto 1945: an Examination of the Japanese Under Soviet Rule and Their Subsequent Expulsion

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-21-2015 Karafuto 1945: An examination of the Japanese under Soviet rule and their subsequent expulsion Cameron Carson Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Carson, Cameron, "Karafuto 1945: An examination of the Japanese under Soviet rule and their subsequent expulsion" (2015). Honors Theses. 2557. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2557 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Karafuto 1945: An Examination of the Japanese Under Soviet Rule and Their Subsequent Expulsion By Cameron B. Carson 1 Introduction The year 1945 saw the end of the Second World War, which claimed millions of lives from both civilians and members of the military. 1945 was also the beginning of another type of conflict, namely the Cold War, which the USA and USSR fought through proxy and filled both with fear. One of the issues that many historians overlook between the two superpowers is the repatriation of Japanese nationals who were left in a remote part of the former Japanese Empire that fell under the control of the USSR in the closing days of the war. This paper will look at the stories of the Japanese nationals left behind on Sakhalin Island (or “Karafuto” as it was known to the Japanese) after it was invaded and subsequently occupied by the USSR in August 1945. -

Tokyo Stock Exchange Tokyo Stock Exchange

Tokyo Stock Exchange Annual Report 1998 Year Ended March 31, 1998 Profile or almost 120 years, the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) has Fbeen recognized and functioned as Japan’s central stock market. Since its reestablishment in 1949, the TSE has responded positively to trading demands from both overseas and domestic investors, operating both cash and derivatives markets. Now, at the drawn of a new era in which the legal and system- atic framework created by the recent market reforms is taking shape, the TSE is endeavoring to construct and operate a highly efficient and competitive market that will allow it to play a major role in the economic life of Japan, Asia and the world. 3000 2500 2000 1500 CONTENTS Statistical Highlights.....................................3 1000 Message from the President..........................5 TSE Market System.......................................6 Special Feature............................................12 500 Financial Statements...................................14 Board of Governors and Auditors ..............17 List of Members and Special Participants ...20 1970 7172 73 74 75 Statistical Highlights At December 31 1997 1996 1995 (STOCK MARKET) Listed Companies : Domestic .................................................. 1,805 1,766 1,714 : Foreign ..................................................... 60 67 77 Newly Listed Companies : Domestic .................................................. 50 59 32 : Foreign ..................................................... 1 20 Market Value (¥ billions) : Domestic