The Japanese Banking Crisis: Where Did It Come from and How Will It End?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Players in Agricultural Financing (Cont’D)

Table of Contents Abbreviation .............................................................................................................................................................................1 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................................................2 Summary .............................................................................................................................................................................7 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 21 1.1 Background and Purposes of the Study .................................................................................................................. 21 1.2 Study Directions .......................................................................................................................................................... 21 1.3 Study Activities ............................................................................................................................................................ 22 2. Analyses of Financial Systems for Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan ................................................. 23 2.1 Finance Policy and Financial Systems for Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan ...................................... 23 2.2 Financial Systems for Micro, Small -

Measuring the Effect of Postal Saving Privatization on Japanese Banking Industry: Evidence from the 2005 General Election*

Working Paper Series No. 11-01 May 2011 Measuring the effect of postal saving privatization on Japanese banking industry: Evidence from the 2005 general election Michiru Sawada Research Institute of Economic Science College of Economics, Nihon University Measuring the effect of postal saving privatization on Japanese banking * industry: Evidence from the 2005 general election Michiru Sawada** Nihon University College of Economics, Tokyo, Japan Abstract In this study, we empirically investigate the effect of the privatization of Japan’s postal savings system, the world’s largest financial institution, on the country’s banking industry on the basis of the general election to the House of Representatives on September 11, 2005—essentially a referendum on the privatization of the postal system. Econometric results show that the privatization of postal savings system significantly raised the wealth of mega banks but not that of regional banks. Furthermore, it increased the risk of all categories of banks, and the banks that were dependent on personal loans increased their risk in response to the privatization of postal savings. These results suggest that incumbent private banks might seek new business or give loans to riskier customers whom they had not entertained before the privatization, to gear up for the new entry of Japan Post Bank (JPB), the newly privatized institution, into the market for personal loans. Hence, privatization of postal savings system probably boosted competition in the Japanese banking sector. JEL Classification: G14, G21, G28 Keywords: Bank privatization, Postal savings system, Rival’s reaction, Japan * I would like to thank Professor Sumio Hirose, Masaru Inaba, Sinjiro Miyazawa, Yoshihiro Ohashi, Ryoko Oki and Daisuke Tsuruta for their helpful comments and suggestions. -

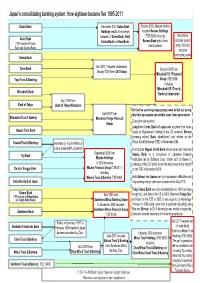

Japanâ••S Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

Japan’s consolidating banking system: How eighteen became five 1995-2013 Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki Red border (TSE 8308) including Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current (1991 merger of Kyowa Osaka Bank and Nara Bank. trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (TSE 8306) Toyo Trust & Banking including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega-groups were bailed out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank, rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due to long-running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group (TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trust & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010. -

Japanese Banks' Monitoring Activities

Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996* Paper Prepared for the CGP Conference Macro/Financial Issues and International Economic Relations: Policy Options for Japan and the United States October 22-23, 2004, Ann Arbor Kyoji Fukao** Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University and RIETI Kiyohiko G. Nishimura Faculty of Economics, University of Tokyo and ESRI, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan Qing-Yuan Sui Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Yokohama City University, Masayo Tomiyama Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University * We are grateful to the participants of the pre-conference meeting of the CGP project and a seminar held at Hitotsubashi University for their comments and suggestions on a preliminary version of this paper. ** Correspondence: Kyoji Fukao, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Naka 2-1, Kunitachi, Tokyo 186-8603 JAPAN. Tel.: +81-42-580-8359, Fax.: +81-42-580-8333, e-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Using micro data of Japanese banks and borrower firms, we construct an index measure that quantitatively describes the monitoring activities of Japanese banks. We examine the effects of bank monitoring on the profitability of borrower firms. We find significant positive effects in the periods 1986-1991 and 1992-1996, although there is no significant effect in the 1981-1985 period . We also examine how banks' monitoring affects borrowers. The results show that the positive effects of banks' monitoring on borrowers' profitability are mostly caused by screening effects, not performance-improving effects. 1 Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996 One of the most dramatic developments in the Japanese economy during the 1990s concerns the fate of the country's banks. -

Does the Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk?: Evidence From

WorkingPaper Series Does The Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk? Evidence from Financial Firm Failures Elijah Brewer III, Hesna Genay, William Curt Hunter and George G. Kaufman Working Papers Series Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago December 1999 (WP-99-31) ,11111 Wifi iiilli™iIIII§«lf III! • FEDERAL RESERVE BANK !!fl!!l!l||ll!illll OF CHICAGO i s Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis DOES THE JAPANESE STOCK MARKET PRICE BANK RISK? EVIDENCE FROM FINANCIAL FIRM FAILURES Elijah Brewer HI* Hesna Genay* William Curt Hunter* George G. Kaufman** December 1999 * Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago ** Loyola University Chicago and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Corresponding author: Hesna Genay, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Economic Research, 230 S. LaSalle Street, Chicago, IL 60604. [email protected]. The research assistance of Scott Briggs, Kenneth Housinger, George Simler, and Alex Urbina is greatly appreciated. The authors also would like to thank Anil Kashyap, participants at the The Sixth Annual Global Finance Conference, The Thirty-Fifth Annual Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, and 1999 FMA Meetings for valuable comments, and Rieko McCarthy of Moody’s Investor Services for the information she so kindly provided. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Federal Reserve System. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ABSTRACT The efficiency of Japanese stock market to appropriately price the riskiness of Japanese firms has been frequently questioned, particularly with respect to Japanese banks which have experienced severe financial distress in recent years. -

Japan's Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

-DSDQVFRQVROLGDWLQJEDQNLQJV\VWHP+RZHLJKWHHQEHFDPHILYH Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki (TSE 8308) including Red border Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current Osaka Bank and Nara Bank . (1991 merger of Kyowa trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Toyo Trust & Banking Group (TSE 8306) including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega -groups were ba iled out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank , rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. to long -running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai -ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group ( TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trus t & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010. -

Taipei,China's Banking Problems: Lessons from the Japanese Experience

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Montgomery, Heather Working Paper Taipei,China's Banking Problems: Lessons from the Japanese Experience ADBI Research Paper Series, No. 42 Provided in Cooperation with: Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo Suggested Citation: Montgomery, Heather (2002) : Taipei,China's Banking Problems: Lessons from the Japanese Experience, ADBI Research Paper Series, No. 42, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo, http://hdl.handle.net/11540/4148 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/111142 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/ www.econstor.eu ADB INSTITUTE RESEARCH PAPER 42 Taipei,China’s Banking Problems: Lessons from the Japanese Experience Heather Montgomery September 2002 Over the past decade, the health of the banking sector in Taipei,China has been in decline. -

Kabushiki Kaisha Mizuho Financial Group (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) Mizuho Financial Group, Inc

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2012 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-33098 Kabushiki Kaisha Mizuho Financial Group (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Mizuho Financial Group, Inc. (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 5-1, Marunouchi 2-chome Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8333 Japan (Address of principal executive offices) Hisaaki Hirama, +81-3-5224-1111, +81-3-5224-1059, address is same as above (Name, Telephone, Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, without par value The New York Stock Exchange* American depositary shares, each of which represents two shares of The New York Stock Exchange common stock Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Project Daedalus, by Thomas Hoover This Ebook Is for the Use of Anyone Anywhere at No Cost and Wi

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Project Daedalus, by Thomas Hoover This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Title: Project Daedalus Author: Thomas Hoover Release Date: November 14, 2010 [EBook #34320] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PROJECT DAEDALUS *** Produced by Al Haines ============================================================== This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License, http://creativecommons.org/ ============================================================== PROJECT DAEDALUS Retired agent Michael Vance is approached for help on the same day by an old KGB adversary and a brilliant and beautiful NSA code breaker. While their problems seem at first glance to be different, Vance soon learns he’s got a potentially lethal tiger by the tail – a Japanese tiger. A secret agreement between a breakaway wing of the Russian military and the Yakuza, the Japanese crime lords, bears the potential to shift the balance or world power. The catalyst is a superplane that skims the edge of space – the ultimate in death-dealing potential. In a desperate union with an international force of intelligence mavericks, with megabillions and global supremacy at stake, Vance has only a few days to bring down a conspiracy that threatens to ignite nuclear Armageddon. Publisher’s Weekly “Hoover’s adept handling of convincing detail enhances this entertaining thriller as his characters deal and double-deal their way through settings ranging from the Acropolis to the inside of a spacecraft. -

Karafuto 1945: an Examination of the Japanese Under Soviet Rule and Their Subsequent Expulsion

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-21-2015 Karafuto 1945: An examination of the Japanese under Soviet rule and their subsequent expulsion Cameron Carson Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Carson, Cameron, "Karafuto 1945: An examination of the Japanese under Soviet rule and their subsequent expulsion" (2015). Honors Theses. 2557. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2557 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Karafuto 1945: An Examination of the Japanese Under Soviet Rule and Their Subsequent Expulsion By Cameron B. Carson 1 Introduction The year 1945 saw the end of the Second World War, which claimed millions of lives from both civilians and members of the military. 1945 was also the beginning of another type of conflict, namely the Cold War, which the USA and USSR fought through proxy and filled both with fear. One of the issues that many historians overlook between the two superpowers is the repatriation of Japanese nationals who were left in a remote part of the former Japanese Empire that fell under the control of the USSR in the closing days of the war. This paper will look at the stories of the Japanese nationals left behind on Sakhalin Island (or “Karafuto” as it was known to the Japanese) after it was invaded and subsequently occupied by the USSR in August 1945. -

Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation

Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (incorporated under the laws of Japan with limited liability) U.S.$1,350,000,000 Fixed to Floating Rate Perpetual Subordinated Bonds 4700,000,000 Fixed to Floating Rate Perpetual Subordinated Bonds The Initial Purchasers are offering U.S.$1,350,000,000 aggregate principal amount of Fixed to Floating Rate Perpetual Subordinated Bonds (the ‘‘Dollar Bonds’’) and 4700,000,000 aggregate principal amount of Fixed to Floating Rate Perpetual Subordinated Bonds (the ‘‘Euro Bonds’’, and together with the Dollar Bonds, the ‘‘Bonds’’) of Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (‘‘SMBC’’ or the ‘‘Bank’’) outside the United States only to non-U.S. Persons in reliance on Regulation S (‘‘Regulation S’’) under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the ‘‘Securities Act’’). In addition, the Initial Purchasers, through their respective selling agents, are offering the Bonds inside the United States to qualified institutional buyers (‘‘QIBs’’ or ‘‘qualified institutional buyers’’) in reliance on Rule 144A (‘‘Rule 144A’’) under the Securities Act. Approval in principle has been received for listing of the Bonds on the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited (the ‘‘SGX-ST’’). The listing of the Bonds on the SGX-ST is not to be taken as an indication of the merits of the Bonds or SMBC. The SGX-ST takes no responsibility for the correctness of any of the statements made or opinions or reports contained in this Offering Circular. Interest on the Dollar Bonds will accrue from their date of initial issuance and be payable semi-annually in arrears on April 15 and October 15 in each year, commencing on October 15, 2005, until October 15, 2015, and thereafter quarterly in arrears on January 15, April 15, July 15 and October 15 in each year. -

J Trust Co., Ltd. (8508 TSE2) Issue Date: October 6, 2015

ANALYST NET Company Report J Trust Co., Ltd. (8508 TSE2) Issue Date: October 6, 2015 Transitioning main source of profit from domestic business to overseas businsss and turning around financial business in South Korea Independent financial group known as "JT" with prominent Basic Report position in South Korea and Southeast Asia (FY2016-3, 1st Quarter) J Trust Co., Ltd. is an independent financial group known by sponsorship to Takefuji and the acquisition of KC Card. Current core businesses are: (i) domestic SQUADD Research & Consulting, Inc. financial business centered on credit guarantee, (ii) savings bank business in South Tomoko Okuyama / Sadao Korea and (iii) commercial banking business in Indonesia J Trust may not be well Sakamoto known in Japan, but is broadly recognized as "JT" ("J TRUST") in the Southeast Asia region, particularly in South Korea and Indonesia. After TOB by Nobuyoshi Fujisawa (current CEO), it has rapidly expanded the business scale through M&A, Company Information and as a result, total assets surged from c.12.2 billion yen to c. 540.7 billion yen Name J Trust Co.,Ltd. (c.44-fold increase) and operating revenue increased rapidly from c.3.2 billion yen to c. 63.3 billion yen (about 20-fold increase) over about seven years. While it has Equity Code 8508 accumulated assets primarily through M&A in Japan over several years after TOB, it Market Section TSE's 2nd Section has looked into tie-up with banks in the domestic business (credit guarantee, etc.) Location Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo from the early stage, and promoted M&A strategies under the mid- to long-term President Nobuyoshi Fujisawa vision to develop retail banking business in Asia.