Takeo Hoshi Anil Kashyap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Report –Annual Review– Integrated Report 2017 –Annual Review– April 2016 – March 2017 Our Corporate Philosophy

Mizuho Financial Group Mizuho Financial Group | 2017 Integrated Report –Annual Review– Integrated Report 2017 –Annual Review– April 2016 – March 2017 Our Corporate Philosophy Mizuho, the leading Japanese financial services group with a global presence and a broad customer base, is committed to: Providing customers worldwide with the highest quality financial services with honesty and integrity; Anticipating new trends on the world stage; Expanding our knowledge in order to help customers shape their future; Growing together with our customers in a stable and sustainable manner; and Bringing together our group–wide expertise to contribute to the prosperity of economies and societies throughout the world. These fundamental commitments support our primary role in bringing fruitfulness for each customer and the economies and the societies in which we operate. Mizuho creates lasting value. It is what makes us invaluable. Corporate Philosophy: Mizuho’s The Mizuho Values fundamental approach to business Customer First: activities, based on the The most trusted partner lighting raison d’etre of Mizuho the future Innovative Spirit: Vision: Progressive and flexible thinking Mizuho’s vision for Mizuho’s Corporate Identity Mizuho’s the future, realized Team Spirit: through the practice of Diversity and collective strength “Corporate Philosophy” Speed: Acuity and promptness The Mizuho Values: The shared values and principles of Passion: Mizuho’s people, uniting all executives and Communication and challenge for employees together to pursue “Vision” the future 1 Mizuho Financial Group The most trusted financial services group with a global presence and a broad customer base, contributing to the prosperity of the world, Asia, and Japan 2017 Integrated Report 2 Editorial Policy Contents This Integrated Report includes financial information as well as non-financial information on such subjects as ESG. -

To Our Shareholders and Customers Issues We Faceinfiscal2000

To Our Shareholders and Customers — The Dawn of a New Era — Review of Fiscal 1999 For the Japanese financial sector, fiscal 1999 During fiscal 1999, we strengthened our man- marked the start of a totally new era in the his- agement infrastructure and corporate structure tory of finance in Japan. by improving business performance, restructur- In August 1999, The Fuji Bank, Limited, ing operations, strengthening risk management The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, Limited, and The and managing consolidated business activities Industrial Bank of Japan, Limited, reached full under a stronger group strategy. agreement to consolidate their operations into a comprehensive financial services group to be • Improving Business Performance called the Mizuho Financial Group. In the fol- We have identified the domestic corporate and lowing six months after the announcement, retail markets as our priority business areas. several other major Japanese financial institu- Our goals in these markets are to enhance our tions announced mergers and consolidations of products and services to meet the wide-ranging one form or another. needs of our customers, and to improve cus- At the same time, conditions in the financial tomer convenience by using information tech- sector changed dramatically as foreign-owned nology to diversify our service channels. financial institutions began in earnest to With respect to enhancing products and expand their presence in Japan, companies services, we focused on services provided to from other sectors started to move into the members of the Fuji First Club, a membership To Our Shareholders and Customers To financial business, and a number of Internet- reward program that offers special benefits to based strategic alliances were formed across dif- member customers, and on our product lineup ferent sectors and industries. -

The Corporate Culture in a Japanese Bank: Study of the Changing Organizational World

The Corporate Culture in a Japanese Bank: Study of the Changing Organizational World by HIROFUMI HOJO B.A. Law, Keio University (1986) SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2005 © Hirofumi Hojo 2005. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. ^ /' Ar Signature of Author: 'I (! J MIT SloVn School of Management May 6, 2005 Certified by: I John E. Van Maanen Erwin H. Schell Professor of Organization Studies Thesis Advisor Accepted by: / I I , / Stephen J. Sacca Director, Sloan Fellows Program in Innovation and Global Leadership lMASSACHUSETSINSTITE OF TECHNOLOGY 'A I IX~IFtes SEP 012005 LIBRARIES 2 The Corporate Culture in a Japanese Bank: Study of the Changing Organizational World by HIROFUMI HOJO Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management on May 6, 2005 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Management ABSTRACT The environment surrounding companies is constantly changing. and that change forces companies into paradigm shifts. If a company cannot cope with change, it faces the distinct possibility of being be weeded out of the industry. Today, Japanese companies are facing dramatic environmental change. For example, the introduction of new global accounting rules is changing the behavior of equity holders. The long and deep recession following the collapse of the Japanese "bubble" economy continues to sap the economic energy of many Japanese companies, and most leaders of those companies still struggle to find new ways to exit from this dark tunnel. -

Players in Agricultural Financing (Cont’D)

Table of Contents Abbreviation .............................................................................................................................................................................1 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................................................2 Summary .............................................................................................................................................................................7 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 21 1.1 Background and Purposes of the Study .................................................................................................................. 21 1.2 Study Directions .......................................................................................................................................................... 21 1.3 Study Activities ............................................................................................................................................................ 22 2. Analyses of Financial Systems for Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan ................................................. 23 2.1 Finance Policy and Financial Systems for Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan ...................................... 23 2.2 Financial Systems for Micro, Small -

Measuring the Effect of Postal Saving Privatization on Japanese Banking Industry: Evidence from the 2005 General Election*

Working Paper Series No. 11-01 May 2011 Measuring the effect of postal saving privatization on Japanese banking industry: Evidence from the 2005 general election Michiru Sawada Research Institute of Economic Science College of Economics, Nihon University Measuring the effect of postal saving privatization on Japanese banking * industry: Evidence from the 2005 general election Michiru Sawada** Nihon University College of Economics, Tokyo, Japan Abstract In this study, we empirically investigate the effect of the privatization of Japan’s postal savings system, the world’s largest financial institution, on the country’s banking industry on the basis of the general election to the House of Representatives on September 11, 2005—essentially a referendum on the privatization of the postal system. Econometric results show that the privatization of postal savings system significantly raised the wealth of mega banks but not that of regional banks. Furthermore, it increased the risk of all categories of banks, and the banks that were dependent on personal loans increased their risk in response to the privatization of postal savings. These results suggest that incumbent private banks might seek new business or give loans to riskier customers whom they had not entertained before the privatization, to gear up for the new entry of Japan Post Bank (JPB), the newly privatized institution, into the market for personal loans. Hence, privatization of postal savings system probably boosted competition in the Japanese banking sector. JEL Classification: G14, G21, G28 Keywords: Bank privatization, Postal savings system, Rival’s reaction, Japan * I would like to thank Professor Sumio Hirose, Masaru Inaba, Sinjiro Miyazawa, Yoshihiro Ohashi, Ryoko Oki and Daisuke Tsuruta for their helpful comments and suggestions. -

Corporate Matching Gifts

Corporate Matching Gifts Your employer may match your contribution. The Corporations listed below have made charitable contributions, through their Matching Gift Programs, for educational, humanitarian and charitable endeavors in years past. Some Corporations require that you select a particular ministry to support. A K A. E. Staley Manufacturing Co. Kansas Gty Southern Industries Inc Abbott Laboratories Kemper Insurance Cos. Adams Harkness & Hill Inc. Kemper National Co. ADC Telecommunications Kennametal Inc. ADP Foundation KeyCorp Adobe Systems, Inc. Keystone Associates Inc. Aetna Inc. Kimberly Clark Foundation AG Communications Systems Kmart Corp. Aid Association for Lutherans KN Energy Inc. Aileen S. Andrew Foundation Air Products and Chemicals Inc. L Albemarle Corp. Lam Research Corp. Alco Standard Fdn Lamson & Sessions Co. Alexander & Baldwin Inc. LandAmerica Financial Group Inc. Alexander Haas Martin & Partners Leo Burnett Co. Inc. Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Levi Strauss & Co. Allegro MicroSystems W.G. Inc. LEXIS-NEXIS Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Lexmark Internaional Inc. Alliance Capital Management, LP Thomas J. Lipton Co. Alliant Techsystems Liz Claiborne Inc. AlliedSignal Inc. Loews Corp. American Express Co. Lorillard Tobacco Co. American General Corp. Lotus Development Corp. American Honda Motor Co. Inc. Lubrizol Corp. American Inter Group Lucent Technologies American International Group Inc. American National Bank & Trust Co. of Chicago M American Stock Exchange Maclean-Fogg Co. Ameritech Corp. Maguire Oil Co. Amgen In c. Mallinckrodt Group Inc. AmSouth BanCorp. Foundation Management Compensation AMSTED Industries Inc. Group/Dulworth Inc. Analog Devices Inc. Maritz Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. Massachusetts Mutual Life Andersons Inc. Massachusetts Financial Services Investment Aon Corp. Management Archer Daniels Midland Massachusetts Port Authority ARCO MassMutual-Blue Chip Co. -

Annual Report 2017 for the Year Ended March 31, 2017 from a Company Making Things, to a Company Making People Smile

Annual Report 2017 For the year ended March 31, 2017 From a company making things, to a company making people smile. Just a glance at our vehicles and you can imagine days filled with excitement. Just a glimpse of jet wings above and you can envision worlds yet unseen. But no matter the time or place, we are always by our customers’ sides. What is important is not how many cars we make, but how many smiles we can create. More than a century has passed since the founding of Aircraft Research Laboratory, the forerunner of SUBARU. Now, Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd. has been reborn as SUBARU CORPORATION. From making things to delivering value that shines in people’s hearts, SUBARU aims to touch the hearts of people and bring smiles to their faces. We constantly challenge ourselves to ensure that satisfaction with SUBARU is reflected in the happy faces of our customers. SUBARU CORPORATION 01 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 SUBARU CORPORATION 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Vision for 2020 Not big in size, but a high-quality company with distinctive strengths For SUBARU, by no means a large automaker, the two strategies of uncompromising differentiation and added-value are essential for achieving sustained growth in a fierce competitive environment. We will narrow our focus to categories and markets in which we can leverage our strengths, practice selection and concentration in allocation of limited management resources, and further accelerate two initiatives: enhancing the SUBARU brand and building a strong business structure. And, we will seek to have a prominent presence in customers’ minds. -

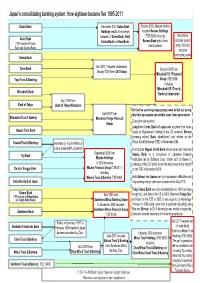

Japanâ••S Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

Japan’s consolidating banking system: How eighteen became five 1995-2013 Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki Red border (TSE 8308) including Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current (1991 merger of Kyowa Osaka Bank and Nara Bank. trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (TSE 8306) Toyo Trust & Banking including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega-groups were bailed out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank, rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due to long-running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group (TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trust & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010. -

Hiroshi Komiyama · Koichi Yamada a Platinum Society

Science for Sustainable Societies Hiroshi Komiyama · Koichi Yamada New Vision 2050 A Platinum Society Science for Sustainable Societies Series Editorial Board Editor in Chief Kazuhiko Takeuchi, Ph.D., Director and Project Professor, Integrated Research System for Sustainability Science (IR3S), The University of Tokyo Institutes for Advanced Study (UTIAS), Chair of the Board of Directors, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan Series Adviser Joanne M. Kauffman, Ph.D., Co-editor in Chief, Handbook of Sustainable Engineering, Springer, 2013 Scientific Advisory Committee Sir Partha Dasgupta, Ph.D., Frank Ramsey Professor Emeritus of Economics, University of Cambridge, UK; Volvo Environment Prize, 2002; Blue Planet Prize, 2015 Hiroshi Komiyama, Ph.D., Chairman, Mitsubishi Research Institute, Japan; President Emeritus, The University of Tokyo, Japan Sander Van der Leeuw, Ph.D., Foundation Professor, School of Human Evolution and Social Change and School of Sustainability, Arizona State University, USA Hiroyuki Yoshikawa, Dr. Eng., Member of Japan Academy; Chairman, The Japan Prize Foundation; President Emeritus, The University of Tokyo, Japan; Japan Prize 1997 Tan Sri Zakri Abdul Hamid, Ph.D., Science Adviser to the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Malaysia; Founding Chair of the UN Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES); Zayed International Prize, 2014 Editorial Board Jean-Louis Armand, Ph.D., Professor, Aix-Marseille Université, France James Buizer, Professor, University of -

Japanese Banks' Monitoring Activities

Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996* Paper Prepared for the CGP Conference Macro/Financial Issues and International Economic Relations: Policy Options for Japan and the United States October 22-23, 2004, Ann Arbor Kyoji Fukao** Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University and RIETI Kiyohiko G. Nishimura Faculty of Economics, University of Tokyo and ESRI, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan Qing-Yuan Sui Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Yokohama City University, Masayo Tomiyama Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University * We are grateful to the participants of the pre-conference meeting of the CGP project and a seminar held at Hitotsubashi University for their comments and suggestions on a preliminary version of this paper. ** Correspondence: Kyoji Fukao, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Naka 2-1, Kunitachi, Tokyo 186-8603 JAPAN. Tel.: +81-42-580-8359, Fax.: +81-42-580-8333, e-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Using micro data of Japanese banks and borrower firms, we construct an index measure that quantitatively describes the monitoring activities of Japanese banks. We examine the effects of bank monitoring on the profitability of borrower firms. We find significant positive effects in the periods 1986-1991 and 1992-1996, although there is no significant effect in the 1981-1985 period . We also examine how banks' monitoring affects borrowers. The results show that the positive effects of banks' monitoring on borrowers' profitability are mostly caused by screening effects, not performance-improving effects. 1 Japanese Banks’ Monitoring Activities and the Performance of Borrower Firms: 1981-1996 One of the most dramatic developments in the Japanese economy during the 1990s concerns the fate of the country's banks. -

Does the Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk?: Evidence From

WorkingPaper Series Does The Japanese Stock Market Price Bank Risk? Evidence from Financial Firm Failures Elijah Brewer III, Hesna Genay, William Curt Hunter and George G. Kaufman Working Papers Series Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago December 1999 (WP-99-31) ,11111 Wifi iiilli™iIIII§«lf III! • FEDERAL RESERVE BANK !!fl!!l!l||ll!illll OF CHICAGO i s Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis DOES THE JAPANESE STOCK MARKET PRICE BANK RISK? EVIDENCE FROM FINANCIAL FIRM FAILURES Elijah Brewer HI* Hesna Genay* William Curt Hunter* George G. Kaufman** December 1999 * Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago ** Loyola University Chicago and Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Corresponding author: Hesna Genay, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Economic Research, 230 S. LaSalle Street, Chicago, IL 60604. [email protected]. The research assistance of Scott Briggs, Kenneth Housinger, George Simler, and Alex Urbina is greatly appreciated. The authors also would like to thank Anil Kashyap, participants at the The Sixth Annual Global Finance Conference, The Thirty-Fifth Annual Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, and 1999 FMA Meetings for valuable comments, and Rieko McCarthy of Moody’s Investor Services for the information she so kindly provided. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Federal Reserve System. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ABSTRACT The efficiency of Japanese stock market to appropriately price the riskiness of Japanese firms has been frequently questioned, particularly with respect to Japanese banks which have experienced severe financial distress in recent years. -

Japan's Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

-DSDQVFRQVROLGDWLQJEDQNLQJV\VWHP+RZHLJKWHHQEHFDPHILYH Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki (TSE 8308) including Red border Asahi Bank Resona Bank which does indicates current Osaka Bank and Nara Bank . (1991 merger of Kyowa trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Toyo Trust & Banking Group (TSE 8306) including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega -groups were ba iled out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank , rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. to long -running NPL problems. The troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai -ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group ( TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006. including Both Shinsei and Aozora ran into subsequent difficulties but Mizuho Trus t & Banking (TSE 8404) Industrial Bank of Japan long-running merger talks were abandoned in May 2010.