Equipping Youth with Agripreneurship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Education,Science,Technology And

Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports Structure of Submission QUARTER 3 Performance Report Summary of Vote Performance Cumulative Progress Report for Projects and Programme Quarterly Progress Report for Projects and Programmes QUARTER 4: Workplans for Projects and Programmes Submission Checklist Page 1 Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports QUARTER 3: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution This section provides an overview of Vote expenditure (i) Snapshot of Vote Releases and Expenditures Table V1.1 below summarises cumulative releases and expenditures by the end of the quarter: Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases (i) Excluding Arrears, Taxes Budget by End by End End Mar Released Spent Spent Wage 11.218 9.015 9.015 8.648 80.4% 77.1% 95.9% Recurrent Non Wage 131.229 109.486 108.844 104.885 82.9% 79.9% 96.4% GoU 62.227 41.228 28.424 24.904 45.7% 40.0% 87.6% Development Ext Fin. 200.477 N/A 77.806 77.806 38.8% 38.8% 100.0% GoU Total 204.674 159.728 146.283 138.436 71.5% 67.6% 94.6% Total GoU+Ext Fin. (MTEF) 405.150 N/A 224.089 216.242 55.3% 53.4% 96.5% Arrears 0.642 N/A 0.642 0.553 100.0% 86.1% 86.1% (ii) Arrears and Taxes Taxes** 19.258 N/A 12.804 2.548 66.5% 13.2% 19.9% Total Budget 425.050 159.728 237.535 219.343 55.9% 51.6% 92.3% * Donor expenditure -

THE ROLE of the NATIONAL FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Nafirri) INFORMATION CENTRE in DISSEMINATING INFORMATION to RESEARCHERS and EDUCATORS

THE ROLE OF THE NATIONAL FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (NaFIRRI) INFORMATION CENTRE IN DISSEMINATING INFORMATION TO RESEARCHERS AND EDUCATORS Alice Endra [email protected] National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI) P.O Box 343, Jinja, Uganda 37th IAMSLIC Conference Zanzibar, Tanzania, October 16-20, 2011 Abstract: Information plays a vital role in the day-to-day decision making of a country’s organizations and policy makers. NaFIRRI Information Centre has played a major role in ensuring that scientists and researchers access relevant information to enable them produce quality research products. The paper discusses the role played by E-Board, a locally established network to increase access to information available within the information centre. NaFIRRI electronic board is a LAN based service that was devised to electronically facilitate information dissemination and communication within the institute. The paper looks at the different components of the E-board and the Aqualink program under the information section that was established to disseminate information on biodiversity conservation among school children and teachers. It discusses the success achieved by this program so far. Keywords: information access, information dissemination, Electronic Board, Aqualink program, biodiversity conservation, aquatic sciences. Introduction Information plays a vital role in the day-to-day decision making process of a country’s organization and policy makers. Research has shown that decision makers often adapt their decision strategies to the information environment (Payne, Bettman and Johnson, 1993). Information is needed at all levels and it is the foundation of effective planning and management as long as the information is used and disseminated. NaFIRRI Information Centre has played a major role in ensuring that scientists, technicians and other researchers from the region access relevant information to enable them produce quality research products for effective policy and decision making through its electronic information dissemination infrastructure. -

The Views of Young Farmers Club Members on Their

THE VIEWS OF YOUNG FARMERS CLUB MEMBERS ON THEIR CLUBS’ ACTIVITIES, THEIR CAREER INTERESTS, AND THEIR INTENTIONS TO PURSUE AGRICULTURE-RELATED CAREER PREPARATION AT THE POST-SECONDARY LEVEL: AN EMBEDDED CASE STUDY OF TWO SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN EASTERN UGANDA By STEPHEN CHARLES MUKEMBO Bachelor of Vocational Studies in Agriculture with Education Kyambogo University Kampala, Uganda 2005 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF AGRICULTURE May, 2013 THE VIEWS OF YOUNG FARMERS CLUB MEMBERS ON THEIR CLUBS’ ACTIVITIES, THEIR CAREER INTERESTS, AND THEIR INTENTIONS TO PURSUE AGRICULTURE-RELATED CAREER PREPARATION AT THE POST-SECONDARY LEVEL: AN EMBEDDED CASE STUDY OF TWO SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN EASTERN UGANDA Thesis Approved: Dr. Craig. M. Edwards Thesis Adviser Dr. Shida Henneberry Dr. John Ramsey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my graduate committee: Dr. M. Craig Edwards (Chair), Dr. J. W. Ramsey, and Dr. Shida Henneberry (Head of Department, International Agriculture) for their support, guidance, and encouragement throughout my research, and for contributing to my professional growth. Special thanks go to Dr. Edwards who made a tremendous sacrifice and patience in ensuring that quality work is produced. Dr. Edwards, I am very grateful for the guidance, mentorship, patience, and dedication to this research and towards my professional development. Thank you. Also Dr. Shane Robinson and Bonne Milby, thank you for your guidance and support. To my fellow graduate students Assoumane Maiga and Matofari Fred, thank you for your time, support, and encouragement. -

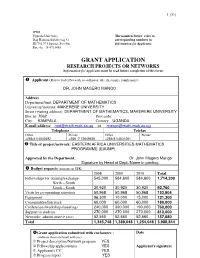

GRANT APPLICATION RESEARCH PROJECTS OR NETWORKS (Information for Applicants Must Be Read Before Completion of This Form)

1 (31) IPMS Uppsala University The numbers below refer to Dag Hammarskjölds väg 31 corresponding numbers in SE 752 37 Uppsala, Sweden Information for Applicants. Fax: 46 - 18 4713495 GRANT APPLICATION RESEARCH PROJECTS OR NETWORKS (Information for Applicants must be read before completion of this form) Applicant (Project leader/Network co-ordinator: title, first name, family name) DR. JOHN MAGERO MANGO Address Department/unit: DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS University/institute: MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Street (visiting address): DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS, MAKERERE UNIVERSITY O Box nr: 7062 Post code: City: KAMPALA Country: UGANDA E-mail address: [email protected] or [email protected] Telephone Telefax Office Private Office Private +256(41)4540692 +256 -7 72649455 +256(41)4531061 Title of project/network: EASTERN AFRICA UNIVERSITIES MATHEMATICS PROGRAMME (EAUMP) Approved by the Department : Dr. John Magero Mango Signature by Head of Dept./Name in printing Budget requests (amounts in SEK) 2008 2009 2010 Total Fellowships for training/exchange 545,000 584,600 584,600 1,714,200 North – South South – South 30,920 30,920 30,920 92,760 Visits by co-operating scientists 50,968 50,968 50,968 152,904 Equipment 96,300 10,000 15,000 121,300 Consumables/literature 60,000 60,000 60,000 180,000 Conferences/workshops/meetings 240,000 330,000 190,000 760,000 Support to students 270,000 270,000 270,000 810,000 Networks: administrative costs 52,560 52,560 52,560 157,680 Total 1,345,748 1,389,048 1,254,048 3,988,844 Grant application submitted with enclosures : Date (indicate those enclosed with yes ) Project description/Network program YES Fellowship application(s) YES Applicant's signature Applicant's CV YES Progress report YES List of publications YES 2 (31) Specification of costs in the first year (2008) Cost (SEK) Total Fellowships for training/exchange North-South Two one month research visits to Sweden 50,000 Support for 7 Ph.D. -

Role of School Based Clubs in Addressing Environmental Threats in the Nile Basin, Case of Jinja District, Uganda

ROLE OF SCHOOL BASED CLUBS IN ADDRESSING ENVIRONMENTAL THREATS IN THE NILE BASIN, CASE OF JINJA DISTRICT, UGANDA BY NDERITU RUTH WANJIRU, B. ENV. (Sc) N50/11294/04 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES (AGROFORESTRY AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT) OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY JUNE 2011 i DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University or for any other award. Signature ………………………… Date ……………………………....... Nderitu, Ruth Wanjiru Department of Environmental Science This thesis has been submitted for examination for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies (Agroforestry and Rural Development) with our approval as University supervisors; Signature ………………………....... Date……………………………….... Dr. Ndaruga, Ayub M. National Environment Management Authority, Kenya Signature …………………………… Date …………………………… Prof. Kungu, James B. Department of Environmental Science Kenyatta University ii DEDICATION Dedicated to my parents, Rev. and Mrs. William Nderitu Maina for moral support and good education iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I appreciate funding from Nile Transboundary Environmental Action Project (NTEAP) to study in Uganda and encouragement from Lily Kisaka and Charles from Kenya office and Maushe Kidundo, from Khartoum NTEAP Office. I acknowledge my supervisors Dr. Ayub Macharia of National Environment Management Authority, Prof. James Kungu of Kenyatta University and Dr. Daniel Babikwa, Makerere University for their support and encouragement. I appreciate officers in the Ministry of Education and Sports, Jinja for allowing me to carry out research, Chairman, Jinja Wildlife Society, Head teachers, patrons, students, National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), Ms Adimola, Director, Environmental Education Department and Monique for literature and moral support. -

TOPIC 1 EARLY HISTORY of EAST AFRICA Who Were the Early

TOPIC 1 EARLY HISTORY OF EAST AFRICA Who were the early inhabitants of the East African coast? 1. Little is known about these early inhabitants 2. But it is said some were hunters and food gathers 3. They were at times called Bushmen / Hottentots 4. They were Khoisan as known to modern historians 5. These occupied the Tanzanian and Kenyan Highlands 6. The Bantu and Cushites later displace these early inhabitants 7. The Hadzapi, Sandawe and the Ndorobo are said to be some of their survivors 8. The Bantu came from Central Africa around 500AD 9. They occupied towns like Sofala, Malindi, Kilwa and Mombasa. 10. Their main occupation was farming 11. The Cushites were also among the first inhabitants 12. They migrated from North or North- eastern Ethiopia, because of the Galla 13. They occupied the Northern part of the coast and were cattle keepers 14. They are classified into the Northern Cushites and Southern Cushites 15. Examples of Cushites include the Galla, Rendile, Somalis etc 16. The Arabs and Persians came from the 7th C and took over the coast What was the way of life of these early inhabitants by 1000AD? Describe the organization of the Zenj Empire before the coming of foreigners? 1. The coast by 1000AD was inhabited by three groups of people 2. These were the Bushmen, Bantu and Cushites 3. They were organized politically, economically and socially as below 1 4. Politically, each settlement was independent and had its own chief. 5. For example, the Bantu had chiefs. 6. Chiefdoms were therefore the basic political settlements for these early people 7. -

University of South Africa Department of Development Studies

University of South Africa Department of Development Studies ACHIEVING EQUITY AND GENDER EQUALITY IN UGANDA’S TERTIARY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT By Geoffrey Odaga Student Number 46655360 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the subject of Development Studies Supervisor: Professor Esther Kibuka-Sebitosi December, 2019 i DECLARATION I declare that ACHIEVING EQUITY AND GENDER EQUALITY IN UGANDA’S TERTIARY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. DATE:16 DECEMBER 2019 SIGNATURE GEOFFREY ODAGA i DEDICATION In loving memory of Mr. Raymond Ogwal, my Dad and mentor. Your prints of love and teaching shall not be forgotten ii ABSTRACT Grounded in feminist epistemology, the study focused on the concepts of location, social position, gender and Affirmative Action to assess the social phenomenon of inequality in the distribution of public university educational opportunities in 4 regions and 112 districts of Uganda. The study used district level data of a student population of 101,504 admitted to five public universities from 2009-2017, to construct the ‘Fair Share Index’ (FSI) as a measure of higher educational inequality. Based on the FSI, the Fair Share Equity Framework of analysis was created, developed, applied and used extensively in the study, to incorporate ‘equity’ as a ‘third’ dimension in the assessment of higher educational distribution in Uganda. The Education Equity Index (EEI) was computed for each of four regions and 112 districts of the country. The EEI was defined as the difference between the Fair Share Index (FSI) or population quota and the actual proportion of the student population allocated to a region or district of the country. -

EUROPEAN ACTIVITIES in EAST AFRICA • from 1884, a Growing Number Ofeuropeans Picked Interest in East Africa. • These Came As

EUROPEAN ACTIVITIES IN EAST AFRICA From 1884, a growing number ofEuropeans picked interest in East Africa. These came as explorers, missionaries, traders and later on imperialists /colonialists. Most Europeans were either sent by their home government or by Organizations e.g. the R.G.S (Royal Geographical society), C.M.S (Church missionary society) and L.M.S (London missionary society). Others came as individuals e.g. Sir Samuel Baker and his wife and Dr. David Livingstone. Most Africans received them with open hands and offered them assistance not knowing that their activities would eventually lead to loss of African independence. EXPLORERS IN EAST AFRICA This was the 1st group of Europeans to penetrate into the interior of E.Africa. They were interested in the geography of East Africa especially the River Nile system. The explorers included;Sir Samuel Baker and his wife,Richard Burton, John Speke, Henry Morton Stanley, Dr. David Livingstone, James Grant, Jacob Erhadt e.t.c. The activities of these explorers eventually led to the colonization of East Africa. The role played by explorers in the colonization of East Africa They exaggerated the wealth of East Africa e.g. they reported about the reliable rainfall and fertile soils e.g. in Buganda which attracted more Europeans into East Africa. They provided geographical information about East Africa which attracted Europeans into East Africa e.g. John Speke discovered the source of the River Nile. The explorers destroyed the wrong impression that Africa was a ‘’ white man’s grave ‘’ which led to an influx of Europeans into East Africa. -

Urbanisation in Uganda

URBANISATION IN UGANDA Urbanisation refers to a process involving the increase in the proportion of people living in towns or cities. CATEGORIES OF URBAN CENTRES Cities such as Kampala Municipalities such as like Ntugamo, Moroto, Jinja, Mukono, Mbarara, Gulu, Arua, Hoima, Mbale, Soroti, etc. Town councils such as Luuka, Bududa, Moyo, Kayunga, Rakai, Buyende, Serere, Apac, Kole, Kamwenge, Ntoroko, Mayuge, etc. Town boards like Buwama, Namulesa, Buloba, Bukolooto, etc. SKECTH MAP OF UGANDA SHOWING MAJOR URBAN CENTRES. CURRENT STATUS OF URBAN CENTRES Urbanization in Uganda has been rapid over the previous years. It is believed that approximately 14.7% of Uganda’s population is living in urban areas today. Uganda has one of the lowest urbanisation rates in the world at 12 per cent (MFPED 2007 report). The number of urban dwellers is increasing. Urbanization in Uganda is relatively young compared to Kenya and Tanzania Uganda has one city, 30 municipalities and 174 town councils. These urban centres have grown primarily because of rural-urban migration. 21% of the total population live in urban centres.(2014 population and housing census. Urban population Trends in Uganda from 1980 to 2014 Year Population in Millions Percentage (%) 1980 0.9 6.9 1991 1.9 9.9 2002 2.9 12.3 2012 5.0 14.5 2014 7.4 Source: UBOS 2012 The State of Uganda Population Report 2012p.17 Draw a bar graph to represent the information given in the table 1 FACTORS FOR THE INCREASED URBANISATION IN UGANDA: The rapid urbanization is caused by the following factors: Physical factors The natural increase in population due to high birth rates. -

Economic and Social Development Of

THE WHITE SETTLERS IN KENYA ▪ The Europeans begun to settle in Kenya in 1896 and large number came in 1903. ▪ They mainly came from New Zealand, Britain, South Africa, Australia and Canada. ▪ Their aim was to set up plantation farms. Reasons for their coming ❖ The climatic conditions especially in Kenyan highlands were good, cool, and conducive for European settlement. ❖ Very few Africans had settled in the high lands and this is perhaps why settlers settled in such areas in large numbers. ❖ The Devonshire white paper of 1923 that gave the Kenya highlands exclusively to the whites also encouraged them to come to Kenya in large numbers. ❖ Kenya had strategic advantage i.e. it had direct access to the Indian Ocean waters and a well developed transport network. ❖ The construction of the Uganda railway line reduced transport costs and provided them with a reason to come and exploit resources in Kenya. ❖ The nomadic way of life of the some of the Kenyan tribes like the Nandi, Maasai and Kikuyu also made it easy for the settlers to obtain land. ❖ The colonial policy was clear that Kenya should be a settler colony which officially encouraged settlers to come in large numbers. ❖ Many of the governors in Kenya were too lenient and sympathetic to settler demands e.g. Sir Charles Elliot (1902-1904), Sir Donald Stewart (1904 – 1905). ❖ During the Anglo-Boer wars (1899 – 1902) in south Africa, a number of African farms were destroyed which forced many settlers to rush to East Africa expecting to find the same prospects. ❖ The earlier reports made by the explorers also encouraged the settlers to come e.g. -

Sawlog Production Grant Scheme, Phase III Newsletter

Sawlog Production Grant Scheme, Phase January - June 2019, Issue #6 III Newsletter People and Forests: Co-existing for a sustainable future ©FAO/ AnitaTibasaaga EUROPEAN UNION REPUBLIC OF UGANDA 1 Contents Foreword 1 Cluster development meeting empowers tree growers to realize high quality forest 19 International Day of Forests 2019 plantations draws attention to role of education in 2 environmental protection BOOK REVIEW: Farms, Trees and Farmers: Responses to agricultural intensification 23 Progress on implementation of the SPGS III Project 3 Forestry quick facts Women association demonstrates the 21 power of communities in forest restoration 4 Timber Market Report Highlights of training courses 6 22 Collaborative Forest Management (CFM) as an innovative approach to community forest management 8 Promoting tree planting in refugee settle- ments and host communities in Uganda 10 Non- timber forestry products have a significant place in the forestry sector 11 Transforming rural lives through forest enterprise: The story of Professor Peter Kasenene 13 Carbon financing in Uganda: An overview 15 Conservation financing: Investments that provide a positive conservation impact 16 Financing opportunities for forestry companies to enhance biodiversity conservation 18 Contributors Andrew Akasiibayo Bryony Willmott Editorial team Denis Mutaryebwa Antonio Querido Edith Nakayiza Leonidas Hitimana Josephat Kawooya Agatha Ayebazibwe Juraj Ujhazy Zainabu Kakungulu Cover photo: Women Maria Nansikombi Anita Tibasaaga harvest beans which they Miguel Leal planted in part of Professor Pauline Nantongo Peter Kasenene’s plantation Peter Bahizi in Mubende, where forest Peter Mulondo operations promote Robert Nabanyumya harmonious living with the Stella Maris Apili community Vallence Turyamureba Zainabu Kakungulu Disclaimer: This newsletter was produced with the financial support of the European Union. -

THE EARLY HISTORY of EAST AFRICAN COAST the East African Coast Stretches from Mogadishu in the North to Cape Delgado in the South

THE EARLY HISTORY OF EAST AFRICAN COAST The East African coast stretches from Mogadishu in the North to Cape Delgado in the South. The earliest people to settle at the coast where initially hunters and food gatherers .The Bantu were the first group of people to migrate to the East African coast. They came from central Africa around 500AD. They settled in towns like Mombasa, Kilwa, Sofala and Malindi. The second group of people who settled at the coast were the cushites. They migrated from North Eastern Ethiopia and occupied the northern part of the coast. The Arabs and Persians were the third group of people to migrate to the coast around 1000 A.D. They were mainly traders who crossed the Indian Ocean. However other groups like Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese, Indonesians, and Indians also found themselves coming to the coast. Their arrival was due to the booming Indian Ocean trade. THE ZENJ EMPIRE (THE LAND OF AZANIA) . The Zenj Empire was a stretch of land along the East African coast from Mogadishu up to Cape Delgado. It’ s the Arabs who named that area the Zenj Empire meaning “ The land of the black people” . The Arabs thought that it was one Empire but this was not true The coast was made up of 37 independent states. These states included; Kilwa, Sofala, Malindi, Mombasa, Pate, Scotra, Kilifi, Zanzibar, Lamu, Oja, Pemba, Gedi, Mafia, Mogadishu, e.t.c. Politically each state had its own ruler or leader. Each state was equipped with a small army. Socially the people settled in small communities and built small wattle houses.