University of South Africa Department of Development Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gathinji Silvia Nyambura.Pdf

THE ROLE OF THE MEDIA IN ATTRACTING FOREIGN INVESTORS IN KAMPALA BY GATHIN.JI SILVIA NYAMBURA Biv1C/5483/42/DF A RESEARCH REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF A BACHELOR MASS COMIYIUNICATION OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERISTY September 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Declaration ......................................................................................... ii Approval ........................................................................................... iii Dedication ........................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................ v Abstract. .............................................................................................. vi List of Abbreviations ............................................................................. vii Chapter one Introduction 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................... I I.I Background to the study ...................................................................... 2 1.2 Statement of the problem ..................................................................... 5 1.3 Purpose of the Study .......................................................................... 6 1.4 Objectives of the Study ....................................................................... 6 1.5 Research Questions ........................................................................... -

Ministry of Education,Science,Technology And

Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports Structure of Submission QUARTER 3 Performance Report Summary of Vote Performance Cumulative Progress Report for Projects and Programme Quarterly Progress Report for Projects and Programmes QUARTER 4: Workplans for Projects and Programmes Submission Checklist Page 1 Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports QUARTER 3: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution This section provides an overview of Vote expenditure (i) Snapshot of Vote Releases and Expenditures Table V1.1 below summarises cumulative releases and expenditures by the end of the quarter: Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases (i) Excluding Arrears, Taxes Budget by End by End End Mar Released Spent Spent Wage 11.218 9.015 9.015 8.648 80.4% 77.1% 95.9% Recurrent Non Wage 131.229 109.486 108.844 104.885 82.9% 79.9% 96.4% GoU 62.227 41.228 28.424 24.904 45.7% 40.0% 87.6% Development Ext Fin. 200.477 N/A 77.806 77.806 38.8% 38.8% 100.0% GoU Total 204.674 159.728 146.283 138.436 71.5% 67.6% 94.6% Total GoU+Ext Fin. (MTEF) 405.150 N/A 224.089 216.242 55.3% 53.4% 96.5% Arrears 0.642 N/A 0.642 0.553 100.0% 86.1% 86.1% (ii) Arrears and Taxes Taxes** 19.258 N/A 12.804 2.548 66.5% 13.2% 19.9% Total Budget 425.050 159.728 237.535 219.343 55.9% 51.6% 92.3% * Donor expenditure -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Makerere University Business School

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT PRIVATE ADMISSIONS, 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEAR PRIVATE THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME ON PRIVATE SCHEME BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING (MUBS) COURSE CODE ACC INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0801/525 NAMIRIMU Carolyne Mirembe 2017 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.8 2 U0083/542 ANKUNDA Crissy 2017 F U 46 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 3 U0956/649 SSALI PAUL 2017 M U 49 NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 45.4 4 U0169/626 MUHANUZI Robert 2017 M U 102 ST.ANDREA KAHWA'S COL., HOIMA 45.2 5 U0048/780 NGANDA Nasifu 2017 M U 88 MASAKA SECONDARY SCHOOL 44.5 6 U0178/502 ASHABA Lynn 2017 F U 12 CALTEC ACADEMY, MAKERERE 43.6 7 U0060/583 ATUGONZA Sharon Mwesige 2017 F U 13 TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 43.6 8 U0763/546 NYALUM Connie 2017 F U 43 BUDDO SEC. SCHOOL 43.3 9 U2546/561 PAKEE PATIENCE 2016 F U 55 PRIDE COLLEGE SCHOOL MPIGI 43.3 10 U0334/612 KYOMUGISHA Rita Mary 2011 F U 55 UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 43.1 11 U0249/532 MUGANGA Diego 2017 M U 55 ST.MARIA GORETTI S.S, KATENDE 42.1 12 U1611/629 AHUURA Baseka Patricia 2017 F U 34 OURLADY OF AFRICA SS NAMILYANGO 41.5 13 U0923/523 NABUUMA MAJOREEN 2017 F U 55 ST KIZITO HIGH SCH., NAMUGONGO 41.5 14 U2823/504 NASSIMBWA Catherine 2017 F U 55 ST. HENRY'S COLLEGE MBALWA 41.3 15 U1609/511 LUBANGAKENE Innocent 2017 M U 27 NAALYA SSS 41.3 16 U0417/569 LUBAYA Racheal 2017 F U 16 LUZIRA S.S.S. -

THE ROLE of the NATIONAL FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Nafirri) INFORMATION CENTRE in DISSEMINATING INFORMATION to RESEARCHERS and EDUCATORS

THE ROLE OF THE NATIONAL FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (NaFIRRI) INFORMATION CENTRE IN DISSEMINATING INFORMATION TO RESEARCHERS AND EDUCATORS Alice Endra [email protected] National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI) P.O Box 343, Jinja, Uganda 37th IAMSLIC Conference Zanzibar, Tanzania, October 16-20, 2011 Abstract: Information plays a vital role in the day-to-day decision making of a country’s organizations and policy makers. NaFIRRI Information Centre has played a major role in ensuring that scientists and researchers access relevant information to enable them produce quality research products. The paper discusses the role played by E-Board, a locally established network to increase access to information available within the information centre. NaFIRRI electronic board is a LAN based service that was devised to electronically facilitate information dissemination and communication within the institute. The paper looks at the different components of the E-board and the Aqualink program under the information section that was established to disseminate information on biodiversity conservation among school children and teachers. It discusses the success achieved by this program so far. Keywords: information access, information dissemination, Electronic Board, Aqualink program, biodiversity conservation, aquatic sciences. Introduction Information plays a vital role in the day-to-day decision making process of a country’s organization and policy makers. Research has shown that decision makers often adapt their decision strategies to the information environment (Payne, Bettman and Johnson, 1993). Information is needed at all levels and it is the foundation of effective planning and management as long as the information is used and disseminated. NaFIRRI Information Centre has played a major role in ensuring that scientists, technicians and other researchers from the region access relevant information to enable them produce quality research products for effective policy and decision making through its electronic information dissemination infrastructure. -

The Views of Young Farmers Club Members on Their

THE VIEWS OF YOUNG FARMERS CLUB MEMBERS ON THEIR CLUBS’ ACTIVITIES, THEIR CAREER INTERESTS, AND THEIR INTENTIONS TO PURSUE AGRICULTURE-RELATED CAREER PREPARATION AT THE POST-SECONDARY LEVEL: AN EMBEDDED CASE STUDY OF TWO SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN EASTERN UGANDA By STEPHEN CHARLES MUKEMBO Bachelor of Vocational Studies in Agriculture with Education Kyambogo University Kampala, Uganda 2005 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF AGRICULTURE May, 2013 THE VIEWS OF YOUNG FARMERS CLUB MEMBERS ON THEIR CLUBS’ ACTIVITIES, THEIR CAREER INTERESTS, AND THEIR INTENTIONS TO PURSUE AGRICULTURE-RELATED CAREER PREPARATION AT THE POST-SECONDARY LEVEL: AN EMBEDDED CASE STUDY OF TWO SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN EASTERN UGANDA Thesis Approved: Dr. Craig. M. Edwards Thesis Adviser Dr. Shida Henneberry Dr. John Ramsey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my graduate committee: Dr. M. Craig Edwards (Chair), Dr. J. W. Ramsey, and Dr. Shida Henneberry (Head of Department, International Agriculture) for their support, guidance, and encouragement throughout my research, and for contributing to my professional growth. Special thanks go to Dr. Edwards who made a tremendous sacrifice and patience in ensuring that quality work is produced. Dr. Edwards, I am very grateful for the guidance, mentorship, patience, and dedication to this research and towards my professional development. Thank you. Also Dr. Shane Robinson and Bonne Milby, thank you for your guidance and support. To my fellow graduate students Assoumane Maiga and Matofari Fred, thank you for your time, support, and encouragement. -

Kyambogo University National Merit Admission 2019-2020

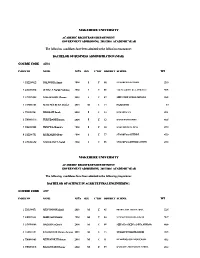

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE COURSE CODE AFD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U1223/539 BALABYE Alice Esther 2018 F U 16 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.9 2 U1223/589 NANYONJO Jovia 2018 F U 85 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.7 3 U0801/501 NAKIMBUGE Kevin 2018 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.9 4 U1688/510 TUMWESIGE Hilda Sylivia 2018 F U 34 KYADONDO SS 45.8 5 U1224/536 AKELLO Jovine 2018 F U 31 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 45.8 6 U0083/693 TUKASHABA Catherine 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 7 U1609/503 OTHIENO Tophil 2018 M U 54 NAALYA SSS 45.7 8 U0046/508 ATUHAIRE Comfort 2018 F U 123 MARYHILL HIGH SCHOOL 45.6 9 U2236/598 NABULO Gorret 2018 F U 52 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 45.6 10 U0083/541 BEINOMUGISHA Izabera 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.5 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF VOCATIONAL STUDIES IN AGRICULTURE WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE AGD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0059/548 SSEGUJJA Emmanuel 2018 M U 97 BUSOGA COLLEGE, MWIRI 33.2 2 U1343/504 AKOLEBIRUNGI Cecilia 2018 F U 30 AVE MARIA SECONDARY SCHOOL 31.7 3 U3297/619 KIYIMBA Nasser 2018 M U 51 BULOBA ROYAL COLLEGE 31.4 4 U1476/577 KIRYA Brian 2018 M U 93 RAINBOW HIGH SCHOOL, BUDAKA 31.2 5 U0077/619 KIZITO -

Volume 3, Issue 1, March 2009

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa African Centre for Statistics , p26 Africa Symposium on Statistical Development, p3 Areas Statistical Development - Selected • • SPECIAL FOCUS: SPECIAL Africa Symposium on Statistical Development 2009, Luanda, Angola African Statistical Newsletter VOLUME 3, ISSUE 1 March 2009 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: • Message from the Director, ACS 1 • Africa Symposium on Statistical Development 3 • African Statistics Day 18 • Statistical Capacity Building / Workshops 24 • Statistical Development - Selected Areas 26 • International Statistical Institute 33 • News and Events 37 Nations Unies, Commission économique pour l’Afrique Centre africain pour la statistique Symposium Africain pour le Développement de la Symposium Statistique, p3 Développement de la statistique - Sujet choisi, p26 • • ATTENTION PARTICULIÈRE: ATTENTION Symposium Africain pour le Développement de la Statistique 2009, Luanda, Angola Bulletin d’information statistique africain VOLUME 3, NUMÈRO 1 Mars 2009 DANS CE NUMÉRO: • Message du directeur du CAS 1 • Symposium Africain pour le Développement de la Statistique 3 • Journée africaine de la statistique 18 • Renforcement des capacités statistiques / Ateliers 24 • Développement de la statistique - Sujet choisi 26 • Institut international de statistique 33 • Informations et événements 37 Volume 3, Issue 1 March 2009 Volume 3, Numéro 1 Mars 2009 CONTENTS From the Director, African Centre for Statistics 1 African Centre for Statistics, UNECA Message du directeur du CAS 2 African Stakeholders Hold a -

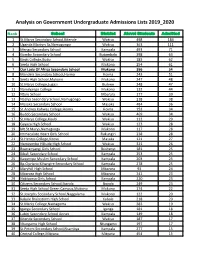

Analysis on Government Undergraduate Admissions Lists 2019 2020

Analysis on Government Undergraduate Admissions Lists 2019_2020 Rank School District Alevel Students Admitted 1 St.Marys Secondary School,Kitende Wakiso 498 184 2 Uganda Martyrs Ss,Namugongo Wakiso 363 111 3 Mengo Secondary School Kampala 493 71 4 Gombe Secondary School Butambala 398 63 5 Kings College,Budo Wakiso 183 62 6 Seeta High School Mukono 254 61 7 Our Lady Of Africa Secondary School Mukono 396 54 8 Mandela Secondary School,Hoima Hoima 243 51 9 Seeta High School,Mukono Mukono 247 48 10 St.Marys College,Lugazi Buikwe 248 47 11 Namilyango College Mukono 132 44 12 Ntare School Mbarara 177 39 13 Naalya Secondary School,Namugongo Wakiso 218 38 14 Masaka Secondary School Masaka 484 36 15 St.Andrea Kahwas College,Hoima Hoima 153 34 16 Buddo Secondary School Wakiso 469 34 17 St.Marys College,Kisubi Wakiso 112 29 18 Gayaza High School Wakiso 123 28 19 Mt.St.Marys,Namagunga Mukono 117 28 20 Immaculate Heart Girls School Rukungiri 238 28 21 St.Henrys College,Kitovu Masaka 121 27 22 Namirembe Hillside High School Wakiso 321 26 23 Bweranyangi Girls School Bushenyi 181 25 24 Kibuli Secondary School Kampala 253 25 25 Kawempe Muslim Secondary School Kampala 203 25 26 Bp.Cipriano Kihangire Secondary School Kampala 278 25 27 Maryhill High School Mbarara 93 24 28 Mbarara High School Mbarara 241 23 29 Nabisunsa Girls School Kampala 220 23 30 Citizens Secondary School,Ibanda Ibanda 249 23 31 Seeta High School Green Campus,Mukono Mukono 174 22 32 St.Josephs Secondary School,Naggalama Mukono 122 20 33 Kabale Brainstorm High School Kabale 218 20 34 St.Marks -

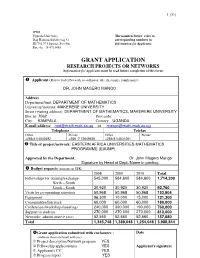

GRANT APPLICATION RESEARCH PROJECTS OR NETWORKS (Information for Applicants Must Be Read Before Completion of This Form)

1 (31) IPMS Uppsala University The numbers below refer to Dag Hammarskjölds väg 31 corresponding numbers in SE 752 37 Uppsala, Sweden Information for Applicants. Fax: 46 - 18 4713495 GRANT APPLICATION RESEARCH PROJECTS OR NETWORKS (Information for Applicants must be read before completion of this form) Applicant (Project leader/Network co-ordinator: title, first name, family name) DR. JOHN MAGERO MANGO Address Department/unit: DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS University/institute: MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Street (visiting address): DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS, MAKERERE UNIVERSITY O Box nr: 7062 Post code: City: KAMPALA Country: UGANDA E-mail address: [email protected] or [email protected] Telephone Telefax Office Private Office Private +256(41)4540692 +256 -7 72649455 +256(41)4531061 Title of project/network: EASTERN AFRICA UNIVERSITIES MATHEMATICS PROGRAMME (EAUMP) Approved by the Department : Dr. John Magero Mango Signature by Head of Dept./Name in printing Budget requests (amounts in SEK) 2008 2009 2010 Total Fellowships for training/exchange 545,000 584,600 584,600 1,714,200 North – South South – South 30,920 30,920 30,920 92,760 Visits by co-operating scientists 50,968 50,968 50,968 152,904 Equipment 96,300 10,000 15,000 121,300 Consumables/literature 60,000 60,000 60,000 180,000 Conferences/workshops/meetings 240,000 330,000 190,000 760,000 Support to students 270,000 270,000 270,000 810,000 Networks: administrative costs 52,560 52,560 52,560 157,680 Total 1,345,748 1,389,048 1,254,048 3,988,844 Grant application submitted with enclosures : Date (indicate those enclosed with yes ) Project description/Network program YES Fellowship application(s) YES Applicant's signature Applicant's CV YES Progress report YES List of publications YES 2 (31) Specification of costs in the first year (2008) Cost (SEK) Total Fellowships for training/exchange North-South Two one month research visits to Sweden 50,000 Support for 7 Ph.D. -

Resume: Ronald Othieno

Resume: Ronald Othieno Personal Information Application Title Wayleaves Officer First Name Ronald Middle Name N/A Last Name Othieno Email Address [email protected] Cell +256704122688 Nationality Uganda Gender Male Category Corporate / Organisation Middle Management Sub Category N/A Job Type Full-Time Highest Education University Total Experience 6 Year Date of Birth 03-06-1984 Work Phone N/A Home Phone +256774158026 Date you can start 01-11-2017 Driving License Yes License No. Searchable Yes I am Available Yes Address Address Address Kampala City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Institutes Institute Makerere University City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Address P.O Box 7062,Kampala-Uganda Certificate Name Bsc.Land Economics Study Area Land Economics Institute Masaka Secondary School City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Address P.O Box 212,Masaka-Uganda Certificate Name Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education Study Area Advanced Level Institute Masaka Secondary SChool City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Address P.O Box 212,Masaka-Uganda Certificate Name Uganda Certificate of Education Study Area Ordinary Level Employers Employer Employer UMEME Limited Position Assistant Wayleaves Officer Responsibilities Wayleaves acquisition for transformer injections Pay Upon Leaving 1.6 million Supervisor Muhwezi John From Date 23-08-2017 To Date 23-02-2018 Leave Reason Need for more experience and working with government organisation City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Phone +256312185185 Address Lumumba Avenue P.O Box 23841,Kampala Employer -

Makerere University Makerere University

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2015/2016 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION (MAK) COURSE CODE ADM IINNDDEEXXNN OO NNAAMMEE Al Yr S SEEXX CC''TTRRYY DDIISSTTRRIICCTT SSCCHHOOOOLL WT 11 UU11222244//881122 NNAALLWWOOGGAA AAnnnneett 2014 FF UU 6688 ST MARY'S SSSS KITENDE 5533..99 22 UU3300331/1/550088 WAFFUULLAA NNaaffuulla VVaanneessssaa 2014 FF UU 5555 THE ACADEMY ST. LAWRENCE 5500..88 33 UU2200332/2/555555 NNAAKKAAKKAANNDDEE PPhhiioonnaa 2014 FF UU 9922 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL-MUKONO 5500..55 44 UU1166009/9/556633 MMAALLEENNGGEERREERRA Danniieell 2014 MM UU 5544 NAALYA SSSSSS 5500 55 UU11110099//556611 MMBBAABBAAZZI SSaarraahh 2014 FF UU 1133 KAWANDA S. S 4499..33 66 UU00001199//661166 TTUUKKUUDDAANNEE DDoorrccuuss 2014 FF UU 1122 KIGEZI HIGH SCHOOL 4488..66 77 UU00445599//550055 TTEENNYYWWAA SShhaammiimm 2014 FF UU 1166 KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 4477..99 88 UU11222244//775511 MMUUSSEENNEERROO BBeettttyy 2014 FF UU 7777 ST MARY'S SSSS KITENDE 4477..99 99 UU22333388//667799 NNAABBUUKKEENNYYAA NNoorraahh 2014 FF UU 5555 ST.MARY'S SS KITENDE (ANNEX) 4477..99 MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2015/2016 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING COURSE CODE AGE IINNDDEEXXNN OO NNAAMMEE Al Yr S SEEXX CC''TTRRYY DDIISSTTRRIICCTT SSCCHHOOOOLL WT 11 UU11335544//997711 MMUUYYOONNJJOO RRiicchhaarrdd 2013