Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Return [Pursuant to Sub�Section(1) of Section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and Sub�Rule (1) of Rule 11Of the Companies (Management And

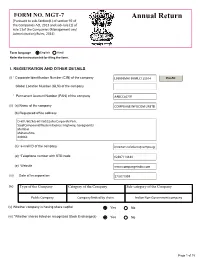

FORM NO. MGT7 Annual Return [Pursuant to subSection(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and subrule (1) of rule 11of the Companies (Management and Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company L99999MH1999PLC135914 Prefill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company AABCC4077F (ii) (a) Name of the company COMPUAGE INFOCOM LIMITED (b) Registered office address D-601/602&G-601/602,LotusCorporatePark, SteelCompound,Western Express Highway, Goregaon(E) Mumbai Maharashtra 400063 India (c) *email ID of the company investors.relations@compuage (d) *Telephone number with STD code 02267114444 (e) Website www.compuageindia.com (iii) Date of Incorporation 27/07/1999 (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Subcategory of the Company Public Company Company limited by shares Indian Non-Government company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 BSE Limited 1 2 National Stock Exchange of India Limited 1,024 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent U67190MH1999PTC118368 Prefill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent LINK INTIME INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents C-101, 1st Floor, 247 Park, Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Vikhroli (West) (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2019 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM 18/08/2020 (b) Due date of AGM 30/09/2020 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. -

THE TRUE POSTCOLONIAL a Tribute to Ananta Charan Sukla (1942-2020)

THE TRUE POSTCOLONIAL A Tribute To Ananta Charan Sukla (1942-2020) By Himansu S Mohapatra Former Professor of English, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, India n the death of Ananta Charan Sukla – he passed away in his Cuttack Iresidence on 30 September, aged 78 – Odisha lost an English Professor who was the exact opposite of the image we normally entertain of an English teacher. His choice attire was the traditional Indian dhoti and panjabi in spotless white. Sanskrit was his muse. And he worshipped at the altar of comparative literature and aesthetics. Thus Sukla was a systematic assault on the very notion of an English teacher that we in India have been taught to harbour. As such, he was far more deserving of the honour ‘postcolonial’ than many so-called Indian teachers of English who have not been able to break out of the prison of English and of the Western ideas and ideologies that are routinely conveyed through it. For what is postcoloniality if it is not an assertion of one’s independence through the pursuit of one’s local cultural originality? In Sukla’s case the latter referred to the glorious tradition of Sanskrit poetics and aesthetics. sublime para.pmd 7 16-10-2020, 12:18 Yet Sukla was an English teacher who rose through the ranks to become a Professor. He was qualified in every way for this professional role, having earned his M.A. in three subjects (English, Philosophy, and Sanskrit) and Ph.D. from Jadavpur University. It is at Sambalpur University that he spent the greater part of his professional life. -

Gabesana Prakarana Sampadana O Anubada Prabidhi = ଗବେଷଣା ପ୍ରକରଣ ସମ୍ପାଦନା ଓ ଅନୁୋଦ ପ୍ରେିଧି /Krushna Chandra Pradhan & Nirmala Kumari Raut

2005 MAIN ENTRIES 001.4 : RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Pradhan, Krushna Chandra 12042 Gabesana prakarana sampadana o anubada prabidhi = ଗବେଷଣା ପ୍ରକରଣ ସମ୍ପାଦନା ଓ ଅନୁୋଦ ପ୍ରେିଧି /Krushna Chandra Pradhan & Nirmala Kumari Raut . - 2nd Ed. - Bhubaneswar : Gyanajuga Publication , 2005 . - 242p., pbk. ; 22cm . - TRANSLATING AND INTERPRETING; EDITING AND COMPILING . - ISBN 81-87781-73-4. - 001.4 Rs.120 001.942 : UNIDENTIFIED FLYING OBJECTS,FLYING SAUCERS Mahapatra, Gokulananda 12043 Udanta thalia o ehara rahasya = ଉଡନ୍ତା ଥାଳିଆ ଓ ଏହାର ରହସୟ /Gokulananda Mahapatra . - 3rd repr. Ed. - Cuttack : Vidyapuri , 2005 . - 83p., pbk. ; 22cm . - CHILDREN'S LITERATURE:FLYING SAUCERS;CHILDREN'S LITERATURE:CURIOSITIES AND WONDERS . - 001.942 Rs.40 001.96 : SUPERSTITIONS Patnaik, Jogamaya(Dr) 12044 Samajika kusanskar durikaran = ସାମାଜିକ କୁସଂସ୍କାର ଦୂରୀକରଣ /Jogamaya Patnaik . - 4th repr. Ed. - Cuttack : Friends Publishers , 2005 . - 32p., pbk. ; 22cm . - SUPERSTITIONS-SOCIAL ASPECTS . - 001.96 Rs.15 004 : COMPUTER SCIENCE Behera, Laxmidhar 12045 Sadharana gyana computer = ସାଧାରଣ ଜ୍ଞାନ କମ୍ପୁଟର /Laxmidhar Behera . - 1st Ed. - Cuttack : Creation , 2005 . - 46p., pbk. ; 22cm . - CHILDREN'S LITERATURE:COMPUTER SCIENCE . - 004 Rs.25 Misra, Bimal 12046 E dot.com juga = ଇ ଡଟ କମ ଯୁଗ /Bimal Misra . - 1st Ed. - Cuttack : Jagannath Ratha , 2005 . - 60p., pbk. ; 22cm . - ELECTRONIC DATA PROCESSING; INTERNET . - 004 Rs.25 Mohanty, Bigyanananda 12047 Prathamika computer sikhya = ପ୍ରାଥମିକ କମ୍ପୁଟର ଶିକ୍ଷା /Bigyanananda Mohanty . - 1st Ed. - Bhubaneswar : Puja Prakashan , 2005 . - 2V(36p.,36p.),pbk.;24cm. - CHILDREN'S LITERATURE:COMPUTER LITERACY . - 004 Rs.35 004.07 : COMPUTER SCIENCE-STUDY AND TEACHING Samal, Sarbeswar 12048 New era of computer education / Sarbeswar Samal . - 1st Ed. - Cuttack : Pine Books , 2005 . - 208p., bound ; 22cm . -

Translation Today

Translation Today Editors Awadesh Kumar Mishra V. Saratchandran Nair Volume 9, Number 1, 2015 Editors Awadesh Kumar Mishra V. Saratchandran Nair Assistant Editors Geethakumary V. Abdul Halim Editorial Board Avadhesh Kumar Singh School of Translation Studies, IGNOU K.C. Baral EFLU, Shilong Campus Giridhar Rathi New Delhi Subodh Kumar Jha Magadh University Sushant Kumar Mishra CF & FS, SLL & CS, JNU A.S. Dasan University of Mysore Ch.Yashawanta Singh Manipuri University Mazhar Asif Gauhati University K.S. Rao Sahitya Akademi iii Translation Today Volume 9 No.1, 2015 Editors: Awadesh Kumar Mishra V. Saratchandran Nair © Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, 2015. This material may not be reproduced or transmitted, either in part or in full, in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from : Prof. Awadesh Kumar Mishra Director Central Institute of Indian Languages, Manasagangotri, Hunsur Road, Mysore – 570 006, INDIA Phone: 0091/ 0821 -2345006 (Director) Pabx: 0091/ 0821 -2345052 Grams: BHARATI Fax: 0091/ 0821 -2345218 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.ciil.org (Director) www.ntm.org.in To contact Head, Publications ISSN-0972-8740 Single Issue: INR 200; US $ 6: EURO 5; POUND 4 including postage (air-mail) Published by Prof. Awadesh Kumar Mishra, Director Designed By : Nandakumar L, NTM, CIIL, Mysore Printed by M.N. Chandrashekar CIIL Printing Press, Manasagangotri, Hunsur Road Mysore – 570 006, India iv In This Issue EDITORIAL 1 ARTICLES Marking Words with Part-of-Speech (POS) Tags within Text Boundary of a Corpus: the Problems, the Process and the Outcomes 5 Niladri Sekhar Dash What Unites India?: On the Role of Translation and Culture in Producing the Nation 25 Sushumna Kannan Inequality of Languages and the Question of Choice in Translation 56 Debarshi Nath Re-texting as Translation: A Study Based on Ramayana Translations in India 68 Sreedevi K. -

?` Eycvre E` 4` X ;5 D 8`Ge+ 95<

) 5*3 # 2 2 2 (*!+( ,- . +011+2 *+,-./ 0+,3.4 ,-71- + 06+( *(170'+ !*- , :(*(1(1' * + 1 ! " # ""#$!#% %#%#% -'90- ( .-*7)-'.1(8-*( +. 6-'/ )-,)-'-' 073(' #&#%%# ';(() % < ( # // 0 % ,1023,45, 6 Q R ! " #$R % .('/ +010 !" some BJP leaders”, Kumaraswamy said. MLAs, who had gone to Delhi Kumaraswamy said, “(The “I don’t know who will for the party’s National Council mid political uncertainty in Congress) MLAs have gone to benefit from such reports, but meeting in the national capital. #$ % !& %' AKarnataka over claims by Mumbai after bringing it to my in my opinion it will cause loss “BJP members have gone Congress trouble-shooter DK notice; they are in constant to the people of the State,” he for their executive meeting $!! Shivakumar that three of his touch with me,” the Chief told reporters in Mysuru. and to plan a strategy for Lok party MLAs had been whisked Minister said. ‘Operation Lotus’ is a ref- Sabha polls to win more seats. $#% $! % away by the BJP to Mumbai Not revealing their names, erence to the BJP allegedly What should I do if their meet- and are now untraceable, Chief he said, “They are my friends. luring several Opposition ing is being seen as a threat to Minister HD Kumaraswamy Those MLAs in Mumbai or 104 MLAs to defect to ensure sta- this government?” the Chief (# $ Monday said there is no ques- BJP MLAs who are in Delhi are bility of its then-Government Minister asked. tion of “instability” in the all my people, so there is no headed by B S Yeddyurappa in Kumaraswamy said he && '()*(+,- Congress-JD(S) dispensation. -

The Indian Response to Hamlet: Shakespeare’S Reception in India and a Study of Hamlet in Sanskrit Poetics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by edoc The Indian Response to Hamlet: Shakespeare’s Reception in India and a Study of Hamlet in Sanskrit Poetics Dissertation zur Erlangung des Würde einer Doktorin der Philosophie, vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Sangeeta Mohanty von Baden/ Kanton Aargau Basel 2010 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel, auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Balz Engler und Prof. Dr. Ananta Sukla Basel, den 15. Dezember 2005 Der Dekan Prof. Dr. Kaspar von Greyerz The Indian Response to Hamlet: Shakespeare’s Reception in India and a Study of Hamlet in Sanskrit Poetics Sangeeta Mohanty Dedicated to my Parents Basel, July 1st 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my sincere gratitude to several persons whose invaluable guidance, help and support have made the completion of my thesis possible. It was my guide, Prof. Dr. Balz Engler who planted the idea of choosing such a topic as I have done. I thank him profusely for supervising this study with meticulousness and critical insight, and for patiently bearing with my shortcomings. To my co-guide, Prof. Dr. Ananta Charan Sukla, I am immensely grateful for showing me the way out of the jungle and for patiently explaining to me certain critical concepts in Indian Poetics. I am highly indebted to my father, Prof. Dr. Rebati Charan Das, without whose support, I would have never reached this stage. Since it wasn’t easy to travel to India too frequently, he spared me a lot of hassle, by collecting a major part of my study material and information, from various sources and different parts of India. -

Fiction and Art

Fiction and Art i ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BLOOMSBURY A Critical Introduction to Fictionalism , Frederick Kroon Essays on the Philosophy and History of Art , Johann Joachim Winckelmann Mindful Aesthetics , Chris Danta Ten Lessons in Th eory , Calvin Th omas Th e Politics of Aesthetics , Jacques Rancière ii Fiction and Art Explorations in contemporary theory Edited by Ananta Ch. Sukla Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc iii Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Ananta Ch. Sukla and contributors, 2015 Ananta Ch. Sukla has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editor of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing- in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-47257-504-3 PB: 978-1-47257-503-6 ePDF: 978-1-47257-505-0 ePub: 978-1-47257-506-7 Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. -

Translation in Odia: a Historical Survey

Translation in Odia: A Historical Survey Aditya Kumar Panda Abstract History of translation in Odia could be studied either by surveying the major translated works in Odia chronologically or by reflecting on the development of Odia literature through translation socioculturally and politically, although both the approaches are not mutually exclusive. Translation is central to the development of Odia literature like that of any modern Indian literature. If one goes through the history of Odia literature, one can find that the quantum of Odia literature is more through translation. This essay deals with the historical account of the translation into Odia. Keyword: History, Odia, translation, adaptation, transcreation, 1. Introduction: Every history has an oral tradition of which a complete record does not exist. Whatever is recorded becomes the part of a history. A history is never a perfect history. It is biologically impossible on the part of human beings to write a perfect history which should count for each minute of the past. Therefore, history of translation is possible, if there exists written records of translation work in a language. In this historical account, “translation proper (translation of a Source Language text to a target language with fidelity to SL form and meaning)” has not only been taken into account, but also broadly interpretation, retelling, adaptation, transcreation. 1.1. Periodization: A history can be studied by dividing it according to time or place or the medium of writing. Chronologically, History of 202 Translation Today Aditya Kumar Panda Odia translation could be classified into 5 periods. They are: A. Age of Pre-Sarala and Sarala (till 15th century) B. -

2Glvkd Wr Udlvh Frdo Ur\Dow\ Uhylvlrq

!"# $%& !"#! -$"/ 16 7 2( 8(1 6/ ( ( 3 (01 1 16 2 6 3 14 ( ( 2 3 4 5 3 '%(% )* +, ' -&% ## !"#$ $%"%&%&' () that his intestines were ripped ing raids in different areas to apart and he had suffered nab the miscreants involved in he riot-hit areas of North- unimaginable brutality. arson and rioting,” Randhwa Teast Delhi, which had wit- Earlier, in Yamuna Vihar, further said. nessed the dance of death in the three to four people were seen National Security Adviser last four days, seemed to be burning vehicles on Thursday Ajit Doval had visited the returning to normalcy on around 4 am. A few kilometres Northeast Delhi’s riots affected Thursday with heavy deploy- away, a charred board of a pri- areas, a day earlier to calm sen- ment of the Delhi Police and vate school in Brijpuri read timents and also reassured Central Armed Police Forces “Welcome to a very happy people that the security forces (CAPFs) on roads. Although school.” The 52-year-old Arun were standing by them. no violence was reported on Modern Senior Secondary On Thursday, the Central Wednesday and Thursday, School looks no less than a Board of Secondary Education there was palpable sense of fear cemetery, said an official, look- (CBSE) postponed Class 10 in the areas. ing around at the damage and 12 exams scheduled on The security forces con- which he estimated to be over February 28 and 29 in the vio- ducted flag march in the areas 70 lakh. lence-hit Northeast Delhi and that saw communal violence Most shops were closed parts of East Delhi. -

Ulysses' Journey and Homer's Odyssey

Founder and Editor-in-Chief Ananta Ch. Sukla Vishvanatha Kaviraja Institute A 42, Sector-7, Markat Nagar Cuttack, Odisha, India : 753014 Email: [email protected] Tel: 91-0671-2361010 Editor Associate Editor Asunción López-Varela Richard Shusterman Faculty of Philology Center for Body, Mind and Culture University of Complutense Florida Atlantic University Madrid 28040, 777 Glades Road, Boca Raton Spain Florida - 33431-0991, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Editorial Board W.J.T. Mitchel University of Chicago David Damrosch Harvard University Alexander Huang Massachusetts Institue of Technology Garry Hagberg Bard College John Hyman Qeen’s College, Oxford Meir Sternberg Tel Aviv University Grazia Marchiano University of Siena David Fenner University of North Florida Roger Ames University of Hawaii George E. Rowe University of Oregon Sushil K. Saxena University of Delhi Susan Feagin Temple University Peter Lamarque University of York Brigitte Le Luez Dublin City University Deborah Weagel University of New Mexico John MacKinnon University of Saint Mary Osayimwense Osa Virginia State University All editorial communications, subscriptions, books for review/ notes, papers for publication are to be mailed to the editor at the address mentioned above. Editorial Assistants : Bishnu Dash ([email protected]) : Sanjaya Sarangi ([email protected]) Technical Assistant : Bijay Mohanty ([email protected]) JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND AESTHETICS Volume : 40.2 : 2017 Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics A Special Issue in The Eternal Return of Myth: Myth updating in Contemporary Literature Guest - Editors Ana González-Rivas Fernández & Antonella Lipscomb A VISHVANATHA KAVIRAJA INSTITUTE PUBLICATION www.jclaonline.org http://www.ucm.es/siim/journal-of-comparative-literature-and-aesthetics ISSN: 0252-8169 CONTENTS Felicitations on the 75th Birthday of the Founding Editor Prof. -

East Coast Railway Central Library

EAST COAST RAILWAY CENTRAL LIBRARY STOCK REPORT AS ON DATE 28-Aug-2018 ISBN No. Book Name Category Publication Author Rack/Shelf Price Stock In Hand 9788130403151 WORLDS GREAT SELECTED CHILDREN BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS PRINTLINE Rack-35 E 295 1 SHORT STORIES 9788130402864 BEST OF JOHN STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS JOHN GLASSWORTHY Rack-19 B 295 1 GLASSWORTHY 9788130402802 BEST OF HARMAN MELVELLE STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS HARAMAN MELVELLE Rack-19 B 295 1 9788130402857 BEST OF JOHN BHUCHAN STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS JOHN BUCHAN Rack-19 B 295 1 9788130403007 BEST OF SIR ARTHUR CONAN STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE Rack-19 B 295 1 DOYLE 9788130402970 BEST OF ROBERT LOUIS STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS F ROBERT LOUIS Rack-19 B 295 1 STEVENSON STEVENSON 9788130402949 BEST OF MARK TWAIN STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS MARK TWAIN Rack-19 B 295 1 9788130402840 BEST OF JANE AUSTEN STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS JANE AUSTEN Rack-19 B 295 1 9788130402635 BEST OFDANIEL DEFOE STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS DANIEL DEFOE Rack-19 B 295 1 9788130402512 BEST OF ALEXANDER DUMAS STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS ALEXANDER DUMAS Rack-19 B 295 1 9788130402529 BEST OF ANNE BRONTE STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS ANNE BRONTE Rack-19 B 295 1 9788130403083 BEST OF THE TRAGEDYKING STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS WILLIAM SHAKESPERE Rack-19 B 295 1 WILLIAM SHAKESPERE 9788130402734 BEST OF GEORGE ELIOT STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS GEORGE ELIOT Rack-19 D 295 1 9788130402628 BEST OF D.H. LAWRENCE STORY BOOKS PRINTLINE BOOKS D.H. LAWRENCE Rack-19 D 295 1 9788130402611 BEST OF F. -

History-Of-Translation-In-India.Pdf

History of Translation in India National Translation Mission Central Institute of Indian Languages Mysuru Editor Tariq Khan Assistant Editors Aditya Kumar Panda Geethakumary V. Abdul Halim History of Translation in India Editor: Tariq Khan First Published: September 2017 Bhadrapada Aashvayuja 1938 © National Traslation Mission, CIIL, Mysuru, 2017 This material may not be reproduced or transmitted, either in part or in full, in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from: Prof. D.G. Rao Director Central Institute of Indian Languages, Manasagangotri, Hunsur Road, Mysuru – 570 006, INDIA For further information contact: Head Publication For Publication orders Professor-cum-Deputy Director R. Nandeesh Head, Publications Publication Unit Contact: 0821-2345026 Contact: 0821-2345182, Email:umarani.ciil@org 09845565614 Email: [email protected], [email protected] ISBN-978-81-7343-189-0 Price: ` 400/- Published by : Prof. D.G. Rao, Director, CIIL, Mysuru Head Press & Publication : Prof. Umarani Pappuswamy Professor-cum-Deputy Director Officer-in-Charge : Sri. Aleendra Brahma, CIIL, Mysuru Supervision by : Sri. R. Nandeesh, Publication Unit Sri. M.N. Chandrashekar Layout & Design : Sri. Nandakumar L. NTM Printed at : CIIL Printing Press, Mysuru Foreword History is not only about the past but also about how the present evolves. Things are inter-related and inclusive in the world. There is no history of a subject but of subjects. History of a language is not only about the language, but also about its culture and the people who speak it. It is for this reason that a historical study is always composite in nature.