Article Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indo 91 0 1302899078 203

Andrew N. Weintraub. Dangdut Stories: A Social and Musical History of Indonesia's Most Popular Music. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010. Photographs, musical notation, glossary, bibliography, index. 258+ pp. R. Anderson Sutton At last, a book on dangdut, and an excellent one. It is hard to imagine that anyone with experience in Indonesia over the past thirty-five years could be unaware of dangdut and its pervasive presence in the Indonesian soundscape. The importance of this music was first recognized in the international scholarly world by William Frederick in his landmark article on Rhoma Irama in the pages of this journal almost thirty years ago.1 Other scholars have devoted chapters to dangdut,2 but it is only with this meticulously researched and engagingly written book-length study by Andrew Weintraub that we have the important combination of perspectives—historical, musicological, sociological, gender, and media/cultural studies—that this rich and multifaceted form of expression deserves. Weintraub offers this highly informative study under the rubric of "dangdut stories," modestly pointing to the "incomplete and selective" nature of the stories he tells. But what he has accomplished is nothing short of a tour de force, giving us a very readable history of this genre, and untangling much about its diverse origins and the multiplicity of paths it has taken into the first decade of the twenty-first century. Near the outset, following three telling vignettes of dangdut events he observed, Weintraub explains that the book is a "musical and social history of dangdut within a range of broader narratives about class, gender, ethnicity, and nation in post independence Indonesia" (p. -

Dangdut Music Affects Behavior Change at School and Adolescent Youth in Indonesia: a Literature Review Bety Agustina Rahayu*

Mini Review iMedPub Journals Health Science Journal 2018 www.imedpub.com Vol.12 No.1:552 ISSN 1791-809X DOI: 10.21767/1791-809X.1000552 Dangdut Music Affects Behavior Change at School and Adolescent Youth in Indonesia: A Literature Review Bety Agustina Rahayu* Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta, Campus FKIK UMY, Jl Lingkar Selatan, Kasihan, Bantul, DI Yogyakarta, Indonesia *Corresponding author: Bety Agustina Rahayu, Master of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta, Campus FKIK UMY, Jl Lingkar Selatan, Kasihan, Bantul, DI Yogyakarta, Indonesia, Tel: +62 274 387656; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: 18 January 2018; Accepted date: 18 February 2018; Published date: 26 February 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Rahayu BA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Citation: Rahayu BA (2018) Dangdut Music Affects Behavior Change at School and Adolescent Youth inIndonesia: A Literature Review. Health Sci J. Vol. 12 No. 1: 552. ordinary people and tends down. Sedangkan current conditions all the circles almost fall hearts with Dangdut music. Abstract Almost all electronic media like radio and television every day include Dangdut music in their show [2]. Background: Dangdut music is one type of music in Indonesia. The problems that exist today are the lyrics of Dangdut music is typically composed of drum beats, blowing Dangdut songs tend to lead to sexual and show the norm flutes, which melayu-hariu. Music has managed to hypnotize of impoliteness. -

LCGFT for Music Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Music

LCGFT for Music Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Music Nancy Lorimer, Stanford University ACIG meeting, ALA Annual, 2015 Examples Score of The Four Seasons Recording of The Four Seasons Book about The Four Seasons Music g/f terms in LCSH “Older headings” Form/genre term Subject heading Operas Opera Sacred music Church music Suites Suite (Music) “Newer headings” Genre/form term Subject heading Rock music Rock music $x History and criticism Folk songs Folk songs $x History and criticism Music g/f terms in LCSH Form/genre term Children’s songs Combined with demographic term Buddhist chants Combined with religion term Ramadan hymns Combined with event term Form/genre term $v Scores and parts $a is a genre/form or a medium of performance $v Hymns $a is a religious group $v Methods (Bluegrass) $a is an instrument; $v combines 2 g/f terms Genre/form + medium of performance in LCSH Bass clarinet music (Jazz) Concertos (Bassoon) Concertos (Bassoon, clarinet, flute, horn, oboe with band) Overtures Overtures (Flute, guitar, violin) What’s wrong with this? Variations in practice (old vs new) Genre/form in different parts of the string ($a or $v or as a qualifier) Demographic terms combined with genre/form terms Medium of performance combined with genre/form terms Endless combinations available All combinations are not provided with authority records in LCSH The Solution: LCGFT + LCMPT Collaboration between the Library of Congress and the Music Library Association, Bibliographic Control Committee (now Cataloging and Metadata Committee) Genre/Form Task Force Began in 2009 LCMPT published February, 2014 LCGFT terms published February 15, 2015 567 published in initial phase Structure Thesaurus structure Top term is “Music” All terms have at least one BT, except top term May have more than one BT (Polyhierarchy) The relationship between a term and multiple BTs is “and” not “or” (e.g., you cannot have a term whose BTs are “Cat” and “Dog”) Avoid terms that simply combine two BTs (e.g. -

Popular Music in Southeast Asia & Schulte Nordholt Popular Music in Southeast Asia Popular Music in Southeast Asia

& Schulte Nordholt Barendregt, Keppy Popular Music in Southeast Asia Banal Beats, Muted Histories Bart Barendregt, Popular Music in Southeast Asia Peter Keppy, and Henk Schulte Nordholt Popular Music in Southeast Asia Popular Music in Southeast Asia Banal Beats, Muted Histories Bart Barendregt, Peter Keppy, and Henk Schulte Nordholt AUP Cover image: Indonesian magazine Selecta, 31 March 1969 KITLV collection. By courtesy of Enteng Tanamal Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 403 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 455 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984035 nur 660 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Table of Contents Introduction 9 Muted sounds, obscured histories 10 Living the modern life 11 Four eras 13 Research project Articulating Modernity 15 1 Oriental Foxtrots and Phonographic Noise, 1910s-1940s 17 New markets 18 The rise of female stars and fandom 24 Jazz, race, and nationalism 28 Box 1.1 Phonographic noise 34 Box 1.2 Dance halls 34 Box 1.3 The modern woman 36 2 Jeans, Rock, and Electric Guitars, -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 58Th Annual Meeting Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 58th Annual Meeting Abstracts Sounding Against Nuclear Power in Post-Tsunami Japan examine the musical and cultural features that mark their music as both Marie Abe, Boston University distinctively Jewish and distinctively American. I relate this relatively new development in Jewish liturgical music to women’s entry into the cantorate, In April 2011-one month after the devastating M9.0 earthquake, tsunami, and and I argue that the opening of this clergy position and the explosion of new subsequent crises at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in northeast Japan, music for the female voice represent the choice of American Jews to engage an antinuclear demonstration took over the streets of Tokyo. The crowd was fully with their dual civic and religious identity. unprecedented in its size and diversity; its 15 000 participants-a number unseen since 1968-ranged from mothers concerned with radiation risks on Walking to Tsuglagkhang: Exploring the Function of a Tibetan their children's health to environmentalists and unemployed youths. Leading Soundscape in Northern India the protest was the raucous sound of chindon-ya, a Japanese practice of Danielle Adomaitis, independent scholar musical advertisement. Dating back to the late 1800s, chindon-ya are musical troupes that publicize an employer's business by marching through the From the main square in McLeod Ganj (upper Dharamsala, H.P., India), streets. How did this erstwhile commercial practice become a sonic marker of Temple Road leads to one main attraction: Tsuglagkhang, the home the 14th a mass social movement in spring 2011? When the public display of merriment Dalai Lama. -

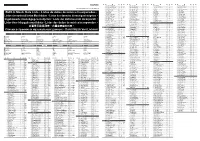

Built-In Music Data Lists • Listas De Datos De Música Incorporados

14M10APPEND-WL-1A.fm 1 ページ 2018年8月9日 木曜日 午後12時8分 269 WARM SYNTH-BRASS 1 62 35 381 SINE LEAD 80 2 494 SALUANG 77 43 608 GM TENOR SAX 66 0 270 WARM SYNTH-BRASS 2 62 38 DSP 382 VELO.SINE LEAD 80 44 495 SULING BAMBOO 2 77 42 609 GM BARITONE SAX 67 0 271 ANALOG SYNTH-BRASS 62 36 383 SYNTH SEQUENCE 80 8 496 OUD 1 105 11 610 GM OBOE 68 0 EN/ES/DE/FR/NL/IT/SV/PT/CN/TW/RU/TR 272 80'S SYNTH-BRASS 62 2 384 SEQUENCE SAW 81 15 497 OUD 2 105 42 611 GM ENGLISH HORN 69 0 273 TRANCE BRASS 63 32 385 SEQUENCE SINE 80 7 498 SAZ 15 4 612 GM BASSOON 70 0 274 TRUMPET 1 56 32 DSP 386 8BIT ARPEGGIO 1 80 9 499 KANUN 1 15 5 613 GM CLARINET 71 0 Built-in Music Data Lists • Listas de datos de música incorporados • 275 TRUMPET 2 56 2 387 8BIT ARPEGGIO 2 80 45 500 KANUN 2 15 33 614 GM PICCOLO 72 0 276 TRUMPET 3 56 36 DSP 388 8BIT WAVE 80 35 501 BOUZOUKI 105 43 615 GM FLUTE 73 0 277 MELLOW TRUMPET 56 3 389 SAW ARPEGGIO 1 81 8 502 RABAB 105 44 616 GM RECORDER 74 0 Listen der vorinstallierten Musikdaten • Listes des données de musique intégrées • 278 MUTE TRUMPET 59 1 390 SAW ARPEGGIO 2 81 9 503 KEMENCHE 110 44 617 GM PAN FLUTE 75 0 279 AMBIENT TRUMPET 56 33 DSP 391 VENT LEAD 82 32 504 NEY 1 72 10 618 GM BOTTLE BLOW 76 0 280 TROMBONE 57 32 392 CHURCH LEAD 85 32 505 NEY 2 72 41 619 GM SHAKUHACHI 77 0 Ingebouwde muziekgegevenslijsten • Liste dei dati musicali incorporati • 281 JAZZ TROMBONE 57 33 393 DOUBLE VOICE LEAD 85 34 506 ZURNA 111 9 620 GM WHISTLE 78 0 282 FRENCH HORN 60 32 394 SYNTH-VOICE LEAD 85 1 507 ARABIC ORGAN 16 7 621 GM OCARINA 79 0 283 FRENCH HORN -

Jeremy Wallach

Exploring C lass, Nation, and Xenocentrism in Indonesian Cassette Retail O utlets1 Jeremy Wallach Like their fellow scholars in the humanities and social sciences, many ethnomusicologists over the last decade have grown preoccupied with the question of how expressive forms are used to construct national cultures. Their findings have been consistent for the most part with those of researchers in other fields: namely that social agents manufacture "national" musics by strategically domesticating signs of the global modern and selectively appropriating signs of the subnational local. These two simultaneous processes result in a more or less persuasive but always unstable synthesis, the meanings of which are always subject to contestation.2 Indonesian popular music, of course, provides us with many examples of nationalized hybrid 1 1 am grateful to the Indonesian performers, producers, proprietors, music industry personnel, and fans who helped me with this project. I wish to thank in particular Ahmad Najib, Lala Hamid, Jan N. Djuhana, Edy Singh, Robin Malau, and Harry Roesli for their valuable input and assistance. I received helpful comments on earlier drafts of this essay from Matt Tomlinson, Webb Keane, Carol Muller, Greg Urban, Sandra Barnes, Sharon Wallach, and Benedict Anderson. Their suggestions have greatly improved the final result; the shortcomings that remain are entirely my own. 2 Thomas Turino, "Signs of Imagination, Identity, and Experience: A Peircean Semiotic Theory for Music," Ethnomusicology A3,2 (1999): 221-255. See also in the same issue, Kenneth Bilby, "'Roots Explosion': Indigenization and Cosmopolitanism in Contemporary Surinamese Popular Music," Ethnomusicology 43,2 (1999): 256-296 and T. M. -

Music Genre/Form Terms in LCGFT Derivative Works

Music Genre/Form Terms in LCGFT Derivative works … Adaptations Arrangements (Music) Intabulations Piano scores Simplified editions (Music) Vocal scores Excerpts Facsimiles … Illustrated works … Fingering charts … Posters Playbills (Posters) Toy and movable books … Sound books … Informational works … Fingering charts … Posters Playbills (Posters) Press releases Programs (Publications) Concert programs Dance programs Film festival programs Memorial service programs Opera programs Theater programs … Reference works Catalogs … Discographies ... Thematic catalogs (Music) … Reviews Book reviews Dance reviews Motion picture reviews Music reviews Television program reviews Theater reviews Instructional and educational works Teaching pieces (Music) Methods (Music) Studies (Music) Music Accompaniments (Music) Recorded accompaniments Karaoke Arrangements (Music) Intabulations Piano scores Simplified editions (Music) Vocal scores Art music Aʼak Aleatory music Open form music Anthems Ballades (Instrumental music) Barcaroles Cadenzas Canons (Music) Rounds (Music) Cantatas Carnatic music Ālāpa Chamber music Part songs Balletti (Part songs) Cacce (Part songs) Canti carnascialeschi Canzonets (Part songs) Ensaladas Madrigals (Music) Motets Rounds (Music) Villotte Chorale preludes Concert etudes Concertos Concerti grossi Dastgāhs Dialogues (Music) Fanfares Finales (Music) Fugues Gagaku Bugaku (Music) Saibara Hát ả đào Hát bội Heike biwa Hindustani music Dādrās Dhrupad Dhuns Gats (Music) Khayāl Honkyoku Interludes (Music) Entremés (Music) Tonadillas Kacapi-suling -

Popular Music in Southeast Asia & Schulte Nordholt Popular Music in Southeast Asia

& Schulte Nordholt Barendregt, Keppy Popular Music in Southeast Asia Banal Beats, Muted Histories Bart Barendregt, Popular Music in Southeast Asia Peter Keppy, and Henk Schulte Nordholt Popular Music in Southeast Asia Popular Music in Southeast Asia Banal Beats, Muted Histories Bart Barendregt, Peter Keppy, and Henk Schulte Nordholt AUP Cover image: Indonesian magazine Selecta, 31 March 1969 KITLV collection. By courtesy of Enteng Tanamal Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 403 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 455 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984035 nur 660 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Table of Contents Introduction 9 Muted sounds, obscured histories 10 Living the modern life 11 Four eras 13 Research project Articulating Modernity 15 1 Oriental Foxtrots and Phonographic Noise, 1910s-1940s 17 New markets 18 The rise of female stars and fandom 24 Jazz, race, and nationalism 28 Box 1.1 Phonographic noise 34 Box 1.2 Dance halls 34 Box 1.3 The modern woman 36 2 Jeans, Rock, and Electric Guitars, -

Musical Nationalisms

PART FOUR MUSICAL NATIONALISMS Jeremy Wallach - 9789004261778 Downloaded from Brill.com10/03/2021 03:09:57AM via free access Jeremy Wallach - 9789004261778 Downloaded from Brill.com10/03/2021 03:09:57AM via free access <UN> <UN> CHAPTER NINE NOTES ON DANGDUT MUSIC, POPULAR NATIONALISM, AND INDONESIAN ISLAM Jeremy Wallach I’d like to begin with a short anecdote from ‘the field’.1 One afternoon in early 2000, I was being driven to a distant East Jakarta recording studio by the chauffeur of a wealthy Indonesian music producer. During our long ride through Jakarta’s famously congested streets, a cassette containing a single dangdut song (Apa adanya [Whatever comes] by Ine Sinthya, from her forthcoming cassette) played continuously on the car stereo system. After a while, I finally asked the driver, whose name was Syaiful, if he was growing tired of hearing the same tune repeated over and over. He smiled and said no. A while later, searching for something to talk about, I asked him why he thought the lyrics of dangdut songs were often so sad. In reply, he explained: Because dangdut songs represent the innermost feelings of us all. Pop sing ers just sing for themselves, but dangdut singers represent us all, like we were the ones singing…Dangdut is broader, closer to society.2 I realized immediately that Syaiful’s response contained a succinct sum mation of a pervasive genre ideology concerning dangdut music and its place in contemporary Indonesian society. In the course of my research, 1 I am deeply grateful to the many dangdut producers, artists, critics, and fans who shared their experiences and opinions with me on this subject, especially Edy Singh, Pak Paku, Pak Hasanudin, Opie Sendewi, Lilis Karlina, Titiek Nur, Guntoro Utamadi, and Syaiful. -

The Role of Cultural Radios in Campursari Music Proliferation in East Java

ETNOSIA: JURNAL ETNOGRAFI INDONESIA Volume 5 Issue 2, DECEMBER 2020 P-ISSN: 2527-9319, E-ISSN: 2548-9747 National Accredited SINTA 2. No. 10/E/KPT/2019 A Virtual Ethnography Study: The Role of Cultural Radios in Campursari Music Proliferation in East Java Zainal Abidin Achmad1, Rachmah Ida2, Mustain3 1 Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Jawa Timur, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Campursari music is a trend on the radio and a favorite of the people campursari music; of East Java, so it is shifting towards popular culture. This study aims cultural proximity; to uncover the proliferation of campursari music and the role of cultural radio; virtual cultural radios. This qualitative research uses a virtual ethnography ethnography method, which focuses on the physical presence and virtual text together. The subjects are technology (radio and communication How to cite: technology on the internet), humans (radio listeners), physical Achmad, Z.A., Ida, R., interactions, and virtual interactions. Data collection used participant Mustain. (2020). A observation through observation and interviews offline and online in Virtual Ethnography the form of various texts, writings, images, and audiovisuals on Study: The Role of Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Youtube. The Cultural Radios in informants of this study were four cultural experts, namely: Sumadi, Campursari Music Anton Sani, Ibnu Hajar, and Juwono. This study carried out Proliferation in East Java. participatory involvement for one year in the virtual world and 30 ETNOSIA: Jurnal days living in four cities: Surabaya, Nganjuk, Banyuwangi, and Etnografi Indonesia.