UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top 100 Retailers in Asia 2020

Top 100 Retailers in Asia 2020 DEEPIKA CHANDRASEKAR AND CLARE LEE Not to be distributed without permission. The data included in this document is accurate according to Passport, Euromonitor International’s market research database, at time of publication: May 2020 Top 100 Retailers in Asia 2020 DEEPIKA CHANDRASEKAR CLARE LEE CONNECT WITH US © 2020 Euromonitor International Contents 1 Asia Pacific as an Innovation Hub 2 The Asian Landscape: Top 100 Retailers in Asia Pacific 5 Key Retailing Categories 11 Regional Spotlight: Southeast Asia 14 Country Profiles 26 Coronavirus: Outlook of Asia Pacific’s Retailing Industry on the Back of the Pandemic 28 Definitions 33 About the Authors 34 How Can Euromonitor International Help? © Euromonitor International Asia Pacific as an Innovation Hub 2019 was another year of growth for the retailing industry in Asia Pacific. What set the region apart from other markets was the proliferation of new types of brick-and-mortar and e-commerce retailing formats and new brands experimenting with various innovations in order to win the local young, and increasingly tech-savvy, population. The rapid uptake of social media in Asia Pacific, thanks to consumer segments such as millennials and Generation Z, has been a major factor in the rise of social commerce. The Asia Pacific region offers businesses great growth opportunities and profitability, due to its large working-age population, a critical mass of highly-educated people, an expanding middle class and modernisation efforts, all of which are boosting consumer expenditure and increasing demand for online retailing and e-commerce. Demographic dividend and fast-paced digital connectivity are key differentiators allowing the region to surpass other countries by paving the way for more innovative accessible services, customised products and experiences as well as creating unique digital marketplaces in the region. -

Indo 91 0 1302899078 203

Andrew N. Weintraub. Dangdut Stories: A Social and Musical History of Indonesia's Most Popular Music. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010. Photographs, musical notation, glossary, bibliography, index. 258+ pp. R. Anderson Sutton At last, a book on dangdut, and an excellent one. It is hard to imagine that anyone with experience in Indonesia over the past thirty-five years could be unaware of dangdut and its pervasive presence in the Indonesian soundscape. The importance of this music was first recognized in the international scholarly world by William Frederick in his landmark article on Rhoma Irama in the pages of this journal almost thirty years ago.1 Other scholars have devoted chapters to dangdut,2 but it is only with this meticulously researched and engagingly written book-length study by Andrew Weintraub that we have the important combination of perspectives—historical, musicological, sociological, gender, and media/cultural studies—that this rich and multifaceted form of expression deserves. Weintraub offers this highly informative study under the rubric of "dangdut stories," modestly pointing to the "incomplete and selective" nature of the stories he tells. But what he has accomplished is nothing short of a tour de force, giving us a very readable history of this genre, and untangling much about its diverse origins and the multiplicity of paths it has taken into the first decade of the twenty-first century. Near the outset, following three telling vignettes of dangdut events he observed, Weintraub explains that the book is a "musical and social history of dangdut within a range of broader narratives about class, gender, ethnicity, and nation in post independence Indonesia" (p. -

Social Responsibility As Competitive Advantage in Green Business

SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AS COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE IN GREEN BUSINESS SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AS COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AS COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE IN GREEN BUSINESS Proceeding 11th International Annual Symposium on Management Batu ‐ East Java, Indonesia, 15th‐16th March 2014 Proceeding Proceeding 11 th th management symposium on international annual international annual 11 symposium on management 11th UBAYA INTERNATIONAL ANNUAL SYM POSIUM ON MANAGEMENT Proceeding FOREWORD The 11th UBAYA International Annual Symp osium o n INSYMA has become a tradition of its own for the management Management department ofUniversitas Surabaya. For more than a decade this event has become a forum for academics and practitioners to SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITIES AS A COMPETITIVE share knowledge. Every year management department always ADVANTAGE IN GREEN BUSINESS brings the latest theme that becomes an important issue for the development of science. Editors: Werner R. Murhadi, Dr. Christina R. Honantha, S.E., M.M,CPM (Asia) This year, INSYMA raise the theme "SOCIAL Noviaty Kresna D., Dr. RESPONSIBILITIES AS A COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE Edithia Ajeng P, SE. IN GREEN BUS/NESS". This theme interesting, considering that at this time all the business need to be more accountable to Reviewers: the public and the environment. Corporate social responsibility is Candra S. Chayadi, Ph.D. (School of Business, Eastern Ill inois University) not only an obligation, otherwise it would be a distinct Dudy Anandya, Dr (Universitas Surabaya) competitive advantage for the company. Joniarto Parung, Ph.D, Prof. (Universitas Surabaya) Ning Gao, Ph.D. (M anchester Business School) Hundreds of scientific papers are sent to a conference committee, Wahyu Soedarmono, Ph.D. (Research Analyst, The World U:t ll lc, and the results of a rigorous selection of more than 100 elected. -

Labyrint Van De Verbeelding Een Onderzoek Naar De Bibliotheek Van

Labyrint van de verbeelding Een onderzoek naar de bibliotheek van Hella S. Haasse T.W.S. Steendam 10221727 MA-scriptie Redacteur/editor Universiteit van Amsterdam Begeleider: prof. dr. E.A. Kuitert Tweede lezer: prof. dr. M.T.C. Mathijsen-Verkooijen juli 2013 ‘Mijn bibliotheek is mijn beste vriend’. HELLA S. HAASSE 2 Inhoud INLEIDING 4 1: HET BELANG VAN LEZEN VOOR LEZERS EN SCHRIJVERS 7 1.1 ONDERZOEK NAAR HET BELANG VAN LEZEN 7 1.2 LEZERS OVER LEZEN EN HET VERZAMELEN VAN BOEKEN 10 1.3 SCHRIJVERS OVER LEZEN EN HET VERZAMELEN VAN BOEKEN 11 2: DE TRADITIE VAN HET INVENTARISEREN VAN SCHRIJVERSBIBLIOTHEKEN 17 2.1 DE BIBLIOTHEEK VAN S. VESTDIJK 18 2.2 DE BIBLIOTHEEK VAN GUIDO GEZELLE 20 2.3 DE BIBLIOTHEEK VAN FRANS KELLENDONK 21 2.4 DE BIBLIOTHEEK VAN LUCEBERT 22 2.5 DE BIBLIOTHEEK VAN HANS FAVEREY 23 2.6 RECENTE INVENTARISATIES: DE BIBLIOTHEKEN VAN KEES FENS, PIM FORTUYN EN HARRY MULISCH 24 3: HELLA S. HAASSE OVER LITERATUUR EN LEZEN 30 3.1 OPVOEDING EN LAGERE SCHOOL IN INDIË EN NEDERLAND (1918-1931) 31 3.2 HET LYCEUM EN LITERAIRE CLUB ELCEE IN BATAVIA (1931-1938) 44 3.3 STUDIE IN AMSTERDAM EN DE TWEEDE WERELDOORLOG (1938-1945) 50 3.4 NIEUWE NAOORLOGSE LEESERVARINGEN 52 3.5 HET BELANG VAN LEZEN IN DE JAREN ZESTIG TOT TACHTIG 56 3.6 HET BELANG VAN LEZEN IN DE JAREN NEGENTIG TOT 2011 60 4: DE BIBLIOTHEEK VAN HELLA S. HAASSE 63 4.1 VERANTWOORDING 63 4.2 ZWAARTEPUNTEN IN DE BIBLIOTHEEK 65 4.3 BEWIJZEN VAN BEZIT EN HERKOMST VAN BOEKEN 77 4.4 LEESSPOREN IN DE BIBLIOTHEEK 83 CONCLUSIE 89 BIBLIOGRAFIE 92 BIJLAGE 1: DE INVENTARIS VAN DE BIBLIOTHEEK 99 BIJLAGE 2: EEN EIGEN INVENTARIS DOOR HELLA S. -

Academic Publishing in Southeast Asia

ICAS_PIA_krant 09-07-2007 19:35 Pagina 8 8 Publishing in Asian Studies Academic Publishing in Southeast Asia by Paul H. Kratoska, per year, although Vietnam National national language. The markets for table 1 Singapore University Press University Ho Chi Minh City puts out books in English and books in vernacu- Southeast Asian universities that support academic presses [email protected] around 280 new titles annually. The lar languages are quite different, with large number of students attending uni- the latter relying heavily on a domestic Country University niversity and other academic pub- versities across the region create a large market, while books in English sell to Brunei Universiti Brunei Darussalam Ulishers are found across Asia, and potential market for academic books local English-speaking elites, and to an Indonesia Gadjah Mada University account for a significant output of books (VNU-HCM, for example, has 57,000 international audience. Catering to these Universitas Indonesia each year. Most major universities sup- full- and part-time students), but stu- two distinct markets is a major chal- Malaysia University of Malaya port a publishing programme as part of dents rely heavily on photocopying to lenge for publishers. Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia their educational function. Some of the acquire course reading materials, and Philippines University of the Philippines universities that support academic press- efforts to encourage the purchase of Although University presses receive Ateneo de Manila University es in Southeast Asia are shown in the books in connection with courses have support from their parent institutions, De La Salle University accompanying table. Other universities had only limited success. -

Dangdut Music Affects Behavior Change at School and Adolescent Youth in Indonesia: a Literature Review Bety Agustina Rahayu*

Mini Review iMedPub Journals Health Science Journal 2018 www.imedpub.com Vol.12 No.1:552 ISSN 1791-809X DOI: 10.21767/1791-809X.1000552 Dangdut Music Affects Behavior Change at School and Adolescent Youth in Indonesia: A Literature Review Bety Agustina Rahayu* Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta, Campus FKIK UMY, Jl Lingkar Selatan, Kasihan, Bantul, DI Yogyakarta, Indonesia *Corresponding author: Bety Agustina Rahayu, Master of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta, Campus FKIK UMY, Jl Lingkar Selatan, Kasihan, Bantul, DI Yogyakarta, Indonesia, Tel: +62 274 387656; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: 18 January 2018; Accepted date: 18 February 2018; Published date: 26 February 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Rahayu BA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Citation: Rahayu BA (2018) Dangdut Music Affects Behavior Change at School and Adolescent Youth inIndonesia: A Literature Review. Health Sci J. Vol. 12 No. 1: 552. ordinary people and tends down. Sedangkan current conditions all the circles almost fall hearts with Dangdut music. Abstract Almost all electronic media like radio and television every day include Dangdut music in their show [2]. Background: Dangdut music is one type of music in Indonesia. The problems that exist today are the lyrics of Dangdut music is typically composed of drum beats, blowing Dangdut songs tend to lead to sexual and show the norm flutes, which melayu-hariu. Music has managed to hypnotize of impoliteness. -

LCGFT for Music Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Music

LCGFT for Music Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Music Nancy Lorimer, Stanford University ACIG meeting, ALA Annual, 2015 Examples Score of The Four Seasons Recording of The Four Seasons Book about The Four Seasons Music g/f terms in LCSH “Older headings” Form/genre term Subject heading Operas Opera Sacred music Church music Suites Suite (Music) “Newer headings” Genre/form term Subject heading Rock music Rock music $x History and criticism Folk songs Folk songs $x History and criticism Music g/f terms in LCSH Form/genre term Children’s songs Combined with demographic term Buddhist chants Combined with religion term Ramadan hymns Combined with event term Form/genre term $v Scores and parts $a is a genre/form or a medium of performance $v Hymns $a is a religious group $v Methods (Bluegrass) $a is an instrument; $v combines 2 g/f terms Genre/form + medium of performance in LCSH Bass clarinet music (Jazz) Concertos (Bassoon) Concertos (Bassoon, clarinet, flute, horn, oboe with band) Overtures Overtures (Flute, guitar, violin) What’s wrong with this? Variations in practice (old vs new) Genre/form in different parts of the string ($a or $v or as a qualifier) Demographic terms combined with genre/form terms Medium of performance combined with genre/form terms Endless combinations available All combinations are not provided with authority records in LCSH The Solution: LCGFT + LCMPT Collaboration between the Library of Congress and the Music Library Association, Bibliographic Control Committee (now Cataloging and Metadata Committee) Genre/Form Task Force Began in 2009 LCMPT published February, 2014 LCGFT terms published February 15, 2015 567 published in initial phase Structure Thesaurus structure Top term is “Music” All terms have at least one BT, except top term May have more than one BT (Polyhierarchy) The relationship between a term and multiple BTs is “and” not “or” (e.g., you cannot have a term whose BTs are “Cat” and “Dog”) Avoid terms that simply combine two BTs (e.g. -

Popular Music in Southeast Asia & Schulte Nordholt Popular Music in Southeast Asia Popular Music in Southeast Asia

& Schulte Nordholt Barendregt, Keppy Popular Music in Southeast Asia Banal Beats, Muted Histories Bart Barendregt, Popular Music in Southeast Asia Peter Keppy, and Henk Schulte Nordholt Popular Music in Southeast Asia Popular Music in Southeast Asia Banal Beats, Muted Histories Bart Barendregt, Peter Keppy, and Henk Schulte Nordholt AUP Cover image: Indonesian magazine Selecta, 31 March 1969 KITLV collection. By courtesy of Enteng Tanamal Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 403 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 455 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984035 nur 660 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Table of Contents Introduction 9 Muted sounds, obscured histories 10 Living the modern life 11 Four eras 13 Research project Articulating Modernity 15 1 Oriental Foxtrots and Phonographic Noise, 1910s-1940s 17 New markets 18 The rise of female stars and fandom 24 Jazz, race, and nationalism 28 Box 1.1 Phonographic noise 34 Box 1.2 Dance halls 34 Box 1.3 The modern woman 36 2 Jeans, Rock, and Electric Guitars, -

Society for Ethnomusicology 58Th Annual Meeting Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 58th Annual Meeting Abstracts Sounding Against Nuclear Power in Post-Tsunami Japan examine the musical and cultural features that mark their music as both Marie Abe, Boston University distinctively Jewish and distinctively American. I relate this relatively new development in Jewish liturgical music to women’s entry into the cantorate, In April 2011-one month after the devastating M9.0 earthquake, tsunami, and and I argue that the opening of this clergy position and the explosion of new subsequent crises at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in northeast Japan, music for the female voice represent the choice of American Jews to engage an antinuclear demonstration took over the streets of Tokyo. The crowd was fully with their dual civic and religious identity. unprecedented in its size and diversity; its 15 000 participants-a number unseen since 1968-ranged from mothers concerned with radiation risks on Walking to Tsuglagkhang: Exploring the Function of a Tibetan their children's health to environmentalists and unemployed youths. Leading Soundscape in Northern India the protest was the raucous sound of chindon-ya, a Japanese practice of Danielle Adomaitis, independent scholar musical advertisement. Dating back to the late 1800s, chindon-ya are musical troupes that publicize an employer's business by marching through the From the main square in McLeod Ganj (upper Dharamsala, H.P., India), streets. How did this erstwhile commercial practice become a sonic marker of Temple Road leads to one main attraction: Tsuglagkhang, the home the 14th a mass social movement in spring 2011? When the public display of merriment Dalai Lama. -

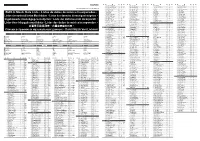

Built-In Music Data Lists • Listas De Datos De Música Incorporados

14M10APPEND-WL-1A.fm 1 ページ 2018年8月9日 木曜日 午後12時8分 269 WARM SYNTH-BRASS 1 62 35 381 SINE LEAD 80 2 494 SALUANG 77 43 608 GM TENOR SAX 66 0 270 WARM SYNTH-BRASS 2 62 38 DSP 382 VELO.SINE LEAD 80 44 495 SULING BAMBOO 2 77 42 609 GM BARITONE SAX 67 0 271 ANALOG SYNTH-BRASS 62 36 383 SYNTH SEQUENCE 80 8 496 OUD 1 105 11 610 GM OBOE 68 0 EN/ES/DE/FR/NL/IT/SV/PT/CN/TW/RU/TR 272 80'S SYNTH-BRASS 62 2 384 SEQUENCE SAW 81 15 497 OUD 2 105 42 611 GM ENGLISH HORN 69 0 273 TRANCE BRASS 63 32 385 SEQUENCE SINE 80 7 498 SAZ 15 4 612 GM BASSOON 70 0 274 TRUMPET 1 56 32 DSP 386 8BIT ARPEGGIO 1 80 9 499 KANUN 1 15 5 613 GM CLARINET 71 0 Built-in Music Data Lists • Listas de datos de música incorporados • 275 TRUMPET 2 56 2 387 8BIT ARPEGGIO 2 80 45 500 KANUN 2 15 33 614 GM PICCOLO 72 0 276 TRUMPET 3 56 36 DSP 388 8BIT WAVE 80 35 501 BOUZOUKI 105 43 615 GM FLUTE 73 0 277 MELLOW TRUMPET 56 3 389 SAW ARPEGGIO 1 81 8 502 RABAB 105 44 616 GM RECORDER 74 0 Listen der vorinstallierten Musikdaten • Listes des données de musique intégrées • 278 MUTE TRUMPET 59 1 390 SAW ARPEGGIO 2 81 9 503 KEMENCHE 110 44 617 GM PAN FLUTE 75 0 279 AMBIENT TRUMPET 56 33 DSP 391 VENT LEAD 82 32 504 NEY 1 72 10 618 GM BOTTLE BLOW 76 0 280 TROMBONE 57 32 392 CHURCH LEAD 85 32 505 NEY 2 72 41 619 GM SHAKUHACHI 77 0 Ingebouwde muziekgegevenslijsten • Liste dei dati musicali incorporati • 281 JAZZ TROMBONE 57 33 393 DOUBLE VOICE LEAD 85 34 506 ZURNA 111 9 620 GM WHISTLE 78 0 282 FRENCH HORN 60 32 394 SYNTH-VOICE LEAD 85 1 507 ARABIC ORGAN 16 7 621 GM OCARINA 79 0 283 FRENCH HORN -

Jeremy Wallach

Exploring C lass, Nation, and Xenocentrism in Indonesian Cassette Retail O utlets1 Jeremy Wallach Like their fellow scholars in the humanities and social sciences, many ethnomusicologists over the last decade have grown preoccupied with the question of how expressive forms are used to construct national cultures. Their findings have been consistent for the most part with those of researchers in other fields: namely that social agents manufacture "national" musics by strategically domesticating signs of the global modern and selectively appropriating signs of the subnational local. These two simultaneous processes result in a more or less persuasive but always unstable synthesis, the meanings of which are always subject to contestation.2 Indonesian popular music, of course, provides us with many examples of nationalized hybrid 1 1 am grateful to the Indonesian performers, producers, proprietors, music industry personnel, and fans who helped me with this project. I wish to thank in particular Ahmad Najib, Lala Hamid, Jan N. Djuhana, Edy Singh, Robin Malau, and Harry Roesli for their valuable input and assistance. I received helpful comments on earlier drafts of this essay from Matt Tomlinson, Webb Keane, Carol Muller, Greg Urban, Sandra Barnes, Sharon Wallach, and Benedict Anderson. Their suggestions have greatly improved the final result; the shortcomings that remain are entirely my own. 2 Thomas Turino, "Signs of Imagination, Identity, and Experience: A Peircean Semiotic Theory for Music," Ethnomusicology A3,2 (1999): 221-255. See also in the same issue, Kenneth Bilby, "'Roots Explosion': Indigenization and Cosmopolitanism in Contemporary Surinamese Popular Music," Ethnomusicology 43,2 (1999): 256-296 and T. M. -

Sommario Interattivo Di Pianeta Distribuzione 2010

PL Documento in versione interattiva: www.largoconsumo.info/072010/CitatiPianeta2010.pdf SOMMARIO INTERATTIVO DI PIANETA DISTRIBUZIONE 2010 Per l'acquisto del fascicolo, o di sue singole parti, rivolgersi al servizio Diffusione e Abbonamenti [email protected] Tel. 02.3271.646 Fax. 02.3271840 LE FONTI DI QUESTO PERCORSO DI LETTURA E SUGGERIMENTI PER L'APPROFONDIMENTO DEI TEMI: Pianeta Distribuzione Osservatorio D'Impresa Rapporto annuale sul grande dettaglio internazionale Leggi le case history di comunicazioni d'impresa Un’analisi ragionata delle politiche e delle strategie di sviluppo dei grandi gruppi di Aziende e organismi distributivi internazionali, food e non food e di come competono con la attivi distribuzione locale a livello di singolo Paese. Tabelle, grafici, commenti nei mercati considerati in giornalistici, interviste ai più accreditati esponenti del retail nazionale e questo internazionale, la rappresentazione fotografica delle più importanti e recenti Percorso di lettura strutture commerciali in Italia e all’estero su Pianeta Distribuzione. selezionati da Largo Consumo http://www.intranet.largoconsumo.info/intranet/Articoli/PL/VisualizzaPL.asp (1 di 16)09/11/2009 11.46.44 PL Pianeta Distribuzione, fascicolo 7/2010, n°pagina 3, lunghezza 3 pagine Tipologia: Articolo Le correnti dello scacchiere internazionale Proposte editoriali sugli La grave crisi del .... sembra essere alle spalle, le condizioni economiche restano stessi argomenti: tuttavia ancora difficili e incerte. Per il settore dei retailer, le misure di supporto e di stimolo adottate per sostenere la ripresa e il continuo impegno nell’incentivazione degli scambi commerciali promossi dai singoli Paesi hanno creato le premesse per un ritorno alla crescita. Per i retailer il ...., in termini di vendite, è stato meno negativo di molti altri ambiti.